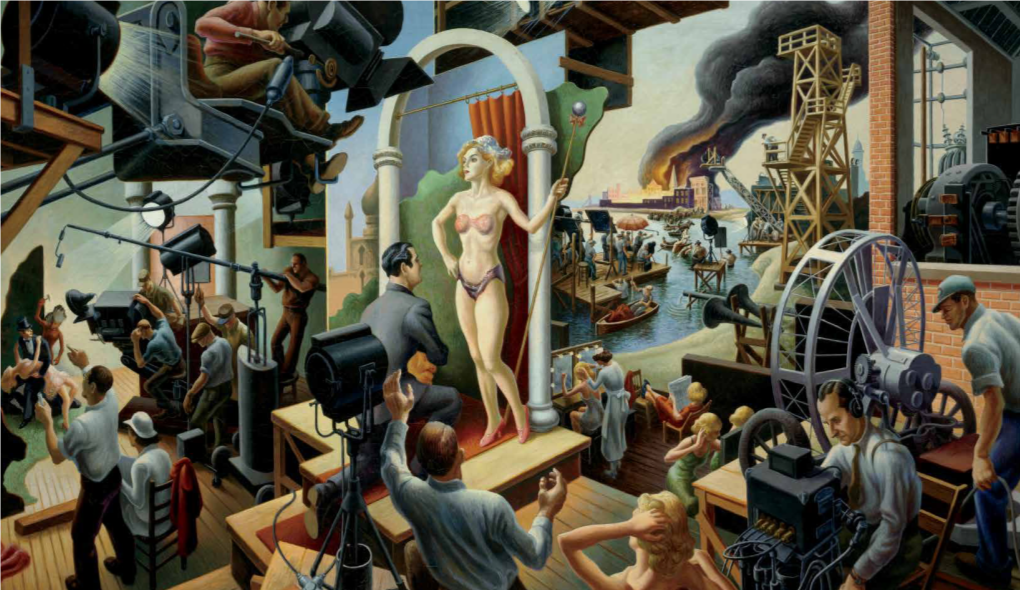

Mining the Dream Factory: Thomas Hart Benton, American Artists, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BULLETIN PRESIDENT TREASURER EDITOR John Bachochin Loren Moore Mike Prero 15731 S

BULLETIN PRESIDENT TREASURER EDITOR John Bachochin Loren Moore Mike Prero 15731 S. 4210 Rd., POB 1181 12659 Eckard Way Claremore, OK 74017 Roseville, CA 95678 Auburn,CA 95603 918-342-0710 916-783-6822 530-906-4705 No. 355 August 2014 by Mike Prero The hobby has produced a lot of covers over the last 75 years, and, perhaps not surprisingly, its share of bloopers...at the very least! To be fair, the manufacturers were responsible for most of them, but the designers had their share. In any event, we have a wide variety of offerings here—I‘ve left out all the miscuts and other production errors; these are all ‗somebody goofed‘ errors... No. 355 SIERRA-DIABLO BULLETIN-August 2014 Page 2 No. 355 SIERRA-DIABLO BULLETIN-August 2014 Page 3 In case you couldn’t find some of the errors... 1st page, 3rd cover: 7th Anniversary 2nd page, 1st cover: Schaumburg 2nd page, 2nd cover: wrong dates 2nd page, 3rd cover: Hotel 2nd page, 4th cover: congratulates 2nd page, 5th cover: Bitter 2nd page,6th cover: 1996 > 1997 2nd page, 7th cover: Congratulations 3rd page, 1st cover: it‘s > its 3rd page, 2nd cover: it‘s > its and Gouverneurs 3rd page, 3rd cover: Bob Lincoln 3rd Page, 4th cover: Heskett 3rd page, 5th cover: Cindy No. 355 SIERRA-DIABLO BULLETIN-August 2014 Page 4 Great Ships of the Seas: The Italia She began her life as the Swedish-American Line‘s Kungsholm, built in 1928. Even then,, she was a noted transatlantic liner. Later, beginning in the early thirties, she also developed a good reputation on luxury long-distance cruises. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

Paintings by John W. Alexander ; Sculpture by Chester Beach

SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO, DECEMBER 12 1916 TO JANUARY 2, 1917 PAINTINGS BY JOHN W. ALEXANDER SCULPTURE BY CHESTER BEACH PAINTINGS BY CALIFORNIA ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY WILSON IRVINE PAINTINGS BY EDWARD W. REDFIELD PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES BY MAURICE STERNE 0 SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS OF WORK BY THE FOLLOWING ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY JOHN W. ALEXANDER SCULPTURE BY CHESTER BEACH PAINTINGS BY CALIFORNIA ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY WILSON IRVINE PAINTINGS BY EDWARD W. REDFIELD PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES BY MAURICE STERNE THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO DEC. 12, 1916 TO JAN. 2, 1917 PAINTINGS BY JOHN WHITE ALEXANDER OHN vV. ALEXANDER. Born, Pittsburgh, J Pennsylvania, 1856. Died, New York, May 31, 1915. Studied at the Royal Academy, Munich, and with Frank Duveneck. Societaire of Societe Nationale des Beaux Arts, Paris; Member of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, London; Societe Nouvelle, Paris ; Societaire of the Royal Society of Fine Arts, Brussels; President of the National Academy of Design, New York; President of the Natiomrl Academy Association; President of the National Society of Mural Painters, New York; Ex- President of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, New York; American Academy of Arts and Letters; Vice-President of the National Fine Arts Federation, Washington, D. C.; Member of the Architectural League, Fine Arts Federation and Fine Arts Society, New York; Honorary Member of the Secession Society, Munich, and of the Secession Society, Vienna; Hon- orary Member of the Royal Society of British Artists, of the American Institute of Architects and of the New York Society of Illustrators; President of the School Art League, New York; Trustee of the New York Public Library; Ex-President of the MacDowell Club, New York; Trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Trustee of the American Academy in Rome; Chevalier of the Legion of Honor, France; Honorary Degree of Master of Arts, Princeton University, 1892, and of Doctor of Literature, Princeton, 1909. -

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

Milch Galleries

THE MILCH GALLERIES YORK THE MILCH GALLERIES IMPORTANT WORKS IN PAINTINGS AND SCULPTURE BY LEADING AMERICAN ARTISTS 108 WEST 57TH STREET NEW YORK CITY Edition limited to One Thousand copies This copy is No 1 his Booklet is the second of a series we have published which deal only with a selected few of the many prominent American artists whose work is always on view in our Galleries. MILCH BUILDING I08 WEST 57TH STREET FOREWORD This little booklet, similar in character to the one we pub lished last year, deals with another group of painters and sculp tors, the excellence of whose work has placed them m the front rank of contemporary American art. They represent differen tendencies, every one of them accentuating some particular point of view and trying to find a personal expression for personal emotions. Emile Zola's definition of art as "nature seen through a temperament" may not be a complete and final answer to the age-old question "What is art?»-still it is one of the best definitions so far advanced. After all, the enchantment of art is, to a large extent, synonymous with the magnetism and charm of personality, and those who adorn their homes with paintings, etchings and sculptures of quality do more than beautify heir dwelling places. They surround themselves with manifestation of creative minds, with clarified and visualized emotions that tend to lift human life to a higher plane. _ Development of love for the beautiful enriches the resources of happiness of the individual. And the welfare of nations is built on no stronger foundation than on the happiness of its individual members. -

8 Redefining Zorro: Hispanicising the Swashbuckling Hero

Redefining Zorro: Hispanicising the Swashbuckling Hero Victoria Kearley Introduction Such did the theatrical trailer for The Mask of Zorro (Campbell, 1998) proclaim of Antonio Banderas’s performance as the masked adventurer, promising the viewer a sexier and more daring vision of Zorro than they had ever seen before. This paper considers this new image of Zorro and the way in which an iconic figure of modern popular culture was redefined through the performance of Banderas, and the influence of his contemporary star persona, as he became the first Hispanic actor ever to play Zorro in a major Hollywood production. It is my argument that Banderas’s Zorro, transformed from bandit Alejandro Murrieta into the masked hero over the course of the film’s narrative, is necessarily altered from previous incarnations in line with existing Hollywood images of Hispanic masculinity when he is played by a Hispanic actor. I will begin with a short introduction to the screen history of Zorro as a character and outline the action- adventure hero archetype of which he is a prime example. The main body of my argument is organised around a discussion of the employment of three of Hollywood’s most prevalent and enduring Hispanic male types, as defined by Latino film scholar, Charles Ramirez Berg, before concluding with a consideration of how these ultimately serve to redefine the character. Who is Zorro? Zorro was originally created by pulp fiction writer, Johnston McCulley, in 1919 and first immortalised on screen by Douglas Fairbanks in The Mark of Zorro (Niblo, 1920) just a year later. -

DINNERS ENROLL TOM SAWYER.’ at 2:40

1 11 T 1 Another Film for Film Fans to Suggest Gordon tried out in the drama, "Ch.!« There Is dren of Darkness.” It was thought No ‘Cimarron’ Team. Janet’s Next Role. in Theaters This Week the play would be a failure, so they Photoplays Washington IRENE DUNNE and ^ Wesley Ruggles, of the Nation will * fyJOVIE-GOERS prepared to abandon It. A new man- who as star and director made be asked to suggest the sort of agement took over the property, as- WEEK OP JUNE 12 SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY cinematic history in 1931 In “Cimar- Stopping picture In which little Janet Kay signed Basil Sydney and Mary Ellis "Bit Town Olrl." "Manneouln." "Manneouln." are to be "Naughty Marietta" "Haughty Marietta" "Thank You. Ur. ron," reunited as star and Chapman. 4-year-old star dis- to the leads and Academy "alfm*83ifl£L'‘ Jon Hall in Will Rogers in Will Rosen in and ‘•The Shadow of and "The Shadow of Moto.” and "Ride. recently they scored a Broad- " director of a Paramount to Sth »nd O Sts. B.E, "The Hu-rlcane." "The Hurricane." _"David Harum "David Harum."_Silk Lennox."_ Silk Lennox." Ranter. Ride." picture covered by a Warner scout, should be way hit. This Lad in } into in the Rudy Vailee Rudy Valle? in Rudy Vallee in Myrna Loy. Clark Oa- Myrna Loy. Clark Oa- Loretta Yoon* in go production early fall. next seen on the screen. Miss So It Is at this time of Ambassador •■Sm* "Gold Diggers in "Gold Diggers in "Oold in ble and ble Chap- only yea# DuE*niBin Diggers Spencer Tracy and Spencer Tracy "Four Men and a The announcement was made after man the 18th «nd OolumblA Rd. -

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881 - 1973)

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881 - 1973) Pablo Picasso is considered to be the greatest artist of the 20th century, the Grand Master primo assoluto of Modernism, and a singular force whose work and discoveries in the realm of the visual have informed and influenced nearly every artist of the 20th century. It has often been said that an artist of Picasso’s genius only comes along every 500 years, and that he is the only artist of our time who stands up to comparison with da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael – the grand triumvirate of the Italian Renaissance. Given Picasso’s forays into Symbolism, Primitivism, neo-Classicism, Surrealism, sculpture, collage, found-object art, printmaking, and post-WWII contemporary art, art history generally regards his pioneering of Cubism to have been his landmark achievement in visual phenomenology. With Cubism, we have, for the first time, pictorial art on a two-dimensional surface (paper or canvas) which obtains to the fourth dimension – namely the passage of Time emanating from a pictorial art. If Picasso is the ‘big man on campus’ of 20th century Modernism, it’s because his analysis of subjects like figures and portraits could be ‘shattered’ cubistically and re-arranged into ‘facets’ that visually revolved around themselves, giving the viewer the experience of seeing a painting in the round – all 360º – as if a flat work of art were a sculpture, around which one walks to see its every side. Inherent in sculpture, it was miraculous at the time that Picasso could create this same in-the-round effect in painting and drawing, a revolution in visual arts and optics. -

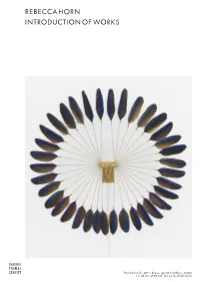

Rebecca Horn Introduction of Works

REBECCA HORN INTRODUCTION OF WORKS • Parrot Circle, 2011, brass, parrot feathers, motor t = 28 cm, Ø 67 cm | d = 11 in, Ø 26 1/3 in Since the early 1970s, Rebecca Horn (born 1944 in Michelstadt, Germany) has developed an autonomous, internationally renowned position beyond all conceptual, minimalist trends. Her work ranges from sculptural en- vironments, installations and drawings to video and performance and manifests abundance, theatricality, sensuality, poetry, feminism and body art. While she mainly explored the relationship between body and space in her early performances, that she explored the relationship between body and space, the human body was replaced by kinetic sculptures in her later work. The element of physical danger is a lasting topic that pervades the artist’s entire oeuvre. Thus, her Peacock Machine—the artist’s contribu- tion to documenta 7 in 1982—has been called a martial work of art. The monumental wheel expands slowly, but instead of feathers, its metal keels are adorned with weapon-like arrowheads. Having studied in Hamburg and London, Rebecca Horn herself taught at the University of the Arts in Berlin for almost two decades beginning in 1989. In 1972 she was the youngest artist to be invited by curator Harald Szeemann to present her work in documenta 5. Her work was later also included in documenta 6 (1977), 7 (1982) and 9 (1992) as well as in the Venice Biennale (1980; 1986; 1997), the Sydney Biennale (1982; 1988) and as part of Skulptur Projekte Münster (1997). Throughout her career she has received numerous awards, including Kunstpreis der Böttcherstraße (1979), Arnold-Bode-Preis (1986), Carnegie Prize (1988), Kaiserring der Stadt Goslar (1992), ZKM Karlsruhe Medienkunstpreis (1992), Praemium Imperiale Tokyo (2010), Pour le Mérite for Sciences and the Arts (2016) and, most recently, the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize (2017). -

Darryl F. Zanuck's <Em>Brigham Young</Em>: a Film in Context

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 29 Issue 1 Article 2 1-1-1989 Darryl F. Zanuck's Brigham Young: A Film in Context James V. D'Arc Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation D'Arc, James V. (1989) "Darryl F. Zanuck's Brigham Young: A Film in Context," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 29 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol29/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. D'Arc: Darryl F. Zanuck's <em>Brigham Young</em>: A Film in Context darryl F zanucks brigham young A film in context james V darc when darryl F zanucks brigham young was first released in 1940 president heber J grant of the church of jesus christ of latter day saints praised the motion picture as a friendmakerfriendmaker 1 I1 the prestigious hollywood studio twentieth century fox had spent more money on it than most motion pictures made up to that time its simultaneous premiere in seven theaters in one city still a world record was preceded by a grand parade down salt lake citescitys main street businesses closed for the event and the mayor proclaimed it brigham young day 2 not all reactions to the film however have been so favorable A prominent biographer of brigham young called the movie merely an interesting romance when a more authentic -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES and CLASSICS June 24 - September 30, 1994

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release May 1994 MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES AND CLASSICS June 24 - September 30, 1994 A retrospective celebrating the seventieth anniversary of Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer, the legendary Hollywood studio that defined screen glamour and elegance for the world, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on June 24, 1994. MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES AND CLASSICS comprises 112 feature films produced by MGM from the 1920s to the present, including musicals, thrillers, comedies, and melodramas. On view through September 30, the exhibition highlights a number of classics, as well as lesser-known films by directors who deserve wider recognition. MGM's films are distinguished by a high artistic level, with a consistent polish and technical virtuosity unseen anywhere, and by a roster of the most famous stars in the world -- Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, Judy Garland, Greta Garbo, and Spencer Tracy. MGM also had under contract some of Hollywood's most talented directors, including Clarence Brown, George Cukor, Vincente Minnelli, and King Vidor, as well as outstanding cinematographers, production designers, costume designers, and editors. Exhibition highlights include Erich von Stroheim's Greed (1925), Victor Fleming's Gone Hith the Hind and The Wizard of Oz (both 1939), Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Ridley Scott's Thelma & Louise (1991). Less familiar titles are Monta Bell's Pretty Ladies and Lights of Old Broadway (both 1925), Rex Ingram's The Garden of Allah (1927) and The Prisoner - more - 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART 2 of Zenda (1929), Fred Zinnemann's Eyes in the Night (1942) and Act of Violence (1949), and Anthony Mann's Border Incident (1949) and The Naked Spur (1953).