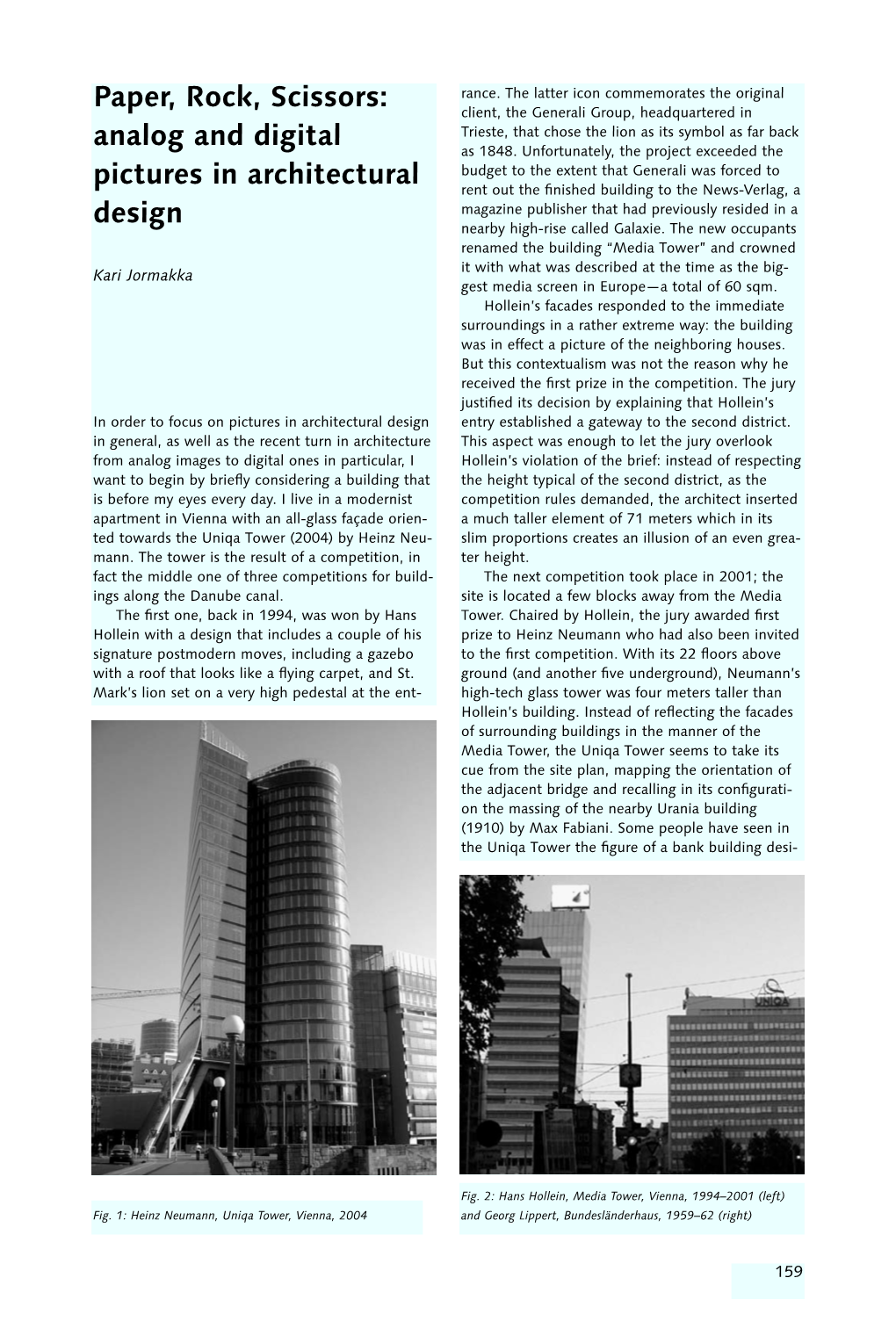

Paper, Rock, Scissors: Analog and Digital Pictures in Architectural Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canal Grande (The Grand Canal)

Canal Grande (The Grand Canal) Night shot of the Canal Grande or Grand Canal of Venice, Italy The Canal Grande and the Canale della Giudecca are the two most important waterways in Venice. They undoubtedly fall into the category of one of the premier tourist attractions in Venice. The Canal Grande separates Venice into two distinct parts, which were once popularly referred to as 'de citra' and 'de ultra' from the point of view of Saint Mark's Basilica, and these two parts of Venice are linked by the Rialto bridge. The Rialto Bridge is the most ancient bridge in Venice.; it is completely made of stone and its construction dates back to the 16th century. The Canal Grande or the Grand Canal forms one of the major water-traffic corridors in the beautiful city of Venice. The most popular mode of public transportation is traveling by the water bus and by private water taxis. This canal crisscrosses the entire city of Venice, and it begins its journey from the lagoon near the train station and resembles a large S-shape through the central districts of the "sestiere" in Venice, and then comes to an end at the Basilica di Santa Maria della Salute near the Piazza San Marco. The major portion of the traffic of the city of Venice goes along the Canal Grande, and thus to avoid congestion of traffic there are already three bridges – the Ponte dei Scalzi, the Ponte dell'Accademia, and the Rialto Bridge, while another bridge is being constructed. The new bridge is designed by Santiago Calatrava, and it will link the train station to the Piazzale Roma. -

Rodolfo Lanciani, the Ruins and Excavations of Ancient Rome, 1897, P

10/29/2010 1 Primus Adventus ad Romam Urbem Aeternam Your First Visit to Rome The Eternal City 2 Accessimus in Urbe AeternA! • Welcome, traveler! Avoiding the travails of the road, you arrived by ship at the port of Ostia; from there, you’ve had a short journey up the Via Ostiensis into Roma herself. What do you see there? 3 Quam pulchra est urbs aeterna! • What is there to see in Rome? • What are some monuments you have heard of? • How old are the buildings in Rome? • How long would it take you to see everything important? 4 Map of Roma 5 The Roman Forum • “According to the Roman legend, Romulus and Tatius, after the mediation of the Sabine women, met on the very spot where the battle had been fought, and made peace and an alliance. The spot, a low, damp, grassy field, exposed to the floods of the river Spinon, took the name of “Comitium” from the verb coire, to assemble. It is possible that, in consequence of the alliance, a road connecting the Sabine and the Roman settlements was made across these swamps; it became afterwards the Sacra Via…. 6 The Roman Forum • “…Tullus Hostilius, the third king, built a stone inclosure on the Comitium, for the meeting of the Senators, named from him Curia Hostilia; then came the state prison built by Ancus Marcius in one of the quarries (the Tullianum). The Tarquin [kings] drained the land, gave the Forum a regular (trapezoidal) shape, divided the space around its borders into building- lots, and sold them to private speculators for shops and houses, the fronts of which were to be lined with porticoes.” --Rodolfo Lanciani, The Ruins and Excavations of Ancient Rome, 1897, p. -

The Architecture of Roman Temples

P1: JzL 052181068XAgg.xml CB751B/Stamper 0 521 81068 X August 28, 2004 17:30 The Architecture of Roman Temples - The Republic to the Middle Empire John W. Stamper University of Notre Dame iii P1: JzL 052181068XAgg.xml CB751B/Stamper 0 521 81068 X August 28, 2004 17:30 published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C John W. Stamper 2005 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2005 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typefaces Bembo 11/14 pt., Weiss, Trajan, and Janson System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Stamper, John W. The architecture of Roman temples : the republic to the middle empire / John W. Stamper. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-521-81068-x 1. Temples, Roman – Italy – Rome. 2. Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus (Rome, Italy) 3. Architecture, Roman – Italy – Rome – Influence. 4. Rome (Italy) -

9781107013995 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01399-5 — Rome Rabun Taylor , Katherine Rinne , Spiro Kostof Index More Information INDEX abitato , 209 , 253 , 255 , 264 , 273 , 281 , 286 , 288 , cura(tor) aquarum (et Miniciae) , water 290 , 319 commission later merged with administration, ancient. See also Agrippa ; grain distribution authority, 40 , archives ; banishment and 47 , 97 , 113 , 115 , 116 – 17 , 124 . sequestration ; libraries ; maps ; See also Frontinus, Sextus Julius ; regions ( regiones ) ; taxes, tarif s, water supply ; aqueducts; etc. customs, and fees ; warehouses ; cura(tor) operum maximorum (commission of wharves monumental works), 162 Augustan reorganization of, 40 – 41 , cura(tor) riparum et alvei Tiberis (commission 47 – 48 of the Tiber), 51 censuses and public surveys, 19 , 24 , 82 , cura(tor) viarum (roads commission), 48 114 – 17 , 122 , 125 magistrates of the vici ( vicomagistri ), 48 , 91 codes, laws, and restrictions, 27 , 29 , 47 , Praetorian Prefect and Guard, 60 , 96 , 99 , 63 – 65 , 114 , 162 101 , 115 , 116 , 135 , 139 , 154 . See also against permanent theaters, 57 – 58 Castra Praetoria of burial, 37 , 117 – 20 , 128 , 154 , 187 urban prefect and prefecture, 76 , 116 , 124 , districts and boundaries, 41 , 45 , 49 , 135 , 139 , 163 , 166 , 171 67 – 69 , 116 , 128 . See also vigiles (i re brigade), 66 , 85 , 96 , 116 , pomerium ; regions ( regiones ) ; vici ; 122 , 124 Aurelian Wall ; Leonine Wall ; police and policing, 5 , 100 , 114 – 16 , 122 , wharves 144 , 171 grain, l our, or bread procurement and Severan reorganization of, 96 – 98 distribution, 27 , 89 , 96 – 100 , staf and minor oi cials, 48 , 91 , 116 , 126 , 175 , 215 102 , 115 , 117 , 124 , 166 , 171 , 177 , zones and zoning, 6 , 38 , 84 , 85 , 126 , 127 182 , 184 – 85 administration, medieval frumentationes , 46 , 97 charitable institutions, 158 , 169 , 179 – 87 , 191 , headquarters of administrative oi ces, 81 , 85 , 201 , 299 114 – 17 , 214 Church. -

Perspektiven Der Spolienforschung 2. Zentren Und Konjunkturen Der

Perspektiven der Spolienforschung Stefan Altekamp Carmen Marcks-Jacobs Peter Seiler (eds.) BERLIN STUDIES OF THE ANCIENT WORLD antiker Bauten, Bauteile und Skulpturen ist ein weitverbreite- tes Phänomen der Nachantike. Rom und der Maghreb liefern zahlreiche und vielfältige Beispiele für diese An- eignung materieller Hinterlassenscha en der Antike. Während sich die beiden Regionen seit dem Ausgang der Antike politisch und kulturell sehr unterschiedlich entwickeln, zeigen sie in der praktischen Umsetzung der Wiederverwendung, die zwischenzeitlich quasi- indus trielle Ausmaße annimmt, strukturell ähnliche orga nisatorische, logistische und rechtlich-lenkende Praktiken. An beiden Schauplätzen kann die Antike alternativ als eigene oder fremde Vergangenheit kon- struiert und die Praxis der Wiederverwendung utili- taristischen oder ostentativen Charakter besitzen. 40 · 40 Perspektiven der Spolien- forschung Stefan Altekamp Carmen Marcks-Jacobs Peter Seiler Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © Edition Topoi / Exzellenzcluster Topoi der Freien Universität Berlin und der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Abbildung Umschlag: Straßenkreuzung in Tripolis, Photo: Stefan Altekamp Typographisches Konzept und Einbandgestaltung: Stephan Fiedler Printed and distributed by PRO BUSINESS digital printing Deutschland GmbH, Berlin ISBN ---- URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:- First published Published under Creative Commons Licence CC BY-NC . DE. For the terms of use of the illustrations, please see the reference lists. www.edition-topoi.org INHALT , -, Einleitung — 7 Commerce de Marbre et Remploi dans les Monuments de L’Ifriqiya Médiévale — 15 Reuse and Redistribution of Latin Inscriptions on Stone in Post-Roman North-Africa — 43 Pulcherrima Spolia in the Architecture and Urban Space at Tripoli — 67 Adding a Layer. -

V. MOSCHINI Spetto Del Quadro, Quando La Pulitura, Iniziata Con Piccole Prove Che Trovarono Ampia Conferma Nelle Radiografie, I) V

©Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo -Bollettino d'Arte FIG. I - VENEZIA, GALLERIE DELL' ACCADEMIA - LA PRIMA SALA NUOVI ALLESTIMENTI E RESTAURI di Venezia poter contare su di un artista come Carlo Scarpa, dotato di una sensibilità più che rara, anche se ALLE GALLERIE DI VENEZIA egli talvolta trovò delle limitazioni, specialmente dovute all'edificio già esistente. Le rettifiche durante i lavori A QUANDO NEL 1948 davo notizia in questo Bollettino furono appena quelle inevitabili in simili operazioni, nè vi D della nuova sistemazione in corso delle Gallerie del furono esperimenti magari audaci ma con il rischio di l'Accademia, I) non poco si è fatto per presentare in modo dover rifare tutto daccapo. Vi potranno essere dei ritocchi, organico e omogeneo il nucleo essenziale di quella ecce ma l'insieme sembra destinato a restare almeno per la zionale raccolta, anche se siamo stati costretti a lasciar durata normale di tali allestimenti, e questo è già qualcosa. da parte i progetti di ampliamento. Nel frattempo alcuni Dopo i primi lavori, tra i quali fu specialmente dimostra lavori vennero fatti conoscere,2) ma sia pure a costo di tiva la sistemazione della sala di S. Orsola, si passò a uti ripetizioni non sarà forse inutile qualche cenno ulteriore. lizzare il vasto e disorganico ambiente costituito dalla parte I criteri indicati in quel mio articolo ormai stagionato superiore della Chiesa della Carità, reso anzitutto assai più vennero seguiti successivamente con quella fedeltà che era luminoso per l'apertura di nuovi lucernai. S'introdusse solo possibile restando le persone che continuavano ad at qui in pieno l'uso di pannelli anche di grandI dimensioni, tuarli. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02320-8 - Campus Martius: The Field of Mars in the Life of Ancient Rome Paul W. Jacobs II and Diane Atnally Conlin Frontmatter More information CAMPUS MARTIUS A mosquito-infested and swampy plain lying north of the city walls, Rome’s Campus Martius, or Field of Mars, was used for much of the Roman Republic as a military training ground and as a site for celebratory rituals and the occasional political assembly. Initially punctuated with temples vowed by victorious generals, during the imperial era it became filled with extraordinary baths, theaters, porticoes, aqueducts, and other structures – many of which were architectural firsts for the capital. This book explores the myriad factors that contributed to the transformation of the Campus Martius from an occasionally visited space to a crowded center of daily activity. It presents a case study of the repurposing of urban landscape in the Roman world and explores how existing topographical features that fit well with the republic’s needs ultimately attracted architecture that forever transformed those features but still resonated with the area’s original military and ceremonial traditions. Paul W. Jacobs II is an independent scholar who focuses on ancient Rome and its topographical development. A graduate of Harvard College and the University of Virginia Law School, and a litigator by training, Jacobs has practiced and published in the area of voting rights, where knowledge of demographics, mapmaking, and geography is essential. He has spent extensive time in Rome and has studied the ancient city and its development for decades. Diane Atnally Conlin is Associate Professor of Classics at the University of Colorado, Boulder. -

Precincts of Venus: Towards a Prehistory of Ovidian Genre Joseph Farrell University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Classical Studies) Classical Studies at Penn 2005 Precincts of Venus: Towards a Prehistory of Ovidian Genre Joseph Farrell University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Farrell, J. (2005). Precincts of Venus: Towards a Prehistory of Ovidian Genre. Hermathena, 177/178 27-69. Retrieved from http://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/158 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/158 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Precincts of Venus: Towards a Prehistory of Ovidian Genre Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Classics This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: http://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/158 Precincts of Venus: towards a prehistory of Ovidian genre by Joseph Farrell 1. Introduction One of the characteristically Ovidian themes in contemporary Latin studies is the plasticity of genre and the inventiveness with which Roman poets address generic concerns. Coming to terms with this problem has greatly advanced recent work on Latin poetry. In particular, our heightened ability to appreciate the shimmering ambiguity of Ovidian genre has led to a much more productive model for practising the hermeneutics of indeterminacy than had been current in Latin studies. Another recent gain has been an increased understanding of Ovidian genre in its historical -

Building in Early Medieval Rome, 500-1000 AD

BUILDING IN EARLY MEDIEVAL ROME, 500 - 1000 AD Robert Coates-Stephens PhD, Archaeology Institute of Archaeology, University College London ProQuest Number: 10017236 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10017236 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract The thesis concerns the organisation and typology of building construction in Rome during the period 500 - 1000 AD. Part 1 - the organisation - contains three chapters on: ( 1) the finance and administration of building; ( 2 ) the materials of construction; and (3) the workforce (including here architects and architectural tracts). Part 2 - the typology - again contains three chapters on: ( 1) ecclesiastical architecture; ( 2 ) fortifications and aqueducts; and (3) domestic architecture. Using textual sources from the period (papal registers, property deeds, technical tracts and historical works), archaeological data from the Renaissance to the present day, and much new archaeological survey-work carried out in Rome and the surrounding country, I have outlined a new model for the development of architecture in the period. This emphasises the periods directly preceding and succeeding the age of the so-called "Carolingian Renaissance", pointing out new evidence for the architectural activity in these supposed dark ages. -

Forma Urbis Romae) Elizabeth Wolfram Thill

A Cunning Plan: Interpreting the Inscriptions of the Severan Marble Plan (Forma Urbis Romae) Elizabeth Wolfram Thill Paper presented at 119th Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America, Boston, MA, 4-7 January, 2018 [Slide 1] The Forma Urbis Romae is one of the most unique monuments in Roman art. Set up on display in the heart of the city, it was a gigantic marble map of the city of Rome. Its two most notable features were its size—it was over four stories tall—and its apparent inclusion of every building in the city, from the Circus Maximus to one-room apartments. [2] The monument represents the city in plan form with incredible detail. Sidewalks, doorways, even interior staircases are shown for great buildings and humble dwellings alike. Columns decorate temples and private houses. Fountains and neighborhood shrines crowd the streets. Amphitheaters, warehouses, apartments, temples, basilicae, baths, houses, shops and more mingle together to present the city of Rome as a tableau of diverse and unremitting architecture. [3] Since the Forma’s rediscovery in 1562, scholars have been most excited for the monument’s potential to aid in the mapping and reconstruction of the ancient city and its buildings. Handily for those interested in such pursuits, many of the features of the Forma are labeled with neat inscriptions. An obvious but so far unexplored question springs to mind: why were some buildings labeled and others not? I will present here my preliminary results from my efforts to answer this basic question. I will argue that structures apparently are not labeled according to location or chronology, whether they are public or private, or whether they are otherwise identifiable. -

Venice & the Veneto

Plan Your Trip 1 ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Venice & the Veneto “All you’ve got to do is decide to go and the hardest part is over. So go!” TONY WHEELER, COFOUNDER – LONELY PLANET THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Cristian Bonetto, Paula Hardy Contents PlanPlan Your Your Trip Trip page 1 4 Welcome to Venice & the If You Like... ������������������� 18 Eating ���������������������������27 Veneto ������������������������������ 4 Month by Month ������������20 Drinking & Nightlife ���33 Venice’s Top 10 ���������������� 6 For Free ��������������������������22 Entertainment �������������37 What’s New �������������������� 13 With Kids ������������������������23 Shopping ����������������������41 Need to Know �����������������14 Tours �������������������������������25 Top Itineraries ����������������16 Explore Venice & the Veneto 44 Neighbourhoods at a San Polo & Murano, Burano & the Glance ����������������������������46 Santa Croce �������������������84 Northern Islands ����������147 San Marco ����������������������48 Cannaregio ������������������ 105 Day Trips from Dorsoduro �����������������������71 Castello �������������������������117 Venice �������������������������160 Giudecca, Lido & the Sleeping ���������������������186 Southern Islands ��������� 136 Understand Venice & the Veneto 199 Venice Today �������������� 200 Architecture ����������������� 215 The Fragile Lagoon �����237 History ��������������������������202 The Arts������������������������225 Survival Guide 239 Transport �������������������� 240 Language ���������������������252 -

The Thin White Line: Palladio, White Cities and the Adriatic Imagination

Chapter � The Thin White Line: Palladio, White Cities and the Adriatic Imagination Alina Payne Over the course of centuries, artists and architects have employed a variety of means to capture resonant archaeological sites in images, and those images have operated in various ways. Whether recording views, monuments, inscrip- tions, or measurements so as to pore over them when they came home and to share them with others, these draftsmen filled loose sheets, albums, sketch- books, and heavily illustrated treatises and disseminated visual information far and wide, from Europe to the margins of the known world, as far as Mexico and Goa. Not all the images they produced were factual and aimed at design and construction. Rather, they ranged from reportage (recording what there is) through nostalgic and even fantastic representations to analytical records that sought to look through the fragmentary appearance of ruined vestiges to the “essence” of the remains and reconstruct a plausible original form. Although this is a long and varied tradition and has not lacked attention at the hands of generations of scholars,1 it raises an issue fundamental for the larger questions that are posed in this essay: Were we to look at these images as images rather than architectural or topographical information, might they emerge as more than representations of buildings, details and sites, measured and dissected on the page? Might they also record something else, something more ineffable, such as the physical encounters with and aesthetic experience of these places, elliptical yet powerful for being less overt than the bits of carved stone painstakingly delineated? Furthermore, might in some cases the very material support of these images participate in translating this aesthetic 1 For Italian material the list is long.