Evaluating Public Transit Benefits and Costs Best Practices Guidebook 31 August 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Deloitte City Mobility Index Gauging Global Readiness for the Future of Mobility

The Deloitte City Mobility Index Gauging global readiness for the future of mobility By: Simon Dixon, Haris Irshad, Derek M. Pankratz, and Justine Bornstein the Internet of Things, artificial intelligence, and Where should cities other digital technologies to develop and inform go tomorrow? intelligent decisions about people, places, and prod- ucts. A smart city is a data-driven city, one in which Unfortunately, when it comes to designing and municipal leaders have an increasingly sophisti- implementing a long-term vision for future mobil- cated understanding of conditions in the areas they ity, it is all too easy to ignore, misinterpret, or skew oversee, including the urban transportation system. this data to fit a preexisting narrative.1 We have seen In the past, regulators used questionnaires and sur- this play out in dozens of conversations with trans- veys to map user needs. Today, platform operators portation leaders all over the world. To build that can rely on databases to provide a more accurate vision, leaders need to gather the right data, ask the picture in a much shorter time frame at a lower cost. right questions, and focus on where cities should Now, leaders can leverage a vast array of data from go tomorrow. The Deloitte City Mobility Index Given the essential enabling role transportation theme analyses how deliberate and forward- plays in a city’s sustained economic prosperity,2 we thinking a city’s leaders are regarding its future set out to create a new and better way for city of- mobility needs. ficials to gauge the health of their mobility network 3. -

Canada's Natural Gas Vehicle (NGV) Industry Recognizes Transit

Canada’s Natural Gas Vehicle (NGV) Industry Recognizes Transit Agencies for NGV Leadership: Calgary Transit – for North America’s largest indoor refueling and maintenance facility BC Transit – for supporting NGVs in three communities Hamilton Street Railway – for Canada’s longest operating NGV transit fleet November 10, 2019 Calgary, Alberta Canadian Natural Gas Vehicle Alliance The Canadian Natural Gas Vehicle Alliance (CNGVA) is pleased to award its inaugural NGV Leadership Awards to Calgary Transit, BC Transit and Hamilton Street Railway. CNGVA’s first NGV Leadership Awards build on the collaborative efforts of industry and government in support of the NGV Deployment Roadmap: Natural Gas Use in the Medium and Heavy-Duty Transportation Sector – updated and recently released in collaboration with Natural Resources Canada. The awards celebrate market leadership in adopting natural gas as a fleet fuel and recognizing its environmental, economic and operational benefits. They recognize an operator’s investment in natural gas buses, training and infrastructure that has improved regional air quality, reduced greenhouse gas emissions and created local green jobs with an abundant, domestic resource. CNGVA applauds these fleet operators for their leadership and commitment to affordable, cleaner, quieter transportation. Calgary Transit Calgary Transit operates the public transit system in Alberta’s largest municipality. Operating a mixed fleet of LRT and bus vehicles, Calgary Transit is the first choice for getting around Calgary. The Stoney Transit Facility is a leading example of public-private partnerships (P3). The 44,300 square metre facility is the largest of its kind in North America, with the ability to simultaneously fuel six buses indoors from empty to full in about four minutes. -

Circulator Bus Transit Cost

Transit CIRCULATOR BUS TRANSIT COST DowntownDC, www.downtowndc.org TI SORT STATE ON REGI AL IPACT LOCAL RID OR OR C SPOT WO URDLS CITPRIAT FUNDIN TRANSIT ANCY More Information: tti.tamu.edu/policy/how-to-fix-congestion SUCCESS STORIES Description How Will This Help? Washington, D.C. Circulator bus transit is a short-distance, • Improves mobility and The DC Circulator is a circular, fixed-route transit mode that circulation in target areas. cooperative effort of the District takes riders around a specific area with • Fosters the redevelopment of Columbia Department of major destinations. It may include street- of urban spaces into walk- Transportation, the Washington cars, rubber-tire trolleys, electric buses, able, mixed-use, high-density Metropolitan Area Transit or compressed natural gas buses. environments. Authority, DC Surface Transit, and First Transit. The DC Two common types of circulator bus • Improves parking availability in transit are downtown circulators and areas with shortages. Circulator began service in neighborhood circulators. A circulator • Reduces environmental 2005 and has bus system targeted at tourists/visitors impacts from private/individual experienced is more likely to use vehicle colors to be transportation. increasing clearly identifiable. ridership each Implementation Issues year. Target Market There are many barriers, constraints, and Most downtown circulators are orient- obstacles to successfully implement, ed toward employee and tourist/visi- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania operate, and maintain a circulator bus. tor markets. Neighborhood circulators The Independence Visitor However, funding is the major constraint meet the mobility needs of transit-reliant Center Corporation manages in most programs. Inadequate funding populations, such as low-income and the downtown circulator, and costs were the most common mobility-challenged people. -

Traveling Airport Mascot

A CORPORATE PUBLIcaTION BY THE AUGUSTA REGIONAL AIRPORT Mascot • Boarding Pass goes MoBile • Parking shuttle WINTER 2014 AGS Introduces a Traveling Airport Mascot Augusta Regional Airport (AGS) has initiated a new Airport Mascot Program. This program has been established to honor AGS’s former canine employee, Mayday. Mayday was AGS’s longtime employee who spent ten years keeping airport passengers safe by chasing birds and other wildlife off and away from the runways. She will be represented by two traveling plush border collie rides with pilots and/or passengers The two mascots will be posting companions, Mayday and Little Miss transiting through general aviation pictures, videos and comments from Mayday. Together these two travelers terminals located in airports around their travels on their social media will promote the love of aviation in the world. channels so anyone who is interested may follow their adventures. the hearts of the young and old alike! Little Miss Mayday will temporarily Mayday will hitchhike with the goal be adopted out to select youngsters of visiting all 50 states in the U.S. and within the CSRA to accompany For details on the 10 different countries. She will hitch them on their family vacation. Mayday Mascot Students first through eighth grade Program with interest in participating in the please visit program must submit a one page www.FlyAGS.com/Mayday essay stating why they believe Little or call Lauren Smith, AGS’s Miss Mayday should accompany Communications Manager them on their family’s next vacation. at (706) 798-3236. Holiday Spirit • Holiday ExoduS • Military HoSpitality facElift WintEr 2014 Mobile Boarding Passes Make Travel Easy at AGS! Due to the influx of requests for digital boarding passes electronic boarding pass upon arrival. -

Parker Review

Ethnic Diversity Enriching Business Leadership An update report from The Parker Review Sir John Parker The Parker Review Committee 5 February 2020 Principal Sponsor Members of the Steering Committee Chair: Sir John Parker GBE, FREng Co-Chair: David Tyler Contents Members: Dr Doyin Atewologun Sanjay Bhandari Helen Mahy CBE Foreword by Sir John Parker 2 Sir Kenneth Olisa OBE Foreword by the Secretary of State 6 Trevor Phillips OBE Message from EY 8 Tom Shropshire Vision and Mission Statement 10 Yvonne Thompson CBE Professor Susan Vinnicombe CBE Current Profile of FTSE 350 Boards 14 Matthew Percival FRC/Cranfield Research on Ethnic Diversity Reporting 36 Arun Batra OBE Parker Review Recommendations 58 Bilal Raja Kirstie Wright Company Success Stories 62 Closing Word from Sir Jon Thompson 65 Observers Biographies 66 Sanu de Lima, Itiola Durojaiye, Katie Leinweber Appendix — The Directors’ Resource Toolkit 72 Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy Thanks to our contributors during the year and to this report Oliver Cover Alex Diggins Neil Golborne Orla Pettigrew Sonam Patel Zaheer Ahmad MBE Rachel Sadka Simon Feeke Key advisors and contributors to this report: Simon Manterfield Dr Manjari Prashar Dr Fatima Tresh Latika Shah ® At the heart of our success lies the performance 2. Recognising the changes and growing talent of our many great companies, many of them listed pool of ethnically diverse candidates in our in the FTSE 100 and FTSE 250. There is no doubt home and overseas markets which will influence that one reason we have been able to punch recruitment patterns for years to come above our weight as a medium-sized country is the talent and inventiveness of our business leaders Whilst we have made great strides in bringing and our skilled people. -

Bus Schedules and Routes

City of Simi Valley Transit City of Simi Valley Transit provides a convenient We’ve Got Connections! and inexpensive way to travel in and around City of Simi Valley Transit is pleased to provide the City. Modern air-conditioned buses transport connections with other major transit systems: you in comfort to most major points of interest: ADA/Dial-A-Ride. 805-583-6464 shopping, schools, parks, public buildings and more! Amtrak Info: . 800-872-7245 LA Metro Information: ......323-466-3876 To fully enjoy the benefits of using the Metrolink: . 800-371-5465 buses, please remember: Moorpark City Transit: . .805-517-6315 • Food an beverages are not allowed on the TDD Information ...........800-735-2929 buses. Thousand Oaks Transit ......805-375-5467 • Please extinguish all smoking materials before VCTC:. 800-438-1112 boarding a bus. Free transfers are available upon request to L A • Radios, tape recorders, and electronic devices Metro and VCTC. must be turned off when boarding a bus. Headphones are allowed. All buses are wheelchair accessible. It is recommended that passengers call prior to • Drivers cannot make change. Please be starting a trip to confirm the closest bus stop prepared to pay the EXACT FARE. location. All buses are equipped with bike racks. • For Lost & Found items, call City of Simi Valley Transit at (805) 583-6456. Items may Fares be retrieved from the Simi Valley Police Full Fare Department Monday through Friday, 8:00 a.m. Single Trip. $1.50 to 4:00 p.m. Unlimited Day Pass . $5.00 • Bus Stops are located approximately ¼ to ½ 21-Ride Pass .....................$25.00 mile apart along routes within Simi Valley. -

When the Wheels on the Bus Stop Going Round and Round: Occupational Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities in Public Transportation

February 2015 errata On May 28, 2015, a correction was made to paragraph four under “BLS survey of occupational injuries and illnesses” in this article. The sentence, as originally published, incorrectly identified the cost of security cameras on buses as $18,000 per camera rather than per bus. When the wheels on the bus stop going round and round: occupational injuries, illnesses, and fatalities in public transportation Injuries and illnesses to bus drivers endanger not only their lives but also the lives of their passengers. In 2013, approximately 5,780 transit and intercity bus drivers experienced a days-away-from-work injury or illness while on the job. This article explores occupational injuries, illnesses, and fatalities to bus drivers and urban transit workers and examines how individual transit systems are collecting and analyzing their own employee safety data. The findings reveal that mass transit systems have taken steps to protect their employees from harm on the job and that injuries and illnesses to bus drivers and urban transit workers have declined in recent years. In October 2012, a Washington (DC) Metropolitan Area Gina Dowdell Hunter Transit Authority (WMATA) bus driver was hospitalized after [email protected] a rock was thrown through an open window and hit her Gina Dowdell Hunter is an economist in the Office 1 head while she was driving. In August 2013, a gunman of Safety, Health and Working Conditions, U.S. rushed on to a King County metro bus in downtown Seattle Bureau of Labor Statistics. and shot the driver during rush hour.2 These sorts of violent attacks involving bus drivers endanger not just the bus drivers but the passengers as well. -

Canadian Version

OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE AMALGAMATED TRANSIT UNION | AFL-CIO/CLC JULY / AUGUST 2014 A NEW BEGINNING FOR PROGRESSIVE LABOR EDUCATION & ACTIVISM ATU ACQUIRES NATIONAL LABOR COLLEGE CAMPUS HAPPY LABOUR DAY INTERNATIONAL OFFICERS LAWRENCE J. HANLEY International President JAVIER M. PEREZ, JR. NEWSBRIEFS International Executive Vice President OSCAR OWENS TTC targets door safety woes International Secretary-Treasurer Imagine this: your subway train stops at your destination. The doors open – but on the wrong side. In the past year there have been INTERNATIONAL VICE PRESIDENTS 12 incidents of doors opening either off the platform or on the wrong side of the train in Toronto. LARRY R. KINNEAR Ashburn, ON – [email protected] The Toronto Transit Commission has now implemented a new RICHARD M. MURPHY “point and acknowledge” safety procedure to reduce the likelihood Newburyport, MA – [email protected] of human error when opening train doors. The procedure consists BOB M. HYKAWAY of four steps in which a subway operator must: stand up, open Calgary, AB – [email protected] the window as the train comes to a stop, point at a marker on the wall using their index finger and WILLIAM G. McLEAN then open the train doors. If the operator doesn’t see the marker he or she is instructed not to open Reno, NV – [email protected] the doors. JANIS M. BORCHARDT Madison, WI – [email protected] PAUL BOWEN Agreement in Guelph, ON, ends lockout Canton, MI – [email protected] After the City of Guelph, ON, locked out members of Local 1189 KENNETH R. KIRK for three weeks, city buses stopped running, and transit workers Lancaster, TX – [email protected] were out of work and out of a contract while commuters were left GARY RAUEN stranded. -

Guidelines for the Safe Siting of School Bus Stops

Guidelines for the safe location of school bus stops 1. How are bus stops determined? Bus stops will be placed on public roadways and will avoid travel on private roads and/or driveways Bus routes are designed with buses traveling on main arterials with students picked up and dropped off at central locations. Visibility – Bus drivers need to have at least 500 feet of visible roadway to the bus stop. If there is not ample visibility (e.g. curve or hill) a “school bus stop ahead sign” is put in place before the stop in accordance with WAC 392-145-030 Bus drivers activate their school bus warning lights 300-100 feet before arriving at the bus stop, where the posted speed limit is 35 mph and under, and 500-300 feet before arriving at the bus stop where the posted speed limit is 35 mph and over. 2. Why are bus stops located at corners? Bus stops may be located at corners or intersections whenever possible. Corner stops are much more visible to drivers than house numbers. Students are generally taught to cross at corners rather than in the middle of the street. Traffic controls, such as stoplights or signs, are located at corners. These tend to slow down motorists at corners, making them more cautious as they approach intersections. The motoring public generally expects school buses to stop at corners rather than individual houses. Impatient motorists are also less likely to pass buses at corners than along a street. Cars passing school buses create the greatest risk to students who are getting on or off the bus. -

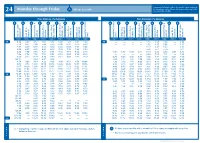

Monday Through Friday Mt

New printed schedules will not be issued if trips are adjusted Monday through Friday All trips accessible by five minutes or less. Please visit www.go-metro.com for the go smart... go METRO 24 most up-to-date schedule. 24 Mt. Lookout–Uptown–Anderson Riding Metro From Anderson / To Downtown From Downtown / To Anderson . 1 No food, beverages or smoking on Metro. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 2. Offer front seats to older adults and people with disabilities. METRO* PLUS 3. All Metro buses are 100% accessible for people 38X with disabilities. 46 UNIVERSITY OF 4. Use headphones with all audio equipment 51 CINCINNATI GOODMAN DANA MEDICAL CENTER HIGHLAND including cell phones. Anderson Center Station P&R Salem Rd. & Beacon St. & Beechmont Ave. St. Corbly & Ave. Linwood Delta Ave. & Madison Ave. Observatory Ave. Martin Luther King & Reading Rd. & Auburn Ave. McMillan St. Liberty St. & Sycamore St. Square Government Area B Square Government Area B Liberty St. & Sycamore St. & Auburn Ave. McMillan St. Martin Luther King & Reading Rd. & Madison Ave. Observatory Ave. & Ave. Linwood Delta Ave. & Beechmont Ave. St. Corbly Salem Rd. & Beacon St. Anderson Center Station P&R 11 ZONE 2 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 2 43 5. Fold strollers and carts. BURNET MT. LOOKOUT AM AM 38X 4:38 4:49 4:57 5:05 5:11 5:20 5:29 5:35 5:40 — — — — 4:10 4:15 4:23 — 4:35 OBSERVATORY READING O’BRYONVILLE LINWOOD 6. -

Attacks on Bus Operators and Passengers

Sensitive But Unclassified Material For Official Use Only Attacks on Bus Operators and Passengers Special Report Prepared by the ST, PT and OTRB ISACs May 4, 2015 Purpose In light of recent violent incidents targeting transit operators in numerous areas around the globe, the Surface Transportation (ST), Public Transportation (PT), and Over the Road Bus (OTRB) ISACs are providing this special report for your general security awareness. The application of any standards or guidance discussed herein is strictly voluntary. The practices implemented by rail, transit, and OTRB systems may be either more or less restrictive than any recommended practices or guidance given in this document. In some cases, federal and/or state regulations govern portions of public transit systems’ operations. In those cases, government regulations should take precedence over the information or guidance provided herein. Organizations should consult their own Agency’s/Organization’s policies and guidance before taking any actions based on the information presented in these documents. This document supplements guidance and analysis already provided in daily reports produced by the ST, PT, & OTRB ISACs. Of note, the last page of this report lists references for additional information. To contact an ST and PT ISAC analyst please call 866-784-7221, or email [email protected]. To contact an OTRB ISAC analyst please call 877-847-5510, or email [email protected] 1 Sensitive But Unclassified Material For Official Use Only Introduction The security of transit system and interstate bus operators has become an increasing concern for many metropolitan areas. Some attribute the perceived rise in attacks against operators as an artifact of increased reporting, but when that element of information is factored into the analysis, there still appears to be a notable surge in violent behavior targeting transit workers; particularly against bus drivers, who may remain the most vulnerable. -

Firstgroup Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2015 Contents

FirstGroup plc Annual Report and Accounts 2015 Contents Strategic report Summary of the year and financial highlights 02 Chairman’s statement 04 Group overview 06 Chief Executive’s strategic review 08 The world we live in 10 Business model 12 Strategic objectives 14 Key performance indicators 16 Business review 20 Corporate responsibility 40 Principal risks and uncertainties 44 Operating and financial review 50 Governance Board of Directors 56 Corporate governance report 58 Directors’ remuneration report 76 Other statutory information 101 Financial statements Consolidated income statement 106 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income 107 Consolidated balance sheet 108 Consolidated statement of changes in equity 109 Consolidated cash flow statement 110 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 111 Independent auditor’s report 160 Group financial summary 164 Company balance sheet 165 Notes to the Company financial statements 166 Shareholder information 174 Financial calendar 175 Glossary 176 FirstGroup plc is the leading transport operator in the UK and North America. With approximately £6 billion in revenues and around 110,000 employees, we transported around 2.4 billion passengers last year. In this Annual Report for the year to 31 March 2015 we review our performance and plans in line with our strategic objectives, focusing on the progress we have made with our multi-year transformation programme, which will deliver sustainable improvements in shareholder value. FirstGroup Annual Report and Accounts 2015 01 Summary of the year and