Interim Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Honourable Sir Peter Cosgrove AK AC(MIL) CVO MC (Retd)

The Honourable Sir Peter Cosgrove AK AC(MIL) CVO MC (Retd) Australian Statesman, Keynote Speaker General the Honourable Sir Peter Cosgrove AK AC(Mil) CVO MC (Retd) is known as ‘a man of the people’. When recognised in 2001 as Australian of the Year, it was said that, “In every respect Peter Cosgrove demonstrated that he is a role model. The man at the top displayed those characteristics we value most as Australians – strength, determination, intelligence, compassion and humour.” Having led troops as a junior leader and as Commander-in-Chief, having served as Australia’s Governor General from 2014 to 2019, and having travelled the world and Australia, General the Honourable Sir Peter Cosgrove has unique perspectives on Australia, Australians and our place in the world. His views on leadership are grounded in experience, his keynotes are insightful, entertaining and revealing. More about General the Honourable Sir Peter Cosgrove: The son of a soldier, Peter Cosgrove attended Waverley College in Sydney and later graduated from the Royal Military College, Duntroon, in 1968. He was sent to Malaysia as a lieutenant in the 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment. During his next infantry posting in Vietnam he commanded a rifle platoon and was awarded the Military Cross for his performance and leadership during an assault on enemy positions. With his wife Lynne, the next twenty years saw the family grow to three sons and a wide variety of defence force postings, including extended duty in the UK and India. In 1999 Peter Cosgrove became a national figure following his appointment as Commander of the International Force East Timor (INTERFET). -

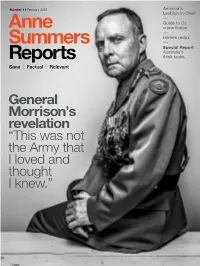

2015 Anne Summers Issue 11 2015

Number 11 February 2015 America’s Lesbian-in-Chief Guide to Oz crime fiction Harlem redux Special Report Australia’s think tanks Sane Factual Relevant General Morrison’s revelation “This was not the Army that I loved and thought I knew.” #11 February 2015 I HOPE YOU ENJOY our first issue for 2015, and our eleventh since we started our digital voyage just over two years ago. We introduce Explore, a new section dealing with ideas, science, social issues and movements, and travel, a topic many of you said, via our readers’ survey late last year, you wanted us to cover. (Read the full results of the survey on page 85.) I am so pleased to be able to welcome to our pages the exceptional mrandmrsamos, the husband-and-wife team of writer Lee Tulloch and photographer Tony Amos, whose piece on the Harlem revival is just a taste of the treats that lie ahead. No ordinary travel writing, I can assure you. Anne Summers We are very proud to publish our first investigative special EDITOR & PUBLISHER report on Australia’s think tanks. Who are they? Who runs them? Who funds them? How accountable are they and how Stephen Clark much influence do they really have? In this landmark piece ART DIRECTOR of reporting, Robert Milliken uncovers how thinks tanks are Foong Ling Kong increasingly setting the agenda for the government. MANAGING EDITOR In other reports, you will meet Merryn Johns, the Australian woman making a splash as a magazine editor Wendy Farley in New York and who happens to be known as America’s Get Anne Summers DESIGNER Lesbian-in-Chief. -

Hope for the Future for I Know the Plans I Have for You,” Declares the Lord, “Plans to Prosper You and Not to Harm You, Plans to Give You Hope and a Future

ISSUE 3 {2017} BRINGING THE LIGHT OF CHRIST INTO COMMUNITIES Hope for the future For I know the plans I have for you,” declares the Lord, “plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future Jeremiah 29:11 Lifting their voices What it’s like in their world Our first Children and Youth A new product enables participants Advocate will be responsible to experience the physical and for giving children and young mental challenges faced by people people a greater voice. living with dementia. networking ׀ 1 When Jesus spoke again to the people, he said, I am the light of the world. Contents Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness, but will have the light of life. John 8:12 (NIV) 18 9 20 30 8 15 24 39 From the Editor 4 Zillmere celebrates 135 years 16 Research paves way for better care 30 networking Churches of Christ in Queensland Chief Executive Officer update 5 Kenmore Campus - ready for the future 17 Annual Centrifuge conference round up 31 41 Brookfield Road Kenmore Qld 4069 PO Box 508 Kenmore Qld 4069 Spiritual Mentoring: Companioning Souls 7 Hope for future managers 19 After the beginnings 32 07 3327 1600 [email protected] Church of the Outback 8 Celebrating the first Australians 20 Gidgee’s enterprising ways 33 networking contains a variety of news and stories from Donations continue life of mission 9 Young, vulnerable and marginalised 22 People and Events 34 across Churches of Christ in Queensland. Articles and photos can be submitted to [email protected]. -

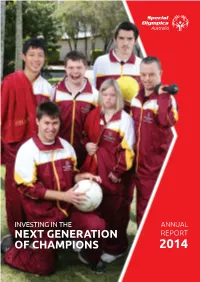

2014 Annual Report

Australia INVESTING IN THE ANNUAL NEXT GENERATION REPORT OF CHAMPIONS 2014 SPECIAL OLYMPICS AUSTRALIA CONTENTS ABOUT US 03 About Us Through a network of dedicated volunteers, 04 Joy! 06 Messages Special Olympics Australia brings the benefits 08 2014 Highlights of weekly sports training, coaching and competition 09 2015 Focus to people with an intellectual disability. 10 Athletes 12 Spotlight on National Games 16 Membership 18 Stakeholders 20 Excellence 22 Around Australia Global Movement, Local Impact The Facts 24 Working Together Special Olympics Australia is part of a global movement • People with an intellectual disability are 26 Financial Summary that began in the 1960s when Eunice Kennedy Shriver the largest disability population in the world.* 27 Team Australia invited 75 children with an intellectual disability to play • Over 500,000 Australians have an sport in her backyard. intellectual disability.** This Annual Report Today, Special Olympics support 4.4 million athletes • Every two hours an Australian child is This Annual Report covers the activities of Special in over 170 countries. diagnosed with an intellectual disability.*** Olympics Australia from 1 January - 31 December 2014. Charitable Status Special Olympics Inc. is the international governing Impact body of the Special Olympics movement, which Special Olympics Australia is a national charity One of the many barriers to success that people establishes all official policies and owns the registered with tax-exempt and deductible gift-recipient with an intellectual disability face is a negative trademarks to the Special Olympics name, logo and status granted by the Australian Tax Office. perception of what they can achieve. Our logo other intellectual property. -

Annual Report 2019 Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 CONTENTS PAGE PRESIDENT'S REVIEW 8 CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER’S REPORT 12 AUSTRALIAN OLYMPIC COMMITTEE 20 OLYMPISM IN THE COMMUNITY 26 OLYMPIAN SERVICES 38 TEAMS 46 ATHLETE AND NATIONAL FEDERATION FUNDING 56 FUNDING THE AUSTRALIAN OLYMPIC MOVEMENT 60 AUSTRALIA’S OLYMPIC PARTNERS 62 AUSTRALIA’S OLYMPIC HISTORY 66 CULTURE AND GOVERNANCE 76 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 88 AOF 2019 ANNUAL REPORT 119 CHAIR'S REVIEW 121 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 128 Australian Olympic Committee Incorporated ABN 33 052 258 241 REG No. A0004778J Level 4, Museum of Contemporary Art 140 George Street, Sydney, NSW 2000 P: +61 2 9247 2000 @AUSOlympicTeam olympics.com.au Photos used in this report are courtesy of Australian Olympic Team Supplier Getty Images. 3 OUR ROLE PROVIDE ATHLETES THE OPPORTUNITY TO EXCEL AT THE OLYMPIC GAMES AND PROMOTE THE VALUES OF OLYMPISM AND BENEFITS OF PARTICIPATION IN SPORT TO ALL AUSTRALIANS. 4 5 HIGHLIGHTS REGIONAL GAMES PARTNERSHIPS OLYMPISM IN THE COMMUNITY PACIFIC GAMES ANOC WORLD BEACH GAMES APIA, SAMOA DOHA, QATAR 7 - 20 JULY 2019 12 - 16 OCTOBER 2019 31PARTNERS 450 SUBMISSIONS 792 COMPLETED VISITS 1,022 11SUPPLIERS STUDENT LEADERS QLD 115,244 FROM EVERY STATE STUDENTS VISITED AND TERRITORY SA NSW ATHLETES55 SPORTS6 ATHLETES40 SPORTS7 ACT 1,016 26 SCHOOL SELECTED TO ATTEND REGISTRATIONS 33 9 14 1 4LICENSEES THE NATIONAL SUMMIT DIGITAL OLYMPIAN SERVICES ATHLETE CONTENT SERIES 70% 11,160 FROM FOLLOWERS Athlete-led content captured 2018 at processing sessions around 166% #OlympicTakeOver #GiveThatAGold 3,200 Australia, in content series to be 463,975 FROM OLYMPIANS published as part of selection IMPRESSIONS 2018 Campaign to promote Olympic CONTACTED announcements. -

THE COMMONWEALTH of AUSTRALIA TASMANIA Hobart Information About Australia

Darwin INDIAN OCEAN PACIFIC OCEAN NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND WESTERN AUSTRALIA Brisbane SOUTH AUSTRALIA NEW SOUTH Perth WALES Sydney Adelaïde CANBERRA VICTORIA INDIAN OCEAN Melbourne THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA TASMANIA Hobart Information about Australia This document is the map of Australia. It is an island bordered by the Indian Ocean in the west and the Pacific Ocean in the east. It is composed of eight territories, including the Australian Capital Territory though it is only a city. At the west of Australia, there is Western Australia. At the north east of Western Australia is the Northern Territory. At the east of Northern Territory, there is Queensland. The capital of New South Wales is Sydney. As for the legend of the map, blue is for the oceans, black represents territories and red stands for the capital city. There are about 23.5 (Twenty-three point five) million inhabitants in Australia. Australia’s area is about 7, 686,850 (seven million six hundred and eighty-six thousand eight hundred and fifty) square kilometres. Though it is not the largest city in the country with only 360,000 inhabitants, Canberra is Australia's capital city. Indeed it was a compromise between Sydney and Melbourne which are the most populated cities of Australia with respectively 4.7 and 4.3 million inhabitants. Melbourne is the second largest Australian city with 4.3 (four point three) million inhabitants. The biggest cities are all on the East Coast, also nicknamed/called the Gold Coast except for Perth, which is on the West Coast. James Cook was the first British explorer in 1770 (seventeen seventy). -

1 Army in the 21 Century and Restructuring the Army: A

Army in the 21st Century and Restructuring the Army: A Retrospective Appraisal of Australian Military Change Management in the 1990s Renée Louise Kidson July 2016 A sub-thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Military and Defence Studies (Advanced) of The Australian National University © Copyright by Renée Louise Kidson 2016 All Rights Reserved 1 Declaration This sub-thesis is my own original work. I declare no part of this work has been: • copied from any other person's work except where due acknowledgement is made in the text; written by any other person; or • submitted for assessment in another course. The sub-thesis word count is 16,483 excluding Table of Contents, Annexes and Chapter 2 (Literature Review and Methods, a separate assessment under the MMDS(Adv) program). Renee Kidson Acknowledgements I owe my greatest thanks to my supervisors: Dr John Blaxland (ANU) and Colonel David Connery (Australian Army History Unit, AAHU), for wise counsel, patience and encouragement. Dr Roger Lee (Head, AAHU) provided funding support; and, crucially, a rigorous declassification process to make select material available for this work. Lieutenant Colonel Bill Houston gave up entire weekends to provide my access to secure archival vault facilities. Meegan Ablett and the team at the Australian Defence College Vale Green Library provided extensive bibliographic support over three years. Thanks are also extended to my interviewees: for the generosity of their time; the frankness of their views; their trust in disclosing materially relevant details to me; and for providing me with perhaps the finest military education of all – insights to the decision-making processes of senior leaders: military and civilian. -

EABC Business Mission to Europe 2018 Mission Report

EABC Business Mission to Europe 2018 Supported by EABC Major Partners: Paris, Strasbourg, Madrid, Lisbon & London 1 July - 10 July 2018 Mission Report (Executive Summary) Overview The EABC Business Mission to Europe is undertaken each year as an initiative to strengthen bilateral relationships with European leaders, institutions, officials, peak business groups and policy organisations. The missions travel to Brussels as the political and administrative capital of the European Union (EU), and to other political and commercial capitals in Europe. Since 2006, EABC delegations have travelled to Amsterdam, Antwerp, Berlin, Bern, Bratislava, Budapest, Copenhagen, Dublin, Frankfurt, Geneva, Hamburg, Helsinki, Istanbul, Lisbon, London, Madrid, Milan, Munich, Paris, Rotterdam, Stockholm, Strasbourg, The Hague, Toulouse, Venice, Vienna, Warsaw and Zurich. During the missions, delegates have met with the European Commission President, Vice- Presidents and Commissioners, Vice-Presidents of the European Parliament and chairs of parliamentary committees, the Deputy President of the European Central Bank, Heads of State and Heads of Government, Ministers, central bankers, and leaders of peak employer and industry groups across Europe. The visits provide opportunities for senior Australian business representatives to engage in dialogue on key developments occurring at the EU and Member State levels in strategic areas including political and economic governance, banking and financial services regulation, trade policy and negotiations, research and innovation, energy and climate change, foreign and security policy, competition policy, transport and mobility, infrastructure and many others. The missions also provide a valuable opportunity for Australian business to engage with Australian Government representatives in Europe - principally with Australian Embassies and Austrade offices - to profile Australia’s economic credentials and capabilities. -

ANNUAL REPORT LUNG FOUNDATION AUSTRALIA 2016 Lung Foundation Australia |

Victoria Taber, six year survivor of lung cancer and her son, Archie. ANNUAL REPORT LUNG FOUNDATION AUSTRALIA 2016 Lung Foundation Australia | www.lungfoundation.com.au Contents 1 Making an impact 2 Message from the Chair and CEO 4 The facts 5 Who we are 6 Patient and community support 8 Clinical support 10 Research 12 Advocacy and awareness 14 Fundraising 16 Celebrating our people 17 Meet our leaders 18 Meet our board 20 Thank you, corporate partners and sponsors 21 Collaboration 23 Summary financial statement 24 Financials Lung Foundation Australia PO Box 1949 Milton, Queensland, 4064 1800 654 301 [email protected] www.lungfoundation.com.au ANNUAL REPORT Making an impact COMMUNITY AND AWARENESS KEY ACHIEVEMENTS PATIENT SUPPORT S CLINICAL SUPPORT PAGES VIEWED PAGE 1 Lung Foundation Australia | Annual Report 2016 Message from the Chair and CEO Lung disease, including thoracic cancers and chronic respiratory Throughout the year, we continued to focus on improving diseases, remains the second leading cause of death in Australia the outcome and quality of life for those living with lung after ischaemic heart disease1. It affects approximately one in disease through the provision of evidence-based services four Australians2 and is responsible for more than 10% of and support. Australia’s overall health burden3. Highlights Despite this, publicity, empathy, research and funding for lung Research: Lung disease struggles to attract the same level diseases in Australia remain extremely low. Lung disease has of research funding received by other disease areas. Lung never been a simple issue and it is our belief that widespread Foundation Australia works tirelessly to help fill this gap, with negative attitudes and social stigma surrounding those with support for research remaining one of our critical priorities. -

Part 4 Australia Today

Australia today In these pages you will learn about what makes this country so special. You will find out more about our culture, Part 4 our innovators and our national identity. In the world today, Australia is a dynamic business and trade partner and a respected global citizen. We value the contribution of new migrants to our country’s constant growth and renewal. Australia today The land Australia is unique in many ways. Of the world’s seven continents, Australia is the only one to be occupied by a single nation. We have the lowest population density in the world, with only two people per square kilometre. Australia is one of the world’s oldest land masses. It is the sixth largest country in the world. It is also the driest inhabited continent, so in most parts of Australia water is a very precious resource. Much of the land has poor soil, with only 6 per cent suitable for agriculture. The dry inland areas are called ‘the Australia is one of the world’s oldest land masses. outback’. There is great respect for people who live and work in these remote and harsh environments. Many of It is the sixth largest country in the world. them have become part of Australian folklore. Because Australia is such a large country, the climate varies in different parts of the continent. There are tropical regions in the north of Australia and deserts in the centre. Further south, the temperatures can change from cool winters with mountain snow, to heatwaves in summer. In addition to the six states and two mainland territories, the Australian Government also administers, as territories, Ashmore and Cartier Islands, Christmas Island, the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Jervis Bay Territory, the Coral Sea Islands, Heard Island and McDonald Islands in the Australian Antarctic Territory, and Norfolk Island. -

Introduction

Introduction In his third Boyer Lecture of November 2009, General Peter Cosgrove, the former Chief of the Australian Defence Force, noted several points on the subject of ‘Leading in Australia’, based on his own forty years of military experience. It was ‘a universal truth’, he said, that leaders ‘are accountable’. ‘Leaders who fail to appreciate this fundamental precept of accountability must also fail to muster the profound commitment true leadership demands’. Furthermore, leadership required a keen understanding of the nature of teamwork, and of the fact that ‘teamwork is adversarial’, whether the team be pitted against another, against the environment or against the standards that the team has set itself. The key to successful leadership is ‘to simply and clearly identify the adversary to the team’ and to overcome the team’s or one’s own shortcomings to forge a cohesive unit united against the adversary. Finally, a leader must be an effective communicator. ‘Communication is the conduit of leadership’, and ‘Leadership uncommunicated is leadership unrequited’. ‘Leadership messages must be direct, simple, [and] fundamentally relevant to each member of the team’.1 While Cosgrove was speaking broadly of contemporary leadership in the military, government and business, his general statements were as applicable to the late eighteenth century as they are today. This thesis examines the subject of leadership in the colony of New South Wales (NSW) for the period 1788 to 1794. The two principal leaders for that period were Captain Arthur Phillip R.N. and Major Francis Grose, the commandant of the New South Wales Corps who assumed command of the colony on Phillip’s departure in December 1792. -

2014 05 23 E-News Vol 1 No 16

OKGA E-News 23 rd May 2014 Vol. 1 No. 16 TWO GENERALS VISIT KNOX IN A WEEK! Governor- General Visits Knox Australia’s new Governor-General, His Excellency General the Honourable Sir Peter Cosgrove AK MC (Ret’d) visited Knox yesterday to give the Address at the Sir John Monash Commemorative Service in the Great Hall, on behalf of The Spirit of Australia Foundation . The Foundation was established to remember and commemorate Australia’s heritage. Its aims are to educate Australian’s, especially school students, about the great Australian role models who have made a significant contribution to our country in a variety of endeavours, and to remember and commemorate Significant Australian’s and events. Students from many other schools around Sydney joined with the boys and cadet unit of Knox, in a packed Great Hall. The Knox Honour Guard, Catafalque Party, Pipes & Drums, the Bugler, Speakers and the Knox Symphonic Wind Ensemble & Combined Choirs all performed magnificently, and received high praise from the Official Party and guests. The Governor-General is welcomed by Headmaster John Weeks The Governor-General takes the salute from the Honour Guard. Standing behind the G-G is Headmaster, John Weeks (right) and Chairman of Council, Peter Roach (OKG’79)(hands clasped) General Sir Peter Cosgrove inspects the Guard of Honour. Inspecting the Pipes & Drums Guests depart the Great Hall after the Ceremony .The Knox Symphonic Wind Ensemble in the background ANZAC Memorial Service for the Old Knox Grammarians Association and Ceremonial Parade of the Knox Grammar Cadet Unit On an unseasonably warm morning last Sunday, the OKGA Memorial ANZAC Service was held at the School.