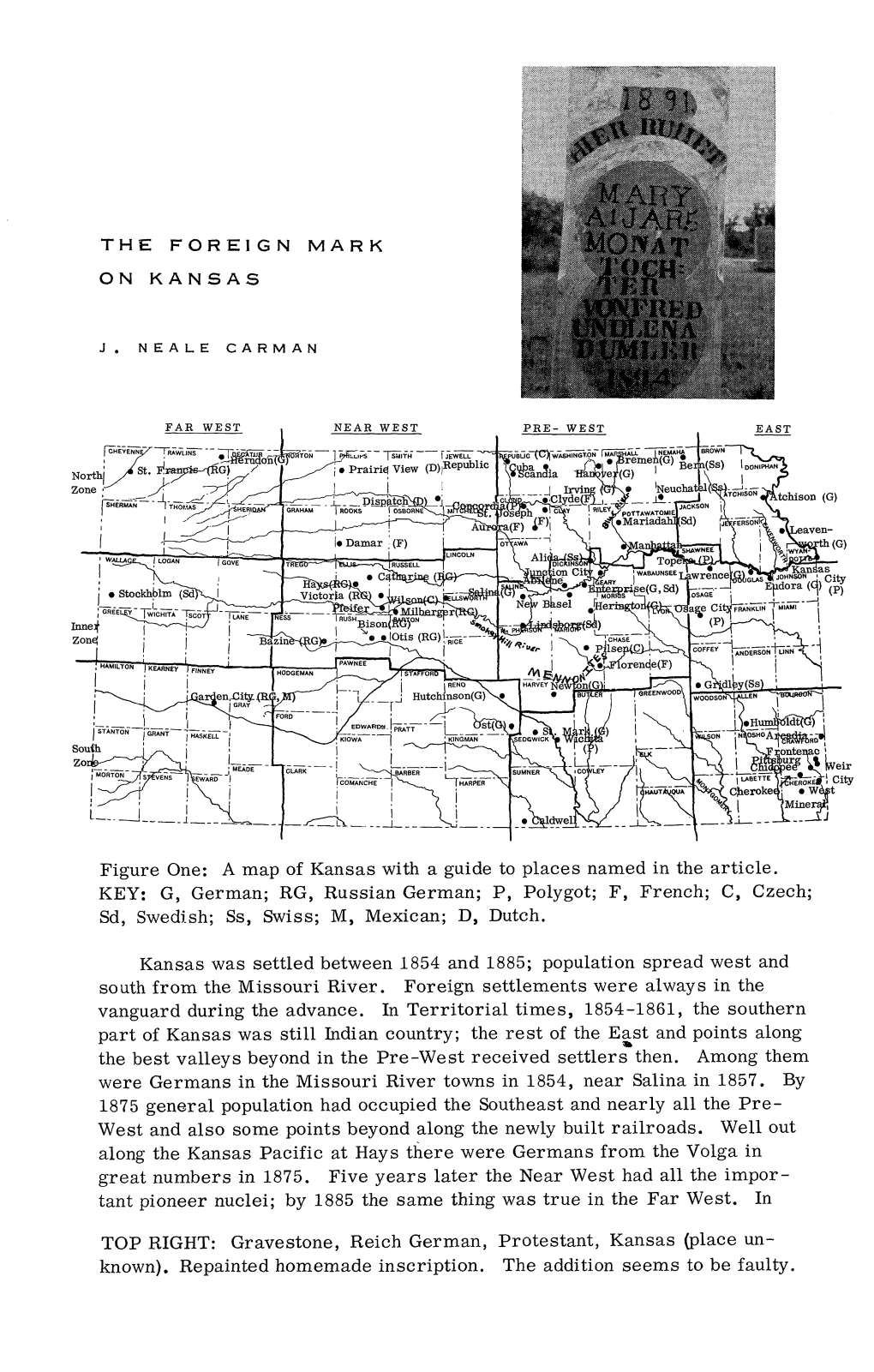

A Map of Kansas with a Guide to Places Named in the Article. KEY: G, German

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the Beginning of the Church

Excerpts from the “The Historical Road of Eastern Orthodoxy” By Alexander Schmemann Translated by Lynda W. Kesich (Please get the full version of this book at your bookstore) Content: 1. The Beginning of the Church. Acts of the Apostles. Community in Jerusalem — The First Church. Early Church Organization. Life of Christians. Break with Judaism. The Apostle Paul. The Church and the Greco-Roman World. People of the Early Church. Basis of Persecution by Rome. Blood of Martyrs. Struggle of Christianity to Keep its Own Meaning. The New Testament. Sin and Repentance in the Church. Beginnings of Theology. The Last Great Persecutions. 2. The Triumph Of Christianity. Conversion of Constantine. Relations between Church and State. The Arian Disturbance. Council of Nicaea — First Ecumenical Council. After Constantine. The Roman Position. Countermeasures in the East. End of Arianism. New Relation of Christianity to the World. The Visible Church. Rise of Monasticism. State Religion — Second Ecumenical Council. St. John Chrysostom. 3. The Age Of The Ecumenical Councils. Development of Church Regional Structure. The Byzantine Idea of Church and State Constantinople vs. Alexandria The Christological Controversy — Nestorius and Cyril. Third Ecumenical Council. The Monophysite Heresy. Council of Chalcedon (Fourth Ecumenical Council). Reaction to Chalcedon — the Road to Division. Last Dream of Rome. Justinian and the Church. Two Communities. Symphony. Reconciliation with Rome — Break with the East. Recurrence of Origenism. Fifth Ecumenical Council. Underlying Gains. Breakup of the Empire — Rise of Islam. Decay of the Universal Church Last Efforts: Monothelitism. Sixth Ecumenical Council. Changing Church Structure. Byzantine Theology. Quality of Life in the New Age. Development of the Liturgy. -

Alfred Wildfeuer Sprachenkontakt, Mehrsprachigkeit Und Sprachverlust Linguistik – Impulse & Tendenzen

Alfred Wildfeuer Sprachenkontakt, Mehrsprachigkeit und Sprachverlust Linguistik – Impulse & Tendenzen Herausgegeben von Susanne Günther, Klaus-Peter Konerding, Wolf-Andreas Liebert und Thorsten Roelcke Band 73 Alfred Wildfeuer Sprachenkontakt, Mehrsprachigkeit und Sprachverlust Deutschböhmisch-bairische Minderheitensprachen in den USA und in Neuseeland ISBN 978-3-11-055089-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-055281-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-055111-2 ISSN 1612-8702 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Einbandabbildung: Marcus Lindström/istockphoto Satz: jürgen ullrich typosatz, Nördlingen Druck und Bindung: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Gedruckt auf säurefreiem Papier Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Vorwort Die vorliegende Publikation stellt eine umfangreich überarbeitete Version meiner Habilitationsschrift dar, die im Frühjahr 2013 von der Fakultät für Sprach-, Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaften der Universität Regensburg angenommen wurde. Im Zuge der Überarbeitung wurde neueste Literatur zur Thematik berück- sichtigt. Einige Kapitel wurden gestrafft, aktuelle Forschungsergebnisse ergänzt. Die ursprünglich in den Hauptteil integierten, umfangreichen Belege zu den einzelnen -

Celebrating 50Years of the Prisoner

THE MAGAZINE BEYOND YOUR IMAGINATION www.infinitymagazine.co.uk THE MAGAZINE BEYOND YOUR IMAGINATION 6 DOUBLE-SIDED POSTER INSIDE! “I AM NOT A NUMBER!” CELEBRATING 50 YEARS PLUS: OF THE PRISONER • CHRISTY MARIE - COSPLAY QUEEN • SPACECRAFT KITS • IAIN M. BANKS • THE VALLEY OF GWANGI • NEWS • SATURDAY MORNING SUPERHEROES • CHILDREN’S FILM FOUNDATION AND MUCH, MUCH MORE… FUTURE SHOCK! THE HISTORY OF 2000 AD AN ARRESTING CONCEPT - TAKE A TRIP IN ROBOCOP THE TIME TUNNEL WRITER INFINITY ISSUE 6 - £3.99 06 THE MAGAZINE BEYOND YOUR IMAGINATION www.infinitymagazine.co.uk 6 THE MAGAZINE BEYOND YOUR IMAGINATION DOUBLE-SIDED POSTER INSIDE! 8 14 “I AM NOT A 38 NUMBER!”50 YEARS CELEBRATING OF THE PRISONER • SPACECRAFT KITS PLUS: • NEWS • CHRISTY MARIE• THE - COSPLAY VALLEY QUEEN OF GWANGI• CHILDREN’S • IAIN M. BANKS • SATURDAY MORNING SUPERHEROES FILM FOUNDATION AND MUCH, MUCH MORE… FUTURE SHOCK! AN ARRESTING THE HISTORY OF CONCEPT - 2000 AD ROBOCOP WRITER TAKE A TRIP IN THE TIME TUNNEL INFINITY ISSUE 6 - £3.99 Prisoner cover art by Mark Maddox (www.maddoxplanet.com) 19 44 08: CONFESSIONS OF A CONVENTION QUEEN Pat Jankiewicz discovers how Star Wars FanGirl Christy Marie became a media phenomenon! 14: SATURDAY MORNING SUPER-HEROES Jon Abbott looks at Hanna-Barbera’s Super TV Heroes line of animated adventurers. 19: UNLOCKING THE PRISONER Don’t miss this amazing 11-page special feature on Patrick McGoohan’s cult favourite from the 1960s. 38: MODEL BEHAVIOUR Sci-fi & Fantasy Modeller’s Andy Pearson indulges his weakness for spacecraft kits… 40 40: FUTURE SHOCK! John Martin talks to Paul Goodwin, director of an acclaimed documentary on the history of 2000 AD. -

The Political Economy of Stalinism Evidence from the Soviet Secret Archives

P1: FCH/FFX P2: FCH/FFX QC: FCH/FFX T1: FCH CB575-FM CB575-Gregory-v1 July 31, 2003 9:53 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: FCH/FFX P2: FCH/FFX QC: FCH/FFX T1: FCH CB575-FM CB575-Gregory-v1 July 31, 2003 9:53 The Political Economy of Stalinism Evidence from the Soviet Secret Archives This book uses the formerly secret Soviet State and Communist Party archives to describe the creation and operations of the Soviet administrative-command system. It concludes that the system failed not because of the “jockey” (i.e., Stalin and later leaders) but because of the “horse” (the economic system). Although Stalin was the system’s prime architect, the system was managed by thousands of “Stalins” in a nested dictatorship. The core values of the Bolshevik Party dictated the choice of the administrative-command system, and the system dictated the po- litical victory of a Stalin-like figure. This study pinpoints the reasons for the failure of the system – poor planning, unreliable supplies, the preferential treatment of indigenous enterprises, the lack of knowledge of planners, etc. – but also focuses on the basic principal–agent conflict between planners and producers, which created a sixty-year reform stalemate. Once Gorbachev gave enterprises their freedom, the system had no direction from either a plan or a market, and the system im- ploded. The Soviet administrative-command system was arguably the most significant human experiment of the twentieth century. If repeated today, its basic contradictions and inherent flaws would remain, and its economic results would again prove inferior. -

AK2117-J4-11-AAM-001-Jpeg.Pdf

h OR WARD TO if B # % strategy, tactics and programme of the af rican national congress SOUTH AFRICA ? oku™ ^ t''"w ere a W r ^ f # * ^ ? c.n,ty that m.s document is a true reproduction/copy of the vsn die oorspronklike wat deur my persoorlik ht-vr-in *** «•» -»»■ >- »y dat. volgcr>a my waamcminCs. dlo corscfonViik.. r - -n lions, the original has „ « t ^ n altered in ^ ‘ * wyse gevvyslg is nie. /tc+~sJ- 198S - 0 7 ~ f } Handtekoniog/SlgfiEiure FORWARD TO FREEDOM Documents on the National Policies of the African National Congress of South Africa Ck 50ft: f GOHurT*<;n( *r' 1 cfertsly that thi& document is a true tproduciionJcopy o' the ven die oorspronklike wat deur my pp'foor! * i;*t ,s cn original whicn v.as examined by rr^ ancJth^t.?--: ■■ r : , dat, volocns my woarnsmings. d!o co r5,>:;/*►■ ;• c;; ©nije ' tions, trie origir.a' has net been aiierco :n z n / r:...\.ior.- f I i 4 i \ CONTENTS i Strategy and Tactics of the ANC: Revolutionary Programme of the ANC: An analysis of the Freedom Charter in the light of the 'p>»*cgt^orined phase of our struggle 19 The Freedom Charter: Full text os odopted on June 26. 1955 ot Kliptown, Johannesburg 29 fcx fsn:lisee< ty-yo-e cz<->r*rt .n ah--.- ! cr.riKy tr.ai Ifws document is 2 iruc rcp'ccyctic-'.'c-;:;, _■ 'no vsn d!a oorspronklike wat ciajr fny pers^j i k t'.' 'j -"-- 1: ' ori£’nsJ wtuch « w examines by ms t" rt. t *:*t. -

Proquest Dissertations

Finnish art song for the American singer Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Tuomi, Scott Lawrence Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 10:24:07 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289889 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMl films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMl a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing In this copy for an additional charge. -

PERSA Working Paper No. 20

Collectivization, Accumulation, and Power Command: The Political Economy of Stalin’s Dictatorship. An Archival Study, Chapter 2 Paul R. Gregory University of Houston [email protected] PERSA Working Paper No. 20 Political Economy Department of Economics Research in Soviet Archives Version: 26 September 2002 Chapter 2 The Inevitability of the “Great Break-Through” 26 September 2002 1 CHAPTER 2 COLLECTIVIZATION, ACCUMULATION, AND POWER Chapter Prologue “My Grandfather grew up in a village, where he cultivated the land with his brother and their children. His neighbor, Petya, was a neer-do-well, who slept on the porch of his ramshackle hut and spent his evenings drinking and beating his miserable wife. He would watch in disdain as we sweated in the hot sun building a new barn or brought home a new cow. During hard times, Petya would appear at our door asking for a handout . In 1929, Petya appeared at my Grandfather’s door accompanied by a handful of thugs, sporting a military uniform and cap bearing a red star and declared: ‘In the name of Soviet power, I order you to hand over all your property and land to the collective.’ This is why my Grandfather hated Communism and Soviet power all his life.” Story told to the author in Moscow by a seventy-five year old Russian. Command describes how and why a small group of socialist revolutionaries, led by one of history’s worst tyrants, Josef Stalin, created the world’s first administrative- command economy. The story is told from the records of the formerly secret Soviet archives from the same documents these “founders” used more than a half-century earlier. -

The Political Economy of Stalinism Evidence from the Soviet Secret Archives

P1: FCH/FFX P2: FCH/FFX QC: FCH/FFX T1: FCH CB575-FM CB575-Gregory-v1 July 31, 2003 9:53 The Political Economy of Stalinism Evidence from the Soviet Secret Archives This book uses the formerly secret Soviet State and Communist Party archives to describe the creation and operations of the Soviet administrative-command system. It concludes that the system failed not because of the “jockey” (i.e., Stalin and later leaders) but because of the “horse” (the economic system). Although Stalin was the system’s prime architect, the system was managed by thousands of “Stalins” in a nested dictatorship. The core values of the Bolshevik Party dictated the choice of the administrative-command system, and the system dictated the po- litical victory of a Stalin-like figure. This study pinpoints the reasons for the failure of the system – poor planning, unreliable supplies, the preferential treatment of indigenous enterprises, the lack of knowledge of planners, etc. – but also focuses on the basic principal–agent conflict between planners and producers, which created a sixty-year reform stalemate. Once Gorbachev gave enterprises their freedom, the system had no direction from either a plan or a market, and the system im- ploded. The Soviet administrative-command system was arguably the most significant human experiment of the twentieth century. If repeated today, its basic contradictions and inherent flaws would remain, and its economic results would again prove inferior. Paul R. Gregory is Cullen Professor of Economics at the University of Houston and currently serves as a Research Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. -

The Tapestry of Russian Christianity: Studies in History and Culture

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass EKU Faculty and Staff Books Gallery Faculty and Staff Scholarship Collection 2016 Tapestry of Russian Christianity: Studies in History and Culture Jennifer B. Spock, Editor Eastern Kentucy University Nickolas Lupinin, Editor Franklin Pierce College, Emeritus Donald Ostrowski, Editor LM Program at the Division of Continuing Education, Harvard University Extension School Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/fs_books Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Spock, Editor, Jennifer B.; Lupinin, Editor, Nickolas; and Ostrowski, Editor, Donald, "Tapestry of Russian Christianity: Studies in History and Culture" (2016). EKU Faculty and Staff Books Gallery. 9. https://encompass.eku.edu/fs_books/9 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Staff Scholarship Collection at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in EKU Faculty and Staff Books Gallery by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Department of Slavic and East European Languages and Cultures Resource Center for Medieval Slavic Studies The Tapestry of Russian Christianity The Tapestry Editors: Nickolas Lupinin Donald Ostrowski Jennifer B. Spock Ohio Slavic Papers Vol. 10 Eastern Christian Studies Vol. 2 The Tapestry of Russian Christianity: OSP10/ Studies in History and Culture ECS2 ISSN 1932-7617 The Ohio State University Department of Slavic and East European Languages and Cultures & Resource Center for Medieval Slavic Studies Ohio Slavic Papers, vol. 10 rj Eastern Christian Studies, vol. 2 THE TAPESTRY OF RUSSIAN CHRISTIANITY Studies in History and Culture Edited by Nickolas Lupinin, Donald Ostrowski and Jennifer B.