Law Review L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radical Islamist Groups in the Modern Age

WORKING PAPER NO. 376 RADICAL ISLAMIST GROUPS IN THE MODERN AGE: A CASE STUDY OF HIZBULLAH Lieutenant-Colonel Rodger Shanahan Canberra June 2003 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Shanahan, Rodger, 1964-. Radical Islamist Groups in the Modern Age: A Case Study of Hizbullah Bibliography. ISBN 0 7315 5435 3. 1. Hizballah (Lebanon). 2. Islamic fundamentalism - Lebanon. 3. Islam and politics - Lebanon. 4. Terrorism - Religious aspects - Islam. I. Title. (Series : Working paper (Australian National University. Strategic and Defence Studies Centre) ; no.376). 322.42095692 Strategic and Defence Studies Centre The aim of the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, which is located in the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies in the Australian National University, is to advance the study of strategic problems, especially those relating to the general region of Asia and the Pacific. The centre gives particular attention to Australia’s strategic neighbourhood of Southeast Asia and the Southwest Pacific. Participation in the centre’s activities is not limited to members of the university, but includes other interested professional, diplomatic and parliamentary groups. Research includes military, political, economic, scientific and technological aspects of strategic developments. Strategy, for the purpose of the centre, is defined in the broadest sense of embracing not only the control and application of military force, but also the peaceful settlement of disputes that could cause violence. This is the leading academic body in Australia specialising in these studies. Centre members give frequent lectures and seminars for other departments within the ANU and other universities and Australian service training institutions are heavily dependent upon SDSC assistance with the strategic studies sections of their courses. -

Alan Oakley Sent: Thursday, 15 May 2008 5:08 PM To: Joanne Puccini Subject: RE: Media Watch Query

From: Alan Oakley Sent: Thursday, 15 May 2008 5:08 PM To: Joanne Puccini Subject: RE: Media watch query Hi Joanne, Thanks for the inquiry. I never discuss why something is or isn't published, suffice to say it's called editing and it happens daily. I don't discuss the performance of individual journalists in a public forum; I find it more constructive to talk to them. I don't discuss how reporters are briefed for assignments; only they need to know. regards, Alan From: Joanne Puccini Sent: Thursday, 15 May 2008 12:54 PM To: Alan Oakley; Sue Ritchie Subject: Media watch query Alan Oakley Editor The Sydney Morning Herald By email 15 May 2008 Dear Alan, On Saturday May 10th, The Age published a lengthy "farewell" report by Fairfax's departing Middle East correspondent Ed O'Loughlin. We understand that the same piece, albeit perhaps subbed somewhat differently, was due to be published in the Sydney Morning Herald's News Review section the same day. However, it did not appear and has not been published subsequently in the Herald. - Could you tell us why you decided not to run this report in The Sydney Morning Herald? There has been frequent criticism of Mr O’Loughlin’s reporting by some supporters of Israel, who appear to believe that he is overly critical of Israel and the IDF, overly sympathetic to the Palestinian point of view, and insufficiently critical of Hamas. (For example, by Michael Danby MP; Mr Tzvi Fleischer, Editor-in-Chief of AIJAC’s Australia/Israel Review; and by AIJAC’s Jamie Hyams, to name a few.) - Did these criticisms of his reporting by the so-called “Jewish/Israel lobby” in any way influence your decision not to run Ed O'Loughlin's final report? Shortly after the announcement of his appointment to replace Ed O’Loughlin as Fairfax’s Jerusalem-based Middle East correspondent, Jason Koutsoukis was reported by the Australian Jewish News as saying: “There's two sides to every story and I think we've got to tell both sides. -

Ambassade De France En Australie – Service De Presse Et Information Site : Tél

Online Press review 22 April 2015 The articles in purple are not available online. Please contact the Press and Information Department. FRONT PAGE ALP eyes super tax hit for wealthy (AUS) Maher Up to 170,000 Australians face higher superannuation taxes under Labor plans to tackle the budget deficit by raising $14 billion during the next decade from wealthier workers and retirees. British terror links extend to second investigation (AUS) Schliebs, Wallace Authorities have established links between Australian and British men in two separate terrorism •investigations in recent months, with different groups of people in both countries questioned over their ties to alleged plots. Labor's $14b superannuation hit to well-off (AFR) Coorey The well-off would lose $14 billion in superannuation tax concessions over the next decade under a new Labor policy that it says is needed to keep the system sustainable and restore equity. DOMESTIC AFFAIRS POLITICS Let’s educate the upper house pygmies about democracy (AUS/Opinion) Craven Traditionally, there were two routes to certain social death in Australia. One was barracking for Collingwood. The other was membership of an upper house of parliament. MELBOURNE TERROR ARRESTS Teenage terror accused set up, father declares (AUS) Akerman The father of a teenager accused of conspiring to plan a terrorist attack has pleaded his son’s innocence, declaring the youth has been “set up”. Melbourne's al-Furqan Islamic centre a key focus for ASIO (AUS) Baxendale When the founders of the al-Furqan Islamic centre in Melbourne’s Springvale South applied to the City of Greater Dandenong for “place of assembly” and “information centre” permits in 2011, they were refused on the grounds of parking, noise and safety. -

Digital Edition

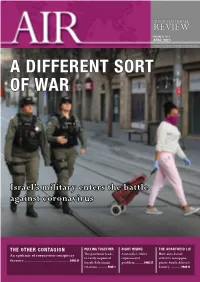

AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL REVIEW VOLUME 45 No. 4 APRIL 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL & JEWISH AFFAIRS COUNCIL A DIFFERENT SORT OF WAR Israel’s military enters the battle against coronavirus THE OTHER CONTAGION PULLING TOGETHER RIGHT RISING THE APARTHEID LIE An epidemic of coronavirus conspiracy The pandemic leads Australia’s white How anti-Israel to vastly improved supremacist activists misappro- theories ............................................... PAGE 21 Israeli-Palestinian problem ........PAGE 27 priate South Africa’s relations .......... PAGE 7 history ........... PAGE 31 WITH COMPLIMENTS NAME OF SECTION L1 26 BEATTY AVENUE ARMADALE VIC 3143 TEL: (03) 9661 8250 FAX: (03) 9661 8257 WITH COMPLIMENTS 2 AIR – April 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL VOLUME 45 No. 4 REVIEW APRIL 2020 EDITOR’S NOTE NAME OF SECTION his AIR edition focuses on the Israeli response to the extraordinary global coronavirus ON THE COVER Tpandemic – with a view to what other nations, such as Australia, can learn from the Israeli Border Police patrol Israeli experience. the streets of Jerusalem, 25 The cover story is a detailed look, by security journalist Alex Fishman, at how the IDF March 2020. Israeli authori- has been mobilised to play a part in Israel’s COVID-19 response – even while preparing ties have tightened citizens’ to meet external threats as well. In addition, Amotz Asa-El provides both a timeline of movement restrictions to Israeli measures to meet the coronavirus crisis, and a look at how Israel’s ongoing politi- prevent the spread of the coronavirus that causes the cal standoff has continued despite it. Plus, military reporter Anna Ahronheim looks at the COVID-19 disease. (Photo: Abir Sultan/AAP) cooperation the emergency has sparked between Israel and the Palestinians. -

THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Law.Adelaide.Edu.Au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD

Volume 40, Number 3 THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW law.adelaide.edu.au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD The Honourable Professor Catherine Branson AC QC Deputy Chancellor, The University of Adelaide; Former President, Australian Human Rights Commission; Former Justice, Federal Court of Australia Emeritus Professor William R Cornish CMG QC Emeritus Herchel Smith Professor of Intellectual Property Law, University of Cambridge His Excellency Judge James R Crawford AC SC International Court of Justice The Honourable Professor John J Doyle AC QC Former Chief Justice, Supreme Court of South Australia Professor John V Orth William Rand Kenan Jr Professor of Law, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Professor Emerita Rosemary J Owens AO Former Dean, Adelaide Law School The Honourable Justice Melissa Perry Federal Court of Australia The Honourable Margaret White AO Former Justice, Supreme Court of Queensland Professor John M Williams Dame Roma Mitchell Chair of Law and Former Dean, Adelaide Law School ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Editors Associate Professor Matthew Stubbs and Dr Michelle Lim Book Review and Comment Editor Dr Stacey Henderson Associate Editors Kyriaco Nikias and Azaara Perakath Student Editors Joshua Aikens Christian Andreotti Mitchell Brunker Peter Dalrymple Henry Materne-Smith Holly Nicholls Clare Nolan Eleanor Nolan Vincent Rocca India Short Christine Vu Kate Walsh Noel Williams Publications Officer Panita Hirunboot Volume 40 Issue 3 2019 The Adelaide Law Review is a double-blind peer reviewed journal that is published twice a year by the Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide. A guide for the submission of manuscripts is set out at the back of this issue. -

E – N E W S : New Australian Government 2013

E – N E W S : New Australian Government 2013 New Australian Government led by the Leader of the Liberal Party, the Hon Tony Abbott MP, and his cabinet were sworn in by the Governor-General Quentin Bryce on Wednesday 18 September 2013. Australian Embassy Zagreb September 2013 Issue 65 The Hon Tony Abbott MP, was sworn in as the 28th Prime Minister of Australia on 18 Septem- ber 2013. Prior to the election of the Coalition Government on 7 September 2013, Mr Abbott had been Leader of the Opposition since 1 December 2009. Mr Abbott was first elected as Member for War- ringah in March 1994. He has been re-elected as Member for Warringah at seven subsequent elec- tions. During the Howard Government, Mr Abbott served as a Parliamentary Secretary, Minister, Cabi- net Minister, and Leader of the House of Representatives. Read more: here The Hon Julie Bishop MP was sworn in as Australia’s 38th Minister for Foreign Affairs. Ms Bishop will assume this senior frontbench position at a critical time in international relations; when Australia is President of the United Nations Security Council, and as Australia assumes the Chair of the G20 in December. “I am proud to be Australia’s first female Foreign Minister and I look forward to promoting and protecting the interests of Australia and Australians,” Ms Bishop said. Read more: here Senator the Hon Brett Mason, Andrew Robb AO MP, Minister for Parliamentary Secretary to the Trade and Investment Minister for Foreign Affairs Read more : here Read more: here Australian Federal Election 2013 Australians who were listed on the current electoral roll were eligible to vote whilst overseas. -

University of Adelaide, Australia 13 – 20 January 2019

GATEWAY TO COMMON LAW University of Adelaide, Australia 13 – 20 January 2019 adelaide.edu.au THE UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE Study common law at one of the oldest universities in the Southern Hemisphere. This intensive one-week program is specifically designed for advanced undergraduate students who would like to study common law system from a comparative perspective. Taught by experienced academic staff from Adelaide Law School, Australia’s second oldest law school established in 1874, students will grasp great knowledge of various aspects of Australian legal system. COST: $1,400 AUD LECTURES & FIELD TRIPS SEMINARS WELCOMING LEARNING LUNCH MATERIALS 7 NIGHTS LIBRARY ACCOMMODATION (Single room, breakfast ACCESS and dinner included) ON-CAMPUS CERTIFICATE OF WI-FI ATTENDANCE Gateway to Common Law University of Adelaide, Australia, 13 – 20 January 2019 STUDY IN CAFÉ CULTURE Adelaide is one of Australia’s most cosmopolitan cities, with an array of cafés, restaurants and shops reflecting the diversity of its ethnic communities. Adelaide is reputed THE CENTRE OF to have more cafés and restaurants SHOPPING per head of population than any Adelaide boasts a range of other city in Australia. shopping experiences comparable to anywhere in Australia. Within the CBD, Rundle Mall ADELAIDE has the biggest concentration of department and chain stores, while within walking distance are Adelaide Law School is located in the trendy boutiques, pubs and cafés. University of Adelaide’s North Terrace Campus, in the city centre of Adelaide, capital of South Australia. Students will study in a modern campus with shining historical buildings, and within walking distance to South Australia Parliament, Museum, State Library, Art Gallery and CBD. -

The Adelaide Law School 1883-1983

THE ADELAIDE LAW SCHOOL 1883-1983 by Victor Allen Edgeloe Dr Edgeloe, Registrar Emeritus of the University of Adelaide, was Secretary of the Faculty of Law from 1927 to 1948, and Registrar from 1955 to 1973. Since his retirement Dr Edgeloe has written an account of the foundation and development of the Faculties of Law, Medicine and Music. His aim was, as he states in the preface, "to provide an administrator's history of the birth of the University's schools of law, medicine and music" which '%umrnarises the relevant records of the University and the relevant comments of the public press of the day". The manuscript is held in the Barr Smith Library. It shows Dr Edgeloe's love of, and devotion to, the University which he served for forty-six years. The Adelaide Law Review Association is grateful to him for permission to include his history of the Law School in this collection of essays. The Beginnings In the 1870's the Province of South Australia was a pioneering community which was expanding rapidly in numbers and in area occupied. There was a clear need for a growing body of well-trained lawyers. The existing arrangements for the training of lawyers involved simply the satisfactory completion of a five-year apprenticeship with a legal practitioner (technically designated "service in articles") and the passing of a small range of examinations conducted by the Supreme Court. University teaching in law was available in the United Kingdom and had also been established in Melbourne.' The South Australian Parliament envisaged a similar development here for it empowered the University from its foundation in 1874 to confer degrees in law and thus give the University a major role in the training of members of the legal profession within the Province. -

1 March 2019 at 9 Am

__________________________________________________________ PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION COMPENSATION AND REHABILITATION FOR VETERANS MR R FITZGERALD Commissioner MR R SPENCER, Commissioner TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS HOTEL GRAND CHANCELLOR, 334 FLINDERS STREET, TOWNSVILLE ON FRIDAY 1 MARCH 2019 AT 9 AM Compensation and Rehabilitation for Veterans 1/03/19 Townsville © C'wlth of Australia INDEX Pages JOHN CALIGARI 1324 - 1342 PHILLIP BURTON 1342 - 1356 TPDESA TOWNSVILLE/RSL TOWNSVILLE 1357 - 1369 RAY MARTIN 1370 - 1379 LAWRENCE CHARLES WHITE 1380 - 1386 JOHN ERNEST WILLIAMS 1386- 1390 PETER HINDLE 1390 - 1397 SARAH MOLLOY 1397 - 1404 Compensation and Rehabilitation for Veterans 1/03/19 Townsville © C'wlth of Australia COMMISSIONER FITZGERALD: If we can just grab some seats. If you're hard of hearing I suggest you just sit down the front a little. If you're almost completely deaf let me know and we've got a separate microphone. These microphones don't amplify. They're only for 5 recording purposes. So, again, if you can't hear anybody let us know, we have another microphone. Good morning and thank you very much for attending and welcome to this public hearing of the Productivity Commission's inquiry into veterans 10 compensation and rehabilitation following the release of our draft report in December. So I'll just make a short statement which we make at the beginning of each of these hearings. I'm Robert Fitzgerald, I'm the Presiding Commissioner 15 on this inquiry, and my colleague is Commissioner Richard Spencer. First off I'd like to express our appreciation for you giving your time to attend these hearings, particularly following the recent floods or significant weather event, however you describe it, and we do understand 20 that there would've been people who wanted to participate today but are engaged in the recovery process and are unable to do so. -

'The Bougainville Conflict: a Classic Outcome of the Resource-Curse

The Bougainville conflict: A classic outcome of the resource-curse effect? Michael Cornish INTRODUCTION Mismanagement of the relationship between the operation of the Panguna Mine and the local people was a fundamental cause of the conflict in Bougainville. It directly created great hostility between the people of Bougainville and the Government of Papua New Guinea. Although there were pre-existing ethnic and economic divisions between Bougainville and the rest of Papua New Guinea, the mismanagement of the copper wealth of the Panguna Mine both exacerbated these existing tensions and provided radical Bougainvilleans an excuse to legitimise the pursuit of violence as a means to resolve their grievances. The island descended into anarchy, and from 1988 to 1997, democracy and the rule of law all but disappeared. Society fragmented and economic development reversed as the pillage and wanton destruction that accompanied the conflict took its toll. Now, more than 10 years since the formal Peace Agreement1 and over 4 years since the institution of the Autonomous Bougainville Government, there are positive signs that both democracy and development are repairing and gaining momentum. However, the untapped riches of the Panguna Mine remain an ominous issue that will continue to overshadow the region’s future. How this issue is handled will be crucial to the future of democracy and development in Bougainville. 1 Government of the Independent State of Papua New Guinea and Leaders representing the people of Bougainville, Bougainville Peace Agreement , 29 August 2001 BACKGROUND Bougainville is the name of the largest island within the Solomon Islands chain in eastern Papua New Guinea, the second largest being Buka Island to its north. -

Australia's Relations with Iran

Policy Paper No.1 October 2013 Shahram Akbarzadeh ARC Future Fellow Australia’s Relations with Iran Policy Paper 1 Executive summary Australia’s bilateral relations with Iran have experienced a decline in recent years. This is largely due to the imposition of a series of sanctions on Iran. The United Nations Security Council initiated a number of sanctions on Iran to alter the latter’s behavior in relation to its nuclear program. Australia has implemented the UN sanctions regime, along with a raft of autonomous sanctions. However, the impact of sanctions on bilateral trade ties has been muted because the bulk of Australia’s export commodities are not currently subject to sanctions, nor was Australia ever a major buyer of Iranian hydrocarbons. At the same time, Australian political leaders have consistently tried to keep trade and politics separate. The picture is further complicated by the rise in the Australian currency which adversely affected export earnings and a drought which seriously undermined the agriculture and meat industries. Yet, significant political changes in Iran provide a window of opportunity to repair relations. Introduction Australian relations with the Islamic Republic of Iran are complicated. In recent decades, bilateral relations have been carried out under the imposing shadow of antagonism between Iran and the United States. Australia’s alliance with the United States has adversely affected its relations with Iran, with Australia standing firm on its commitment to the United States in participating in the War on Terror by sending troops to Afghanistan and Iraq. Australia’s continued presence in Afghanistan, albeit light, is testimony to the close US-Australia security bond. -

Can Academic Freedom in Faith-Based Colleges and Universities Survive During the Era of Obergefell?

CAN ACADEMIC FREEDOM IN FAITH-BASED COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES SURVIVE DURING THE ERA OF OBERGEFELL? Charles J. Russo† INTRODUCTION On August 15, 1990, Saint Pope John Paul II promulgated Ex Corde Ecclesiae (“Ex Corde”),1 literally, “From the Heart of the Church,” an apostolic constitution about Roman Catholic colleges and universities. By definition, apostolic constitutions address important matters concerning the universal Church.2 Ex Corde created a tempest in a teapot for academicians by requiring Roman Catholics who serve on faculties in theology, religious studies, and/or related departments in Catholic institutions of higher education to obtain a Mandatum, or mandate, from their local bishops, essentially a license certifying the faithfulness of their teaching and writing in terms of how they present the magisterial position of the Church.3 † B.A., 1972, St. John’s University; M. Div., 1978, Seminary of the Immaculate Conception; J.D., 1983, St. John’s University; Ed.D., 1989, St. John’s University; Panzer Chair in Education and Adjunct Professor of Law, University of Dayton (U.D.). I extend my appreciation to Dr. Paul Babie, D. Phil., Professor of Law and Legal Theory, Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide, Australia; Dr. Suzanne E. Eckes, Professor, Professor, Department of Teacher Leadership and Policy Studies, Indiana University; Dr. Ralph Sharp, Associate Professor Emeritus, East Central University, Ada, Oklahoma; William E. Thro, General Counsel and Adjunct Professor of Law, University of Kentucky; and Professor Lynn D. Wardle, Bruce C. Hafen Professor of Law, J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, for their useful comments on drafts of the manuscript.