The War Years—1944 to 1946 by Dick Drury, 397-E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

[email protected] 44 Panzer-Armeeoberkommando 2

Panzer-Armeeoberkommando 2 (Second Panzer Army) 43 The predecessor of the Second Panzer Army, the XIX Motorized Corps (XIX. Armeekorps /mot./), was formed in May 1939, and took part as such in the Polish campaign. It fought in the West as Panzer Group Guderian (Panzergruppe Guderian), and in early May 1941, it was de- signated Panzer Group 2 (Panzergruppe 2). It fought as Panzer Group 2 in the early stages of the campaign on the eastern front. From July 28 to August 3, 194-1, it was known as Army Group Guderian (Armeegruppe Guderian), On October 5, 1941, it became the Second Panzer Army (Panzer-AOK 2). It continued to operate on the central sector of the eastern front until the middle of August 1943, when it was transferred to the Balkans for anti- guerilla operations. It was engaged in the Brod area in eastern Croatia in December 1944, and subsequently against the Soviets in southern Hungary. Commanders of the Army from May 1941 until its disbandment in May 1945 were Generals Heinz Guderian, Rudolf Schmidt, Walter Model, Lothar Rendulic, Franz Bbhme, and Maximilian de Angelis. Organization Index Abteilungen Dates Item I'o. Abteilung la Zustandsberichte Oct 24, 1939 - May 1, 1941 75118/8 T&tigkeitsbericht Jun 25 - Dec 24, 1940 10001/1 Anlagen zum T&tigkeitsbericht Jun 25 - Dec 17, 1940 10001/2-8 Meldungen Jul 12, 1940 - Jun 7, 1941 85424/5 Anlagen z. Tatigkeitsbericht* Dec 27, 1940 - Feb 27, 1941 10001/9-10 Anlage z. Tatigkeitsbericht Mar 1-28, 1941 10001/15 Anlagen z. Tfctigkeitsbericht Mar 25 - Jun 3, 1941 10001/19-21 Anlage z. -

Company A, 276Th Infantry in World War Ii

COMPANY A, 276TH INFANTRY IN WORLD WAR II FRANK H. LOWRY Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 94-072226 Copyright © 1991, 1994,1995 by Frank H Lowry Modesto, California All rights reserved ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This writing was started in 1945 in Europe following the cessation of hostilities that brought about an end to World War II. Many of the contributors were still together and their wartime experiences were fresh in their memories. It is the first hand account of the men of Company A, 276th Infantry Regiment, 70th Infantry Division which made history by living and participating in the bitter combat of the Ardennes-Alsace, Rhineland and Central Europe Campaigns. I humbly acknowledge my gratitude to the many veterans of those campaigns who provided valuable contributions to this book. A special note of appreciation goes to the following former soldiers of Company A who contributed significantly to this work. Without their input and guidance, this book could not have been written. Richard Armstrong, Hoyt Lakes, Minnesota Russell Causey, Sanford, North Carolina Burton K. Drury, Festus, Missouri John L. Haller, Columbia, South Carolina Daniel W. Jury, Millersburg, Pennsylvania Lloyd A. Patterson, Molalla, Oregon William J. Piper, Veguita, New Mexico Arthur E. Slover, Salem, Oregon Robert I. Wood, Dallas, Texas The assistance of Edmund C. Arnold, author and Chester F. Garstki, photographer of “The Trailblazers,” was very helpful in making it possible to illustrate and fit the military action of Company A into the overall action of the 70th Infantry Division. A word of thanks goes to Wolf T. Zoepf of Pinneberg, Germany for providing significant combat information from the point of view of those soldiers who fought on the other side. -

Standing Orders for the Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery Volume Ii

STANDING ORDERS VOLUME II (HERITAGE & LINEAGES) FOR THE ROYAL REGIMENT OF CANADIAN ARTILLERY May 2015 STANDING ORDERS FOR THE ROYAL REGIMENT OF CANADIAN ARTILLERY VOLUME II HERITAGE & LINEAGES PREFACE These Standing Orders for The Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery replace those issued August 2011. The only official version of these Standing Orders is in electronic PDF format found on www.candianartillery.ca. A formal review of Standing Orders will be conducted every five years. All Gunners must be familiar with the heritage and lineages of The RCA. Collectively, we must strive to uphold this heritage and to enhance the great reputation which The Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery has established over the years. To do less is to break faith with those Gunners who have preceded us and to diminish the inheritance of those who will follow. J.J. Selbie, OMM, CD J.M.D. Bouchard, CD Brigadier-General (Retired) Colonel Colonel Commandant Regimental Colonel i AMENDMENT LIST AL # Signature AL # Signature AL # Signature ii VOLUME II HISTORY & LINEAGES CONTENTS ARTICLE PAGE PREFACE……............................................................................................................... i CHAPTER 1 – A SHORT HISTORY OF THE RCA ...........……....................................... 1-1 101 Introduction...............………………............................................................................. 1-1 102 French Colonial Artillery 1534-1763……..................................................................... 1-1 103 English Colonial Artillery -

In Our Centennial Year of the Society, Another Great Reunion

In Our Centennial Year of the Society, Another Great Reunion By Henry Bodden – Editor ur 102nd Anniversary Left, entrance to Jekyll Soldiers Ball, and the Island Resort. 100th Anniversary of the Below, Gabe Guevarra O and Henry Bodden met Society of the Third Infantry in the lobby. Division returned to Fort Stewart, Georgia to celebrate these two events. Most guests to the reunion stayed at the Westin Hotel on the beach at Jekyll Island. Although the weather was overcast and drizzling for the Unfortunately, on Friday of weekend, it was nice to be on the November 15th, a transportation ocean for walks and sightseeing. glitch denied us a tour to the It was nice to reunite with friends Mighty Eight Museum tour, so and new acquaintances as every- some visited the area while oth- one checked in. On Thursday ers congregated in the November the 14th, registration Hospitality Room while awaiting began as members assembled in the much anticipated formal the Hospitality Room for snacks Soldiers Ball that night. So, at uniforms of our Fort Stewart sol- and fellowship. That night we all 5:00 p.m. there was a VIP recep- diers and all the beautiful ladies attended the President’s tion which was followed by a in their formal dress. It was a Reception Dinner with a wel- social hour. As a non-veteran and come and stirring speech by my first Soldiers Ball, I was real- Please turn to REUNION on page 4 Society President Toby Knight. ly impressed with all the dress A Visit With Col. -

World War Ii Veteran’S Committee, Washington, Dc Under a Generous Grant from the Dodge Jones Foundation 2

W WORLD WWAR IIII A TEACHING LESSON PLAN AND TOOL DESIGNED TO PRESERVE AND DOCUMENT THE WORLD’S GREATEST CONFLICT PREPARED BY THE WORLD WAR II VETERAN’S COMMITTEE, WASHINGTON, DC UNDER A GENEROUS GRANT FROM THE DODGE JONES FOUNDATION 2 INDEX Preface Organization of the World War II Veterans Committee . Tab 1 Educational Standards . Tab 2 National Council for History Standards State of Virginia Standards of Learning Primary Sources Overview . Tab 3 Background Background to European History . Tab 4 Instructors Overview . Tab 5 Pre – 1939 The War 1939 – 1945 Post War 1945 Chronology of World War II . Tab 6 Lesson Plans (Core Curriculum) Lesson Plan Day One: Prior to 1939 . Tab 7 Lesson Plan Day Two: 1939 – 1940 . Tab 8 Lesson Plan Day Three: 1941 – 1942 . Tab 9 Lesson Plan Day Four: 1943 – 1944 . Tab 10 Lesson Plan Day Five: 1944 – 1945 . Tab 11 Lesson Plan Day Six: 1945 . Tab 11.5 Lesson Plan Day Seven: 1945 – Post War . Tab 12 3 (Supplemental Curriculum/American Participation) Supplemental Plan Day One: American Leadership . Tab 13 Supplemental Plan Day Two: American Battlefields . Tab 14 Supplemental Plan Day Three: Unique Experiences . Tab 15 Appendixes A. Suggested Reading List . Tab 16 B. Suggested Video/DVD Sources . Tab 17 C. Suggested Internet Web Sites . Tab 18 D. Original and Primary Source Documents . Tab 19 for Supplemental Instruction United States British German E. Veterans Organizations . Tab 20 F. Military Museums in the United States . Tab 21 G. Glossary of Terms . Tab 22 H. Glossary of Code Names . Tab 23 I. World War II Veterans Questionnaire . -

The Savage Battle of the Colmar Pocket

Introduction After Strasbourg and Mulhouse had been liberated, the capitulation of the Colmar Pocket was believed to be close behind. Unfortunately, the facts would decide otherwise. Fighting was fierce and the strategies adopted were sometimes vague. Once Dijon had been liberated, the pace of the advance slowed and the towns of Belfort and Mulhouse would not fall until two months later. General Leclerc liberated Strasbourg at the same time, allowing him to fulfil the oath he had made at Kufra. With good reason, observers hoped that the liberation of the whole of Alsace would only be a matter of a few days, or, failing that, of a few weeks. It would, however, remain at the heart of communiqués for more than two months, filled as they were with new developments, suffering and loss of life. The Americans made strategic choices in this worldwide conflict, and Alsace was only one challenge among many others. General Eisenhower held the upper hand in all armed action. He had to reconcile the plans and requests of well-known leaders such as Bradley, Patton and Montgomery; Leclerc and de Lattre were merely direct subordinates of the head of SHAEF. General Leclerc was only a divisional commander and General de Lattre, for his part, had to make his requirements and plans known to General Devers, head of the 6th Army Group, who then submitted them to Eisenhower. Although the politicians had decision-making authority within this alliance, General de Gaulle hardly had the same influence over Roosevelt as Churchill. Luckily, Churchill supported his troublesome partner at decisive moments. -

Memorable Experiences by Mel J

Memorable Experiences by Mel J. Helmich, 925-C The 100th Infantry Division disembarked in Marseilles, France on 20 October 1944. The Division was rapidly marshalled and moved by echeloned truck convoy over 500 miles to the front near the French crystal center of Baccarat. The Division relieved elements of the 45th Infantry Division. First contact with the enemy occurred on 1 November 1944. The 100th Infantry Division had entered the Vosges Mountains campaign. During the second half of November, 1944 the 100th took part in the VI Corps, 7th Army penetration of the heavily-fortified German 19th Army Vosges Winter Line, thereby, helping to accomplish something never before accomplished by any army in history—the breach of the Vosges Mountains when defended. After practically destroying the freshly committed 708th Volks-Grenadier Division; the 100th wheeled north and pursued elements of the German 1st Army through the Low Vosges to the Maginot Line. Overcoming stiff resistance by the 261st Volks-Grenadier Division at Mouterhouse and Lemberg; elements of the Division seized Fort Schiesseck; a fourteen-story-deep fortress, replete with disappearing gun turrets and 12-foot-thick steel-reinforced concrete walls, in a four-day assault, from 17 to 20 December 1944. On New Year’s Eve 1945, the Germans initiated Operation NORDWIND, the last major German offensive in the west. After giving some ground initially, the 399th Infantry Regiment tenaciously defended Lemberg in the face of a determined assault by the entire 559th Volks-Grenadier Division and parts of the 257th. On the left, the 397th Infantry Regiment refused to be pushed out of the village of Rimling, where it blunted the attack of the vaunted 17th-SS Panzer-Grenadiers, the “Gotz von Berlichingen” Division. -

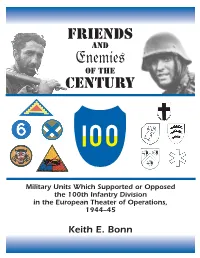

Military Units Which Supported Or Opposed the 100Th Infantry Division in the European Theater of Operations, 1944–45

Military Units Which Supported or Opposed the 100th Infantry Division in the European Theater of Operations, 1944–45 Keith E. Bonn Copyright 2000 by Keith E. Bonn. All rights reserved. Published by Aegis Consulting Group, PO Box 629, Bedford, PA 15522. Units Which Supported the 100th Infantry Division Although the 100th, like all US infantry divisions in WWII, was a combined arms organization with its own infantry, light and medium artillery, combat engineers, and mechanized cavalry troop, it was supported by a variety of separate Corps and Army assets in the execution of most of its missions. At various times, the 100th was supported by a vast array of corps and Army artillery units, and the list is too long to reproduce here. Suffice it to say that all artillery fires, including at times 155mm rifles and 8-inch howitzers from corps artillery and even 8-inch rifles and 240mm howitzers from Seventh Army artillery, were all controlled by the 100th’s DIVARTY, and their fires integrated with the DIVARTY fire support plans. None of these supporting artillery units were ever attached to the 100th, but only designated to fulfill varying reinforcing or direct support roles. This section provides information about the major combat outfits that were actually attached to the 100th, in part or entirely, throughout almost all of its com- bat in the ETO. By contributing unique battlefield capabilities and providing mobility or firepower beyond that available from integral Division resources, each of them played a vital role in the Division’s victories. The 100th Infantry Division was assigned to the Seventh Army throughout the Division’s combat operations. -

Boxcars and Burps Easy Does It

Major Bill Garden Boxcars and Burps Easy Does It Craig Davison Bill Law Major Bill Law Captain Craig Davison Baccarat, France, November 1944 Raon l’Etape, France, November 1944 St. Blaise, France, November 1944 Sparsbach, France, December 1944 Rothbach, France, December 1944 Mouterhouse, France, December 1944 Guising, France, December 1944 Rimling, France, January 1945 Hottwiller, France, January 1945 Holbach, France, March 1945 Bitche, France, March 1945 Waldhausen, France, March 1945 Pirmasens, Germany, March 1945 Neustadt, Germany, March 1945 Ludwigshaven, Germany, March 1945 Mannheim, Germany, March 1945 Weisloch, Germany, April 1945 Hillbach, Germany, April 1945 Heilbronn, Germany, April 1945 Bad Constantt, Germany, April 1945 Ulm, Germany, May 1945 Goppingen, Germany, May 1945 Stuttgart, Germany, August 1945 Ditzingen, Germany, October 1945 © Craig Davison, 2004 All rights reserved. Prologue This story of Company E covers its day-by-day of these. The infantryman wades ice-cold streams fight in France and Germany to the end of WWII or stinking swamps up to his armpits, and has no and victory. It describes the how, where, and chance of changing his clothes afterwards. The when of the history. This prologue tells both the result is utter exhaustion with blistered, bloody light and dark sides of the combat experience. feet, and chafed, bleeding skin. Combat impacts deeply on the life of a young Combat finds soldiers constantly seeking cover civilian-turned-soldier. It is an experience differ- and digging foxholes. Even without being hit by ent from any he will ever face . and one he will bullets or shrapnel, it means bruises, scrapes, forever remember. cuts, punctures, and sores. -

Most Underrated General of World War II: Alexander Patch by Keith E

Most Underrated General of World War II: Alexander Patch by Keith E. Bonn This article is excerpted from an upcoming book, Extreme War, by Terrence Poulos, due to be published by the Military Book Club. The article, written by Keith E. Bonn, draws not only from primary source documents, and also secondary source works such as The Story of the Century and Sandy Patch: A Biography of Lt. Gen. Alexander M. Patch, by William K. Wyant. Used with permission from the author. He was the first American commander to drive the Japanese off a major island; commanded soldiers from North America, Africa, and Europe in a stunningly successful invasion of the European mainland; led the first Allied units to successfully establish themselves along the Rhine; and defeated the last German offensive in the west. Other than Lucian Truscott, he was the American to command a division, corps, and field army in combat. He was the only American general to command large forces in three distinct theaters, namely, a division and corps in the Pacific Theater; an army in the Mediterranean Theater during the invasion of southern France; and an army in the European Theater. The field army he commanded fought over the most diverse and difficult terrain in all of western Europe, yet he never lost a major unit, and accomplished every mission assigned. Eisenhower rated him as “more valuable” than several of his much more well- known peers; Barry Goldwater said that he would have given his “right arm” to have served under him. He was deeply admired by his men, and lost his only son, an infantry captain serving under his command in combat. -

German Army Group G, 1 December 1944

German Army Group G 1 December 1944 Army Group Troops: IV Flak Corps 13th Flak Division (to 19th Army) 9th Flak Division (to 1st Army) 422nd Flak Company 2/631st (mot) Mapping Company 120th (mot) FA Kommando 352nd F.A. 717th G.F.P. 115th Fr. Lt. St 606th (mot) Signals Battalion 14th (mot) Signals Battalion 1025th (mot) Military Police Detachment Commander of the Rheinübergang 41st (mot) Pioneer Bridge Construction Battalion 145th (mot) Pioneer Bridge Construction Battalion 26th (mot) Brüko B 630th (mot) Brüko B 19th Army: Army Troops: 559th Heavy Panzerjäger Battalion 654th Heavy Panzerjäger Battalion 280th Assault Gun Battalion 2nd Armored Train Company 483rd (mot) Mapping Detachment 19th Sturm Battalion SS Kampfgruppe Army Pioneer School Battalion 317th Military Police Detachment 321st Division1 1/,2/,3/588th Infantry Regiment 1/,2/,3/589th Infantry Regiment 1/,2/,3/590th Infantry Regiment 1/,2/,3/321st Artillery Regiment 321st Division (Einheiten) Support Units A Pioneer Brigade Staff 926th Pioneer Staffel Staff 1st Pioneer Bridging Regiment 601st Ost Bridge Pioneer Battalion 746th Pioneer Battalion 926th Bridge Pioneer Battalion 39th (mot) Brüko B 2/406th (mot) Brüko B 2/422nd (mot) Brüko B Korück Brigade Märker Security Battalion 960th Security Battalion 1 Probably only a kampfgruppe strength unit. It was supposedly broken up earlier, but apparently was rebuilt. 1 835th Security Battalion 198th Security Battalion 200th Security Regiment Witte Security Regiment A Signals Brigade 532nd Signals Battalion LXIII Corps: Corps Troops: 1463rd Artillery Brigade 993rd Artillery Battalion 100th (mot) Reconnaissance Battalion 2nd Special Operations Infantry Battalion Unidentified Signals Battalion Böhme Freiwilliger (Volunteer) Regiment Aserbijan Legion North Caucasian Arb. -

The 45Th Infantry Division in the Vosges Campaign, 20 September 1944- 23 January 1945

Through the Frozen Mountains: The 45th Infantry Division in the Vosges Campaign, 20 September 1944- 23 January 1945 By Darrell Bishop A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY University of Central Oklahoma 2015 The thesis is dedicated to my loving wife Kari Bishop, for without her love and support, this thesis and the completion of my Masters program would not have been possible. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks are extended to the 45th Infantry Division Museum and to the Texas Military Forces Museum, who helped make the research of this thesis possible. Grateful appreciation is also extended to Mike Beckett (Historian for the 45th Infantry Division Museum), who gave me valuable help and feedback during the research phase. i Contents Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………………….. iii Chapter 1: Historiography: The Southern Prong of the Board Front . .. 1 Chapter 2: The Vosges Mountains, German and the 45th Infantry Division in 1944 . 21 Chapter 3: Moselle River Defense to the Colmar Pocket: 20 September to 31 December 1944 …………………………………………………………………………………45 Chapter 4: OPERATION NORDWIND: 1 to 23 January 1945…....…………………………………81 Conclusion ………………………………….…………………………………………………..96 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………100 Maps: Map 1………………. 6 Map 2………………. 8 Map 3………………. 24 Map 4………………..32 Map 5………………..35 Map 6………………. 37 Map 7………………. 47 Map 8……………… .49 Map 9………………. 53 Map 10..……………. 55 ii Map 11……………... 59 Map 12 …………….. 83 iii ABSTRACT OF THESIS University of Central Oklahoma Edmond, Oklahoma NAME: Darrell C. Bishop THESIS TITLE: Through the Frozen Mountains: The 45th Infantry Division in the Vosges Campaign, 20 September 1944- 23 January 1945 DIRECTOR OF THESIS: Stan Adamiak PAGES: 111 ABSTRACT: The purpose of this study is to examine the Vosges Mountain Campaign of World War II to better the fighting in southern France between the Wehrmacht and the Allies in particular the 45th Infantry Division.