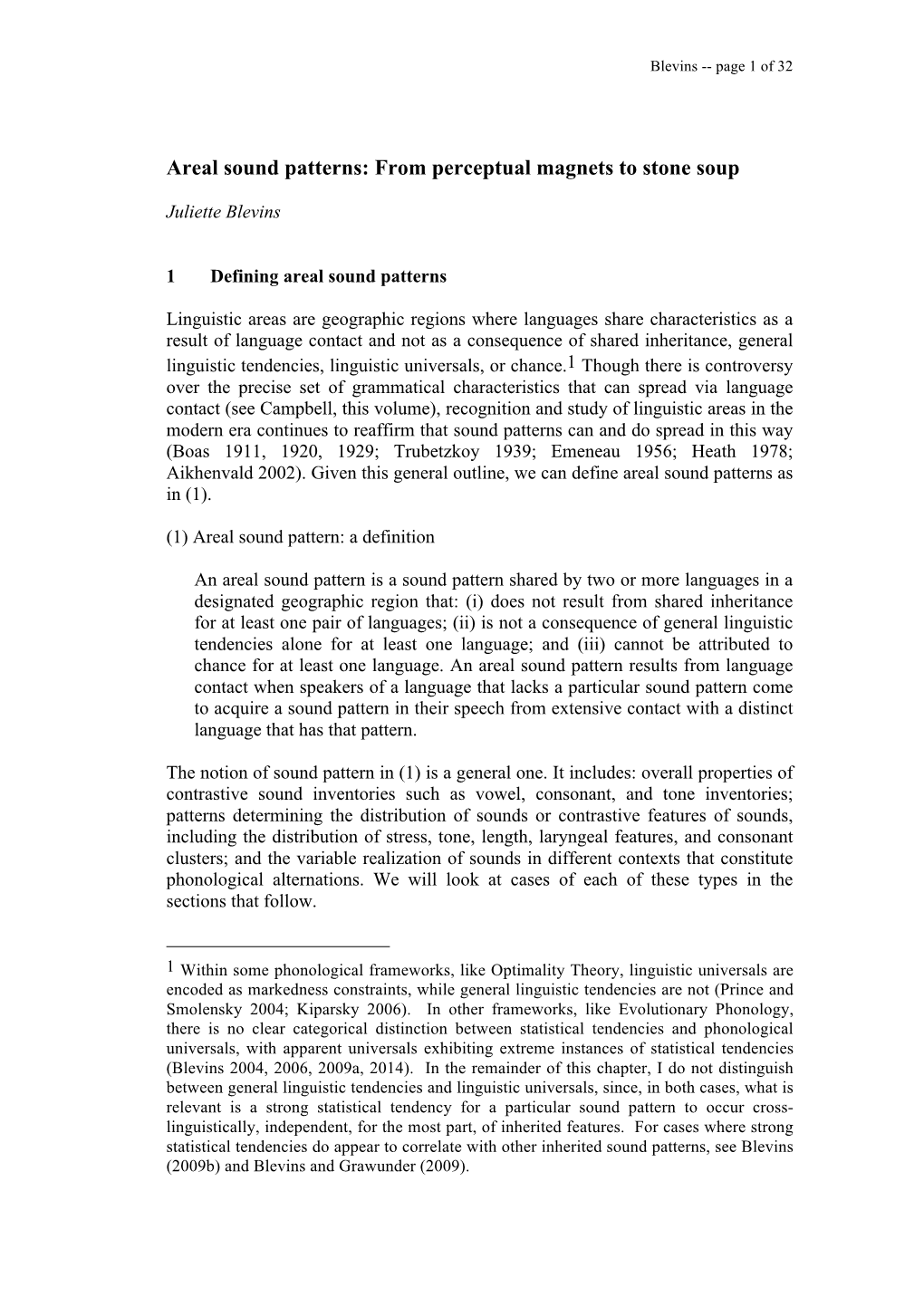

Areal Sound Patterns: from Perceptual Magnets to Stone Soup

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mehri Ejective Fricatives: an Acoustic Study Rachid Ridouane, Cédric Gendrot, Rajesh Khatiwada

Mehri ejective fricatives: an acoustic study Rachid Ridouane, Cédric Gendrot, Rajesh Khatiwada To cite this version: Rachid Ridouane, Cédric Gendrot, Rajesh Khatiwada. Mehri ejective fricatives: an acoustic study. 18th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, Aug 2015, Glasgow, United Kingdom. halshs- 01287685 HAL Id: halshs-01287685 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01287685 Submitted on 15 Mar 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Mehri ejective fricatives: an acoustic study Rachid Ridouane, Cédric Gendrot, Rajesh Khatiwada Laboratoire de Phonétique et Phonologie (CNRS/Sorbonne Nouvelle), Paris ABSTRACT sequence of a pulmonic fricative followed by a glottal stop [3]. The second strategy, observed in Ejective consonants are not very common cross- Tlingit, was to produce ejective fricatives with a linguistically. Even less common is the occurrence much narrower constriction than was used in their of ejective fricatives. This infrequency is generally pulmonic counterparts [4]. This allowed for glottal attributed to the incompatibility of two aerodynamic closure to overlap the entire frication duration while requirements: a continuing flow of air to create noise producing high intra-oral pressure, suggesting that frication and an increasing intraoral air pressure to they were indeed ejective fricatives. -

High Vowel Fricativization As an Areal Feature of the Northern Cameroon Grassfields

High vowel fricativization as an areal feature of the northern Cameroon Grassfields Matthew Faytak WOCAL 8, | August 23, 2015 Overview High vowel fricativization is an areal or contact feature of the northern Grassfields, which carries implications for Niger-Congo reconstructions 1. What is (not) a fricativized vowel? 2. Where are they (not)? 3. Why is this interesting? Overview High vowel fricativization is an areal or contact feature of the northern Grassfields, which carries implications for Niger-Congo reconstructions 1. What is (not) a fricativized vowel? 2. Where are they (not)? 3. Why is this interesting? Fricative vowels Vowels with a fricative-like supralaryngeal constriction, which may or may not consistently result in audible fricative noise Not intended to encompass: • Devoiced or voiceless vowels Smith (2003) • Pre-/post-aspirated vowels Helgason (2002) Mortensen (2012) • Articulatory overlap at high speech rate • Wall noise sources in high vowels Shadle (1990) Prior mention Vowels that do fit one or both of the given definitions: • Apical vowels in Chinese Lee (2005) Feng (2007) Lee-Kim (2014) • Viby-i, G¨oteborges-i, etc. in Swedish Holmberg (1976) Engstrand et al. (2000) Sch¨otzet al. (2011) • Fricative vowels in Bantoid Medjo Mv´e(1997) Connell (2007) Articulatory evidence of constriction Olson and Meynadier (2015) Articulatory evidence of constriction z v " " High vowel fricativization (HVF) Fricative vowels arise from normal high vowels /i u/, often in tandem with raising of the next-lowest vowels Faytak (2014) i u e o i -

Vowel Acoustics Reliably Differentiate Three Coronal Stops of Wubuy Across Prosodic Contexts

Vowel acoustics reliably differentiate three coronal stops of Wubuy across prosodic contexts Rikke L. BundgaaRd-nieLsena, BRett J. BakeRb, ChRistian kRoosa, MaRk haRveyc and CatheRine t. Besta,d aMARCS Auditory Laboratories, University of Western Sydney bSchool of Languages and Linguistics, University of Melbourne cSchool of Humanities and Social Science, University of Newcastle dHaskins Laboratories, New Haven Abstract The present study investigates the acoustic differentiation of three coronal stops in the indigenous Australian language Wubuy. We test independent claims that only VC (vowel-into-consonant) transitions provide robust acoustic cues for retroflex as compared to alveolar and dental coronal stops, with no differentiating cues among these three coronal stops evident in CV (consonant-into-vowel) transitions. The four-way stop distinction /t, t̪ , ʈ, c/ in Wubuy is contrastive word-initially (Heath 1984) and by implication utterance-initially, i.e., in CV-only contexts, which suggests that acoustic differentiation should be expected to occur in the CV transitions of this language, including in initial positions. Therefore, we examined both VC and CV formant transition information in the three target coronal stops across VCV (word-internal), V#CV (word-initial but utterance-medial) and ##CV (word- and utterance-initial), for /a / vowel contexts, which provide the optimal environment for investigating formant transitions. Results confirm that these coro- nal contrasts are maintained in the CVs in this vowel context, and in all three posi- tions. The patterns of acoustic differences across the three syllable contexts also provide some support for a systematic role of prosodic boundaries in influencing the degree of coronal stop differentiation evident in the vowel formant transitions. -

Lecture 5 Sound Change

An articulatory theory of sound change An articulatory theory of sound change Hypothesis: Most common initial motivation for sound change is the automation of production. Tokens reduced online, are perceived as reduced and represented in the exemplar cluster as reduced. Therefore we expect sound changes to reflect a decrease in gestural magnitude and an increase in gestural overlap. What are some ways to test the articulatory model? The theory makes predictions about what is a possible sound change. These predictions could be tested on a cross-linguistic database. Sound changes that take place in the languages of the world are very similar (Blevins 2004, Bateman 2000, Hajek 1997, Greenberg et al. 1978). We should consider both common and rare changes and try to explain both. Common and rare changes might have different characteristics. Among the properties we could look for are types of phonetic motivation, types of lexical diffusion, gradualness, conditioning environment and resulting segments. Common vs. rare sound change? We need a database that allows us to test hypotheses concerning what types of changes are common and what types are not. A database of sound changes? Most sound changes have occurred in undocumented periods so that we have no record of them. Even in cases with written records, the phonetic interpretation may be unclear. Only a small number of languages have historic records. So any sample of known sound changes would be biased towards those languages. A database of sound changes? Sound changes are known only for some languages of the world: Languages with written histories. Sound changes can be reconstructed by comparing related languages. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

For the Third Case. Fairly Detailed Phonetic and Distributional Data Are Also Utilized

nof:J1611tNT nmsohlw ED 030 098 AL 001 858 By-Moskowitz, Arlene I. The Two-Year -Old Stage in the Acquisition of English Phonology. Spons Agency-American Cuunoi of Learned Societies, New Yofk, N.Y.; Social Science Research Council, Washington, D.C. Pub Date 29 Dec 68 Note-24p.. Slightly expanded verzion of i. paper presented at the 43rd Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America, New York City, December 29, 1968. EDRS Price MF-1025 HC-$1.30 Descriptors -*Child Language, Consonants, Distinctive Features, Early Childhood, Enghsh. Language Development, Language Learning Levels, Language Patterns, Language Typology, Phonemes. Phonetic Analysis. ePhonogi,gy, Vowels The phonologies of three English-speaking children at approximately two years of age are examined. Two of the analyses are based on pOblished:studies. the third is based on observations and recordings made by the author. Summary statements on phonemic inventories and on correspondences with the adult model are presented. For the third case. fairly detailed phonetic and distributional data are also utilized. The paper attempts to draw conclusions about typical difficulties of phonological development at this stage and possible strategies used by children in attaining the adult norms. (Author/JD) . r U.S. DEPARTMENT Of HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE Of EDUCATION TINS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVEDFROM DIE PERSON OR 016ANIZATION 0116INATIN6 IT.POINTS Of VIEW OR OPINIONS STAB DO NOT IIKESSAMLY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFRCEOf EDUCATION POSITION OR POUCY. TR TWO*TIAMOLD SUM IN Mg ACQUISITION orMUSHPHOMOLO0Y1 Arlen* I. Noskovitz AL 001858 0. Introduction. It is a widely held view among linguists and paycholinguists that the phonology of a child's speech at any 2 ilage during the acquisition process is structured. -

Pharyngealization in Assiri Arabic: an Acoustic Analysis

SST 2010 Pharyngealization in Assiri Arabic: an acoustic analysis. Saeed Shar, John Ingram School of Languages and Cross Cultural Studies, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia [email protected], j.ingram @uq.edu.au capital of the southern region of Saudi Arabia. The Assiri Abstract dialect serves as a standard dialect for speakers of other local Five native speakers of Assiri Arabic read word lists dialects in the region. The study is part of a wider comprising contrasting pairs of plain and emphatic investigation of the acoustic and articulatory mappings of (pharyngealized) consonants in three vocalic environments guttural sounds in Assiri Arabic, using MRI. (/i/, /a/, /u/). Although considerable individual variation in expression was apparent from auditory and acoustic analysis 2. Method of the tokens, the most consistent acoustic correlate of the plain-emphatic contrast appeared to lie in the transition phase 2.1. Subjects of the accompanying vowel formant trajectories, involving a The subjects were five male native speakers of the Assiri raising of F1 and lowering of F2. A statistical analysis dialect of Arabic, one of them is the first author of this paper. (ANOVA) of the formant targets involving interactions of The age range of the subjects is 30 - 35 years. All have normal pharyngealization with, consonant , vowel, and subject factors neurological history and no apparent speech or hearing is presented, with discussion of implications for articulatory disorders. All recorded data were taken in Australia using the targets for the plain-emphatic contrast, as assessed by MRI same computer, microphone and other settings. During imaging in the same group of subjects. -

Complexity As L2-Difficulty : Implications for Syntactic Change

Erschienen in: Theoretical Linguistics ; 45 (2019), 3-4. - S. 183-209 https://dx.doi.org/10.1515/tl-2019-0012 Theoretical Linguistics 2019; 45(3-4): 183–209 George Walkden* and Anne Breitbarth Complexity as L2-difficulty: Implications for syntactic change https://doi.org/10.1515/tl-2019-0012 Abstract: Recent work has cast doubt on the idea that all languages are equally complex; however, the notion of syntactic complexity remains underexplored. Taking complexity to equate to difficulty of acquisition for late L2 acquirers, we propose an operationalization of syntactic complexity in terms of uninterpret- able features. Trudgill’s sociolinguistic typology predicts that sociohistorical situations involving substantial late L2 acquisition should be conducive to simplification, i.e. loss of such features. We sketch a programme for investigat- ing this prediction. In particular, we suggest that the loss of bipartite negation in the history of Low German and other languages indicates that it may be on the right track. Keywords: sociolinguistic typology, syntactic change, L2 acquisition, simplification, Interpretability Hypothesis 1 Context and big picture 1.1 Typology, complexity, and language change The traditional notion that all languages are equally complex, as expressed in Hockett (1958), has recently come under attack from a number of quarters. Notably, in his seminal work Sociolinguistic Typology, Trudgill (2011) has sug- gested that different types of sociolinguistic situation lead to differential sim- plification and complexification: for instance, long-term co-territorial language contact is predicted to lead to additive complexification, whereas short-term contact involving extensive adult second-language (L2) use is predicted to lead to simplification. -

The Kortlandt Effect

The Kortlandt Effect Research Master Linguistics thesis by Pascale Eskes Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts July 2020 Supervisor: Dr. Alwin Kloekhorst Second reader: Prof. dr. Alexander Lubotsky ii Abstract It has been observed that pre-PIE *d sometimes turns into PIE *h₁, also referred to as the Kortlandt effect, but much is still unclear about the occurrence and nature of this change. In this thesis, I provide an elaborate discussion aimed at establishing the conditions and a phonetic explanation for the development. All words that have thus far been proposed as instances of the *d > *h₁ change will be investigated more closely, leading to the conclusion that the Kortlandt effect is a type of debuccalisation due to dental dissimilation when *d is followed by a consonant. Typological parallels for this type of change, as well as evidence from IE daughter languages, enable us to identify it as a shift from pre-glottalised voiceless stop to glottal stop. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Alwin Kloekhorst for guiding me through the writing process, helping me along when I got stuck and for his general encouragement. I also want to thank the LUCL lecturers for sharing their knowledge all these years and helping me identify and research my own linguistic interests; my family for their love and support throughout this project; my friends – with a special mention of Bahuvrīhi: Laura, Lotte and Vera – and Martin, also for their love and support, for the good times in between writing and for being willing to give elaborate advice on even the smallest research issues. -

![A Sociophonetic Study of the Metropolitan French [R]: Linguistic Factors Determining Rhotic Variation a Senior Honors Thesis](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0716/a-sociophonetic-study-of-the-metropolitan-french-r-linguistic-factors-determining-rhotic-variation-a-senior-honors-thesis-970716.webp)

A Sociophonetic Study of the Metropolitan French [R]: Linguistic Factors Determining Rhotic Variation a Senior Honors Thesis

A Sociophonetic Study of the Metropolitan French [R]: Linguistic Factors Determining Rhotic Variation A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Sarah Elyse Little The Ohio State University June 2012 Project Advisor: Professor Rebeka Campos-Astorkiza, Department of Spanish and Portuguese ii ABSTRACT Rhotic consonants are subject to much variation in their production cross-linguistically. The Romance languages provide an excellent example of rhotic variation not only across but also within languages. This study explores rhotic production in French based on acoustic analysis and considerations of different conditioning factors for such variation. Focusing on trills, previous cross-linguistic studies have shown that these rhotic sounds are oftentimes weakened to fricative or approximant realizations. Furthermore, their voicing can also be subject to variation from voiced to voiceless. In line with these observations, descriptions of French show that its uvular rhotic, traditionally a uvular trill, can display all of these realizations across the different dialects. Focusing on Metropolitan French, i.e., the dialect spoken in Paris, Webb (2009) states that approximant realizations are preferred in coda, intervocalic and word-initial positions after resyllabification; fricatives are more common word-initially and in complex onsets; and voiceless realizations are favored before and after voiceless consonants, with voiced productions preferred elsewhere. However, Webb acknowledges that the precise realizations are subject to much variation and the previous observations are not always followed. Taking Webb’s description as a starting point, this study explores the idea that French rhotic production is subject to much variation but that such variation is conditioned by several factors, including internal and external variables. -

The Diachronic Emergence of Retroflex Segments in Three Languages* 1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hochschulschriftenserver - Universität Frankfurt am Main The diachronic emergence of retroflex segments in three languages* Silke Hamann ZAS (Centre for General Linguistics), Berlin [email protected] The present study shows that though retroflex segments can be considered articulatorily marked, there are perceptual reasons why languages introduce this class into their phoneme inventory. This observation is illustrated with the diachronic developments of retroflexes in Norwegian (North- Germanic), Nyawaygi (Australian) and Minto-Nenana (Athapaskan). The developments in these three languages are modelled in a perceptually oriented phonological theory, since traditional articulatorily-based features cannot deal with such processes. 1 Introduction Cross-linguistically, retroflexes occur relatively infrequently. From the 317 languages of the UPSI database (Maddieson 1984, 1986), only 8.5 % have a voiceless retroflex stop [ˇ], 7.3 % a voiced stop [Í], 5.3 % a voiceless retroflex fricative [ß], 0.9 % a voiced fricative [¸], and 5.9 % a retroflex nasal [˜]. Compared to other segmental classes that are considered infrequent, such as a palatal nasal [¯], which occurs in 33.7 % of the UPSID languages, and the uvular stop [q], which occurs in 14.8 % of the languages, the percentages for retroflexes are strikingly low. Furthermore, typically only large segment inventories have a retroflex class, i.e. at least another coronal segment (apical or laminal) is present, as in Sanskrit, Hindi, Norwegian, Swedish, and numerous Australian Aboriginal languages. Maddieson’s (1984) database includes only one exception to this general tendency, namely the Dravidian language Kota, which has a retroflex as its only coronal fricative. -

Phones and Phonemes

NLPA-Phon1 (4/10/07) © P. Coxhead, 2006 Page 1 Natural Language Processing & Applications Phones and Phonemes 1 Phonemes If we are to understand how speech might be generated or recognized by a computer, we need to study some of the underlying linguistic theory. The aim here is to UNDERSTAND the theory rather than memorize it. I’ve tried to reduce and simplify as much as possible without serious inaccuracy. Speech consists of sequences of sounds. The use of an instrument (such as a speech spectro- graph) shows that most of normal speech consists of continuous sounds, both within words and across word boundaries. Speakers of a language can easily dissect its continuous sounds into words. With more difficulty, they can split words into component sounds, or ‘segments’. However, it is not always clear where to stop splitting. In the word strip, for example, should the sound represented by the letters str be treated as a unit, be split into the two sounds represented by st and r, or be split into the three sounds represented by s, t and r? One approach to isolating component sounds is to look for ‘distinctive unit sounds’ or phonemes.1 For example, three phonemes can be distinguished in the word cat, corresponding to the letters c, a and t (but of course English spelling is notoriously non- phonemic so correspondence of phonemes and letters should not be expected). How do we know that these three are ‘distinctive unit sounds’ or phonemes of the English language? NOT from the sounds themselves. A speech spectrograph will not show a neat division of the sound of the word cat into three parts.