Redacting Tosafot on the Talmud: Part I―Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A USER's MANUAL Part 1: How Is Halakhah Organized?

TORAHLEADERSHIP.ORG RABBI ARYEH KLAPPER HALAKHAH: A USER’S MANUAL Part 1: How is Halakhah Organized? I. How is Halakhah Organized? 4 case studies a. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1, and gemara thereupon b. Support of the poor Peiah, Bava Batra, Matnot Aniyyim, Yoreh Deah) c. Conversion ?, Yevamot, Issurei Biah, Yoreh Deah) d. Mourning Moed Qattan, Shoftim, Yoreh Deiah) Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 From what time may one recite the Shema in the evening? From the hour that the kohanim enter to eat their terumah Until the end of the first watch, in the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer. The Sages say: Until midnight. Rabban Gamliel says: Until morning. It happened that his sons came from a wedding feast. They said to him: We have not yet recited the Shema. He said to them: If it has not yet morned, you are obligated to recite it. Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 2a What is the context of the Mishnah’s opening “From when”? Also, why does it teach about the evening first, rather than about the morning? The context is Scripture saying “when you lie down and when you arise” (Devarim 6:7, 11:9). what the Mishnah intends is: “The time of the Shema of lying-down – when is it?” Alternatively: The context is Creation, as Scripture writes “There was evening and there was morning”. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 (continued) Not only this – rather, everything about which the Sages say until midnight – their mitzvah is until morning. The burning of fats and organs – their mitzvah is until morning. All sacrifices that must be eaten in a day – their mitzvah is until morning. -

Fooling the Tax Collector

Schachter, rosh yeshiva of Rabbi Isaac Elchanan In introducing a new metaphor — that Theological Seminary (RIETS) at Yeshiva citizens of a modern democracy are more University. “It is important to note that today like partners than subjects — into formalized the basis for taxation is totally different from Jewish legal thinking, Schachter has taken what it was in talmudic times.” According to a a first important step in opening up an en- contemporary understanding of Jewish law, we tirely new vista from which to think about ought to ground the obligation to pay taxes not the legitimacy of taxes and the responsibility SHMA.COM in the anachronistic notion of dina d’malchuta of partners to participate in public policy dis- dina; rather, we should invoke the talmudic cussions. In this alternative view, it is not us concept of shutfim or partnership. Schachter versus them, but rather “we the people” who concludes, “All people who live in the same must formulate fair tax rules and just public city, state, and country are considered ‘shut- policies. It follows directly from Schachter’s fim’ with respect to the services provided by new formulation that as Jewish partners in that city, state, and country. The purpose be- this process, we have a unique right and obli- hind the taxes is no longer ‘to enrich the king’ gation to bring to our fellow citizens the best in the slightest.” (Torahweb.org) of Jewish legal and ethical thinking. Fooling the Tax Collector: Why the Rabbis Once Approved DAVID BRODSKY abbi Naftali Tzvi Weisz, the Spinka Luke 3:12, 5:27–30, 7:29, 7:34, 15:1, and 18:9– Rebbe of Boro Park, and the great-great- 14), just as the Mishnah associates them with Rgrandson of R. -

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach Today (?)

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach today (?) Three girls in Israel were detained by the Israeli Police (2018). The girls are activists of the “Return to the Mount” (Chozrim Lahar) movement. Why were they detained? They had posted Arabic signs in the Muslim Quarter calling upon Muslims to leave the Temple Mount area until Friday night, in order to allow Jews to bring the Korban Pesach. This is the fourth time that activists of the movement will come to the Old City on Erev Pesach with goats that they plan to bring as the Korban Pesach. There is also an organization called the Temple Institute that actively is trying to bring back the Korban Pesach. It is, of course, very controversial and the issues lie at the heart of one of the most fascinating halachic debates in the past two centuries. 1 The previous mishnah was concerned with the offering of the paschal lamb when the people who were to slaughter it and/or eat it were in a state of ritual impurity. Our present mishnah is concerned with a paschal lamb which itself becomes ritually impure. Such a lamb may not be eaten. (However, we learned incidentally in our study of 5:3 that the blood that gushed from the lamb's throat at the moment of slaughter was collected in a bowl by an attendant priest and passed down the line so that it could be sprinkled on the altar). Our mishnah states that if the carcass became ritually defiled, even if the internal organs that were to be burned on the altar were intact and usable the animal was an invalid sacrifice, it could not be served at the Seder and the blood should not be sprinkled. -

Women's Testimony and Talmudic Reasoning

Kedma: Penn's Journal on Jewish Thought, Jewish Culture, and Israel Volume 2 Number 2 Fall 2018 Article 8 2020 Women’s Testimony and Talmudic Reasoning Deena Kopyto University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/kedma Part of the Jewish Studies Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/kedma/vol2/iss2/8 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Women’s Testimony and Talmudic Reasoning Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License This article is available in Kedma: Penn's Journal on Jewish Thought, Jewish Culture, and Israel: https://repository.upenn.edu/kedma/vol2/iss2/8 Women’s Testimony and Talmudic Reasoning Deena Kopyto Introduction Today, being a witness is often considered a burden – an obligation that courts force people to fulfill. In contrast, in Talmudic-era Babylonia and ancient Israel, testifying was a privilege that certain groups, including slaves, women, and children, did not enjoy. While minors should be barred from participating in courts, and still largely are today, the status of women in Talmudic courts poses a much trickier question. Through this historical and Talmudic analysis, I aim to determine the root of this ban. The reasons for the ineligibility of female testimony range far and wide, but most are not explicitly mentioned in the Talmud. Perhaps women in Talmudic times were infrequently called as witnesses, and rabbis banned women from participation in courts in order to further crystallize this patriarchal structure. -

Guardianship for Orphans in Talmudic Law

Guardianship for Orphans in Talmudic law AMIHAI RADZYNER ABSTRACT The article reviews the Talmudic institution of guardianship for orphans, as it appears in sources from Palestine and Babylon, mostly from the second to the fifth centuries CE. It is likely that the foundations of this institution are found in foreign law, but after it was absorbed in Jewish law, it began to build an independent life, and was not necessarily affected by its legal system of origin. The design of the institution was mainly conducted by the Jewish sages of the second-century (Tannaim). The Mishnah and Tosefta are already showing a fairly well-developed system of guardianship laws. This system was not changed substantially afterward, and the later Talmudic sages (Amoraim) continued to develop the institution upon the foundation created by their pre- decessors. The Talmudic sources present a fairly well-developed institution, from its creation through the duties of the guardian during his tenure to the end of the guardianship term. 245 INTRODUCTION It seems that like in other instances, the Greek term for guardian – epitropos which appears many times in Talmudic literature shows us ,1('אפוטרופוס') that it involves an institution which was created in Talmudic law under the influence of Greek and Roman Law, two legal traditions that were prevalent in Palestine at the time of the creation of the institution of guardianship.2 This does not mean, at the same time that the principles of the laws of Talmudic guardianship, which I shall not discuss in this short article, are identical to those of any known Greek or Roman law.3 Within this framework I shall con- fine my analysis to Talmudic Law and its principles exclusively. -

Syllabus Beth Berkowitz Jewish Theological Seminary Animals in Rabbinic

TAL 6150 “Humans and Other Animals in Talmudic Torts” Prof. Beth Berkowitz The Jewish Theological Seminary of America Fall 2010 Monday/Wednesday 10:20-12:10 “Among nonhumans and separate from nonhumans there is an immense multiplicity of other living things that cannot in any way be homogenized, except by means of violence and willful ignorance, within the category of what is called the animal or animality in general.” Jacques Derrida “The Animal That Therefore I Am” Theme of Course Human beings have long considered themselves unique among animals. In recent decades, new research on animal cognition and the rise of the environmentalist movement have challenged the conviction that we are superior to – and have the right to exploit – other animal species. This course will explore the conceptualization of animals within classical rabbinic law. Slaughtering, sacrificing, and eating animals are the most prominent legal topics, but the Mishnah also discusses buying, selling, owning, inheriting, stealing, judging, and worshipping animals, as well as keeping them as pets, using them for labor, gambling with them, and having sex with them. Our course will focus on rabbinic laws about injury to and by animals, which is most often embodied by the “goring ox,” a legal motif inherited from the Torah (which was probably in turn borrowed from the Laws of Hammurabi). We will keep in mind the broader rabbinic discourse about animals as we ask: • According to rabbinic assumption, what is the character of animal cognition, communication, intention, emotion? -

The Prophet Jeremiah in the Talmud and Midrash Chronology

Sun 4 Nov 2007 Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Joint series on Jeremiah with Beth El Hebrew Congregation The Prophet Jeremiah in the Talmud and Midrash Chronology 640-609 BCE: Josiah [Yoshiyahu], King of Judah. Marched against Pharaoh Necho and was killed at Megiddo. Strong religious reforms, restoration of Jewish practices, Temple-centered. 626-585 BCE: Jeremiah’s [Yirmiahu] 41 years of prophecy. Torn between love of Jews and love of Judaism. 609 BCE: Jehoahaz, son of Josiah, King of Judah. 3-month reign, died in exile in Egypt. 609-598 BCE: Jehoiakim, son of Josiah, King of Judah. Died during siege of Jerusalem. Burned scroll of Lamentations. Return of idolatry and corruption. 598 BCE: Jeconiah [Jehoiachin], son of Jehoiakim, King of Judah. Was 18, reigned 3 months, exiled to Babylon. 598-587 BCE: Zedekiah [Tzidkiyahu], son of Josiah, last king of Judah . Was 21 when began reign, exiled to Babylon. 589-586 BCE: Siege and sack of Jerusalem, destruction of Temple and exile to Babylon ========================== Authorship Jeremiah wrote the books of Jeremiah, Kings, and Lamentations (Talmud) Moses received the Torah from God and wrote the Book of Job, Joshua wrote his book and the last eight verses of Deuteronomy (that is, the account of the death of Moses); Samuel wrote his book, Judges and Ruth; David wrote the Psalms; Jeremiah wrote his book, the Book of Kings and Lamentations; Hezekiah and his council wrote Isaiah, Proverbs, Song of Songs, and Ecclesiastes; the men of the Great Assembly wrote Ezekiel, the Twelve Prophets, Daniel, and the Scroll of Esther; Ezra wrote his book and the genealogy of Chronicles down to himself. -

Symposium: "You Have Chosen Us from Amongst the Nations"

Symposium (Guide to the Perplexed III, 49). Rav Kook writes: Symposium By Jonathan Blass One might think that the entire difference between Israel and the nations is that difference [in the realm of action] which is given prominence by the active observance of mitzvot ….This view is mistaken.… It is the element of neshamah that sets aRav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook’s under- Israel’s character apart as a distinct unit, unique in the world. standingH of what makes Am Yisrael God’s Chosen People From that difference spring all the differences in behavior [i.e., had practical as well as theoretical relevance for his genera- mitzvot], and even when these last are impaired [by lack of tion, and continues to be vitally important to this day. It observance], that impairment cannot touch the … psychic ele- Ò You Have formed the basis for Rav Kook’s cooperation with the non- ÒYou Have ment from which they derive. Therefore the difference between religious and anti-religious pioneers of his period (see Israel and the nations will remain forever (Orot Yisrael 5:7). Iggerot HaR’Iyyah, Iggeret 555) and underlies the belief of What is the nature of Israel’s national identity? What is Am his disciples that the founding of even a secular Jewish state Yisrael ? Rav Kook teaches that Israel’s identity is one with has not only political but also religious significance. Rav God’s wisdom and will. By its nature, Am Yisrael strives to ChosenChosen UsUs Kook teaches us that what distinguishes Israel from the realize those truths embodied in the Torah. -

Violent Video Games, but It Does Indicate What Happens When Children Make Media the Center of Their Lives

1 Violent and Defamatory Video Games Rabbi Elliot Dorff and Rabbi Joshua Hearshen February 4, 2010 EH 21:1.2010 This paper was approved on February 4, 2010, by a vote of twelve in favor (12-0-1). Voting in favor: Rabbis Kassel Abelson, Miriam Berkowitz, Elliot Dorff, Robert Fine, Susan Grossman, Josh Heller, Jane Kanarek, Daniel Nevins, Avram Reisner, Jay Stein, Steven Wernick and David Wise. Abstaining: Rabbi Adam Kligfeld. The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halakhah for the Conservative movement. The individual rabbi, however, is the authority for the interpretation and application of all matters of halakhah. She’elah: May Jews play violent or defamatory video games? Te’shuvah: The video game industry accounts for an enormous percentage of the entertainment industry today. 1 According to a September 2008 survey by the Pew Research Center, 97% of all teenagers play video games in some format. 2 While First Amendment rights to free speech assure that the content of these games is legal in American law, their ethical status varies widely. The variety of games available today is great, and the good to be gained from many of them may also be great. They stimulate the minds of the elderly, and they raise preparedness scores of those about to enter the Israeli army, and they help youngsters learn everything from music to mathematics. In a portion of the games, however, the material is morally questionable and may even be harmful or immoral on other grounds. These include what we are calling “violent and defamatory games.” By “violent” we mean gratuitous brute force intended 1 http://www.mediafamily.org the Mediawise Video Game Report Card is published periodically by the National Institute on Media and the Family. -

What Sugyot Should an Educated Jew Know?

What Sugyot Should An Educated Jew Know? Jon A. Levisohn Updated: May, 2009 What are the Talmudic sugyot (topics or discussions) that every educated Jew ought to know, the most famous or significant Talmudic discussions? Beginning in the fall of 2008, about 25 responses to this question were collected: some formal Top Ten lists, many informal nominations, and some recommendations for further reading. Setting aside the recommendations for further reading, 82 sugyot were mentioned, with (only!) 16 of them duplicates, leaving 66 distinct nominated sugyot. This is hardly a Top Ten list; while twelve sugyot received multiple nominations, the methodology does not generate any confidence in a differentiation between these and the others. And the criteria clearly range widely, with the result that the nominees include both aggadic and halakhic sugyot, and sugyot chosen for their theological and ideological significance, their contemporary practical significance, or their centrality in discussions among commentators. Or in some cases, perhaps simply their idiosyncrasy. Presumably because of the way the question was framed, they are all sugyot in the Babylonian Talmud (although one response did point to texts in Sefer ha-Aggadah). Furthermore, the framing of the question tended to generate sugyot in the sense of specific texts, rather than sugyot in the sense of centrally important rabbinic concepts; in cases of the latter, the cited text is sometimes the locus classicus but sometimes just one of many. Consider, for example, mitzvot aseh she-ha-zeman gerama (time-bound positive mitzvoth, no. 38). The resulting list is quite obviously the product of a committee, via a process of addition without subtraction or prioritization. -

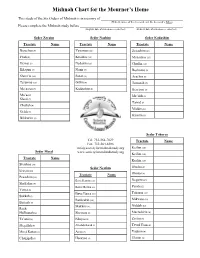

English Mishnah Chart

Mishnah Chart for the Mourner’s Home This study of the Six Orders of Mishnah is in memory of (Hebrew names of the deceased, and the deceased’s father) Please complete the Mishnah study before (English date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) (Hebrew date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) Seder Zeraim Seder Nashim Seder Kodashim Tractate Name Tractate Name Tractate Name Berachos (9) Yevamos (16) Zevachim (14) Peah (8) Kesubos (13) Menachos (13) Demai (7) Nedarim (11) Chullin (12) Kilayim (9) Nazir (9) Bechoros (9) Shevi’is (10) Sotah (9) Arachin (9) Terumos (11) Gittin (9) Temurah (7) Ma’asros (5) Kiddushin (4) Kereisos (6) Ma’aser Me’ilah (6) Sheni (5) Tamid (7) Challah (4) Middos (5) Orlah (3) Kinnim (3) Bikkurim (3) Seder Tohoros Tel: 732-364-7029 Tractate Name Fax: 732-364-8386 [email protected] Keilim (10) Seder Moed www.societyformishnahstudy.org Keilim (10) Tractate Name Keilim (10) Shabbos (24) Seder Nezikin Oholos (9) Eruvin (10) Tractate Name Oholos (9) Pesachim (10) Bava Kamma (10) Negaim (14) Shekalim (8) Bava Metzia (10) Parah (12) Yoma (8) Bava Basra (10) Tohoros (10) Sukkah (5) Sanhedrin (11) Mikvaos (10) Beitzah (5) Makkos (3) Niddah (10) Rosh HaShanah (4) Shevuos (8) Machshirin (6) Ta’anis (4) Eduyos (8) Zavim (5) Megillah (4) Avodah Zarah (5) Tevul Yom (4) Moed Kattan (3) Avos (5) Yadaim (4) Chagigah (3) Horayos (3) Uktzin (3) • Our Sages have said that Asher, son of the Patriarch Jacob sits at the opening to Gehinom (Purgatory), and saves [from entering therein] anyone on whose behalf Mishnah is being studied . -

Of the Mishnah, Bavli & Yerushalmi

0 Learning at SVARA SVARA’s learning happens in the bet midrash, a space for study partners (chevrutas) to build a relationship with the Talmud text, with one another, and with the tradition—all in community and a queer-normative, loving culture. The learning is rigorous, yet the bet midrash environment is warm and supportive. Learning at SVARA focuses on skill-building (learning how to learn), foregrounding the radical roots of the Jewish tradition, empowering learners to become “players” in it, cultivating Talmud study as a spiritual practice, and with the ultimate goal of nurturing human beings shaped by one of the central spiritual, moral, and intellectual technologies of our tradition: Talmud Torah (the study of Torah). The SVARA method is a simple, step-by-step process in which the teacher is always an authentic co-learner with their students, teaching the Talmud not so much as a normative document prescribing specific behaviors, but as a formative document, shaping us into a certain kind of human being. We believe the Talmud itself is a handbook for how to, sometimes even radically, upgrade our tradition when it no longer functions to create the most liberatory world possible. All SVARA learning begins with the CRASH Talk. Here we lay out our philosophy of the Talmud and the rabbinic revolution that gave rise to it—along with important vocabulary and concepts for anyone learning Jewish texts. This talk is both an overview of the ultimate goals of the Jewish enterprise, as well as a crash course in halachic (Jewish legal) jurisprudence. Beyond its application to Judaism, CRASH Theory is a simple but elegant model of how all change happens—whether societal, religious, organizational, or personal.