1 Army in the 21 Century and Restructuring the Army: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radical Islamist Groups in the Modern Age

WORKING PAPER NO. 376 RADICAL ISLAMIST GROUPS IN THE MODERN AGE: A CASE STUDY OF HIZBULLAH Lieutenant-Colonel Rodger Shanahan Canberra June 2003 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Shanahan, Rodger, 1964-. Radical Islamist Groups in the Modern Age: A Case Study of Hizbullah Bibliography. ISBN 0 7315 5435 3. 1. Hizballah (Lebanon). 2. Islamic fundamentalism - Lebanon. 3. Islam and politics - Lebanon. 4. Terrorism - Religious aspects - Islam. I. Title. (Series : Working paper (Australian National University. Strategic and Defence Studies Centre) ; no.376). 322.42095692 Strategic and Defence Studies Centre The aim of the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, which is located in the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies in the Australian National University, is to advance the study of strategic problems, especially those relating to the general region of Asia and the Pacific. The centre gives particular attention to Australia’s strategic neighbourhood of Southeast Asia and the Southwest Pacific. Participation in the centre’s activities is not limited to members of the university, but includes other interested professional, diplomatic and parliamentary groups. Research includes military, political, economic, scientific and technological aspects of strategic developments. Strategy, for the purpose of the centre, is defined in the broadest sense of embracing not only the control and application of military force, but also the peaceful settlement of disputes that could cause violence. This is the leading academic body in Australia specialising in these studies. Centre members give frequent lectures and seminars for other departments within the ANU and other universities and Australian service training institutions are heavily dependent upon SDSC assistance with the strategic studies sections of their courses. -

Australian Journal of Emergency Management

Department of Home Affairs Australian Journal of Emergency Management VOLUME 36 NO. 1 JANUARY 2021 ISSN: 1324 1540 NEWS AND VIEWS REPORTS RESEARCH Forcasting and Using community voice Forecasting the impacts warnings to build a new national of severe weather warnings system Pages 11 – 21 Page 50 Page 76 SUPPORTING A DISASTER RESILIENT AUSTRALIA Changes to forcasting and warnings systems improve risk reduction About the journal Circulation The Australian Journal of Emergency Management is Australia’s Approximate circulation (print and electronic): 5500. premier journal in emergency management. Its format and content are developed with reference to peak emergency management Copyright organisations and the emergency management sectors—nationally and internationally. The journal focuses on both the academic Articles in the Australian Journal of Emergency Management are and practitioner reader. Its aim is to strengthen capabilities in the provided under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial sector by documenting, growing and disseminating an emergency (CC BY-NC 4.0) licence that allows reuse subject only to the use management body of knowledge. The journal strongly supports being non-commercial and to the article being fully attributed the role of the Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience as a (creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0). national centre of excellence for knowledge and skills development © Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience 2021. in the emergency management sector. Papers are published in Permissions information for use of AJEM content all areas of emergency management. The journal encourages can be found at http://knowledge.aidr.org.au/ajem empirical reports but may include specialised theoretical, methodological, case study and review papers and opinion pieces. -

Interim Report

Interim Report Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry VOLUME 1 i © Commonwealth of Australia 2018 ISBN: 978-1-920838-50-8 (print) 978-1-920838-51-5 (online) With the exception of the Coat of Arms and where otherwise stated, all material presented in this publication is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (www.creativecommons.org/licenses). For the avoidance of doubt, this means this licence only applies to material as set out in this document. The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website as is the full legal code for the CC BY 4.0 licence (www.creativecommons.org/licenses). Use of the Coat of Arms The terms under which the Coat of Arms can be used are detailed on the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet website (www.dpmc.gov.au/government/commonwealth-coat-arms) Letter of Transmittal 28 September 2018 His Excellency General the Honourable Sir Peter Cosgrove AK MC (Retd) Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia Government House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Your Excellency In accordance with the Letters Patent issued to me on 14 December 2017, I have made inquiries and prepared an Interim Report of the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry. Yours sincerely [Signed] Kenneth M Hayne Commissioner iii Contents Volume 1 Executive summary xix Glossary xxi Abbreviations xxv Legislation xxvii 1. Introduction 1 1 Establishment 4 2 The first steps 6 3 Initial inquiries 7 4 Public engagement 10 5 Proceeding by case study 12 6 Work outside hearings 14 6.1 Research 14 6.2 Public engagement 16 6.3 Choosing case studies 17 6.4 Moving targets 17 v Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry 2. -

New Zealand) the Chief of Defence Force (CDF

Chief of Defence Force (New Zealand) The Chief of Defence Force (CDF) is the appointment held by the professional head of the New Zealand Defence Force. The post has existed under its present name since 1991. From 1963 to 1991 the head of the New Zealand Defence Force was known as the Chief of Defence Staff. All the incumbents have held three-star rank. Current Chief of Defence Force Tim Keating (soldier) Lieutenant General Tim Keating, MNZM is a New Zealand Army officer and the current Chief of the New Zealand Defence Force. He was appointed to this position immediately following his tenure as Vice Chief of Defence Force. He served as Chief of Army from 2011 to 2012. Keating was promoted to lieutenant general and took over as Chief of Defence Force for a three-year term on 1 February 2014. Career highlights January 1982: enlisted into the New Zealand Army as an Officer Cadet December 1982: joined the Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment upon graduation from the Officer Cadet School in Waiouru January 1985: Second-in-Command of a Rifle Company, 2nd/1st Battalion June 1986: posted to New Zealand Special Air Service Group December 1988: promoted to the rank of Captain December 1990: returned to NZSAS Group and was appointed Officer Commanding A Squadron 1996: completed the Australian Command and Staff Course in Queenscliff October 1997: posted on promotion as the Commanding Officer of the New Zealand contingent to the Multinational Force in the Sinai Peninsula January 1999: Commanding Officer, 1 NZSAS Group December 2001: Commandant, Officer -

Darwin 5 • New Accessions – Alice Springs 6 • Spotlight on

June 2005 No.29 ISSN 1039 - 5180 From the Director NT History Grants Welcome to Records Territory. In this edition we bring news of The Northern Territory History Grants for 2005 were advertised in lots of archives collecting activity and snapshots of the range of The Australian and local Northern Territory newspapers in mid- archives in our collections including a spotlight on Cyclone Tracy March this year. The grants scheme provides an annual series of following its 30th anniversary last December. Over the past few fi nancial grants to encourage and support the work of researchers months the NT Archives Service has been busily supporting who are recording and writing about Northern Territory history. research projects through both our public search room and the The closing date for applications was May 06 2005. NT History Grants program. Details of successful History Grant recipients for 2004 can be On the Government Recordkeeping front, we have passed found on page 10. the fi rst milestone of monitoring agency compliance with the We congratulate the following History Grants recipients for Information Act and have survived the fi rst full year of managing completion of their research projects for which they received part our responsibilities under the Act. Other initiatives have or total assistance from the N T History Grants Program. included the establishment of a records retention and disposal review committee and continued coordination of an upgrade of Robert Gosford – Annotated Chronological Bibliography – Northern the government’s records management system TRIM. Territory Ethnobiology 1874 to 2004 John Dargavel – Persistance and transition on the Wangites-Wagait We are currently celebrating the long awaited implementation reserves, 1892-1976 ( Journal of Northern Territory History Issue No of the archives management system, although there is a long 15, 2004, pp 5 – 19) journey ahead to load all of the relevant information to assist us and our researchers. -

The Honourable Sir Peter Cosgrove AK AC(MIL) CVO MC (Retd)

The Honourable Sir Peter Cosgrove AK AC(MIL) CVO MC (Retd) Australian Statesman, Keynote Speaker General the Honourable Sir Peter Cosgrove AK AC(Mil) CVO MC (Retd) is known as ‘a man of the people’. When recognised in 2001 as Australian of the Year, it was said that, “In every respect Peter Cosgrove demonstrated that he is a role model. The man at the top displayed those characteristics we value most as Australians – strength, determination, intelligence, compassion and humour.” Having led troops as a junior leader and as Commander-in-Chief, having served as Australia’s Governor General from 2014 to 2019, and having travelled the world and Australia, General the Honourable Sir Peter Cosgrove has unique perspectives on Australia, Australians and our place in the world. His views on leadership are grounded in experience, his keynotes are insightful, entertaining and revealing. More about General the Honourable Sir Peter Cosgrove: The son of a soldier, Peter Cosgrove attended Waverley College in Sydney and later graduated from the Royal Military College, Duntroon, in 1968. He was sent to Malaysia as a lieutenant in the 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment. During his next infantry posting in Vietnam he commanded a rifle platoon and was awarded the Military Cross for his performance and leadership during an assault on enemy positions. With his wife Lynne, the next twenty years saw the family grow to three sons and a wide variety of defence force postings, including extended duty in the UK and India. In 1999 Peter Cosgrove became a national figure following his appointment as Commander of the International Force East Timor (INTERFET). -

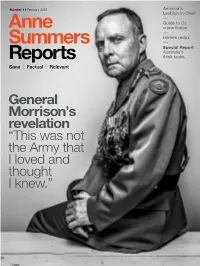

2015 Anne Summers Issue 11 2015

Number 11 February 2015 America’s Lesbian-in-Chief Guide to Oz crime fiction Harlem redux Special Report Australia’s think tanks Sane Factual Relevant General Morrison’s revelation “This was not the Army that I loved and thought I knew.” #11 February 2015 I HOPE YOU ENJOY our first issue for 2015, and our eleventh since we started our digital voyage just over two years ago. We introduce Explore, a new section dealing with ideas, science, social issues and movements, and travel, a topic many of you said, via our readers’ survey late last year, you wanted us to cover. (Read the full results of the survey on page 85.) I am so pleased to be able to welcome to our pages the exceptional mrandmrsamos, the husband-and-wife team of writer Lee Tulloch and photographer Tony Amos, whose piece on the Harlem revival is just a taste of the treats that lie ahead. No ordinary travel writing, I can assure you. Anne Summers We are very proud to publish our first investigative special EDITOR & PUBLISHER report on Australia’s think tanks. Who are they? Who runs them? Who funds them? How accountable are they and how Stephen Clark much influence do they really have? In this landmark piece ART DIRECTOR of reporting, Robert Milliken uncovers how thinks tanks are Foong Ling Kong increasingly setting the agenda for the government. MANAGING EDITOR In other reports, you will meet Merryn Johns, the Australian woman making a splash as a magazine editor Wendy Farley in New York and who happens to be known as America’s Get Anne Summers DESIGNER Lesbian-in-Chief. -

Law Review L

Adelaide Adelaide Law Law ReviewReview 2015 2015 Adelaide Law Review 2015 TABLETABLE OF OF CONTENTS CONTENTS ARTICLES THEArronTHE 2011 Honniball 2011 JOHN JOHN BRAY BRAY ORATIONPriv ORATIONate Political Activists and the International Law Definition of Piracy: Acting for ‘Private Ends’ 279 DavidDavid Irvine Irvine FreeFrdomeedom and and Security: Security: Maintaining Maintaining The The Balance Balance 295 295 Chris Dent Nordenfelt v Maxim-Nordenfelt: An Expanded ARTICLESARTICLES Reading 329 THETHE UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF OF ADELAIDE ADELAIDE JamesTrevorJames Allan Ryan, Allan and andProtecting Time Time and and Chance the Chance Rights and and theof the ThosePrevailing Prevailing with Orthodoxy Dementia Orthodoxy in in ADELAIDEADELAIDE LAW LAW REVIEW REVIEW AnthonyBruceAnthony Baer Senanayake Senanayake Arnold ThroughLegalLegal Academia AcademiaMandatory Happeneth Happeneth Registration to Themto Them of All All — —A StudyA Study of theof the Top Top Law Law Journals Journals of Australiaof Australia and and New New Ze alandZealand 307 307 ASSOCIATIONASSOCIATION and Wendy Bonython Enduring Powers? A Comparative Analysis 355 LaurentiaDuaneLaurentia L McOstler McKessarKessar Legislati Three Three Constitutionalve Constitutional Oversight Themes of Themes a Bill in theofin theRights: High High Court Court Theof Australia:of American Australia: 1 SeptemberPerspective 1 September 2008–19 2008–19 June June 201 20010 387347347 ThanujaKimThanuja Sorensen Rodrigo Rodrigo To Unconscionable Leash Unconscionable or Not Demands to Demands Leash -

Ministerial Staff Under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution Or Black Hole?

Ministerial Staff Under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution or Black Hole? Author Tiernan, Anne-Maree Published 2005 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Department of Politics and Public Policy DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3587 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367746 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Ministerial Staff under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution or Black Hole? Anne-Maree Tiernan BA (Australian National University) BComm (Hons) (Griffith University) Department of Politics and Public Policy, Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2004 Abstract This thesis traces the development of the ministerial staffing system in Australian Commonwealth government from 1972 to the present. It explores four aspects of its contemporary operations that are potentially problematic. These are: the accountability of ministerial staff, their conduct and behaviour, the adequacy of current arrangements for managing and controlling the staff, and their fit within a Westminster-style political system. In the thirty years since its formal introduction by the Whitlam government, the ministerial staffing system has evolved to become a powerful new political institution within the Australian core executive. Its growing importance is reflected in the significant growth in ministerial staff numbers, in their increasing seniority and status, and in the progressive expansion of their role and influence. There is now broad acceptance that ministerial staff play necessary and legitimate roles, assisting overloaded ministers to cope with the unrelenting demands of their jobs. However, recent controversies involving ministerial staff indicate that concerns persist about their accountability, about their role and conduct, and about their impact on the system of advice and support to ministers and prime ministers. -

Sas Resources Fund History 1996-2016

SPECIAL AIR SERVICE RESOURCES FUND 5 SAS RESOURCES FUND HISTORY 1996-2016 November 2016 SPECIAL AIR SERVICE RESOURCES FUND 6 FOREWORD If there was one single glimmer of light to emerge from the ashes of the 1996 Blackhawk disaster, it would certainly be the creation of the Special Air Service Resources Fund. While the unit was understandably reeling from its worst ever loss, and rightfully focused on rebuilding the short notice Counter Terrorism capability that Australia relies upon it to provide, a selfless group of individuals coalesced, unprompted, and set about creating this amazing institution. In doing so, they reacted swiftly, decisively and generously; and have continued to ever since. The 20 years since the Blackhawk tragedy represents about a “generation” within the Special Air Service Regiment; the unit’s most senior soldiers today were young troopers or lance corporals back in 1996 when the accident occurred. Sadly, during that generation, almost every single member of the unit has experienced the loss of a friend in training or combat. But on each occasion, in the midst of their grief, our men and women have also seen the Fund immediately step into action. As a result, we have witnessed the children of our fallen mates grow up, being cared for by the Fund. No one can replace a lost father or husband but through its financial support and empathy, the Fund provides a backbone of solace in this darkest of situations. By virtue of this fact, every time our soldiers step forward into the breach, they do so confident in the knowledge that should they fall in the service of this country, the Fund has their back, and will continue to take care of that which is most precious to them. -

Does the Media Fail Aboriginal Political Aspirations?

DOES THE MEDIA 45 years of news media reporting of FAIL ABORIGINAL key political moments POLITICAL Amy Thomas Andrew Jakubowicz ASPIRATIONS? Heidi Norman AIATSIS Research Publications DOES THE MEDIA FAIL ABORIGINAL POLITICAL ASPIRATIONS? 45 years of news media reporting of key political moments Amy Thomas Andrew Jakubowicz Heidi Norman DOES THE MEDIA FAIL ABORIGINAL POLITICAL ASPIRATIONS? First published in 2019 by Aboriginal Studies Press Copyright @ New South Wales Government All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by an information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing form the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, which ever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its education purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. The opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the view of AIATSIS or ASP. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are respectfully advised that this publication contains names and images of deceased persons and culturally sensitive information. ISBN: 9780855750848 (pb) ISBN: 9780855750855 (ePub) ISBN: 9780855750862 (kindle) ISBN: 9780855750930 (ebook PDF) Printed in Australia by Ligare Design and Typsetting by 33 Creative Cover image: Tessa Ferguson and Edwin Jangalaros presenting the Larrakia petition outside Government House, Darwin. The petition was 3.3 metres long, featuring one thousand signatures and thumbprints collected by Gwalwa Daraniki. -

Geography, Power, Strategy & Defence Policy

GEOGRAPHY, POWER, STRATEGY & DEFENCE POLICY ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF PAUL DIBB GEOGRAPHY, POWER, STRATEGY & DEFENCE POLICY ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF PAUL DIBB Edited by Desmond Ball and Sheryn Lee Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Geography, power, strategy and defence policy : essays in honour of Paul Dibb / editors: Desmond Ball, Sheryn Lee. ISBN: 9781760460136 (paperback) 9781760460143 (ebook) Subjects: Dibb, Paul, 1939---Criticism and interpretation. Defensive (Military science) Military planning--Australia. Festschriften. Australia--Military policy. Australia--Defenses. Other Creators/Contributors: Ball, Desmond, 1947- editor. Lee, Sheryn, editor. Dewey Number: 355.033594 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: SDSC Photograph Collection. This edition © 2016 ANU Press Contents Acronyms ..............................................vii Contributors ............................................ xi Photographs and Maps ..................................xvii Introduction .............................................1 Desmond Ball and Sheryn Lee 1. Introducing Paul Dibb (1): Britain’s Loss, Australia’s Gain ......15 Allan Hawke 2. Introducing Paul Dibb (2): An Enriching Experience ...........21 Chris Barrie 3. Getting to Know Paul Dibb: An Overview of an Extraordinary Career ..................................25 Desmond Ball 4. Scholar, Spy, Passionate Realist .........................33 Geoffrey Barker 5. The Power of Geography ..............................45 Peter J. Rimmer and R. Gerard Ward 6. The Importance of Geography ..........................71 Robert Ayson 7.