2016 National Human Settlements Conference Proceedings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acknowledgement to Reviewers 2014

Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 23 (2015) iiieviii Acknowledgement to Reviewers 2014 Stefan Lohmander Editor in Chief We are fortunate to have an outstanding group of reviewers who kindly volunteer their time and effort to review manuscripts for Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. They are critical team players in the continued success of the journal, ensuring a peer review process of the highest integrity and quality. I wish to thank those reviewers who provided their expertise in evaluating manuscripts for Osteoarthritis and Cartilage in 2014. Roy Aaron, Providence, United States Frank Beier, London, Canada Steven Abramson, New York, United States Kim Bennell, Parkville, Australia Ilana Ackerman, Parkville, Australia John Bertram, Calgary, Canada Douglas Adams, Farmington, United States Bruce Beynnon, Burlington, United States Michael Adams, Bristol, United Kingdom Sita Bierma-Zeinstra, Rotterdam, Netherlands Adetola Adesida, Edmonton, Canada Johannes Bijlsma, Utrecht, Netherlands Isaac Afara, Kuopio, Finland Trevor Birmingham, London, Canada Sudha Agarwal, Columbus, United States Sandip Biswal, Stanford, United States Bharat Aggarwal, Houston, United States Bernd Bittersohl, Düsseldorf, Germany Thomas Aigner, Coburg, Germany Jan Bjordal, Bergen, Norway Dawn Aitken, Hobart, Australia Francisco Blanco, A Coruna,~ Spain Michael Albro, New York, United States Esmeralda Blaney Davidson, Nijmegen, Netherlands Hamza Alizai, Valley Strean, United States Katerina Blazek, Stanford, United States Kelli Allen, Durham, United States Henning Bliddal, Frederiksberg, -

Essex Walker

May 2012 - Issue No. 339 DIAMOND JUBILEE INITIATIVE The Centurions have become well aware that with so many intermediate distance races now no longer on fixtures lists, it's becoming harder to complete 100 Miles OLYMPIC QUALIFYING in under 24 hours. Gone are those 100K/50 Miles races STANDARD ATTAINED along with nearly all 50K races/20 Miles/10 Miles and March's Dudince 50 Kilometres saw a quality field in which DOMINIC even 20K events. It's a huge leap from your local races KING (Colchester Harriers) recorded a personal best 4 hours 6 to the 100 Miles/24 Hours distance. The Centurions are minutes and 34 seconds when achieving 19th position among 45 promoting the benefits of participation in the Queen's finishers. 1st was Italian Alex Schwager in 3.40.48; and 13 beat 4 hours including Ireland's Brendan Boyce who came 7th in 3.57.53. Jubilee 60K walk (target is about 11 hours) on Sunday 45th man home was Hungary's Istvan Csaba in 5.38.52. A high 15th July over a circular route. This route has several number - 37 - recorded DNF's while 6 saw the red disc...including connections with transport hubs (bus/rail) for any who fellow Harrier DANIEL KING at 42K when on a 4.10 schedule. Fact is may have taken on too much. This could be a way of that Dominic's bettered our Olympic 'B' Standard, so is now available getting some "distance into your legs" on the build-up to for selection...and it ensures that Selectors do have a decision to be made. -

EOC PRESIDENT EOC Newsletter

EOC Newsletter No. 201 April 2020 MESSAGE FROM THE EOC PRESIDENT Dear colleagues, The value of staying connected while isolated during the COVID-19 pandemic cannot be understated. I am pleased to report that, following our first EOC Executive Committee meeting held by teleconference this month, the Olympic Movement of Europe is as close and interconnected as ever. Our day-to-day business, while certainly altered by the crisis, nevertheless continues unabated. There is nothing we were doing before the pandemic that we are not doing now in terms of our daily operations, and my sincere appreciation goes out to all the staff and administration at sports organisations across Europe for the excellent work you are doing in this regard. Staying connected and sharing best practices was one of the goals of our recent survey of the 50 European National Olympic Committees, which you can read more about in this newsletter and on the EOC website. The survey has allowed us to monitor and evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on sports around the continent. While the situation from country to country differs greatly depending on the local impact of coronavirus and other factors, two problems are universal: a lack of income due to the absence of sports events and limited access to sports facilities for elite athletes. Respondents provided us with a number of best practices, in particular with regard to assisting top athletes with their training routines, and I call on our ENOCs to continue sharing such knowledge for the benefit of all sports bodies in Europe. The COVID-19 pandemic is gradually improving, and we are finally seeing some liberalisation in terms of sanctioned sports activities. -

Another Year Down Nswccc T&F Championships, Sopac

HEEL AND TOE ONLINE The official organ of the Victorian Race Walking Club 2010/2011 Number 52 26 September 2011 VRWC Preferred Supplier of Shoes, clothes and sporting accessories. Address: RUNNERS WORLD, 598 High Street, East Kew, Victoria (Melways 45 G4) Telephone: 03 9817 3503 Hours : Monday to Friday: 9:30am to 5:30pm Saturday: 9:00am to 3:00pm Website: http://www.runnersworld.com.au/ ANOTHER YEAR DOWN This is our 52nd and last issue of the Heel and Toe Online for the year. It's quiet on the local front but there are a few results on which to report. NSWCCC T&F CHAMPIONSHIPS, SOPAC, SYDNEY, FRIDAY 16 SEPTEMBER The NSW Combined Catholic Colleges T&F Championships were held the weekend before last with Amy Bettiol (7:02.16) and Thomas Doyle 7:23.54 the two standout walkers. Boys 15+ 1500 Metre Race Walk 1. Murphy, Robert 15 M C C 7:36.00 Girls 15+ 1500 Metre Race Walk 1. Bettiol, Amy 16 Broken Bay 7:02.16 2. Denney, Hannah 16 C.G.S.S.S.A. 7:28.69 3. Gorman, Amelia 15 C.G.S.S.S.A. 7:40.06 4. Barendregt, Amanda 15 Parramatta 7:55.23 5. Martin, Samantha 15 C.G.S.S.S.A. 8:04.88 6. Shina, Isabella 16 Parramatta 8:13.46 Sund, Emily 18 Wollongong DQ Boys 12-14 1500 Metre Race Walk 1. Doyle, Thomas 14 M C C 7:23.54 2. Estrada, Patrick 13 Parramatta 8:18.60 Miller, Joseph 13 Bath Wil Forb DQ Martin, Timothy 13 Lismore DQ Girls 12-14 1500 Metre Race Walk 1. -

HEEL and TOE ONLINE the Official Organ of the Victorian Race Walking

HEEL AND TOE ONLINE The official organ of the Victorian Race Walking Club 2020/2021 Number 36 Tuesday 8+ June 2021 VRWC Preferred Supplier of Shoes, clothes and sporting accessories. Address: RUNNERS WORLD, 598 High Street, East Kew, Victoria (Melways 45 G4) Telephone: 03 9817 3503 Hours: Monday to Friday: 9:30am to 5:30pm Saturday: 9:00am to 3:00pm Website: http://www.runnersworld.com.au Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/pages/Runners-World/235649459888840 TIM’S WALKER OF THE WEEK My Walker of the Week is VRWC member Rhydian Cowley who has been added to the Australian Olympic team to contest the 50km walk in Japan. He joins Jemima Montag and Dane Bird-Smith who have already been pre-selected for the 20km. Further 20km walk additions are likely to take place when the qualification period for that event finishes on 29 th June. See the announcement at https://www.athletics.com.au/news/marathoners-selected-for-tokyo-2020-australian-olympic-team/. Well done Rhydian on your second Olympics. It is a just reward for all your hard work. I thought the MorelandStar (https://www.facebook.com/morelandstarnews/) summed it all up nicely LOCAL RESIDENT SELECTED FOR THE 2021 OLYMPICS The Australian Olympic Committee announced yesterday that Fawkner resident Rhydian Cowley has been selected for the Tokyo 2021 Olympic Games in the 50km Racewalk. If you walk along the Merri Creek trail, perhaps you’ve seen Rhydian as it’s where he does a lot of his training – particularly during lockdown. In addition to sessions at the gym, he says he walks between 105 to 150 kms per week. -

The Rio Review the Official Report Into Ireland's Campaign for the Rio 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games

SPÓRT ÉIREANN SPORT IRELAND The Rio Review The official report into Ireland's campaign for the Rio 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games RIO 2016 REVIEW Foreword The Olympic and Paralympic review process is an essential component of the Irish high performance system. The implementation of the recommendations of the quadrennial reviews has been a driver of Irish high performance programmes for individual sports and the system as a whole. The Rio Review process has been comprehensive and robust. The critical feature of this Review is that the National Governing Bodies (NGBs) took a greater level of control in debriefing their own experiences. This Review reflects the views of all the key players within the high performance system. Endorsed by Sport Ireland, it is a mandate for the NGBs to fully implement the recommendations that will improve the high performance system in Ireland. There were outstanding performances in Rio at both the Olympic and Paralympic Games. The Olympic roll of honour received a new addition in Rowing, with Sailing repeating its podium success achieved in Moscow 1980, demonstrating Ireland's ability to be competitive in multiple disciplines. Team Ireland has built on the success of Beijing and London, and notwithstanding problems that arose, Rio was a clear demonstration that Ireland can compete at the very highest levels of international sport. Sport Ireland is committed to the ongoing development of the Sport Ireland Institute and adding to the extensive facilities on the Sport Ireland National Sports Campus. These are real commitments to high performance sport in Ireland that will make a significant difference to Irish athletes who aspire to compete at the top level. -

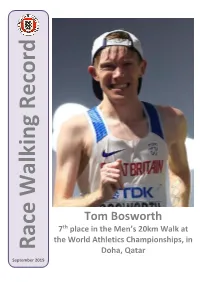

Tom Bosworth Callum Wilkinson

July 2019 Record Tom Bosworth Callum Wilkinson Tom Bosworth Cameron Corbishley Dominic King th 7 place in the Men’s 20km Walk at the World Athletics Championships, in Race Walking Doha, Qatar September 2019 Race Walking Record – September 2019 TARGETED EVENTS PROGRAMME RACE WALKING 2019-2020 Race Walk Training Camps • 17th November 2019 Sutcliffe Park Sports Centre, Eltham Road, London, SE9 5LW • 8th December 2019 Aldershot Military Stadium, Queen's Avenue, Aldershot, GU11 2JL th • 12 January 2020 Sutcliffe Park Sports Centre, Eltham Road, London, SE9 5LW • 17th-19th February 2020 Leeds Beckett University, Headingley Campus, Leeds, LS6 3QT Training days for invited athletes and coaches, from 10:00 -14:00 and largely practical in nature. They will focus on being the best athlete you can be from a technical, tactical, physical and mental perspective. To register, please email Andrew Drake, at [email protected] Invitation criteria: Athletes who competed in the 2019 ESAA Race Walking Championships; Athletes who competed in the 2019 EA U15/U17/U20/U23 Championships; Athletes who competed at 2019 British Trials - 5000m; Coach recommendations; Established endurance athletes who wish to try race walking. www.englandathletics.org Editor: Noel Carmody – Email: [email protected] Race Walking Record – September 2019 Women: Former world record-holder Rui Liang won in 4:23:26 ahead International Competition of her compatriot Maocuo Li in 4:26:40 and Italy’s European record- holder Eleonora Giorgi in 4:29:13. Portugal’s defending champion Ines Henriques was among those to drop out and Ukraine’s Olena Sobchuk claimed fourth place in 4:33:38. -

Definition, Evaluation, and Classification of Renal Osteodystrophy

http://www.kidney-international.org review & 2006 International Society of Nephrology Definition, evaluation, and classification of renal osteodystrophy: A position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) S Moe1, T Dru¨eke2, J Cunningham3, W Goodman4, K Martin5, K Olgaard6, S Ott7, S Sprague8, N Lameire9 and G Eknoyan10 1Indiana University School of Medicine and Roudebush VAMC, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA; 2Inserm Unit 507 and Division of Nephrology, Hoˆpital Necker, Universite´ Rene´ Descartes, Paris, France; 3The Royal Free Hospital and University College London, London, UK; 4Division of Nephrology, UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, USA; 5Division of Nephrology, St Louis University, St Louis, Missouri, USA; 6Department of Nephrology, Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; 7University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, Washington, USA; 8Evanston Northwestern Healthcare, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, USA; 9Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium and 10Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA Disturbances in mineral and bone metabolism are prevalent in Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a worldwide public health chronic kidney disease (CKD) and are an important cause of problem, with increasing prevalence and adverse outcomes, morbidity, decreased quality of life, and extraskeletal including progressive loss of kidney function, cardiovascular calcification that have been associated with increased disease, and premature death.1 -

Abstracts of the ECTS Congress 2017 ECTS 2017

Calcif Tissue Int (2017) 100:S1–S174 DOI 10.1007/s00223-017-0267-2 ABSTRACTS Abstracts of the ECTS congress 2017 ECTS 2017 13–16 May 2017, Salzburg, Austria 44th European Calcified Tissue Society Congress Published online: 11 May 2017 © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2017 Committees Scientific Programme Committee Chair: Claus-C. Glu¨er (Kiel, Germany) Co-Chairs: Richard Eastell (Sheffield, UK) – Clinical Co-Chair Martina Rauner (Dresden, Germany) – New Investigator Co-Chair Hans van Leeuwen (Rotterdam, Netherlands) – Basic Science Barbara Obermayer-Pietsch (Graz, Austria) – Local Organising Co-Chair Committee Chair Anna Teti (L’Aquila, Italy) – Incoming SPC Chair Members: Miep Helfrich (Aberdeen, UK) Bente Langdahl (Aarhus, Denmark) Gudrun Stenbeck (London, UK) Lorenz Hofbauer (Dresden, Germany) Willem Lems (Amsterdam, Netherlands) Franz Jakob (Wu¨rzburg, Germany) Stuart Ralston (Edinburgh, UK) Local Organising Committee Chair: Barbara Obermayer-Pietsch (Graz, Austria) Members: Hermann Agis (Vienna, Austria) Christian Muschitz (Vienna, Austria) Felix Eckstein (Salzburg, Austria) Martina Rauner (Dresden, Germany) Abstract Review Panel Each abstract was scored blind by a minimum of seven reviewers according to the following criteria: The scientific merit of the abstract Suitable sample size Adherence to instructions Originality of work The FishBone Workshop was held on May 12, 2017 in conjunction with the ECTS Annual Congress in Salzburg. The abstracts were reviewed by the organizers of the FishBone Workshop and publication was approved -

Chemistry 2015-2016 Newsletter

CHEMISTRY 2015-2016 NEWSLETTER Table of Contents CONTACT ADDRESS University of Rochester 3 Chemistry Department Faculty and Staff Department of Chemistry 404 Hutchison Hall 4 Letter from the Chair RC Box 270216 Rochester, NY 14627-0216 6 Donors to the Chemistry Department PHONE 10 In Memoriam (585) 275-4231 14 Alumni News EMAIL Saunders 90th Birthday [email protected] 16 Faculty Grants & Awards WEBSITE 18 www.sas.rochester.edu/chm 24 COR-ROC Inorganic Symposium FACEBOOK 25 CBI Retreat & Mat Sci Symposium www.facebook.com/UofRChemistry 26 Departmental Summer Picnic CREDITS 27 REU Program 2016 EDITOR 28 International Student Research Program Lynda McGarry 29 Pie in the Eye 30 Graduate Student Welcome Party LAYOUT & DESIGN EDITOR Deb Contestabile 31 Chemistry Welcomes Kathryn Knowles Yukako Ito (’17) 32 Faculty News REVIEWING EDITORS 64 Senior Poster Session Deb Contestabile 65 Commencement 2016 COVER ART AND LOGOS 67 Student Awards & News Deb Contestabile Yukako Ito (’17) 73 Doctoral Degrees Awarded 75 Postdoctoral Fellows PHOTOGRAPHS 76 Faculty Publications UR Communications John Bertola (B.A. ’09, M.S. ’10W) 82 Seminars & Colloquia Deb Contestabile Ria Tafani 89 Staff News Sheridan Vincent Thomas Krugh 93 Instrumentation UR Friday Photos Yukako Ito (’17) 95 Department Funds Ursula Bertram (‘18) Lynda McGarry 96 Alumni Update Form 1 2 PROFESSORS OF CHEMISTRY Faculty and Staff Robert K. Boeckman, Jr. Kara L. Bren Joseph P. Dinnocenzo ASSISTANT CHAIR FOR ADMINISTRATION James M. Farrar Kenneth Simolo Rudi Fasan Ignacio Franco ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT TO THE CHAIR Alison J. Frontier Barbara Snaith Joshua L. Goodman Pengfei Huo ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANTS William D. Jones Deb Contestabile Kathryn Knowles Robin Cooley Todd D. -

Irish Athletics Olympians, by Event

IAAF World Championships History IRELAND Venues: *1980 Sittard (NED) 1983 Helsinki (FIN), 1987 Rome (ITA), 1991 Tokyo (JPN), 1993 Stuttgart (GER), 1995 Gothenburg (SWE), 1997 Athens (GRE), 1999 Seville (ESP), 2001 Edmonton (CAN), 2003 Paris (FRA), 2005 Helsinki (FIN), 2007 Osaka (JPN), 2009 Berlin (GER), 2011 Daegu (KOR), 2013 Moscow (RUS), 2015 Beijing (CHN), 2017 London (GBR), 2019 Doha (QAT), 2021 Eugene (USA) Men 100m 1997 Neil Ryan 5h2 10.57 2011 Jason Smyth 5h2 10.57 200m 1997 Gary Ryan 2h6 20.69 8 QF 20.83 1999 Gary Ryan 5h10 20.86 1999 Paul Brizzel 4h5 21.02 2003 Paul Brizzel 5h2 20.75 5 QF 20.56 2005 Paul Hession 7h6 20.40 5 QF 21.69 2007 Paul Hession 2h5 20.46 1 QF 20.50 6 SF 20.50 2009 Paul Hession 2h3 20.66 3 QF 20.48 6 SF 20.48 2011 Paul Hession 4h3 21.02 Irish World Championship History - 1980-2017 1 400m 1997 Eugene Farrell 7h6 48.20 1999 Paul McBurney 8h2 46.87 2001 Tomas Coman 6h1 45.90 2003 Paul McKee 6h2 46.43 2007 David Gillick 3h2 45.35 6 SF 45.37 2009 David Gillick 2h1 45.54 4 SF 44.88 6 F 45.53 2013 Brian Gregan 6h2 46.04 7 SF 45.98 2017 Brian Gregan 3h 45.37 6 SF 45.42 800m 1995 David Matthews 4h7 1:46.52 1997 David Matthews 2h4 1:47.33 8 QF 1:46.66 1999 David Matthews 6h8 1:49.52 1999 James Nolan 4h3 1:46.38 7 SF 1:47.07 2001 Daniel Caulfield 4h2 1:47.23 2007 David Campbell 7h4 1:46.47 2009 Thomas Chamney 5h2 1:48.09 2013 Mark English 4h4 1:47.08 2013 Paul Robinson 6h1 1:48.61 2015 Mark English 5h3 1:46;69 5 SF 1:45.55 2017 Mark English 5h 1:48.01 1500m 1983 Frank O’Mara 3h2 3:40.53 11 SF 3:47.10 1983 Ray Flynn -

Heel and Toe 2018/2019 Number 11

HEEL AND TOE ONLINE The official organ of the Victorian Race Walking Club 2018/2019 Number 11 11 December 2018 VRWC Preferred Supplier of Shoes, clothes and sporting accessories. Address: RUNNERS WORLD, 598 High Street, East Kew, Victoria (Melways 45 G4) Telephone: 03 9817 3503 Hours: Monday to Friday: 9:30am to 5:30pm Saturday: 9:00am to 3:00pm Website: http://www.runnersworld.com.au Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/pages/Runners-World/235649459888840 TIM’S WALKERS OF THE WEEK My Walkers of the Week this time around are 16 year old Gwyllym Young of Canberra and 16 year old Corey Dickson of Melbourne. In horrendous conditions, they fought out the U18 5000m track walk at the Australian Schools Championships in Cairns last Friday evening. For the record, Gwyllym won with 22:11.7 (a PB of 1:34) and Corey was second with 22:13.8 (a PB of 1:21). The rain intensified as the evening progressed, but saved its worst for the U18 5000m walks, the last events of the evening. Sloshing through the puddles and almost lost in the heavy sheets of rain, the U18 boys showed strength and resilience that belied their age. The contrast could not be greater. Corey has had 33 races this year and had set PB after PB as the year has progressed, culminating in his 10km best of 46:58 at Fawkner Park last weekend. Gwyllym had recorded only 5 RWA walking races this year and had not competed over any significant distance since 21st July. But they both produced the goods when it counted most.