Causes of the American Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grade 6 Reading Student At–Home Activity Packet

Printer Warning: This packet is lengthy. Determine whether you want to print both sections, or only print Section 1 or 2. Grade 6 Reading Student At–Home Activity Packet This At–Home Activity packet includes two parts, Section 1 and Section 2, each with approximately 10 lessons in it. We recommend that your student complete one lesson each day. Most lessons can be completed independently. However, there are some lessons that would benefit from the support of an adult. If there is not an adult available to help, don’t worry! Just skip those lessons. Encourage your student to just do the best they can with this content—the most important thing is that they continue to work on their reading! Flip to see the Grade 6 Reading activities included in this packet! © 2020 Curriculum Associates, LLC. All rights reserved. Section 1 Table of Contents Grade 6 Reading Activities in Section 1 Lesson Resource Instructions Answer Key Page 1 Grade 6 Ready • Read the Guided Practice: Answers will vary. 10–11 Language Handbook, Introduction. Sample answers: Lesson 9 • Complete the 1. Wouldn’t it be fun to learn about Varying Sentence Guided Practice. insect colonies? Patterns • Complete the 2. When I looked at the museum map, Independent I noticed a new insect exhibit. Lesson 9 Varying Sentence Patterns Introduction Good writers use a variety of sentence types. They mix short and long sentences, and they find different ways to start sentences. Here are ways to improve your writing: Practice. Use different sentence types: statements, questions, imperatives, and exclamations. Use different sentence structures: simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex. -

Advanced Study Guide

Mike Wiley – The Playwright and Actor Actor and playwright Mike Wiley has spent the last decade fulfilling his mission to bring educational theatre to young audiences. In the early days of his career, Wiley found few theatrical resources to shine light on key events and figures in black history. To bring these often ignored stories to life, Wiley started his own production company. Through his work, he has introduced countless students to the stories and legacies of Emmett Till, the Tuskegee Airmen, Henry “Box” Brown and more. Most recently he has brought Timothy B. Tyson’s acclaimed book “Blood Done Sign My Name” to the stage. Mike Wiley has a Masters of Fine Arts from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has appeared on the Discovery Channel, The Learning Channel and the National Geographic Channel and was recently profiled in Our State magazine. Synopsis Henry “Box” Brown was an African American born into slavery in 1816 in Louisa County, Virginia. Although he was not subjected to physical violence, Henry’s story (the basis for One Noble Journey) demonstrates the cruelty of slavery was every bit as devastating to the heart as it could be on the body. At the death of his master, Henry’s family was torn apart and parceled out to various beneficiaries of the estate. Henry, who was 33 at the time, was bequeathed to his master’s son and sent to work in Richmond, VA. While there, he experienced the joys of marriage and children, only to have slavery lash his heart again. Henry’s wife and children were taken from him, sold to North Carolina slave- holders and never seen again. -

BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans

U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans BRIEFING REPORT U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS Washington, DC 20425 Official Business DECEMBER 2018 Penalty for Private Use $300 Visit us on the Web: www.usccr.gov U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS MEMBERS OF THE COMMISSION The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is an independent, Catherine E. Lhamon, Chairperson bipartisan agency established by Congress in 1957. It is Patricia Timmons-Goodson, Vice Chairperson directed to: Debo P. Adegbile Gail L. Heriot • Investigate complaints alleging that citizens are Peter N. Kirsanow being deprived of their right to vote by reason of their David Kladney race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national Karen Narasaki origin, or by reason of fraudulent practices. Michael Yaki • Study and collect information relating to discrimination or a denial of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution Mauro Morales, Staff Director because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice. • Appraise federal laws and policies with respect to U.S. Commission on Civil Rights discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws 1331 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or Washington, DC 20425 national origin, or in the administration of justice. (202) 376-8128 voice • Serve as a national clearinghouse for information TTY Relay: 711 in respect to discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, www.usccr.gov religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin. • Submit reports, findings, and recommendations to the President and Congress. -

ENG 3705-001: Multicultural U. S. Literature Christopher Hanlon Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Summer 2012 2012 Summer 6-15-2012 ENG 3705-001: Multicultural U. S. Literature Christopher Hanlon Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/english_syllabi_summer2012 Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hanlon, Christopher, "ENG 3705-001: Multicultural U. S. Literature" (2012). Summer 2012. 7. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/english_syllabi_summer2012/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2012 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Summer 2012 by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I f :: - '~-1r ' ~;\... I I / .,.,- - ._......... ~ r ~~,,:. Professor Christopher Hanlon Coleman Hall 3811 Office Hours: MTuW 10:45-12:00 [email protected] Ifyou ask me, the very word "multiculturalism" has become a problem. In university-level literature classes, the pedagogy of multiculturalism descends from the work of the Modern Language Association's Radical Caucus, which during the 1970s worked to unloose literacy education from near-constant attachment to white male authors. The generation of literature professors who initiated the project of multicultural canon revision were explicit that the purposes behind their task were not only (1) to give voice to important writers who had been buried by generations of indifferent literacy historians, but also (2) to effect change in American social life. By teaching a more diverse canon of texts, literature professors would promote an openness to multiple traditions as opposed to investment in some monolithic One, and the inclusive ethos behind such undertaking would have salutary effects well beyond the classroom. -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

One Noble Journey National Standards and Study Guide

One Noble Journey National Standards and Study Guide • Synopsis • Discussion Questions • Words & Phrases to Know • Find Out More • Curriculum Standards Mike Wiley Productions 1999-2004 Mike Wiley Productions is a theatrical company specializing in African American History Plays. One Noble Journey is about the life of Henry “Box” Brown. Brown was an African American who was born a slave in 1816 in Louisa County, Virginia. At the age of thirty-three he was bequeathed to his master's son, who sent him to work in his tobacco factory in Richmond, VA under the authority of a relentlessly evil overseer. Although his experiences in slavery were comparatively mild, and he was not subjected to physical violence, Brown was not content to be a slave. One Noble Journey demonstrates that slavery was still unbearable even under the best of conditions. Brown was able to experience the joys of marriage and even children under slavery’s oppression but his wife and children were eventually taken from him and sold to North Carolina. That horrible incident was Brown’s breaking point and he devised an escape plan. He had himself sealed in a small wooden box and shipped to friends and freedom in Philadelphia. He later settled in Massachusetts and traveled around the northern states speaking against slavery. One Noble Journey dramatizes Brown’s life while demonstrating what an evening with “Brown: The Escaped Slave, Turned Abolitionist!” might be like. Within One Noble Journey is embedded the miraculous true account of Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom the narrative of William and Ellen Craft's escape from slavery. -

Jekyll and Hyde Plot, Themes, Context and Key Vocabulary Booklet

Jekyll and Hyde Plot, Themes, Context and key vocabulary booklet Name: 1 2 Plot Mr Utterson and his cousin Mr Enfield are out for a walk when they pass a strange-looking door Chapter 1 - (which we later learn is the entrance to Dr Jekyll's laboratory). Enfield recalls a story involving the Story of the door. In the early hours of one winter morning, he says, he saw a man trampling on a young girl. He Door chased the man and brought him back to the scene of the crime. (The reader later learns that the man is Mr Hyde.) A crowd gathered and, to avoid a scene, the man offered to pay the girl compensation. This was accepted, and he opened the door with a key and re-emerged with a large cheque. Utterson is very interested in the case and asks whether Enfield is certain Hyde used a key to open the door. Enfield is sure he did. That evening the lawyer, Utterson, is troubled by what he has heard. He takes the will of his friend Dr Chapter 2 - Jekyll from his safe. It contains a worrying instruction: in the event of Dr Jekyll's disappearance, all his Search for possessions are to go to a Mr Hyde. Mr Hyde Utterson decides to visit Dr Lanyon, an old friend of his and Dr Jekyll's. Lanyon has never heard of Hyde, and not seen Jekyll for ten years. That night Utterson has terrible nightmares. He starts watching the door (which belongs to Dr Jekyll's old laboratory) at all hours, and eventually sees Hyde unlocking it. -

Primary Document Reader

Across the Border: A Transnational Approach to Teaching the Underground Railroad Primary Document Reader Sponsored by the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History, The Harriet Tubman Institute for Research on the Global Migrations of African Peoples, and Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition. Sometimes standing on the Ohio River bluff, looking over on a free State, and as far north as my eyes could see, I have eagerly gazed upon the blue sky of the free North, which at times constrained me to cry out from the depths of my soul, Oh! Canada, sweet land of rest--Oh! When shall I get there? Oh, that I had the wings of a dove, that I might soar away to where there is no slavery; no clanking of chains, no captives, no lacerating of backs, no parting of husbands and wives; and where man ceases to be the property of his fellow man. These thoughts have revolved in my mind a thousand times. I have stood upon the lofty banks of the river Ohio, gazing upon the splendid steamboats, wafted with all their magnificence up and down the river, and I thought of the fishes of the water, the fowls of the air, the wild beasts of the forest, all appeared to be free, to go just where they pleased, and I was an unhappy slave! Henry Bibb, Sandwich, Canada West I was told before I left Virginia,--have heard it as common talk, that the wild geese were so numerous in Canada, and so bad, that they would scratch a man's eyes out; that corn wouldn't grow there, nor anything else but rice; that everything they had there was imported. -

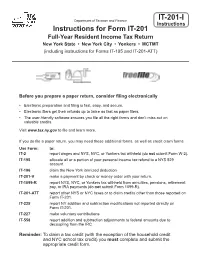

Instructions for Form IT-201 Full-Year Resident Income Tax Return

Department of Taxation and Finance IT-201-I Instructions Instructions for Form IT-201 Full-Year Resident Income Tax Return New York State • New York City • Yonkers • MCTMT (including instructions for Forms IT-195 and IT-201-ATT) Before you prepare a paper return, consider filing electronically • Electronic preparation and filing is fast, easy, and secure. • Electronic filers get their refunds up to twice as fast as paper filers. • The user-friendly software ensures you file all the right forms and don’t miss out on valuable credits. Visit www.tax.ny.gov to file and learn more. If you do file a paper return, you may need these additional forms, as well as credit claim forms. Use Form: to: IT-2 report wages and NYS, NYC, or Yonkers tax withheld (do not submit Form W-2). IT-195 allocate all or a portion of your personal income tax refund to a NYS 529 account. IT-196 claim the New York itemized deduction IT-201-V make a payment by check or money order with your return. IT-1099-R report NYS, NYC, or Yonkers tax withheld from annuities, pensions, retirement pay, or IRA payments (do not submit Form 1099-R). IT-201-ATT report other NYS or NYC taxes or to claim credits other than those reported on Form IT-201. IT-225 report NY addition and subtraction modifications not reported directly on Form IT-201. IT-227 make voluntary contributions IT-558 report addition and subtraction adjustments to federal amounts due to decoupling from the IRC. Reminder: To claim a tax credit (with the exception of the household credit and NYC school tax credit) you must complete and submit the appropriate credit form. -

Kingdom Principles

KINGDOM PRINCIPLES PREPARING FOR KINGDOM EXPERIENCE AND EXPANSION KINGDOM PRINCIPLES PREPARING FOR KINGDOM EXPERIENCE AND EXPANSION Dr. Myles Munroe © Copyright 2006 — Myles Munroe All rights reserved. This book is protected by the copyright laws of the United States of America. This book may not be copied or reprinted for commercial gain or profit. The use of short quotations or occasional page copying for personal or group study is permitted and encouraged. Permission will be granted upon request. Unless other- wise identified, Scripture quotations are from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNA- TIONAL VERSION Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked (NKJV) are taken form the New King James Version. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Please note that Destiny Image’s publishing style capitalizes certain pronouns in Scripture that refer to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and may differ from some publishers’ styles. Take note that the name satan and related names are not capitalized. We choose not to acknowledge him, even to the point of violating grammatical rules. Cover photography by Andy Adderley, Creative Photography, Nassau, Bahamas Destiny Image® Publishers, Inc. P.O. Box 310 Shippensburg, PA 17257-0310 “Speaking to the Purposes of God for this Generation and for the Generations to Come.” Bahamas Faith Ministry P.O. Box N9583 Nassau, Bahamas For Worldwide Distribution, Printed in the U.S.A. ISBN 10: 0-7684-2373-2 Hardcover ISBN 13: 978-0-7684-2373-0 ISBN 10: 0-7684-2398-8 Paperback ISBN 13: 978-0-7684-2398-3 This book and all other Destiny Image, Revival Press, MercyPlace, Fresh Bread, Destiny Image Fiction, and Treasure House books are available at Christian bookstores and distributors worldwide. -

Eng 3705-001: U.S

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Fall 2013 2013 Spring 8-15-2013 ENG 3705-001: U.S. Multicultural Literatures Christopher Hanlon Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/english_syllabi_fall2013 Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hanlon, Christopher, "ENG 3705-001: U.S. Multicultural Literatures" (2013). Fall 2013. 87. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/english_syllabi_fall2013/87 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2013 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fall 2013 by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 5-00{ ' 370 Professor Christopher Hanlon · Coleman Hall 3811 Office Hours: MWF 1,3 & by appointment [email protected] In university-level .literature classes, the rt•-prioritization of texts and methods collectively known as "multiculturalism"' descends from the work oftlw Modern Language Associatiou's Radical Caucus. which during the 1970s worked to unloose literary education from near-constant attachment to white male authors. The generation of literature professors who initiatNI multicultural rf,visious of the lJ.S. literacy canon were explicit that the purposes behind their task were not only (l) to give voice to important writers who had been h11ried by generations of indifferent literary historians. hut also (2) to effoct change i11 7\rncrican social, political, and economic life. By teaching a more diverse canon of texts and hy explicitly questioning the value-systems that had foreclosed that diversity. this generation of faculty wonld promote an opernwss to multiple traditions as opposed to exclusive attacli1nent to a white and rnalc one. -

Africa and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Africa and the transatlantic slave trade Arm ring trade token, The Manchester Museum, Barbados penny, TheObject University title of Manchester GalleryObject Oldham title Blackamoor, Bolton Museum and The Slave, ArchiveObject Service title People’s History Museum Questions Manilla, 1700s Slave Trade, 1791 West African drum, 1898 The Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester The Whitworth Art Gallery, The University of Manchester The Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester 1 Why did Europeans enslave Africans to work Manillas were traditional African The trade was described as George Morland was an English This painting was made as a piece This drum was collected in 1898 The drum is made with a piece horseshoe shaped bracelets triangular: ships sailed full of artist who did two paintings known of propaganda. It is not based in Ilorin, Nigeria. It was given to of manufactured cotton fabric, on plantations? made of metals such as iron, ‘exchange’ goods such as manillas, as ‘Slave Trade’ and ‘African on actual events, but represents Salford Museum and was described probably made in Britain, and bronze, copper and very rarely metals, clothing, guns and alcohol Hospitality’. He was inspired by a dramatisation of selling enslaved as ‘both rare and special and possibly in Manchester. 2 How did they justify this? gold. Decorative manillas were from Britain to Africa. Enslaved a friend’s poem to paint images Africans. European slave traders very difficult to get hold of’. The fact that British goods worn to show wealth and status Africans were transported across of slavery. The movement to end capture an African man, and Drums were a very important part became integral parts of African 3 What was life like in Africa? in Africa.