Libya: Transition and U.S. Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libya's Fight for Survival

LIBYA’S FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS September 2015 ! ! ! TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD 3 ESSAY ONE COMPETING JIHADIST ORGANISATIONS AND NETWORKS 6 Islamic State, Al-Qaeda, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and Ansar al-Sharia in Libya Stefano Torelli and Arturo Varvelli ESSAY TWO POLITICAL PARTY OR ARMED FACTION? 31 The Future of the Libyan Muslim Brotherhood Valentina Colombo, Giuseppe Dentice and Arturo Varvelli ESSAY THREE MAPPING RADICAL ISLAMIST MILITIAS IN LIBYA 53 Wolfgang Pusztai and Arturo Varvelli ESSAY FOUR THE EXPLOITATION OF MIGRATION ROUTES TO EUROPE 73 Human Trafficking Through Areas of Libya Affected by Fundamentalism Nancy Porsia ABOUT THE AUTHORS 87 BIBLIOGRAPHY 89 2 LIBYA’S FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS LIBYA’S FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL 3 DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS FOREWORD ! ! This publication is a compilation of four different essays, edited by Dr. Arturo Varvelli PhD, which from part of a series of studies undertaken by EFD to analyse the nature and spread of the phenomenon of radicalisation in the European Eastern and Southern neighbourhoods. It focuses on Libya and assesses the current situation on the ground through a number of diverse and varied prisms. It identifies patterns and trends as well as specific local and regional developments in order to provide a comprehensive overview of the situation of radicalisation in post-Ghadaffi Libya and the extent to which this may be contributing to regional as well as international instability Months of acute political turmoil in Libya following the fall of the Qaddafi regime, compounded by a weak national identity as well as legacies from the civil war in 2011 which ended Qaddafi’s 42-year rule, have resulted in Libya becoming a failed state with a strong radical Islamist presence. -

Libya's Fight for Survival

LIBYIA’S FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS September 2015 About the European Foundation for Democracy The European Foundation for Democracy is a Brussels-based policy institute dedicated to upholding Europe’s fundamental values of freedom and equality, regardless of gender, ethnicity or religion. Today these principles are being challenged by a number of factors, among them rapid social change as a result of high levels of immigration from cultures with different customs, a rise in intolerance on all sides, an increasing sense of a conflict of civilisations and the growing influence of radical, extremist ideologies worldwide. We work with grassroots activists, media, policy experts and government officials throughout Europe to identify constructive approaches to addressing these challenges. Our goal is to ensure that the universal values of the Enlightenment –religious tolerance, political pluralism, individual liberty and government by demo- cracy – remain the core foundation of Europe’s prosperity and welfare, and the basis on which diverse cultures and opinions can interact peacefully. About the Counter Extremism Project The Counter Extremism Project (CEP) is a not-for-profit, non-partisan, international policy organization formed to address the threat from extremist ideology. It does so by pressuring financial support networks, countering the narrative of extremists and their online recruitment, and advocating for effective laws, policies and regula- tions. CEP uses its research and analytical expertise to build a global movement against the threat to pluralism, peace and tolerance posed by extremism of all types. In the United States, CEP is based in New York City with a team in Washington, D.C. -

Origins of the Libyan Conflict and Options for Its Resolution

ORIGINS OF THE LIBYAN CONFLICT AND OPTIONS FOR ITS RESOLUTION JONATHAN M. WINER MAY 2019 POLICY PAPER 2019-12 CONTENTS * 1 INTRODUCTION * 4 HISTORICAL FACTORS * 7 PRIMARY DOMESTIC ACTORS * 10 PRIMARY FOREIGN ACTORS * 11 UNDERLYING CONDITIONS FUELING CONFLICT * 12 PRECIPITATING EVENTS LEADING TO OPEN CONFLICT * 12 MITIGATING FACTORS * 14 THE SKHIRAT PROCESS LEADING TO THE LPA * 15 POST-SKHIRAT BALANCE OF POWER * 18 MOVING BEYOND SKHIRAT: POLITICAL AGREEMENT OR STALLING FOR TIME? * 20 THE CURRENT CONFLICT * 22 PATHWAYS TO END CONFLICT SUMMARY After 42 years during which Muammar Gaddafi controlled all power in Libya, since the 2011 uprising, Libyans, fragmented by geography, tribe, ideology, and history, have resisted having anyone, foreigner or Libyan, telling them what to do. In the process, they have frustrated the efforts of outsiders to help them rebuild institutions at the national level, preferring instead to maintain control locally when they have it, often supported by foreign backers. Despite General Khalifa Hifter’s ongoing attempt in 2019 to conquer Tripoli by military force, Libya’s best chance for progress remains a unified international approach built on near complete alignment among international actors, supporting Libyans convening as a whole to address political, security, and economic issues at the same time. While the tracks can be separate, progress is required on all three for any of them to work in the long run. But first the country will need to find a way to pull back from the confrontation created by General Hifter. © The Middle East Institute The Middle East Institute 1319 18th Street NW Washington, D.C. -

Libya's Fight for Survival

LIBYA’S FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS September 2015 LIBYA’S FIGHTLIBYA’S FOR SURVIVAL: DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS About the European Foundation for Democracy The European Foundation for Democracy is a Brussels-based policy institute dedicated to upholding Europe’s fundamental values of freedom and equality, regardless of gender, ethnicity or religion. We work with grassroots activists, media, policy experts and government officials throughout Europe to identify constructive approaches to addressing these challenges. Our goal is to ensure that the universal values of the Enlightenment – political pluralism, individual liberty and government by democracy and religious tolerance – remain the core foundation of Europe’s prosperity and welfare, and the basis on which diverse cultures and opinions can interact peacefully. About the Counter Extremism Project The Counter Extremism Project is a not-for-profit, non-partisan, international policy organi- sation formed to address the threat from extremist ideology. It does so by pressuring financial support networks, countering the narrative of extremists and their online recruitment, and advo- cating for effective laws, policies and regulations. CEP uses its research and analytical expertise to build a global movement against the threat to pluralism, peace and tolerance posed by extremism of all types. In the United States, CEP is based in New York City with a team in Washington, D.C. LIBYA’S FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS September 2015 Edited by Arturo Varvelli -

Libya: Military Actors and Militias

Libya: military actors and militias By Francesco Finucci With special thanks to Lucia Polvanesi, for her editing work Photo: BRQ Network/Flickr The aftermath After Qaddafi's fall, about 200000 militiamen took to the streets. It was the end of a 40 years lasting regime. But it was also the first step towards the chaos: a country dominated by militias, fulfilled with weapons and characterized by harsh territories, where paratroops could hide themselves for months. Moreover, evidences suggest the use of this chaos in order to cover conflicts between rival tribes. Actions already blamed as war crimes. Hope is a fundamental element to be considered in new Libya, but fear is as well. What emerged from this study is a complicated scenario, much more than expected. On the other hand, requests are numerous and often genuine. The will to build a better place to live in came to light as well as the simple effort to gain power. Exploring this lively and intense underworld is not simple, even without being on the spot. Violence is part of this scenario as well as sense of the State. Sometimes they merge, sometimes they clash, but they never disappear. Probably, they won't do it for years, until Libya will be mature for military and political stability. After entering inside the last two years of Libyan history, we can't help hoping for this. Francesco Finucci Loyalty Name Flag/Symbol State-affiliated Libyan Army Force: 35000 soldiers1. القوات المسلحة الليبية Bodies The new army risen after Qaddafi's fall seems to be partially composed by former military staff, Allies: Libya Shield; and the detained equipment level is about the National Mobile Force; same as militias weaponry standard. -

The Development of Libyan Armed Groups Since 2014 Eaton, Alageli, Badi, Eljarh and Stocker Chatham House Contents

The Development of Libyan Armed of Libyan Since 2014 Groups The Development Research Paper Tim Eaton, Abdul Rahman Alageli, Emadeddin Badi, Mohamed Eljarh and Valerie Stocker Middle East and North Africa Programme | March 2020 The Development of Libyan Armed Groups Since 2014 Community Dynamics and Economic Interests Eaton, Alageli, Badi, Eljarh and Stocker Badi, Eljarh Alageli, Eaton, Chatham House Contents Summary 2 About this Paper 4 1 Introduction: The Development of Armed Groups Since 2014 7 2 Tripolitanian Armed Groups 15 3 Eastern Libya: The Libyan Arab Armed Forces 22 4 Armed Groups in Southern Libya 35 5 Mitigating Conflict Dynamics and Reducing the Role of Armed Groups in the Economy 51 About the Authors 63 Acknowledgments 64 1 | Chatham House The Development of Libyan Armed Groups Since 2014: Community Dynamics and Economic Interests Summary • Libya’s multitude of armed groups have followed a range of paths since the emergence of a national governance split in 2014. Many have gradually demobilized, others have remained active, and others have expanded their influence. However, the evolution of the Libyan security sector in this period remains relatively understudied. Prior to 2011, Libya’s internal sovereignty – including the monopoly on force and sole agency in international relations – had been personally vested in the figure of Muammar Gaddafi. After his death, these elements of sovereignty reverted to local communities, which created armed organizations to fill that central gap. National military and intelligence institutions that were intended to protect the Libyan state have remained weak, with their coherence undermined further by the post-2014 governance crisis and ongoing conflict. -

Perceptions of Security in Libya Institutional and Revolutionary Actors

[PEACEW RKS [ PERCEPTIONS OF SECURITY IN LIBYA INSTITUTIONAL AND REVOLUTIONARY ACTORS Naji Abou-Khalil and Laurence Hargreaves ABOUT THE REPORT This report assesses the popular legitimacy of Libya’s cur- rent security providers and identifies their vectors of local, religious, and legal legitimacy to better understand Libyan needs in terms of delivery of security services. Derived from a partnership between the United States Institute of Peace and Altai Consulting to carry out multifaceted research on security and justice in postrevolution Libya, the report develops a quantitative and qualitative research approach for gathering security and justice perceptions. It is accompanied by a Special Report on the influence of Libyan television on the country’s security sector. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Naji Abou-Khalil, a consultant with Altai Consulting, specializes in security sector reform and governance projects. Based in Tripoli since 2012, he has developed an in-depth knowledge of the political, security, and religious landscapes in Libya. Naji is also a cofounder of the Paris-based think tank Noria. Laurence Hargreaves is Altai Consulting’s Africa director and has directed qualita- tive and quantitative studies in Libya on topics related to perceptions of security and religion. Cover photo: Group of Libyan recruits travelling for military training outside Libya, 2013. Photo by Al Motasem Bellah Dhawi. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Ave., NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No. -

Libyan Political Economy

www.gsdrc.org [email protected] Helpdesk Research Report Libyan Political Economy Iffat Idris 18.07.2016 Question Give an update of key actors, dynamics and issues of Libyan political economy since the 2014 GSDRC report1 on the same topic. Contents 1. Overview 2. Key developments since 2014 3. Significant actors 4. Major dynamics and issues 5. References 1. Overview Much has changed in Libya since April 2014 – there have been significant political developments, new actors have emerged and others have been eclipsed. However, the fundamentals have not changed: Libya remains highly unstable and divided along multiple fracture lines, there are still a multitude of non- armed groups and even more armed groups, and relations between them continue to be extremely fluid. Given this, the literature on the country situation becomes quickly outdated. The main political development has been the establishment of two rival governments following contested elections in June 2014: a reconvened General National Congress (GNC) based in Tripoli and the House of Representatives (HoR) based in Tobruk. Coalitions of armed groups back each side: Operation Dignity opposed to Islamists and aligned to the HoR and Operation Libya Dawn coalition formed in response, comprising of Islamist groups and others supporting the GNC. In December 2015 the UN- backed Libya Political Agreement (LPA) was signed between representatives of both governments, setting up a Government of National Accord (GNA) with an executive Presidency Council. The Council established itself in Tripoli early this year (2016), but both the GNC and HoR persist – meaning Libya has three rival claimants to power. 1 Combaz, E. -

Human Trafficking and Smuggling on the Horn of Africa-Central Mediterranean Route

Human Trafficking and Smuggling on the Horn of Africa-Central Mediterranean Route February 2016 Fostering Resilience, Regional Integration and Peace for Sustainable Development Human Trafficking and Smuggling on the Horn of Africa-Central Mediterranean Route © Sahan Foundation and IGAD Security Sector Program (ISSP) You may reproduce this work in whole or in part without prior permission for non-commercial purposes, on the condition that you provide proper attribution of the sources in all copies. www.sahan.eu www.igadssp.org/ Front cover photo: www.ship-technology.com The information and views set out in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of IGAD, the IGAD Security Sector Program (ISSP) or Sahan Foundation. Neither IGAD nor Sahan Foundation nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. Table of Contents CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................5 Inception and Purpose of the Report..................................................................................................5 Methodology.............................................................................................................................................6 Literary Resources .................................................................................................................................6 Report Structure.....................................................................................................................................7 -

Proxy War Dynamics in Libya

PWP Confict Studies Proxy War Dynamics in Libya Jalel Harchaoui and Mohamed-Essaïd Lazib PWP Confict Studies The Proxy Wars Project (PWP) aims to develop new insights for resolving the wars that beset the Arab world. While the conflicts in Yemen, Libya, Syria, and Iraq have internal roots, the US, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and others have all provided mil- itary and economic support to various belligerents. PWP Conflict Studies are papers written by recognized area experts that are designed to elucidate the complex rela- tionship between internal proxies and external sponsors. PWP is jointly directed by Ariel Ahram (Virginia Tech) and Ranj Alaaldin (Brookings Doha Center) and funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Jalel Harchaoui is a research fellow at the Clingendael Institute in The Hague. His work focuses on Libya’s politics and security. Most of this essay was prepared prior to his joining Clingendael. Mohamed-Essaïd Lazib is a PhD candidate in geopolitics at University of Paris 8. His research concentrates on Libya’s armed groups and their sociology. Te views expressed are those of the authors alone and do not in any way refect the views of the institutions referred to or represented within this paper. Copyright © 2019 Jalel Harchaoui and Mohamed-Essaïd Lazib First published 2019 by the Virginia Tech School of Public and International Affairs in Association with Virginia Tech Publishing Virginia Tech School of Public and International Affairs, Blacksburg, VA 24061 Virginia Tech Publishing University Libraries at Virginia Tech 560 Drillfield Dr. Blacksburg, VA 24061 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21061/proxy-wars-harchaoui-lazib Suggested Citation: Harchaoui, J., and Lazib, M. -

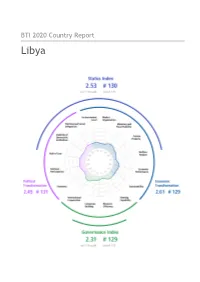

BTI 2020 Country Report — Libya

BTI 2020 Country Report Libya This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2020. It covers the period from February 1, 2017 to January 31, 2019. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of governance in 137 countries. More on the BTI at https://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2020 Country Report — Libya. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2020. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2020 | Libya 3 Key Indicators Population M 6.7 HDI 0.708 GDP p.c., PPP $ 20706 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 1.5 HDI rank of 189 110 Gini Index - Life expectancy years 72.5 UN Education Index 0.607 Poverty3 % - Urban population % 80.1 Gender inequality2 0.172 Aid per capita $ 65.6 Sources (as of December 2019): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2019 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2019. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary Libya has been affected by civil war since the 17 February Revolution in 2011, which led to the ouster of Colonel Muammar al-Qadhafi after 42 years in power. -

Instability and Insecurity in Libya

UNDP – Libya Instability and Insecurity in Libya Analysis This report has been prepared by consultants as part of a conflict analysis process undertaken by the United Nations Development Programme in Libya between March and September 2015. UNDP would like to acknowledge its partnership with the Peaceful Change Initiative, who conducted fieldwork that contributed to the preparation of this analysis. UNDP would also like to acknowledge the generous contribution of the Government of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, whose support funded the research and preparation of this analysis. Report prepared on behalf of UNDP by Tim Molesworth and David Newton. Executive Summary Four years after the 17 February 2011 revolution, Libya©s democratic transition process has faltered. The country saw the establishment of two rival governments in August 2014, leading to a sharp escalation in violence and effective paralysis in terms of services provided through the state. Extremist groups have been able to take advantage of the uncertainty in the country to strengthen their position and pose a growing threat to the state. At the same time, Libya©s complex network of relationships at the local level have led to local-level conflicts which maintain their own dynamics while influencing the broader political environment. Libya©s protracted instability has impeded Libya©s recovery and undermined the realisation of Libyans© political, social and economic rights. At least 3,700 Libyans are estimated to have been killed between June 2014 and August 2015. In August 2015, over 418,000 Libyans were estimated to be displaced due to conflict. Major damage has been done to infrastructure, while community access to basic services, including electricity, water, health care and education, is unreliable and worsening.