Histories, Cultures, Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artificial General Intelligence and the Future of the Human Race Bryon Pavlacka

ARTIFICIAL GENERAL INTELLIGENCE AND THE FUTURE OF THE HUMAN RACE Bryon Pavlacka Artificial Intelligence is all around us. It manages be used against humanity. Of course, such threats are not your investments, makes the subway run on time, imaginary future possibilities. Narrow AI is already used diagnoses medical conditions, searches the internet, solves by the militaries of first world countries for war purposes. enormous systems of equations, and beats human players Consider drones such as the Northrop Grumman X-47B, at chess and Jeopardy. However, this “narrow AI,” designed an Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicle that is being tested for solving specific, narrow problems, is something by the US Navy (DefenseTech.org, 2011). That’s right, there distinctly different from Artificial General Intelligence, or is no pilot. Of course, the drone can be given orders, but “AGI”, true thinking machines with human-like general the exact way in which those orders are carried out will intelligence (Wang, Goertzel, & Franklin, 2008, p. v). While be left up to the drone’s Narrow AI system. Whether such AGI is not rigidly defined, it is often envisioned as being systems will ever be extended toward general intelligence self-aware and capable of complex thought, and has is currently unknown. However, the US military has shown BSJ been a staple of science fiction, appearing prominently in interest in producing and controlling generally intelligent popular films such as 2001: A Space Odyssey, Terminator, killing machines as well, as made evident by a paper called and I, Robot. In each of these films, the machines go “Governing Lethal Behavior” by Ronald C. -

Resume / CV Prof. Dr. Hugo De GARIS

Resume / CV Prof. Dr. Hugo de GARIS Full Professor of Computer Science Supervisor of PhD Students in Computer Science and Mathematical Physics Director of the Artificial Brain Laboratory, Department of Cognitive Science, School of Information Science and Technology, Xiamen University, Xiamen, Fujian Province, CHINA [email protected] http://www.iss.whu.edu.cn/degaris Education PhD, 1992, Brussels University, Brussels, Belgium, Europe. Thesis Topic : Artificial Intelligence, Artificial Life. Who’s Who Prof. Dr. Hugo de Garis, biographical entry in Marquis’s “Who’s Who in Science and Engineering”, USA, 2008. Editorial Board Memberships of Academic Journals (5) 1. Executive Editor of the “Journal of Artificial General Intelligence” (JAGI), an online journal at http://journal.agi-network.org (from 2008). 2. “Engineering Letters ” journal (International Association of Engineers, IAENG) 3. “Journal of Evolution and Technology ” (Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies, IEET) 4. “Evolutionary Computation ” journal (MIT Press) (former editorial board member, 1992-2007). 5. “Neurocomputing ” journal (Elsevier) (former editorial board member, 2000- 2006) Publications Summary Movie 1 Books 4 Journal Articles 27 Conference Papers 100 Book Chapters 15 Total 147 Movie (1) 6 minutes in the movie “Transcendent Man : The Life and Ideas of Ray Kurzweil”, Ptolemaic Productions, 2009. The movie discusses the rise of massively intelligent machines. Books (4) Hugo de Garis, “The Artilect War : Cosmists vs. Terrans : A Bitter Controversy Concerning Whether Humanity Should Build Godlike Massively Intelligent Machines”, ETC Publications, ISBN 0-88280-153-8, 0-88280-154-6, 2005. (Chinese version) “History of Artificial Intelligence –The Artilect War”, Tsinghua University Press, 2007. Hugo de Garis, “Multis and Monos : What the Multicultured Can Teach the Monocultured : Towards the Growth of a Global State”, ETC Publications, ISBN 978- 088280162-9, 2009. -

Perfection: United Goal Or Divisive Myth? a Look Into the Concept of Posthumanism and Its Theoretical Outcomes in Science Fiction

PERFECTION: UNITED GOAL OR DIVISIVE MYTH? A LOOK INTO THE CONCEPT OF POSTHUMANISM AND ITS THEORETICAL OUTCOMES IN SCIENCE FICTION by Rebecca McCarthy B.A., Southern Illinois University, 2009 M.A., Southern Illinois University, 2013 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Masters of Arts Department of English in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale December 2013 Copyright by Rebecca McCarthy, 2013 All Rights Reserved THESIS APPROVAL PERFECTION: UNITED GOAL OR DIVISIVE MYTH? A LOOK INTO THE CONCEPT OF POSTHUMANISM AND ITS THEORETICAL OUTCOMES IN SCIENCE FICTION By Rebecca McCarthy A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters in the field of English Literature Approved by: Dr. Robert Fox, Chair Dr. Elizabeth Klaver Dr. Tony Williams Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale 8/09/2013 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Rebecca McCarthy, for the Masters of English degree in Literature, presented on August 9, 2013, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: PERFECTION: UNITED GOAL OR DIVISIVE MYTH? A LOOK INTO THE CONCEPT OF POSTHUMANISM AND ITS THEORETICAL OUTCOMES IN SCIENCE FICTION MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. Robert Fox As science races to keep up with science fiction, many scientists are beginning to believe that the next step in human evolution will be a combination of human and machine and look a lot like something out of Star Trek. The constant pursuit of perfection is a part of the human condition, but if we begin to stretch beyond the natural human form can we still consider ourselves human? Transhumanism and posthumanism are only theories for now, but they are theories that threaten to permanently displace the human race, possibly pushing it into extinction. -

03 Garbowski.Pdf

ZESZYTY NAUKOWE POLITECHNIKI ŚLĄSKIEJ 2017 Seria: ORGANIZACJA I ZARZĄDZANIE z. 113 Nr kol. 1991 1 Marcin GARBOWSKI 2 John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin 3 Methodology of Science Department at the Faculty of Philosophy 4 [email protected] 5 A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE ASILOMAR AI PRINCIPLES 6 Streszczenie. The article focuses on the analysis of a set of principles 7 concerning the development of artificial intelligence, which were agreed upon a 8 the Asilomar international conference in January 2017. The declaration was 9 signed by leading scholar in the field of transhumanism and representatives of the 10 hi-tech enterprises. The purpose of the article is to lay out the core assumptions 11 behind this established set of norms that aim at the creation of so call „friendly 12 AI” as well as their practical implications. 13 Słowa kluczowe: Artificial intelligence, philosophy of technology, trans- 14 humanism 15 KRYTYCZNA ANALIZA ZASAD DOTYCZĄCYCH SZTUCZNEJ 16 INTELIGENCJI Z ASILOMAR 17 Abstract. Przedmiotem artykułu jest analiza zestawu zasad uzgodnionych na 18 międzynarodowej konferencji w Asilomar ze stycznia 2017 roku dotycząca 19 rozwoju sztucznej inteligencji. Sygnatariuszami porozumienia są czołowi badacze 20 tematyki związanej z transhumanizmem, ale także przedstawiciele koncernów z 21 sektora hi-tech. Celem artykułu jest przedstawienie założeń stojących za 22 deklarowanym szkicem norm, mających na celu wytworzenie tzw. Przyjaznej 23 sztucznej inteligencji oraz ich praktycznych konsekwencji. 24 Keywords: Sztuczna inteligencja, filozofia techniki, transhumanism 25 1. Introduction 26 When we consider the various technological breakthroughs which in the past decades 27 have had the greatest impact on a broad scope of human activity and which are bound to 28 increase it in the coming years, artificial intelligence certainly occupies a prominent place. -

Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence From open-encyclopedia.com - the free encyclopedia. Copyright © 2004-2005 This article is about modelling human thought with computers,. For other uses of the term AI, see Ai. Introduction Although there is no clear definition of AI (not even of intelligence), it can be described as the attempt to build machines that think and act like humans, that are able to learn and to use their knowledge to solve problems on their own.A 'by- product' of the intensive studies of the human brain by AI researchers is a far better understanding of how it works. The human brain consists of 10 to 100 billion neurons, each of which is connected to between 10 and 10,000 others through synapses. The single brain cell is comparatively slow (compared to a microprocessor) and has a very simple function: building the sum of its inputs and issuing an output, if that sum exceeds a certain value. Through its highly parallel way of operation, however, the human brain achieves a performance that has not been reached by computers yet; and even at the current speed of development in that field, we still have about twenty years until the first supercomputers will be of equal power. In the meantime, a number of different approaches are tried to build models of the brain, with different levels of success. The only test for intelligence there is, is the Turing Test. A thinking machine has yet to be built. 2. Why the current approach of AI is wrong These following thoughts do not deal with technical problems of AI, nor am I going to prove that humans are the only intelligent species (exactly the opposite, see section 5). -

Building Transhuman Immortals-Revised

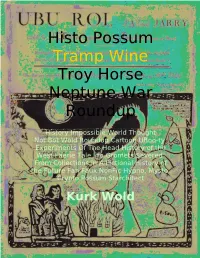

Histo Possum Tramp Wine Troy Horse Neptune War Roundup History Impossible World Thought Not Bot Wold Roundup Cartoon UBoo-ty Experiments Of The Head History of the West Faerie Tale Fro Gromets Severed From Collections in A Fictional History of the Future Fan Faux NonFic Hypno, Mysto, Crypto Possum Starchitect Kurk Wold 2 I. U-Booty Improvements I went down stairwells into caverns with no markings except codes, wandered, 10, 14 levels below the capitol. The walls went from stone to carved cave rock. Down there they stored artifacts, statues. I was stuck for hours until I found stairways leading up. None of them connected from one floor to the other. I kept walking to an elevator, pushed the up button, found myself in a non-public area. But I had my clearance tag. Asked by security, I told them I was lost. They escorted me to one of the main hallways. I made at least 14 levels below. Passages slope up and down from there where the hearts and livers are stored. I did not ask to investigate the spread of Ubu beyond earth, the beginning of weirdness, as if wierdness had a beginning and we all did not wake up to it individually while others slept to the song of opposite meaning. Rays of light popped off the original incarnation of Gulag and Babel as the same structure pounded itself into the ground. But on the tower, as one climbs higher and higher gravity decreases, and because it is constructed on the equator rotation causes gravitation to 3 disappear because of the distance from the center of the planet, but also from centrifugal force increasing proportionate to that distance. -

De GARIS ESSAYS

de GARIS ESSAYS Prof. Dr. Hugo de Garis DE GARIS ESSAYS CONTENTS The essays in this e-book are divided into the following categories – A) On the ARTILECT (Artificial Intellect) and Related Topics B) On GLOBA (the Global State) and Related Topics C) On CHINA D) On POLITICS E) On FERMITECH (Femto Meter Technology) and TOPOLOGICAL QUANTUM COMPUTING (TQC) F) On RELIGION G) On SOCIETY H) On EDUCATION ------------ A) On the ARTILECT (Artificial Intellect) and Related Topics A0) The Artilect War : Cosmists vs. Terrans : A Bitter Controversy Concerning Whether Humanity Should Build Godlike Massively Intelligent Machines A1) Building Gods or Building our Potential Exterminators? A2) Answering Fermi’s Paradox A3) Friendly AI : A Dangerous Delusion? A4) The Cyborg Scenario – Solution or Problem? A5) There are No Cyborgs A6) There Will Be No Cyborgs, Only Artilects : A Dialogue between Hugo de Garis and Ben Goertzel A7) Next Step : Now the Species Dominance Issue has Become Main Stream in the Media, the Next Step Should be Political A8) Seeking the Sputnik of AI : Hugo de Garis Interviews Ben Goertzel on AGI, Opencog, and the Future of Intelligence A9) What is AI Succeeds? The Rise of the Twenty-First Century Artilect A10) Merge or Purge? A11) Species Dominance Debate : From Main Stream Media to Opinion Polls A12) Species Dominance Poll Results A13) H+ers (Humanity Plus-ers) and the Artilect : Opinion Poll Results A14) Should Massively Intelligent Machines Replace Humanity as the Dominant Species in the Next Few Decades? A15) I am so Sick of American -

Artificial General Intelligence: Concept, State of the Art, and Future Prospects

Journal of Artificial General Intelligence 5(1) 1-46, 2014 Submitted 2013-2-12 DOI: 10.2478/jagi-2014-0001 Accepted 2014-3-15 Artificial General Intelligence: Concept, State of the Art, and Future Prospects Ben Goertzel [email protected] OpenCog Foundation G/F, 51C Lung Mei Village Tai Po, N.T., Hong Kong Editor: Tsvi Achler Abstract In recent years broad community of researchers has emerged, focusing on the original ambitious goals of the AI field – the creation and study of software or hardware systems with general intelligence comparable to, and ultimately perhaps greater than, that of human beings. This paper surveys this diverse community and its progress. Approaches to defining the concept of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) are reviewed including mathematical formalisms, engineering, and biology inspired perspectives. The spectrum of designs for AGI systems includes systems with symbolic, emergentist, hybrid and universalist characteristics. Metrics for general intelligence are evaluated, with a conclusion that, although metrics for assessing the achievement of human-level AGI may be relatively straightforward (e.g. the Turing Test, or a robot that can graduate from elementary school or university), metrics for assessing partial progress remain more controversial and problematic. Keywords: AGI, general intelligence, cognitive science 1. Introduction How can we best conceptualize and approach the original problem regarding which the AI field was founded: the creation of thinking machines with general intelligence comparable to, or greater than, that of human beings? The standard approach of the AI discipline (Russell and Norvig, 2010), as it has evolved in the 6 decades since the field’s founding, views artificial intelligence largely in terms of the pursuit of discrete capabilities or specific practical tasks. -

Download Neces- Sary Information Or Communicate with Other Cyborgs (Warwick 2003)

ARTIFICIAL SUPERINTELLIGENCE A FUTURISTIC APPROACH ARTIFICIAL SUPERINTELLIGENCE A FUTURISTIC APPROACH ROMAN V. YAMPOLSKIY UNIVERSITY OF LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY, USA Boca Raton London New York CRC Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business A CHAPMAN & HALL BOOK CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group 6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300 Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742 © 2016 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC CRC Press is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business No claim to original U.S. Government works Printed on acid-free paper Version Date: 20150205 International Standard Book Number-13: 978-1-4822-3443-5 (Paperback) This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, but the author and publisher cannot assume responsibility for the validity of all materials or the consequences of their use. The authors and publishers have attempted to trace the copyright holders of all material reproduced in this publication and apologize to copyright holders if permission to publish in this form has not been obtained. If any copyright material has not been acknowledged please write and let us know so we may rectify in any future reprint. Except as permitted under U.S. Copyright Law, no part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, transmit- ted, or utilized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publishers. For permission to photocopy or use material electronically from this work, please access www.copyright. -

Artificial Intelligence and Transhumanism: a Double Edged Utopian and Dystopian Discussion Of

Artificial intelligence and Transhumanism: A double edged utopian and dystopian discussion of human mortality and its relation to technology. Sylvester Elorm Coch Writing 3 Professor Alan Taylor March 10, 2018. Coch 2 The evolution of humanity is predicted by scientists to sooner or later experience a radical shift from the homo sapiens species to a more nuanced homo digitalis, a specie of robots with superhuman capabilities. Humanity’s dominance over the earth is confronted with several existential questions, often evoking an emotional cocktail of fear, excitement, pessimism, and hope. Several scholars have prophesied, in like fashion as did theoretical physicist, Stephen Hawking, in a 2014 interview with the BBC, that “the development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race." However, Ray Kurzweil, author of The Singularity Is Near, as well as other scholars, envisions a more utopian future, in which our human limitations of lifespan, cognition, and emotion are replaced with divine-like immortality, super-intelligence, prosperity, happiness and pleasure.1 For Kurzweil, “the essence of being human is not our limitations — although we do have many — it’s our ability to reach beyond our limitations.” 2 Even though there is a clear disparity in futuristic views, it is worth exploring how contemporary narratives and depictions of the potential of artificial intelligence reveal humanity’s innate longing for posthumanism, a state in which a person exists beyond the confinements of being human. Could artificial intelligence salvage humanity from our inherent weakness, liberate us from perpetual labor and suffering, and eliminate physical pain? Is artificial intelligence creating a techno-heaven for all of us? With these questions in mind, this paper explores the expressions of post-humanist cravings through the lens of literature and film, by revealing why these cravings exist in the first place and presents the thick dividing line between dystopian and utopian fascination with artificial intelligence. -

Safety Engineering for Artificial General Intelligence

MIRI MACHINE INTELLIGENCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE Safety Engineering for Artificial General Intelligence Roman V. Yampolskiy University of Louisville Joshua Fox MIRI Research Associate Abstract Machine ethics and robot rights are quickly becoming hot topics in artificial intelligence and robotics communities. We will argue that attempts to attribute moral agency and assign rights to all intelligent machines are misguided, whether applied to infrahuman or superhuman AIs, as are proposals to limit the negative effects of AIs by constraining their behavior. As an alternative, we propose a new science of safety engineering for intelligent artificial agents based on maximizing for what humans value. In particular, we challenge the scientific community to develop intelligent systems that have human-friendly values that they provably retain, even under recursive self-improvement. Yampolskiy, Roman V., and Joshua Fox. 2012. “Safety Engineering for Artificial General Intelligence.” Topoi. doi:10.1007/s11245-012-9128-9 This version contains minor changes. Roman V. Yampolskiy, Joshua Fox 1. Ethics and Intelligent Systems The last decade has seen a boom in the field of computer science concerned withthe application of ethics to machines that have some degree of autonomy in their action. Variants under names such as machine ethics (Allen, Wallach, and Smit 2006; Moor 2006; Anderson and Anderson 2007; Hall 2007a; McDermott 2008; Tonkens 2009), computer ethics (Pierce and Henry 1996), robot ethics (Sawyer 2007; Sharkey 2008; Lin, Abney, and Bekey 2011), ethicALife (Wallach and Allen 2006), machine morals (Wallach and Allen 2009), cyborg ethics (Warwick 2003), computational ethics (Ruvin- sky 2007), roboethics (Veruggio 2010), robot rights (Guo and Zhang 2009), artificial morals (Allen, Smit, and Wallach 2005), and Friendly AI (Yudkowsky 2008), are some of the proposals meant to address society’s concerns with the ethical and safety implica- tions of ever more advanced machines (Sparrow 2007). -

Artificial Intelligence Through the Eyes of the Public

Project Number: 030411-114414 - DCB IQP 1002 Artificial Intelligence Through the Eyes of the Public An Interactive Qualifying Project Report submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by ____________________________________ Matthew Dodd ____________________________________ Alexander Grant ____________________________________ Latiff Seruwagi Approved: __________________________________________________ Professor David C Brown, Major Advisor Abstract: Artificial Intelligence is becoming a popular field in computer science. In this report we explored its history, major accomplishments and the visions of its creators. We looked at how Artificial Intelligence experts influence reporting and engineered a survey to gauge public opinion. We also examined expert predictions concerning the future of the field as well as media coverage of its recent accomplishments. These results were then used to explore the links between expert opinion, public opinion and media coverage. ii Authorship Abstract Seruwagi 1. Introduction Seruwagi 1.1. Subject Seruwagi 1.2. Goals Seruwagi 1.3. Motivation Seruwagi 1.4. Possible Outcomes Seruwagi 2. Review of Related Work Seruwagi 2.1. Past IQP Seruwagi 3. Problem Seruwagi & Grant 3.1. Goals Seruwagi & Grant 3.2. Requirements Seruwagi & Grant 4. Methodology Dodd, Grant & Seruwagi 4.1. Motivation Grant 4.2. Process Dodd, Grant & Seruwagi 4.3. Survey Dodd & Grant 5. Background Seruwagi 5.1. Theoretical and Historical Foundations Seruwagi 5.2. Key Contributors and Ideas Seruwagi 5.3. Approaches to and Subfields of Artificial Intelligence Seruwagi 6. Current Information Dodd & Grant 6.1. Where Artificial Intelligence is Dodd 6.2. Where Artificial Intelligence is Going Grant 7. Results Dodd & Grant 7.1.