Gondek, Garrison 05-31-12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Academic Perspectives

Journal of Academic Perspectives Religion, Politics, and Public Discourse: Bruce Springsteen and the Public Church of Roll Frederick L. Downing, Professor of Philosophy & Religious Studies, Valdosta State University and Jonathan W. Downing, Co-Director, Screaming Shih-Tzu Productions Abstract The thesis of this paper is that Bruce Springsteen’s art participates in a musical public square in which the outsider can come up close and overhear a dialogue that has been going on for centuries. Following the work of Robert Detweiler on religion and public life, this paper starts from the premise that the bard’s music, like literature, creates a type of public square or a form of public discourse where urgent matters of human survival, like the nature and nurture of a just state, are expressed, a call for social justice can be heard, and faith and hope for the future can be assimilated. Using the theory of Martin Marty on religion and civic life, the paper further describes Springsteen’s work as the creation of a “public church” beyond sectarian demand which is open to all and approximates, in his language, a true “land of hopes and dreams.” The paper uses the theory of Walter Brueggemann on the ancient church idea to demonstrate the nature and dimension of Springsteen’s “public church.” Using Brueggemann’s theory, Springsteen’s Wrecking Ball album is shown to have both a prophetic and priestly function. As a writer and performer, Springsteen demonstrates on this album and on the Wrecking Ball tour that he not only speaks truth to power, but attempts to create a sense of alternative vision and alternative community to the unjust status quo. -

Evaluating the Effectiveness of Postfire Rehabilitation Treatments

United States Department Of Agriculture Evaluating the Effectiveness Forest Service Of Postfire Rehabilitation Rocky Mountain Research Station Treatments General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-63 Peter R. Robichaud Jan L. Beyers September 2000 Daniel G. Neary Abstract Robichaud, Peter R.; Beyers, Jan L.; Neary, Daniel G. 2000. Evaluating the effectiveness of postfire rehabilitation treatments. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-63. Fort Collins: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 85 p. Spending on postfire emergency watershed rehabilitation has increased during the past decade. A west-wide evaluation of USDA Forest Service burned area emergency rehabilitation (BAER) treatment effectiveness was undertaken as a joint project by USDA Forest Service Research and National Forest System staffs. This evaluation covers 470 fires and 321 BAER projects, from 1973 through 1998 in USDA Forest Service Regions 1 through 6. A literature review, interviews with key Regional and Forest BAER specialists, analysis of burned area reports, and review of Forest and District monitoring reports were used in the evaluation. The study found that spending on rehabilitation has increased to over $48 million during the past decade because the perceived threat of debris flows and floods has increased where fires are closer to the wildland-urban interface. Existing literature on treatment effectiveness is limited, thus making treatment comparisons difficult. The amount of protection provided by any treatment is small. Of the available treatments, contour-felled logs show promise as an effective hillslope treatment because they provide some immediate watershed protection, especially during the first postfire year. Seeding has a low probability of reducing the first season erosion because most of the benefits of the seeded grass occurs after the initial damaging runoff events. -

Meet Me in the Land of Hope and Dreams Influences of the Protest Song Tradition on the Recent Work of Bruce Springsteen (1995-2012)

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Meet me in the Land of Hope and Dreams Influences of the protest song tradition on the recent work of Bruce Springsteen (1995-2012) Supervisor: Paper submitted in partial Dr. Debora Van Durme fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Nederlands- Engels” by Michiel Vaernewyck May 2014 Word of thanks The completion of this master dissertation would not have been possible without the help of several people that have accompanied me on this road. First of all, thank you to my loving parents for their support throughout the years. While my father encouraged me to listen to an obscure, dusty vinyl record called The River, he as well as my mother taught me the love for literature and music. Thanks for encouraging me to express myself through writing and my own music, which is a gift that money just cannot buy. Secondly, thanks to my great friends of the past few years at Ghent University, although they frequently – but not unfairly – questioned my profound passion for Bruce Springsteen. Also, thank you to my supervisor dr. Debora Van Durme who provided detailed and useful feedback to this dissertation and who had the faith to endorse this thesis topic. I hope faith will be rewarded. Last but not least, I want to thank everyone who proofread sections of this paper and I hope that they will also be inspired by what words and music can do. As always, much love to Helena, number one Croatian Bruce fan. Thanks to Phantom Dan and the Big Man, for inspiring me over and over again. -

![[MJTM 16 (2014–2015) 131–50] Lee Beach It Is a Divine Mystery, but It](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4271/mjtm-16-2014-2015-131-50-lee-beach-it-is-a-divine-mystery-but-it-1274271.webp)

[MJTM 16 (2014–2015) 131–50] Lee Beach It Is a Divine Mystery, but It

[MJTM 16 (2014–2015) 131–50] THE MINISTER AS ARTIST: BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN AND MINISTRY FORMATION Lee Beach McMaster Divinity College, Hamilton, ON, Canada It is a divine mystery, but it must be stated, that Christian ministry is God’s work.1 God is the one who accomplishes his purposes, and it is best for us human creatures to admit that we do not fully understand how it all works. No matter how well we perform, or how hard we try, it seems that there is very little we can do to bring about the transformation of those we are called to minister to. The work of transformation is profoundly the work of God. We scatter the seed, someone else may water it, but it is God who gives it any real growth (1 Cor 3:6). To not ac- knowledge this is foolish, because it is a fundamental reality when it comes to the work of Christian ministry. However, as part of the mystery of ministry, and just as surely as it is ul- timately up to God, there is a human component to ministry as well. While not much will happen unless God shows up and does his work, it is also true that not much will happen unless the ministering person shows up and faithfully does their work. It seems like this is the way that God has made it. This can be argued from at least two perspectives. First, Scripture provides us with a clear sense of the partnership that God intends to have with humanity in carrying out his work in this world. -

Sophie's World

Sophie’s World Jostien Gaarder Reviews: More praise for the international bestseller that has become “Europe’s oddball literary sensation of the decade” (New York Newsday) “A page-turner.” —Entertainment Weekly “First, think of a beginner’s guide to philosophy, written by a schoolteacher ... Next, imagine a fantasy novel— something like a modern-day version of Through the Looking Glass. Meld these disparate genres, and what do you get? Well, what you get is an improbable international bestseller ... a runaway hit... [a] tour deforce.” —Time “Compelling.” —Los Angeles Times “Its depth of learning, its intelligence and its totally original conception give it enormous magnetic appeal ... To be fully human, and to feel our continuity with 3,000 years of philosophical inquiry, we need to put ourselves in Sophie’s world.” —Boston Sunday Globe “Involving and often humorous.” —USA Today “In the adroit hands of Jostein Gaarder, the whole sweep of three millennia of Western philosophy is rendered as lively as a gossip column ... Literary sorcery of the first rank.” —Fort Worth Star-Telegram “A comprehensive history of Western philosophy as recounted to a 14-year-old Norwegian schoolgirl... The book will serve as a first-rate introduction to anyone who never took an introductory philosophy course, and as a pleasant refresher for those who have and have forgotten most of it... [Sophie’s mother] is a marvelous comic foil.” —Newsweek “Terrifically entertaining and imaginative ... I’ll read Sophie’s World again.” — Daily Mail “What is admirable in the novel is the utter unpretentious-ness of the philosophical lessons, the plain and workmanlike prose which manages to deliver Western philosophy in accounts that are crystal clear. -

Remembering a Congressman and His Efforts to Help Africa

08 March 2012 | MP3 at voaspecialenglish.com Remembering a Congressman and His Efforts to Help Africa AP Representative Donald Payne in New Jersey in 2009 JUNE SIMMS: Welcome to AMERICAN MOSAIC in VOA Special English. (MUSIC) I'm June Simms. On the program today, new music from "the Boss," Bruce Springsteen… And we go to Texas for a major livestock show and rodeo … But first, we remember longtime New Jersey Congressman Donald Payne, who died this week from cancer. (MUSIC) Donald Payne JUNE SIMMS: United States Congressman Donald Payne died of cancer this week at the age of seventy-seven. He is well known for his social and political activism, 2 especially concerning Africa. Donald Payne was the first African-American congressman to represent the state of New Jersey, and a former leader of the Congressional Black Caucus. In addition, he was the first African-American president of the Young Men's Christian Association, the Y.M.C.A. Before becoming involved in politics, Mr. Payne served as a public school teacher in New Jersey. He later used his position on the House of Representatives Education and the Workforce Committee to increase financing for education and healthcare. He was a top member and former chairman of the Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, and Human Rights. In that group, he urged to improve human rights in Africa and increase humanitarian assistance to the continent. He visited several African nations often, including Sudan. In two thousand two, he was a major force in writing the Sudan Peace Act. The Act provided efforts for food aid to the nation as well as work on settling the conflict. -

Abandoned-Inactive Mines on Lewis and Clark National Forest-Administered Land

Abandoned-Inactive Mines on Lewis and Clark National Forest-Administered Land Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Abandoned-Inactive Mines Program Open-File Report MBMG 413 Phyllis A. Hargrave Michael D. Kerschen Geno W. Liva Jeffrey D. Lonn Catherine McDonald John J. Metesh Robert Wintergerst Prepared for the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service-Region 1 Abandoned-Inactive Mines on Lewis and Clark National Forest-Administered Land Open-File Report MBMG 413 Reformatted for .pdf April 2000 Phyllis A. Hargrave Michael D. Kerschen Geno W. Liva Jeffrey D. Lonn Catherine McDonald John J. Metesh Robert Wintergerst Prepared for the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service-Region 1 Contents Page List of Figures ............................................................. iv List of Tables .............................................................. vi Introduction ...............................................................1 1.1 Project Objectives ..................................................1 1.2 Abandoned and Inactive Mines Defined ..................................2 1.3 Health and Environmental Problems at Mines ..............................2 1.3.1 Acid-Mine Drainage .........................................3 1.3.2 Solubilities of Selected Metals ..................................4 1.3.3 The Use of pH and SC to Identify Problems ........................5 1.4 Methodology ......................................................6 1.4.1 Data Sources ...............................................6 1.4.2 Pre-Field Screening -

Life of Buckskin N 752 Sam

IFE OF ■i . ■■ .. JJueKsKiri § am Maine State L ibrary, Augusta, Maine. BUCKSKIN SAM LIFE AND ADVENTURES OF Buckskin Sam. (SAMUEL H. NOBLE.) WRITTEN BY HIMSELF. JUL 9 1300 Printed by R u m fo r d F a l l s P u b l is h in g C o ., Rumford Falls, Maine, 1900. Copyright 1900 by Samuel H. Noble. PREFACE. In presenting this little book to the public, I do so, not from a feeling of pride, or for gain, but simply to satisfy a demand that my friends have made upon me. Many who have visited the different places of amusement where I exhibited, have asked for the history of my life. In order to satisfy them I have written this book. In reading this work my kind friends will see that the words of the immortal poet Shakespeare are indeed true, when he says: “There is a Divinity that shapes our ends, Rough hew them as we may.” The pages of this book may read like a romance, but believe me, every word is true. Here the simple recital of facts only proves the old adage true that “ Truth is stranger than fiction.” I am the public’s obedient servant, B u c k s k i n S a m . CONTENTS C H A P T E R I. P a g e . From Boyhood to Manhood. .................................................... 17 . Pranks at School.— First Adventure at Blunting. CHAPTER II. My First Vo y a g e ...................................................................20 Visit to Dismal Swamp.— A Plantation Husking and Dance.— A Storm at Sea.— Shipwreck and Danger.— Perilous Voyage Home. -

One Soul at a Time the Tradition of Rock-And-Roll in Small Communities of New Jersey

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Scienze del Linguaggio Tesi di Laurea One Soul at a Time The tradition of rock-and-roll in small communities of New Jersey. Relatrice Ch.ma Prof.ssa Daniela Ciani Forza Correlatore Ch.mo Prof. Marco Fazzini Laureanda Luna Checchini Matricola 962348 Anno Accademico 2012 / 2013 Index Introduction.................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Creating, spreading and breaking traditions........................................3 1.Meanings of 'tradition'..................................................................................... 3 American Tradition(s)................................................................................3 New Jersey's Folklore................................................................................ 5 Changing traditions....................................................................................7 2.Spreading traditions....................................................................................... 10 Tradition and globalization...................................................................... 11 3.Tradition and music........................................................................................15 Tradition, innovation, rebellion and globalization in music....................17 Chapter 2: The Jersey Shore artists........................................................................22 1.Southside Johnny........................................................................................... -

The Glass Castle: a Memoir

The Glass Castle A Memoir Jeannette Walls SCRIBNER New York London Toronto Sydney Acknowledgments I©d like to thank my brother, Brian, for standing by me when we were growing up and while I wrote this. I©m also grateful to my mother for believing in art and truth and for supporting the idea of the book; to my brilliant and talented older sister, Lori, for coming around to it; and to my younger sister, Maureen, whom I will always love. And to my father, Rex S. Walls, for dreaming all those big dreams. Very special thanks also to my agent, Jennifer Rudolph Walsh, for her compassion, wit, tenacity, and enthusiastic support; to my editor, Nan Graham, for her keen sense of how much is enough and for caring so deeply; and to Alexis Gargagliano for her thoughtful and sensitive readings. My gratitude for their early and constant support goes to Jay and Betsy Taylor, Laurie Peck, Cynthia and David Young, Amy and Jim Scully, Ashley Pearson, Dan Mathews, Susan Watson, and Jessica Taylor and Alex Guerrios. I can never adequately thank my husband, John Taylor, who persuaded me it was time to tell my story and then pulled it out of me. Dark is a way and light is a place, Heaven that never was Nor will be ever is always true ÐDylan Thomas, "Poem on His Birthday" I A WOMAN ON THE STREET I WAS SITTING IN a taxi, wondering if I had overdressed for the evening, when I looked out the window and saw Mom rooting through a Dumpster. -

The Wisdom of Jesus Environmentalism and the Bible by Rev

The Wisdom of Jesus Environmentalism and the Bible By Rev. Dr. Todd F. Eklof November 12, 2017 Almost 15 years ago to the day, I heard the nation’s high priest of the status quo, the fundamentalist preacher and cofounder of the Moral Majority, Jerry Falwell, in an unforgettable interview about Global Warming on CNN. “It was global cooling 30 years ago,” he scoffed, “…and it's global warming now. And neither of us will be here 100 years from now to know what it is. But I can tell you our grandchildren will laugh at those who predicted global warming. We'll be cooler by then, if the lord hasn't returned... The fact is that there is no global warming.” He then called global warming “a myth,” bragged about driving a GM Suburban, and concluded by urging “everyone to go out and buy an SUV today.” Though he’s now sitting on a cloud singing praises to God for all eternity (which sounds like hell to me), Falwell’s troubling beliefs about humanity’s relationship with the environment are still shared by many. These beliefs derive from the very real and widespread myth of anthropocentrism based on an interpretation of the Genesis story that places humanity at both the center and pinnacle of creation. As the only creature made in the “image and likeness” of the gods, the story goes, our very purpose, according to our creators, is to “fill the earth and subdue it; [and] have dominion over the fish of the sea, over the birds of the air, and over every living thing that moves on the earth.”1 Among theologians this is known as the “dominion mandate,” which some interpret to mean humans are commanded to control and exploit nature, while others argue it’s based on a bad translation of a couple of ancient Hebrew words. -

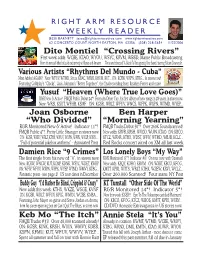

Right Arm Resource 061122.Pmd

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE WEEKLY READER JESSE BARNETT [email protected] www.rightarmresource.com 62 CONCERTO COURT, NORTH EASTON, MA 02356 (508) 238-5654 11/22/2006 Dito Montiel “Crossing Rivers” First week adds: WCBE, KTAO, WYOU, WSYC, KRVM, WBSD, Maine Public Broadcasting From his new self-titled cd, sold exclusvively at iTunes and Amazon Wrote and directed “A Guide To Recognizing Your Saints” starring Robert Downey Jr. Various Artists “Rhythms Del Mundo - Cuba” Most Added AGAIN! New: WFUV, WTMD, Sirius, KBAC, WBJB, KHUM, KUT... ON: KCRW, WXPN, KTBG... In stores now! Featuring Coldplay’s “Clocks”, Jack Johnson’s “Better Together”, the final recording from Ibrahim Ferrer and more Yusuf “Heaven (Where True Love Goes)” R&R New & Active! FMQB Public Debut 24*! From An Other Cup, his first album of new songs in 28 years, in stores now New: WRSI, KSUT, WFHB, KSMF ON: KGSR, WRLT, WFUV, WNCS, WFPK, WXPN, WTMD, WYEP... Joan Osborne Ben Harper “Who Divided” “Morning Yearning” R&R Monitored New & Active! Indicator 11*! FMQB Tracks Debut 50*! Over 260K Soundscanned! FMQB Public 4*! Pretty Little Stranger in stores now New adds: KRVB, KRSH, WVOD, WUIN, KTAO ON: KBCO, O N: KGSR, WXRV, WRLT, KTHX, WFUV, WXPN, WFPK, WYEP, WXPK... KTCZ, WRNR, KTHX, WDST, WFIV, WTMD, WBJB, KCLC... “Full of potential jukebox anthems” - Associated Press Red Rocks concert aired on XM all last week Damien Rice “9 Crimes” Los Lonely Boys “My Way” The first single from his new cd “9”, in stores now R&R Monitored 15*! Indicator #6! On tour now with Ozomatli New: KCRW, WNCW, KUT, KCMP, KDNK, WSYC, WDET, KWRP New adds: KSQY, KOHO, KBOM ON: WXRT, KBCO, KFOG, ON: WFIV, WFUV, WXPN, WFPK, WYEP, WTMD, WMVY, KTBG..