Toronto's Edwardian Skyscraper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World's Columbian Exposition: Idea, Experience, Aftermath

The World's Columbian Exposition: Idea, Experience, Aftermath Julie Kirsten Rose Morgan Hill, California B.A., San Jose State University, 1993 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English University of Virginia August 1996 L IV\CLslerI s E~A-3 \ ~ \qa,(c, . R_to{ r~ 1 COLOPHON AND DEDICATION This thesis was conceived and produced as a hypertextual project; this print version exists solely to complete the request and requirements of department of Graduate Arts and Sciences. To experience this work as it was intended, please point your World Wide Web browser to: http:/ /xroads.virginia.edu/ ~MA96/WCE/title.html Many thanks to John Bunch for his time and patience while I created this hypertextual thesis, and to my advisor Alan Howard for his great suggestions, support, and faith.,.I've truly enjoyed this year-long adventure! I'd like to dedicate this thesis, and my work throughout my Master's Program in English/ American Studies at the University of Virginia to my husband, Craig. Without his love, support, encouragement, and partnership, this thesis and degree could not have been possible. 1 INTRODUCTION The World's Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893, was the last and the greatest of the nineteenth century's World's Fairs. Nominally a celebration of Columbus' voyages 400 years prior, the Exposition was in actuality a reflection and celebration of American culture and society--for fun, edification, and profit--and a blueprint for life in modem and postmodern America. -

Old Market Character Appraisal Is Available Deadline of 21 February 2008

Conservation Area 16 Old Market Character Appraisal July 2008 www.bristol.gov.uk/conservation SA Hostel WINSFORD STREET FROME BRIDGE 1 PH 32 8 THRISS 26 to 30 E ET 24 2 LLST Old Market Convervation Area 1 2 20 R WADE STREET STRE 1 7 EET 3 Works N HA L AN Mm STREET 14 EST 8 Car Park LTTLE 6 7 RIVER STREET 2.0m 17 City Business Park 3 6 PH 15 to 11 Boundary of Conservation Area 20 PH 10 PH St Nicholas Church St Nicholas PH E STREET Church l Sub Sta Unive GP 1to32 Ho St Nicholas Lawford's G te TLE ANN usersal House 6 1 LIT Library 1to o15 DS GATE Lawford 11 t E Gate WADE STREE A WFOR T 1to18 D Wessex House 13 46 The Old Vica ge 59 4m ta 5 Car Park T 5 50 PH El T 16 City Business Park ub S 16 STREET S 18 19 PH RIVER INGTON ROAD 17 15 1 ELL NSTREET 1to22 W to 3 1 loucester 11 G House GREAT GEORGE STREE Somerset rence House GREAT AN 1to22 Ca TEMPLE WAY H Po ts o use TRINITY ROAD o44 (Community Centre) Friends Meeting TRINITY WALK House EY TCB 1t ERSL Telephone Exchange 1to17 41 ANE El Sub S Holy Trinity TCB to 48 Church Bristol City Mission Tyndall House 1to44 Po ice Station BRICK STREET Police Station 1to CLARENCE ROAD 1 17 22 20 9 Warehouse PH Jude St Coach and Horse 1to40 (PH) 8 E h Ves The 8 2 CLOS 1 sHo 85 1to2 HAYES 8 2 Warehouse 1 St Matthias try 23 25 81 ST MATTHIAS PARK 2 cel 6 1to 12 LANE E Subta 28 Th 90 41 S 40 (PH) 5 Cha 19 39 BRAGG'S 88 he Nave 75 86 3 21 T ER LANE TCB 84 7 T The LB 82 House 8 1 ES Old 1 The Tow r 0 78 Tannery30 UC St Matthias 51a 2 Guild 65 Heritage 16 Park GLO 1 7 12 29 5 7 0 t 3 o 31 62 5 6 495 2 4 10 18 33 -

Entuitive Credentials

CREDENTIALS SIMPLIFYING THE COMPLEX Entuitive | Credentials FIRM PROFILE TABLE OF CONTENTS Firm Profile i) The Practice 1 ii) Approach 3 iii) Better Design Through Technology 6 Services i) Structural Engineering 8 ii) Building Envelope 10 iii) Building Restoration 12 iv) Special Projects and Renovations 14 Sectors 16 i) Leadership Team 18 ii) Commercial 19 iii) Cultural 26 iv) Institutional 33 SERVICES v) Healthcare 40 vi) Residential 46 vii) Sports and Recreation 53 viii) Retail 59 ix) Hospitality 65 x) Mission Critical Facilities/Data Centres 70 xi) Transportation 76 SECTORS Image: The Bow*, Calgary, Canada FIRM PROFILE: THE PRACTICE ENTUITIVE IS A CONSULTING ENGINEERING PRACTICE WITH A VISION OF BRINGING TOGETHER ENGINEERING AND INTUITION TO ENHANCE BUILDING PERFORMANCE. We created Entuitive with an entrepreneurial spirit, a blank canvas and a new approach. Our mission was to build a consulting engineering firm that revolves around our clients’ needs. What do our clients need most? Innovative ideas. So we created a practice environment with a single overriding goal – realizing your vision through innovative performance solutions. 1 Firm Profile | Entuitive Image: Ripley’s Aquarium of Canada, Toronto, Canada BACKED BY DECADES OF EXPERIENCE AS CONSULTING ENGINEERS, WE’VE ACCOMPLISHED A GREAT DEAL TAKING DESIGN PERFORMANCE TO NEW HEIGHTS. FIRM PROFILE COMPANY FACTS The practice encompasses structural, building envelope, restoration, and special projects and renovations consulting, serving clients NUMBER OF YEARS IN BUSINESS throughout North America and internationally. 4 years. Backed by decades of experience as Consulting Engineers. We’re pushing the envelope on behalf of – and in collaboration with OFFICE LOCATIONS – our clients. They are architects, developers, building owners and CALGARY managers, and construction professionals. -

PATH Underground Walkway

PATH Marker Signs ranging from Index T V free-standing outdoor A I The Fairmont Royal York Hotel VIA Rail Canada H-19 pylons to door decals Adelaide Place G-12 InterContinental Toronto Centre H-18 Victory Building (80 Richmond 1 Adelaide East N-12 Hotel D-19 The Hudson’s Bay Company L-10 St. West) I-10 identify entrances 11 Adelaide West L-12 The Lanes I-11 W to the walkway. 105 Adelaide West I-13 K The Ritz-Carlton Hotel C-16 WaterPark Place J-22 130 Adelaide West H-12 1 King West M-15 Thomson Building J-10 95 Wellington West H-16 Air Canada Centre J-20 4 King West M-14 Toronto Coach Terminal J-5 100 Wellington West (Canadian In many elevators there is Allen Lambert Galleria 11 King West M-15 Toronto-Dominion Bank Pavilion Pacific Tower) H-16 a small PATH logo (Brookfield Place) L-17 130 King West H-14 J-14 200 Wellington West C-16 Atrium on Bay L-5 145 King West F-14 Toronto-Dominion Bank Tower mounted beside the Aura M-2 200 King West E-14 I-16 Y button for the floor 225 King West C-14 Toronto-Dominion Centre J-15 Yonge-Dundas Square N-6 B King Subway Station N-14 TD Canada Trust Tower K-18 Yonge Richmond Centre N-10 leading to the walkway. Bank of Nova Scotia K-13 TD North Tower I-14 100 Yonge M-13 Bay Adelaide Centre K-12 L TD South Tower I-16 104 Yonge M-13 Bay East Teamway K-19 25 Lower Simcoe E-20 TD West Tower (100 Wellington 110 Yonge M-12 Next Destination 10-20 Bay J-22 West) H-16 444 Yonge M-2 PATH directional signs tell 220 Bay J-16 M 25 York H-19 390 Bay (Munich Re Centre) Maple Leaf Square H-20 U 150 York G-12 you which building you’re You are in: J-10 MetroCentre B-14 Union Station J-18 York Centre (16 York St.) G-20 in and the next building Hudson’s Bay Company 777 Bay K-1 Metro Hall B-15 Union Subway Station J-18 York East Teamway H-19 Bay Wellington Tower K-16 Metro Toronto Convention Centre you’ll be entering. -

STREETSCAPE SURVEY Sdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfst Lawrence Neighbourhood

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw ertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwert yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopaSTREETSCAPE SURVEY sdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfSt Lawrence Neighbourhood 2 April 2014 ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj David Crawford klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklz xcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcv bnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklz xcvbnmqwe rtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjk lzxcvbnmrtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn 0 mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwe szxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx cvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnm qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw ertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmrtyuiopa sdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfNotes and references The St Lawrence Market BIA and the St Lawrence Neighbourhood ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj Association cover almost the same area from Yonge in the west to Parliament in the east and from Queen in the north to the railway This survey was corridor in the south. All Streets in the St Lawrence BIA and St klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzcarried out in Lawrence Neighbourhood Association area were surveyed except the February, March three `boundary streets`- Yonge, Queen and Parliament. The Survey and April 2014 and did not cover Lanes (as classified by the City) but a list of our lanes xcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvinvolved the use of (now all named, or in the final stages of naming) with some -

“Toronto Has No History!”: Indigeneity, Settler Colonialism, and Historical Memory in Canada’S Largest City

Document généré le 2 oct. 2021 00:00 Urban History Review Revue d'histoire urbaine “Toronto Has No History!” Indigeneity, Settler Colonialism, and Historical Memory in Canada’s Largest City Victoria Freeman Encounters, Contests, and Communities: New Histories of Race and Résumé de l'article Ethnicity in the Canadian City En 1884, au cours d’une semaine complète d’événements commémorant le 50e Volume 38, numéro 2, printemps 2010 anniversaire de l’incorporation de Toronto en 1834, des dizaines de milliers de gens fêtent l’histoire de Toronto et sa relation avec le colonialisme et URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/039672ar l’impérialisme britannique. Une analyse des fresques historiques du défilé de DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/039672ar la première journée des célébrations et de discours prononcés par Daniel Wilson, président de l’University College, et par le chef de Samson Green des Mohawks de Tyendinaga dévoile de divergentes approches relatives à la Aller au sommaire du numéro commémoration comme « politique par d’autres moyens » : d’une part, le camouflage du passé indigène de la région et la célébration de son avenir européen, de l’autre, une vision idéalisée du partenariat passé entre peuples Éditeur(s) autochtones et colons qui ignore la rôle de ces derniers dans la dépossession des Indiens de Mississauga. La commémoration de 1884 marque la transition Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine entre la fondation du village en 1793 et l’incorporation de la ville en 1834 comme « moment fondateur » et symbole de la supposée « autochtonie » des ISSN colons immigrants. Le titre de propriété acquis des Mississaugas lors de l’achat 0703-0428 (imprimé) de Toronto en 1787 est jugé sans importance, tandis que la Loi d’incorporation 1918-5138 (numérique) de 1834 devient l’acte symbolique de la modernité de Toronto. -

Heritage Property Research and Evaluation Report

ATTACHMENT NO. 10 HERITAGE PROPERTY RESEARCH AND EVALUATION REPORT WILLIAM ROBINSON BUILDING 832 YONGE STREET, TORONTO Prepared by: Heritage Preservation Services City Planning Division City of Toronto December 2015 1. DESCRIPTION Above: view of the west side of Yonge Street, north of Cumberland Street and showing the property at 832 Yonge near the south end of the block; cover: east elevation of the William Robinson Building (Heritage Preservation Services, 2014) 832 Yonge Street: William Robinson Building ADDRESS 832 Yonge Street (west side between Cumberland Street and Yorkville Avenue) WARD Ward 27 (Toronto Centre-Rosedale) LEGAL DESCRIPTION Concession C, Lot 21 NEIGHBOURHOOD/COMMUNITY Yorkville HISTORICAL NAME William Robinson Building1 CONSTRUCTION DATE 1875 (completed) ORIGINAL OWNER Sleigh Estate ORIGINAL USE Commercial CURRENT USE* Commercial * This does not refer to permitted use(s) as defined by the Zoning By-law ARCHITECT/BUILDER/DESIGNER None identified2 DESIGN/CONSTRUCTION Brick cladding with brick, stone and wood detailing ARCHITECTURAL STYLE See Section 2.iii ADDITIONS/ALTERATIONS See Section 2. iii CRITERIA Design/Physical, Historical/Associative & Contextual HERITAGE STATUS Listed on City of Toronto's Heritage Register RECORDER Heritage Preservation Services: Kathryn Anderson REPORT DATE December 2015 1 The building is named for the original and long-term tenant. Archival records indicate that the property, along with the adjoining site to the south was developed by the trustees of John Sleigh's estate 2 No architect or building is identified at the time of the writing of this report. Building permits do not survive for this period and no reference to the property was found in the Globe's tender calls 2. -

Inclusion on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register and Intention to Designate Under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act - 100 College Street

REPORT FOR ACTION Inclusion on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register and Intention to Designate under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act - 100 College Street Date: August 7, 2020 To: Toronto Preservation Board Toronto and East York Community Council From: Senior Manager, Heritage Planning, Urban Design, City Planning Wards: Ward 11 - University-Rosedale SUMMARY This report recommends that City Council state its intention to designate the property at 100 College Street under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act and include the property on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register. The Banting Institute at 100 College Street, is located on the north side of College Street in Toronto's Discovery District, on the southern edge of the Queen's Park/University of Toronto precinct, opposite the MaRS complex and the former Toronto General Hospital. Following the Nobel-Prize winning discovery of insulin as a life- saving treatment for diabetes in 1921-1922, the Banting Institute was commissioned by the University of Toronto to accommodate the provincially-funded Banting and Best Chair of Medical Research. Named for Major Sir Charles Banting, the five-and-a-half storey, Georgian Revival style building was constructed according to the designs of the renowned architectural firm of Darling of Pearson in 1928-1930. The importance of the historic discovery was recently reiterated in UNESCO's 2013 inscription of the discovery of insulin on its 'Memory of the World Register' as "one of the most significant medical discoveries of the twentieth century and … of incalculable value to the world community."1 Following research and evaluation, it has been determined that the property meets Ontario Regulation 9/06, which sets out the criteria prescribed for municipal designation under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act, for its design/physical, historical/associative and contextual value. -

Board of Directors Meeting

Board of Directors Meeting Agenda and Meeting Book THURSDAY, DECEMBER 5, 2019 FROM 08:30 AM TO 11:30 AM WATERFRONT TORONTO 20 BAY STREET, SUITE 1310 TORONTO, ON, M5J 2N8 Meeting Book - Board of Directors Meeting Agenda 8:30 a.m. 1. Motion to Approve Meeting Agenda Approval S. Diamond 8:35 a.m. 2. Declaration of Conflicts of Interest Declaration All 8:40 a.m. 3. Chair’s Opening Remarks Information S. Diamond 8:50 a.m. 4. Consent Agenda a) Draft Minutes of Open Session of the October 10 and 24, 2019 Board Approval All Meeting - Page 4 b) Draft Minutes of Open Session of the October 31, 2019 Board Approval All Meeting - Page 11 c) CEO Report - Page 15 Information G. Zegarac d) Finance Audit and Risk Management (FARM) Committee Chair's Information K. Sullivan Open Session Report - Page 44 e) Human Resources, Governance and Stakeholder Relations (HRGSR) Information S. Palvetzian Committee Chair's Open Session Report - Page 47 f) Investment, Real Estate and Quayside (IREQ) Committe Chair's Open Information M. Mortazavi Session Report - Page 48 9:00 a.m. 5. Port Lands Flood Protection (60% Design Stage Gate Status Approval D. Kusturin Update) Cover Sheet - Page 49 Presentation is attached as Appendix A to the Board Book 9:15 a.m. 6. Waterfront Toronto Priority Projects - Construction Update Information D. Kusturin Cover sheet - Page 50 Presentation is attached as Appendix B to the Board Book 9:30 a.m. 7. Motion to go into Closed Session Approval All Closed Session Agenda The Board will discuss items 8, 9 (a), (b), (c), (d) & (e) , 10, 11 and -

Report on the Brazilian Power System

Report on the Brazilian Power System Version 1.0 COUNTRY PROFILE Report on the Brazilian Power System IMPRINT COUNTRY PROFILE DISCLAIMER Report on the Brazilian Power System This report has been carefully prepared by the Version 1.0 authors in November 2018. We do not, however, take legal responsibility for its validity, accuracy, STUDY BY or completeness. Moreover, data as well as regulatory aspects of Brazil's energy policy are Agora Energiewende subject to change. Anna-Louisa-Karsch-Straße 2 10178 Berlin | Germany Instituto E+ Diálogos Energéticos Rua General Dionísio, 14 Humaitá | Rio de Janeiro | Brazil RJ | 22271 050 AUTHORS Carola Griebenow Amanda Ohara Funded by the Federal Ministry for Economics and Energy following a resolution by the German WITH KIND SUPPORT FROM Parliament. Luiz Barroso Ana Toni Markus Steigenberger REVIEW Roberto Kishinami & Munir Soares (iCS), This publication is available for Philipp Hauser (Agora Energiewende) download under this QR code. Proofreading: WordSolid, Berlin Please cite as: Maps: Wolfram Lange Agora Energiewende & Instituto E+ Diálogos Layout: UKEX GRAPHIC Urs Karcher Energéticos (2019): Report on the Brazilian Power Cover image: iStock.com/VelhoJunior System 155/01-CP-2019/EN www.agora-energiewende.de Publication: September 2019 www.emaisenergia.org Preface Dear readers, The energy transition is transforming our economies government. However, the successful transition to with increasing speed: it will have profound impacts the energy system of the future in Brazil will require on communities, industries, trade and geopolitical a broad and inclusive societal dialogue. Only if all relations. Concerns about climate change and energy stakeholder interests are recognised, will it be possi- security have been at the root of new technological ble to minimize negative impacts and maximize the developments. -

2012 Winners List

® 2012 Winners List Category 1: American-Style Wheat Beer, 23 Entries Category 29: Baltic-Style Porter, 28 Entries Gold: Wagon Box Wheat, Black Tooth Brewing Co., Sheridan, WY Gold: Baltic Gnome Porter, Rock Bottom Denver, Denver, CO Silver: 1919 choc beer, choc Beer Co., Krebs, OK Silver: Battle Axe Baltic Porter, Fat Heads Brewery, North Olmsted, OH Bronze: DD Blonde, Hop Valley Brewing Co., Springfield, OR Bronze: Dan - My Turn Series, Lakefront Brewery, Milwaukee, WI Category 2: American-Style Wheat Beer With Yeast, 28 Entries Category 30: European-Style Low-Alcohol Lager/German-Style, 18 Entries Gold: Whitetail Wheat, Montana Brewing Co., Billings, MT Silver: Beck’s Premier Light, Brauerei Beck & Co., Bremen, Germany Silver: Miners Gold, Lewis & Clark Brewing Co., Helena, MT Bronze: Hochdorfer Hopfen-Leicht, Hochdorfer Kronenbrauerei Otto Haizmann, Nagold-Hochdorf, Germany Bronze: Leavenworth Boulder Bend Dunkelweizen, Fish Brewing Co., Olympia, WA Category 31: German-Style Pilsener, 74 Entries Category 3: Fruit Beer, 41 Entries Gold: Brio, Olgerdin Egill Skallagrimsson, Reykjavik, Iceland Gold: Eat A Peach, Rocky Mountain Brewery, Colorado Springs, CO Silver: Schönramer Pils, Private Landbrauerei Schönram, Schönram, Germany Silver: Da Yoopers, Rocky Mountain Brewery, Colorado Springs, CO Bronze: Baumgartner Pils, Brauerei Jos. Baumgartner, Schaerding, Austria Bronze: Blushing Monk, Founders Brewing Co., Grand Rapids, MI Category 32: Bohemian-Style Pilsener, 62 Entries Category 4: Fruit Wheat Beer, 28 Entries Gold: Starobrno Ležák, -

Toronto Arch.CDR

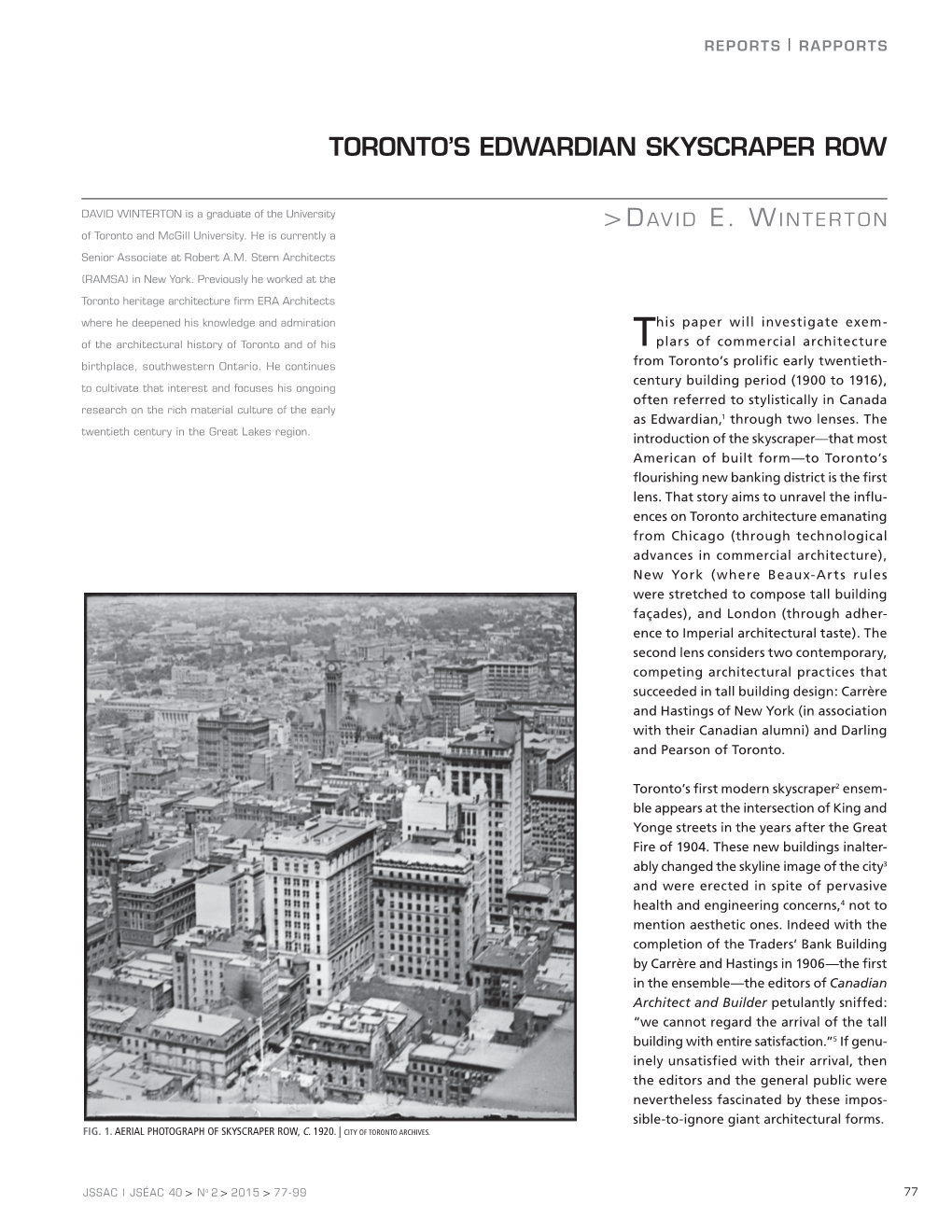

The Architectural Fashion of Toronto Residential Neighbourhoods Compiled By: RASEK ARCHITECTS LTD RASE K a r c h i t e c t s www.rasekarchitects.com f in 02 | The Architectural Fashion of Toronto Residential Neighbourhoods RASEK ARCHITECTS LTD Introduction Toronto Architectural Styles The majority of styled houses in the United States and Canada are The architecture of residential houses in Toronto is mainly influenced by its history and its culture. modeled on one of four principal architectural traditions: Ancient Classical, Renaissance Classical, Medieval or Modern. The majority of Toronto's older buildings are loosely modeled on architectural traditions of the British Empire, such as Georgian, Victorian, and Edwardian architecture. Toronto was traditionally a peripheral city in the The earliest, the Ancient Classical Tradition, is based upon the monuments architectural world, embracing styles and ideas developed in Europe and the United States with only limited of early Greece and Rome. local variation. A few unique styles of architecture have emerged in Toronto, such as the bay and gable style house and the Annex style house. The closely related Renaissance Classical Tradition stems from a revival of interest in classicism during the Renaissance, which began in Italy in the The late nineteenth century Torontonians embraced Victorian architecture and all of its diverse revival styles. 15th century. The two classical traditions, Ancient and Renaissance, share Victorian refers to the reign of Queen Victoria (1837-1901), called the Victorian era, during which period the many of the same architectural details. styles known as Victorian were used in construction. The styles often included interpretations and eclectic revivals of historic styles mixed with the introduction of Middle Eastern and Asian influences.