Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, Vol. Xvii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. ~Far O H 16

3940 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. ~fAR O H 16, By 1\Ir. SABATH: A bill (H. R. 10920) for the relief of N. Dak., urging the revival of the United States Grain Corpora William Chinsky ; to the Committee on Claims. tion and a stabilized price for farm products; to the Committee By 1\.Ir. TAYLOR of. Tennessee: A bill (H. R. 10921) granting on Agriculture. a pension to Frank McCoy ; to the Committee on Pensions. 4630. Also, petition of F. H. Schroeder and 21 other , of Bald- · Also, a bill (H. R. 10922) granting a pension to Polly Nelson; win, N. Dak., urging the revival of the United State Grain Cor to the Committee on Invalid Pensions. poration and a stabilized price on farm product ; to the Com Also, a bill (H. R. 10923) granting an increase -of pension to mittee on Agriculture. James B. King ; to the Committee on Pensions. 4631. Also, petition of J. F. Vavra and 65 others, of Stanton, N. Dak., urging the revival of the United State Grain Corpora tion and a stabilized price for farm products ; to . the Committee PETITIONS, ETC: on Agriculture. Under clnuse 1 of Rule XXII, petitions and papers were laid 4632. By Mr. TEMPLE: Petition of R. 1\f. Foster, of Racine, on the Clerk's desk and referred as follows: Beaver County, Pa., with reference to the bill providing for a 4612. By Mr. CRAMTON: Petition of John McCartney and bureau of civil aeronautics; to the Committee on Interstate and other residents of Mayville, Mich., protesting against the pas Foreign Commerce. -

World War II at Sea This Page Intentionally Left Blank World War II at Sea

World War II at Sea This page intentionally left blank World War II at Sea AN ENCYCLOPEDIA Volume I: A–K Dr. Spencer C. Tucker Editor Dr. Paul G. Pierpaoli Jr. Associate Editor Dr. Eric W. Osborne Assistant Editor Vincent P. O’Hara Assistant Editor Copyright 2012 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data World War II at sea : an encyclopedia / Spencer C. Tucker. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-59884-457-3 (hardcopy : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-59884-458-0 (ebook) 1. World War, 1939–1945—Naval operations— Encyclopedias. I. Tucker, Spencer, 1937– II. Title: World War Two at sea. D770.W66 2011 940.54'503—dc23 2011042142 ISBN: 978-1-59884-457-3 EISBN: 978-1-59884-458-0 15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit www.abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, LLC 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America To Malcolm “Kip” Muir Jr., scholar, gifted teacher, and friend. This page intentionally left blank Contents About the Editor ix Editorial Advisory Board xi List of Entries xiii Preface xxiii Overview xxv Entries A–Z 1 Chronology of Principal Events of World War II at Sea 823 Glossary of World War II Naval Terms 831 Bibliography 839 List of Editors and Contributors 865 Categorical Index 877 Index 889 vii This page intentionally left blank About the Editor Spencer C. -

Guide to the William A. Baker Collection

Guide to The William A. Baker Collection His Designs and Research Files 1925-1991 The Francis Russell Hart Nautical Collections of MIT Museum Kurt Hasselbalch and Kara Schneiderman © 1991 Massachusetts Institute of Technology T H E W I L L I A M A . B A K E R C O L L E C T I O N Papers, 1925-1991 First Donation Size: 36 document boxes Processed: October 1991 583 plans By: Kara Schneiderman 9 three-ring binders 3 photograph books 4 small boxes 3 oversized boxes 6 slide trays 1 3x5 card filing box Second Donation Size: 2 Paige boxes (99 folders) Processed: August 1992 20 scrapbooks By: Kara Schneiderman 1 box of memorabilia 1 portfolio 12 oversize photographs 2 slide trays Access The collection is unrestricted. Acquisition The materials from the first donation were given to the Hart Nautical Collections by Mrs. Ruth S. Baker. The materials from the second donation were given to the Hart Nautical Collections by the estate of Mrs. Ruth S. Baker. Copyright Requests for permission to publish material or use plans from this collection should be discussed with the Curator of the Hart Nautical Collections. Processing Processing of this collection was made possible through a grant from Mrs. Ruth S. Baker. 2 Guide to The William A. Baker Collection T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Biographical Sketch ..............................................................................................................4 Scope and Content Note .......................................................................................................5 Series Listing -

The Electrical Experimenter'' —

is-oo V'^l SEPT. OVER nO'^^J? 19 18 1 75 15 CTS. Electrical ILLUST. Experimenter SCIENCE AND INVENTION REG. U. S. PAT. OFF. i »J.ASSQING AEROPLANES WITH FLAME AND BOMB SEE PAGE. 300 LARGEST CIRCULATION OF ANY ELECTRICAL PUBLICATION . — ! — BE A CERTIFICATED ELECTRICIAN YOUNG MEN The country needs more trained, graduate electricians. Thousands have gone into the Govern- LulOI I^XFIMI EjIi rnent service and there is such an unusual demand for competent electrical men that I am making a wonder- ful offer at this time. HERE IS YOUR OPPORTU- NITY! I want to send you my splendid offer now. Don't hesitate because of age or experience. Young men, boys and old men must now fill the gaps and l:cep business going. DO YO'UR PART. Pre- pare yourself for a real position, by my Home Study Course in Practical Electricity. I am Chief Engineer of the Chicago Engineering Works. I have trained thousands of men and can help you better than anybody else. We also have large, splendidly-equipped shops where you can come at any time for special instruction without charge. No other correspondence school can give you this. SPECI.'\L OFFER: Right now I am giving a big, valuable surprise that I cannot explain here, to every student who answers this ad. Write today H62£ to n0022 a Week Go after some real money. Qualify for one of the thousands of splendid positions open. All you need to start is a few months snappy, prac- tical mstvuction from a competent engineer. Come tome NOIV. -

Fire-Fighting Training at MM&P

Vol. 41, No. 4 The International July – August Marine Division 2005 of ILA/AFL-CIO Official Voice of the International Organization of Masters, Mates & Pilots Fire-Fighting Training at MM&P Manulani Christened Contracts With Sulphur Carriers, Shaver The Master, Mate & Pilot July – August 2005 - 1 - Vol. 41, No. 4 July – August 2005 Table of Contents The Master, Mate & Pilot (ISSN 0025-5033) is the official voice President’s Letter 1 of the International Organization of Why your PCF contribution is so important Masters, Mates & Pilots (International Marine Division of the ILA), Company News 3 AFL-CIO. Published bimonthly at MM&P Headquarters, 700 Maritime Boulevard, MM&P vice presidents at Manulani christening; Linthicum Heights, MD 21090-1941. arbitration win for MM&P; contracts with Sulphur Telephone: (410) 850-8700 E-mail: [email protected] Carriers, Shaver; updates on APL, McAllister Internet: www.bridgedeck.org Periodicals postage paid at Linthicum Heights, News Briefs 5 MD, and additional offices. MM&P’s Glen Banks meets with Rep. Ben Cardin; POSTMASTER—Please send changes to: The Master, Mate & Pilot elegant watches are new PCF gift; Horizon Hawaii port 700 Maritime Boulevard Linthicum Heights, MD 21090-1941 call; maritime union consensus on TWIC card; NSPS Timothy A. Brown update; Moment of Remembrance on E-Ships Endurance Chairman, Editorial Board Lisa Rosenthal Communications Director Washington Observer 8 MM&P-supported bills make progress in INTERNATIONAL OFFICERS Timothy A. Brown. President 109th Congress; U.S. Coast Guard has controversial Glen P. Banks. Secretary-Treasurer new credentialing proposal VICE PRESIDENTS Steve Demeroutis. United Inland Into the Fire 12 Bob Groh. -

September 18 and 19.From Sanitary Inspector Porter

PUBLIC HEALTH REPORTS. UNITED STATES. Yellow fever in the United State&. The total number of cases and deaths officially reported at New Orleans is as follows: Cases, 2,907; deaths, 378 from July 21 to Sep- temnber 27, inclusive. Daily reports from New Orleans: Date. Cases. Deaths. New foci. September 21 ............I. 36 4 9 September 22 .................. 37 4 15 September 23 .... 45 6 11 September24 ...........,,,.,,.,.!.24 2 8 September 25 ......... : ..................... 37 3 7 September26 ..... ...................................................... 315 7 September27 ............................. 19 5 5 September 15. Reports from Passed Assistant Surgeon Francis, Mobile, show that 136 fruit cars were disinfected under his supervision at that place from August 31 to September 13. September 18. From Passed Assistant Surgeon von Ezdorf, Tallulah, La.: Nine new cases, no deaths for 17th; ten cases, one death to-day. Some of new cases are reported from near-by plantations. Oiling in whole town was done again to-day; fumigation of town completed except few houses with sick and some vacant residences. Fumigation of near-by plantations will be done to-morrow. Refumiga- tion of whole town can be begun Wednesday. Comparatively few mosquitoes left. September 18 and 19. From Sanitary Inspector Porter, Pensacola, Fla.: No new cases to-day; no deaths; total cases to date 43; deaths to date 9; dis- charged 29; under treatment 5. * * * One new case to-day; no deaths; cases to date 44; deaths to date 9; discharged to date 32; under treatment 3. Conditions look encouraging. September 18 and 19. Surgeon Guiteras reported from Vicksburg, Miss.: Five new cases and 1 death to-day. -

Game Notes Week of Sept24.Indd

2012 MEN’S SOCCER Weekly Release Contact: Stacey Brann • (412) 383-8650 • [email protected] •www.pittsburghpanthers.com • Athletic Media Relations; 3719 Terrace Street; Pittsburgh, PA 15261 University of Pittsburgh Panthers PANTHERS SCHEDULE (6-1-2, 0-1-0 Big East) (6-1-2, 0-1-0 Big East) Tuesday, Sept. 25 - Navy Midshipmen (4-2-1, 1-0-0 Patriot League) Sat. Aug. 18 Marshall (exhibition) W, 3-2 Ambrose Urbanic Field, Pittsburgh (PITT PANTHERS TV) Mon. Aug. 20 California (PA) (exhibition) T, 2-2 Fri. Aug. 24 vs. Niagara (at Duq) T, 2-2 Saturday, Sept. 29 - Georgetown Hoyas (8-0-1, 1-0-0 Big East) Sun. Aug. 26 vs. Howard (at Duq) W, 1-0 Ambrose Urbanic Field, Pittsburgh Sat. Sept. 1 Saint Francis (PA) T, 1-1 PITT/NIKE INVITATIONAL Fri. Sept. 7 IPFW W, 2-1 Pitt (6-1-2) continues its home stand with a pair of games this week. Pitt hosts the Midshipmen of Navy at 7 p.m. on Tuesday, Sept. 25 at Ambrose Sun. Sept. 9 Delaware W, 1-0 Urbanic Field at the Petersen Sports Complex. This is the sixth meeting Fri. Sept. 14 Northern Kentucky$ W, 3-2 between Pitt and Navy in program history. The Midshipmen lead the series Sun. Sept. 16 at Duquesne W, 2-1 0-5 and have captured wins in two of the past three meetings. Wed. Sept. 19 Robert Morris - Pitt Panthers TV W, 2-0 Navy posted a unbeaten week last week, beating then No. 20 George Mason Sat. Sept. -

Independent of the Sun Light, Energy & the American Home, 1913-1933 a Whole-House Exhibit at the Trail End State Historic Site, March 2007 - December 2007

Independent of the Sun Light, Energy & the American Home, 1913-1933 A Whole-House Exhibit at the Trail End State Historic Site, March 2007 - December 2007 Homeowners today take light, power and heat for granted, regardless of the time of day or month of the year. Prior to the advent of electricity and gas, however, humankind’s activities were largely constrained by the rising and setting of the sun, the time of which changed depending upon the season. It became science’s challenge to find a way to extend the light of day into the dark of night. “Back in the days when flickering candles and smoky lamps were the only means of lighting, men were striving to make themselves independent of the sun.” Better Homes & Gardens, 1927 Through careful study of period magazines, books and newspapers, and drawing upon the expertise of more modern researchers, Independent of the Sun seeks to show how the coming of electricity changed the American home in ways unimaginable to those who first fiddled with its powers. Illustrations are from the variety of period magazines donated to Trail End over the years. The Sun of Our Home Thanks to the efforts of Thomas Alva Edison, electricity first entered a select number of American homes in 1882 (Britain beat us by a few months, introducing electrical power to a INDEPENDENT OF THE SUN - 1 - WWW.TRAILEND.ORG small town in Surrey in late 1881). By 1913, just over sixteen percent of America’s urban homes had electric service. By the early 1930s, that number had risen to over 85 percent. -

History of a Future Ship 8

Number 308 • wiNter 2019 PowerAZINE OF E NGINE -P OWERED V ESSELS FROM ShipsTHE S TEAMSHI P H ISTORICAL S OCIETY OF A MERICA NUclear SHIP avannah S H istory of a Future Ship 8 PLUS Atoms For Power: Nuclear Propulsion in SAVANNAH 26 A Pipeline Pipe Dream: Tanker AMERICAN EXPLORER 38 Lives of the Liners: ANDREA DORIA 46 Thanks to All Who Continue to Support SSHSA January 8, 2019 Fleet Admiral ($50,000+) Admiral ($20,000+) Dibner Charitable Trust of Maritime Heritage Program Massachusetts The Family of Helen & Henry Posner Jr. Heritage Harbor Foundation The Estate of Mr. Donald Stoltenberg Ms. Mary L. Payne Benefactor ($10,000+) The Champlin Foundation Mr. Thomas C. Ragan Mr. Douglas Tilden Leader ($1,000+) Mr. Barry Eager Mr. Alexander Melchert Mr. John Spofford Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Ferguson Mr. W. John Miottel Jr. CAPT and Mrs. Terry Tilton Mr. Charles Andrews Mr. Henry Fuller Jr. Dr. Frederick Murray Mr. Peregrine White Mr. Jason Arabian Mr. and Mrs. Glenn Hayes CAPT and Mrs. Roland Parent Mr. Joseph White Mr. Douglas Bryan CAPT Philip Kantz Mr. Richard Rabbett Mr. James Zatwarnicki Jr. CDR Andrew Coggins Jr. Mr. Stephen Lash Mr. Stephen Roberts Mr. Ian Danic Mr. Don Leavitt Mr. Kenneth Schaller Mr. William Donnell Mr. William McLin Mr. and Mrs. James Shuttleworth Mr. Thomas Donoghue and Mr. Samuel J. McKeon Mr. Howard Smart Mr. Donald Eberle Mr. Jeff Macklin Mr. Richard Scarano Sponsor ($250+) Mr. Andrew Edmonds Mr. and Mrs. Jack Madden Schneider Electric North American Mr. Ronald Amos Exxon Mobil Foundation Mr. Ralph McCrea Foundation Mr. -

Ohio Stingrays Analytics Report.Xlsx

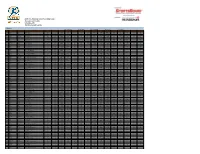

2015 Ohio Stingrays Classic Recruiting Camp Thursday, July 9, 2015 Columbus, OH The Ohio State University All Positions Overhand Throw Ball Exit Speed Pro Agility Shuttle 20 Yd Sprint Grip Strength # Last First Club Team Primary Position State GY/Class OH 1 OH 2 Ball Exit 1 Ball Exit 2 Pro Agil 1 Pro Agil 2 20-Yd 1 20-Yd 2 Grip (L)-1 Grip (L)-2 Grip (R)-1 Grip (R)-2 23 Weber Morgan KC Xplosion SS IL 2017 62 59 62 54 5.025 4.869 2.924 2.994 71 65 77 66 25 Bales Kristen Ohio Classics '99 CF OH 2017 56 55 57 58 5.251 5.185 3.261 3.198 64 71 62 64 26 Hanlon Emilee WNY Diamond Girls CF NY 2018 57 57 40 63 4.931 5.093 2.93 2.759 52 52 65 69 27 Kashmiry Kennedy Ohio Classics 2B OH 2018 51 54 56 55 5.057 5.224 3.261 3.26 59 51 60 60 28 Minnich Allison Greenville 1B OH 2016 53 54 64 64 5.741 5.671 3.65 3.727 79 83 86 74 29 Ety Ali Ohio Classics '00 CF OH 2018 43 45 51 43 5.051 5.092 3.166 3.275 52 54 49 54 30 Tracy Shelby Ohio Glory 99 C OH 2018 54 54 63 61 5.831 5.805 3.423 3.306 52 53 64 64 31 Briggs Kaitlynn Ohio Stingrays Y2K C OH 2019 56 57 57 62 5.887 6.274 3.759 3.643 41 50 65 61 32 Cummins Allison Ohio Classics '99 C OH 2018 60 62 62 70 5.148 5.049 3.127 3.173 58 58 63 63 101 Block Maggie Team Combat 97 C OH 2016 55 56 58 62 5.718 5.602 2.869 3.439 52 58 59 65 101 Block Maggie Team Combat 97 C OH 2016 55 56 57 41 3.244 3.144 73 77 102 Bobos Haylee Rollin Thunder Gold C PA 2016 57 57 57 60 6.166 6.178 3.361 3.611 50 51 75 72 105 Petry Jazzlyn Ohio Hawks 18U-Gold C OH 2016 51 52 40 67 5.751 5.298 3.556 3.025 52 49 56 58 105 Petry Jazzlyn -

The Marine Vessel's Electrical Power System

IEEE PROCEEDINGS 2015 1 The Marine Vessel’s Electrical Power System: From its Birth to Present Day Espen Skjong1;2;3, Egil Rødskar3, Marta Molinas1, Tor Arne Johansen1;2 and Joseph Cunningham4 Abstract—The evolution of the use of electricity in marine propulsion into the picture. Also in this period, research on air vessels is presented and discussed in this article in a historical independent propulsion (AIP) for submarines has been started perspective. The historical account starts with its first commercial and ended with the first submarine with AIP in the period use in the form of light bulbs in the SS Columbia in 1880 for illumination purposes, going through the use in hybrid that followed the end of the war. Nuclear powered vessels propulsion systems with steam turbines and diesel engines and emerged in the end of the 50s and the first passenger liner to transitioning to our days with the first case of electric marine use alternating current was inaugurated in 1960 (SS Canberra), vessel entirely based on the use of batteries in 2015. Electricity 70 years after the invention of the alternating current motor. use is discussed not only in the light of its many benefits but also In the period 1956-1985, the power electronics revolution of the challenges introduced after the emergence of the marine vessel electrical power system. The impact of new conversion triggered by the disruptive solid-state technology, marked the technologies like power electronics, battery energy storage and point of departure towards a new era for marine vessels; the the dc power system on the trajectory of this development is era of the all-electric ships (AES). -

Did You Know

24 - EVENING HERALD, Wed., Sept. 10, 1980 Gloves off for Nov. 4 HARTFORD (UPI) - A spunky "A year and a third ago we thought District where Republican Marjorie Donahue said he had word that former legislator, the "A-Bomb Kid" we could do it. We did it,” said Anderson will face an uphill fight Feld supporters would throw their and two virtual political unknowns Gejdenson, who had hailed himself against Democratic Rep. William support to his campaign. Donahue Sunny the "people's candidate" when he put a record round of congressional Cotter, who also wasn't challenged. planned to kick off his campaig today Sunny today; fair entered the race even prior to Dodd's primary races behind them today In the 6th District, Republicans at Century Brass in Waterbury, \A /PA TH PD tonight; sunny Friday. and looked to more difficult contests announcement to seek the Senate accepted Nicholas Schaus' slogan to where several hundred workers may W C M i n C n Details on page 2. in November. seat. "send Schaus to the House," and lose their jobs because of a planned For three of the six candidates who Guglielmo, who had first been gave the consulting firm owner a shutdown. were victorious in the busiest day of designated the loser because of a more than 2-1 margin of victory over Republicans in greater New nominating primaries in state computer error, vowed to get right to Paul Rosenberg, a colorful author of Haven's 3rd District opted for the history Tuesday, the next round of work, hoping to prove himself what crossword puzzles.