The Shrine James Herbert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DESIGN REVIEW COMMITTEE AGENDA DATE: Tuesday, June 22, 2021 TIME: 1:00 P.M

DESIGN REVIEW COMMITTEE AGENDA DATE: Tuesday, June 22, 2021 TIME: 1:00 P.M. Eastern Time PLACE: Carl T. Langford Boardroom One Jeff Fuqua Boulevard, Orlando International Airport The Greater Orlando Aviation Authority will adhere to any guidelines or executive orders as established by local, state, or the federal government in which virtual meetings are permitted during certain circumstances. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines, and the Greater Orlando Aviation Authority’s ongoing focus on safety regarding events and meetings, seating at sunshine committee meetings will be limited according to space and social distancing. Attendance is on a first-come, first-served basis. The Aviation Authority is subject to federal mask mandates. Federal law requires wearing a mask at all times in and on the airport property. Failure to comply may result in removal and denial of re-entry. Refusing to wear a mask in or on the airport property is a violation of federal law; individuals may be subject to penalties under federal law. RECORDING SECRETARY PHONE NUMBER EMAIL ADDRESS Tara Ciaglia 407-825-4461 [email protected] ITEM 1 CONSIDERATION OF Barnie's Coffee & Tea T-S1388 in South Terminal C S. Smith CONSIDERATION OF Provisions by Cask & Larder and Cask & Larder Bar and ITEM 2 S. Smith Bits T-S1390 in South Terminal C ITEM 3 CONSIDERATION OF Wine Bar George T-S1391 in South Terminal C S. Smith ITEM 4 CONSIDERATION OF Sunshine Diner T-S1392 in South Terminal C S. Smith ITEM 5 CONSIDERATION OF Orlando Brewing Bar & Bites T-S1393 in South Terminal C S. -

Beyond Reach

Beyond Reach By Robert Denton III At least the tea was good. A minor point in the Kaiu lands’ favor, but at this point Asako Tsuki would accept any comfort she could find. The weeks of travel had been one trial after the next. The sprawling tea farms and marshy rice paddies of the Quiet Wind Plain had been an oasis among the dingy, unwelcoming Crab provinces. Her assignment, while lacking prestige, could raise Tsuki’s position in the clan. But truth be told, she didn’t want to be here. The tether to her heart was being pulled, far north to her cozy little nook in the Meiyoko District library, a small desk littered with melted wax, a window overlooking the Bay of the Golden Sun, and a scroll containing the ninth-century biography of the folk hero Shiba Katsue, whose precious text faded a little more each day, begging for transcription onto paper that wasn’t deteriorating. I should be there, not here, she thought, trying not to imagine how many such transcriptions would greet her when she finally returned. It could be days before she caught up. The woman before her cleared her throat, and Tsuki brought herself back to her present surroundings: an austere room in a Kaiu tower in a small keep whose name she’d already forgotten. “I regret that I cannot approve your request,” Kaiu Hitsuko said. She was a stark-looking woman with brown eyes and faint sideburns, and a smile that never touched her eyes. “Even if we knew the Kuni daimyō’s current location, travel through the southern provinces has been restricted lately. -

FEVER 1793 VOCABULARY Bates Cajoling to Diminish Or Make Less Strong Persuading by Using Flattery Or Promises

FEVER 1793 VOCABULARY bates cajoling to diminish or make less strong persuading by using flattery or promises abhorred canteen hated; despised portable drinking flask addle-patted conceded dull-witted; stupid To acknowledge, often reluctantly, as being true, just, or proper; admit agile quick, nimble condolences expressions of sympathy almshouse a home for the poor, supported by charity or contracted (will be on quiz) public funds. to catch or develop an illness or disease anguish cherub Extreme mental distress a depiction of an angel apothecary delectable one who prepares and sells drugs for pleasing to the senses, especially to the medicinal purposes sense of taste; delicious arduous demure hard to do, requiring much effort quiet and modest; reserved baffled despair puzzled, confused the feeling that everything is wrong and nothing will turn out well bilious suffering from or suggesting a liver disorder destitute (will be on quiz) or gastric distress extremely poor; lacking necessities like food and shelter brandish (v.) to wave or flourish in a menacing or vigorous fashion devoured greedily eaten/consumed FEVER 1793 VOCABULARY discreetly without drawing attention gala a public entertainment marking a special event, a festive occasion; festive, showy dollop a blob or small amount of something gaunt very thin especially from disease or hunger dote or cold shower with love grippe dowry influenza; the flu money or property brought by a woman to her husband at marriage gumption courage and initiative; common sense droll comical in an odd -

Larder Beetle

Pest Control Information Sheet Larder Beetle Larder beetles are occasional pests of households where they feed on a wide variety of animal protein-based products. Common foods for these beetles include leather goods, hides, skins, dried fish, pet food, bacon, cheese and feathers. The adult beetles fly well and may be seen around the house, but infestations normally start either in kitchens where food scraps have built up, in birds’ nests or occasionally under floors where a rat or mouse has died. They rarely cause much damage in the home Appearance Adults (above) are 7-10 mm long, dark brown to black, with a lighter stripe across the back. The larvae (below) are worm-like, fairly hairy, dark brown in colour, and appear banded. They are 10-14 mm in length. Signs of Infestation Often the first indication of an infestation is finding the moulted skins of the larvae. However, sightings of several adults can also point to this. Biology Female beetle lays up to 200 eggs on a food source which hatch within a week. The larvae moult up to 5 or 6 times over a period of 5-8 weeks, the pupate and after 2-4 weeks the adult beetle hatches. The beetles can live up to 6 months. How fast each stage of the lifecycle completes depends on conditions. From egg to adult can be a little as 2 months, or as long as 12 months. Significance Larder beetles are serious pests in domestic kitchens, particularly around food cupboards, cookers (where they are attracted by grease or fat) and refrigerators. -

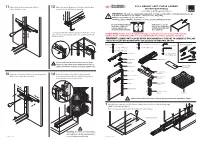

FULL HEIGHT SOFT CLOSE LARDER 11 Adjust Vertical Door Alignment with the 12 Adjust the Vertical Alignment of the Door with the Alen 3 Door Bracket Screws

FULL HEIGHT SOFT CLOSE LARDER 11 Adjust vertical door alignment with the 12 Adjust the vertical alignment of the door with the Alen 3 door bracket screws. screw located under the bottom runner. 300/400/500/600mm Assembly and fitting instructions IMPORTANT - The unit has a maximum loading limit of 100kg. Load should be evenly distributed across all trays with maximum load capacity for each tray not exceeding 16kg. No lubricant should be used on the runners. All fixings supplied MUST be used in the locations specified during installation. Wall For units 400mm wide and Unit must be securely above, two additional Additional fixed to the wall using a cabinet support legs legs suitable fixing bracket G should be fitted centrally. (not supplied). ‘Fine’ adjustment of the vertical alignment of the door can be achieved by compressing the stop cover and sliding towards PLEASE NOTE - Failure to use all supplied fittings according to instructions may void warranty. the front or rear. Handles must be mounted on the door in a central position in order to guarantee operation. WARNING! LARDER UNITS CAN BE HEAVY AND DANGEROUS. FAILURE TO CORRECTLY FOLLOW THESE INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS COULD LEAD TO PERSONAL INJURY. A x6 M6 washer D x6 M6 x 12mm countersunk screw Parts F x1 Alen key 2.5mm Tools required B x30 3.5 x 16mm screw E x3 M5 x 12mm screw G x1 Alen key 4mm C x6 M6 x 12mm screw Top runner x1 H x6 M5 Grub screw T (pre installed in frame) J K Stop spring x1 Bottom runner x1 Now refer back to instruction No. -

Village Level Production and Exchange in an Early State

The Village Larder: Village Level Production and Exchange in an Early State Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Klucas, Eric Eugene, 1957- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 21:26:36 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565574 THE VILLAGE LARDER: VILLAGE LEVEL PRODUCTION AND EXCHANGE IN AN EARLY STATE by Eric Eugene Klueas A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 9 6 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA ® GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Final Examination Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by____ Eric Eugene Klucas______ entitled The Village Larder: Village Level Production and Exchange in an Early State _______ ~__________ ________ and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy__________ Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate's submission of the final copy of the dissertation to the Graduate College, I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement• 9y/7/f6 Dissertation Director Date 7 3 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. -

Furniture Brochure

Furniture Furniture solutions in movement solutions in movement Thomas Regout International B.V. offers a broad range of sliding solutions that help move your application in any direction: horizontal, vertical and diagonal. Our slides can be found in a wide range of applications in many market segments. In our long history we have grown into the company we are today: a major innovative player in automotive and industrial markets, as well as in furniture, professional storage and audio visual segments. We are continuously broadening our product range with new product groups, features and other solutions to fulfil your needs. Furniture In our own R&D department we design innovative sliding systems for different furniture applications. During the years we have gained a lot of experience and for that reason we can provide our customers with an extensive line of special features and telescopic slides with a high quality feeling. Besides Thomas Regout’s outstanding design capabilities for the wide range of products in the furniture markets, the company is also competent in designing complete customized systems. Our main focus is to be and to remain the best quality partner for our customers in mutual beneficial partnerships; partnerships that add value and power to your and our organization. Office furniture Kitchen furniture Shopfitting Furniture Furniture Ulf HD Titan Larder unit Finn Products Our wide range of sliding systems can be used in a lot of different Finn The Finn is a 2-beam cold rolled drawer slide applicable furniture applications. Our main products in this program are the for medium duty applications such as kitchen and bathroom Ulf HD, the Titan, Larder unit and the Finn slide. -

The Inner Shrine a Novel of Today

1 THE INNER SHRINE A NOVEL OF TODAY HARPER & BROTHERS NEW YORK AND LONDON M.C.M.I.X Copyright, 1908, 1909, by HARPER & BROTHERS. All rights reserved. Published May, 1909. I Though she had counted the strokes of every hour since midnight, Mrs. Eveleth had no thought of going to bed. When she was not sitting bolt upright, indifferent to comfort, in one of the stiff-backed, gilded chairs, she was limping, with the aid of her cane, up and down the long suite of salons, listening for the sound of wheels. She knew that George and Diane would be surprised to find her waiting up for them, and that they might even be annoyed; but in her state of dread it was impossible to yield to small considerations. She could hardly tell how this presentiment of disaster had taken hold upon her, for the beginning of it must have come as imperceptibly as the first flicker of dusk across the radiance of an afternoon. Looking back, she could almost make herself believe that she had seen its shadow over her early satisfaction in her son's marriage to Diane. Certainly she had felt it there before their honeymoon was over. The four years that had passed since then had been spent—or, at least, she would have said so now—in waiting for the peril to present itself. And yet, had she been called on to explain why she saw it stalking through the darkness of this particular June night, she would have found it difficult to give coherent statement to her fear. -

Children's Literature Bibliographies

appendix C Children’s Literature Bibliographies Developed in consultation with more than a dozen experts, this bibliography is struc- tured to help you find and enjoy quality literature, and to help you spend more time read- ing children’s books than a textbook. It is also structured to help meet the needs of elementary teachers. The criteria used for selection are • Because it is underused, an emphasis on multicultural and international literature • Because they are underrepresented, an emphasis on the work of “cultural insiders” and authors and illustrators of color • High literary quality and high visual quality for picture books • Appeal to a dual audience of adults and children • A blend of the old and the new • Curricular usefulness to practicing teachers • Suitable choices for permanent classroom libraries Many of the books are award winners. To help you find books for ELLs, I have placed a plus sign (+) if the book is writ- ten in both English and another language. To help you find multicultural authors and il- lustrators, I have placed an asterick (*) to indicate that the author and/or illustrator is a member of underrepresented groups. They are also often cultural insiders. I identify the ethnicity of the authors only if they are is clearly identified in the book. Appendix D in Encountering Children’s Literature: An Arts Approach by Jane Gangi (2004) has a com- plete list of international and multicultural authors who correspond with the astericks. Some writers and illustrators of color want to be known as good writers and good illustrators, not as good “Latino” or “Japanese American” writers and/or illustrators. -

Children's Books & Illustrated

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 105 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #423 - Harry Neilson original watercolor “Mince Pies” #260 - Box for 19th century train game #416 - Nazi Biography of Hitler for children #568 - signed by Mark Twain #509 - Rare Russian propoganda #371 - Norman Lindsay’s Magic Pudding 1st edition in dust wrapper #372 - German Little Red Riding Hood Helen & Marc Younger Pg 3 [email protected] STRIKING ABC MANUSCRIPT FOLIO 1. ABC.ABC MANUSCRIPT by Helen Belkin. No date, circa 1930. This is an amazing original ABC manuscript presented on 27 large pieces of artist board (one for each letter plus a dedication page). -

The Festivalisation of Pacific Cultures in New Zealand: Diasporic Flow and Identity Within ‘A Sea of Islands’

The Festivalisation of Pacific Cultures in New Zealand: Diasporic Flow and Identity within ‘a Sea of Islands’ A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Otago Dunedin New Zealand Jared Mackley-Crump 2012 Abstract In the second half of the twentieth century, New Zealand witnessed a period of significant change, a period that resulted in dramatic demographic shifts. As a result of economic diversification, the New Zealand government looked to the Pacific (and to the at the time predominantly rural Māori population) to fill increasing labour shortages. Pacific Peoples began to migrate to New Zealand in large numbers from the mid-1960s and continued to do so until the mid-1970s, by which time changing economic conditions had impacted the country’s migration needs. At around this time, in 1976, the first major moment of the festivalisation of Pacific cultures occured. As the communities continued to grow and become entrenched, more festivals were initiated across the country. By 2010, with Pacific peoples making up approximately 7% of the population, there were twenty-five annual festivals held from the northernmost towns to the bottom of the South Island. By comparing the history of Pacific festivals and peoples in New Zealand, I argue that festivals reflect how Pacific communities have been transformed from small communities of migrants to large communities of largely New Zealand-born Pacific peoples. Uncovering the meanings of festivals and the musical performances presented within festival spaces, I show how notions of place, culture and identity have been changed in the process. Conceiving of the Pacific as a vast interconnected ‘Sea of Islands’ kinship network (Hau’ofa 1994), where people, trade, arts and customs have circulated across millennia, I propose that Pacific festivals represent the most highly visible public manifestations of this network operating within New Zealand, and of New Zealand’s place within it. -

The Hotel Brighton

THE HOTEL main lobby, and an attached night-club, Bar Rogue, will be used as both a convention suite and as a venue for sponsored parties. SITUATED NEAR THE MARINA on Old For those who want more luxurious accom- Steine Road, the Royal Albion Hotel stands modation or are attending on a limited budget, directly opposite Brighton’s iconic Palace Pier there are plenty of alternatives in the immediate with its bright arcades, funfair and ghost train, surrounding. and overlooking the English Channel. It offers These range from luxury boutique hotels like economical accommodation in architectural The Grand, The Metropole and the Hotel du surroundings that are redolent of the Regency Vin, to simple Bed & Breakfast services. The and Edwardian eras. Thistle, Holiday Inn and the Radisson Blu GUESTS OF HONOUR The World Horror Convention has put a Hotel hotels are only a few minutes’ walk away. block on most of the 185 rooms in this historic and ideally-situated hotel. The £79 per night TANITH LEE, DAVID CASE room rate per night includes a buffet breakfast BRIGHTON and all taxes. Author Guests of Honour There is an on-site dining room, Jenny’s BRIGHTON IS FILLED with restaurants, wine Restaurant, which serves traditional English bars and pubs catering for every taste and budg- LES EDWARDS, DAVE CARSON dishes, while the modern Pavilion Bar features et, so there is no problem eating out every night: views of Brighton’s Victorian Promenade and a selection of a few great restaurants is available Artist Guests of Honour offers light snacks and a wide selection of drinks on the convention website.