2014 REPORT to CONGRESS of the U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC and SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Primer on Governance Issues for China and Hong Kong

A Primer on Governance Issues for China and Hong Kong Michael DeGolyer October 2010 marks the 40th anniversary of the establishment of Canadian diplomatic relations with China. In recent years we usually think of China in terms of trade or currency issues or the potential impact of the booming Chinese economy. The political system is ignored as it is thought to be outside the western democratic tradition. This article looks at how modern China is dealing 2010 CanLIIDocs 256 with political forces arising from its increasingly capitalist economic system. It explains the very strong resistance to federalist theory although in some ways China seems headed toward a kind of de facto federalism. It suggests, particularly in the context of China-Hong Kong relations, we may be witnessing a new approach to governance which deserves to be better known among western states as they grapple with their own governance issues and as they try to come to terms with the emergence of China as a world power. entral authorities of the Peoples Republic Despite official denials that China practices any form of China are sensitive to even discussing of federalism, non-China based scholars such as Zheng Cfederalism. Those within China advocating Yongnian1 of the National University of Singapore federalism as a solution to China’s complex ethnic and may and do make the case for federalism in China. He regional relations have more than once run afoul of argues that in truth China governs itself behaviorally official suspicion that federalism is another name for as a de facto federalist state. -

Governance and Remuneration 2014

Governance & remuneration reportStrategic In this section Our Board 72 Our Corporate Executive Team 76 Chairman’s letter 78 Corporate governance framework 79 Board report to shareholders Oversight and stewardship in 2014 and future actions 80 remuneration & Governance Leadership and effectiveness 82 Committee reports Audit & Risk 86 Nominations 92 Corporate Responsibility 94 Remuneration report Chairman’s annual statement 96 Annual report on remuneration 97 2014 Remuneration policy report 119 Financial statements Financial Investor information Investor GSK Annual Report 2014 71 Our Board Strategic reportStrategic Diversity Experience International experience Composition Tenure (Non-Executives) % % % % Scientific 19 Global 75 Executive 19 Up to 3 years 39 % % % % Finance 31 USA 100 Non-Executive 81 3-6 years 15 % % % % Industry 50 Europe 94 Male 69 7-9 years 23 % % % EMAP 63 Female 31 Over 9 years 23 Sir Christopher Gent 66 Skills and experience Chairman Sir Christopher has many years of experience of leading global businesses and a track record of delivering outstanding performance Governance & remuneration & Governance Nationality in highly competitive industries. He was appointed Managing Director British of Vodafone plc in 1985 and then became its Chief Executive Officer Appointment date in 1997 until his retirement in 2003. Sir Christopher was also a 1 June 2004 and as Chairman Non-Executive Director of Ferrari SpA and a member of the British on 1 January 2005 Airways International Business Advisory Board. Committee membership External appointments Corporate Responsibility Sir Christopher is a Senior Adviser at Bain & Co. Committee Chairman, Nominations, Remuneration and Finance Sir Philip Hampton 61 Skills and experience Chairman Designate Prior to joining GSK, Sir Philip chaired major FTSE 100 companies including J Sainsbury plc. -

Doug Ogden December 2006

JPMorgan’s Hands-On China Series Views you can use Transcript – Doug Ogden December 2006 NEW REPORT Investment Opportunities in China’s Clean Energy Technology In this presentation to global investors, Douglas Ogden, Director of the China Sustainable Energy Program in Beijing and Executive Vice President of The Energy Foundation in San Francisco, discussed the numerous opportunities for clean energy technology investment in China. These opportunities depend on social investment in upstream policies that shape markets conducive to modern, clean energy technologies. China’s traditional energy technologies, based predominantly on oil and relatively dirty coal, are priced well below social costs, skewing China’s market in favor of inefficient, Doug Ogden outmoded, and heavily polluting energy technologies. The current unsustainable situation has enormous public health and environmental costs. Director, China Sustainable These conditions, however, are being gradually reversed through concerted public policy Energy Program and legal institutional capacity building supported by international non-profits, multilateral Executive Vice President, banks, and the business community. Energy Foundation Engagement in policy development and implementation can be a highly successful strategy for creating market opportunities for clean energy technologies: Witness the progress over the last 8 years that have ushered in: China’s advanced fuel economy standards—driving markets in advanced engine technologies; The national renewable energy law and wind concessions—creating -

Health Privatisation in China: from the Perspective of Subnational

Health Privatisation in China: from the Perspective of Subnational Governments By FENG Qian Submitted to Central European University Department of Political Science In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science CEU eTD Collection Supervisor: Anil Duman Budapest, Hungary 2020 Abstract From 2009, the Chinese government started to promote the policy She Hui Ban Yi/SHBY that encourages private investment in hospitals. This strategy of promoting private investment in hospitals represents the overall privatisation trend in Chinese health policymaking. Building on the national level health policymaking, the thesis focuses on the subnational governments in China and explains why are this national initiative has been implemented differently at the subnational level. Most existing studies in this topic focus either on the national level policymaking, discussing the relations between welfare policies and regime type or ideologies; or on the efficiency of public versus private hospitals in health sector by evaluating the outcomes. The thesis aims to understand SHBY and privatisation in health mainly from the local governments’ perspective, analysing how the fiscal survival pressure and political incentives affect the actual health policymaking in local governments in China. Drawing on official statistics, government policies and existing studies, the thesis mainly consider two types of influencing factors, and categorises three types of responses at the subnational levels. While the implementation of this policy requires a lot of resources and efforts, the thesis emphasises that, firstly, for the local governments, the fiscal impact, especially the hard budget constraint from the central government and soft budget constraint to the local public sector, plays the key role in health privatisation policies in China. -

Fiscal Federalism in Chinese Taxation Wei Cui Allard School of Law at the University of British Columbia, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Allard Research Commons (Peter A. Allard School of Law) The Peter A. Allard School of Law Allard Research Commons Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2011 Fiscal Federalism in Chinese Taxation Wei Cui Allard School of Law at the University of British Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.allard.ubc.ca/fac_pubs Part of the Tax Law Commons Citation Details Wei Cui, "Fiscal Federalism in Chinese Taxation" (2011) 3 World Tax J 455. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Allard Research Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Allard Research Commons. Wei Cui* Fiscal Federalism in Chinese Taxation1 The recent policy literature on fiscal federalism in China has concentrated on the large “vertical fiscal gap” resulting in inadequate local provision of public goods and services. Thus there is an evident interest in giving local governments more taxing powers. After a brief historical survey, the article discusses a 1993 State Council directive that centralized taxing power. This has led local governments to make use of their control over tax administration to alter effective tax rates, and to the practice of “refund after collection”, whereby local governments disguise tax cuts as expenditures, following a logic opposite to tax expenditures. This study concludes, firstly, that the allocation of taxing power is still done outside the framework of the law, and secondly, that the government has not been able to settle on a stable allocation. -

Global Events

GLOBAL EVENTS Education • Professional Leverage • Networking • Philanthropy Industry Icons Sep 18, 2013 New York: A Conversation With Adena T. Friedman, Chief Financial Officer, The Carlyle Group Adena Friedman, Chief Financial Officer, The Carlyle Group Bill Stone, Founder and CEO, Moderator, SS&C Technologies Jun 3, 2013 Washington: Conversation with David M. Rubenstein, Co-Founder, The Carlyle Group David M. Rubenstein, Co-Founder, The Carlyle Group Jeffrey R. Houle, Moderator, Partner, DLA Piper Apr 3, 2013 New York: Fireside Chat with Saba Capital's Boaz Weinstein Boaz Weinstein, Founder & CIO, Saba Capital Stephanie Ruhle, Moderator, Anchor, Bloomberg Oct 30, 2012 Newport Beach: A Conversation with Dr. Mohamed El-Erian of PIMCO: Investing in a Zero-Interest Rate Environment Dr. Mohamed El-Erian, Chief Executive Officer and Co-CIO, PIMCO Lupin Rahman, Moderator, Executive Vice President, PIMCO Marc Seidner, Managing Director and Generalist Portfolio Manager, PIMCO Qi Wang, Managing Director and Portfolio Manager, PIMCO Oct 16, 2012 New York: Know Yourself and Your Decision-Making Process: A Conversation with Nobel Laureate Dr. Daniel Kahneman Dr. Daniel Kahneman, Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology and Professor of Public Affairs Emeritus, Princeton University Jason Zweig, Moderator, Columnist, Wall Street Journal Sep 19, 2012 New York: Conversation with Eric E. Schmidt, Executive Chairman of Google Eric E. Schmidt, Executive Chairman, Google Apr 30, 2012 New York: An Armchair Discussion with John J. Mack on Leadership John J. Mack, former Chairman and CEO, Morgan Stanley Joanne Pace, Moderator, former Chief Operating Officer, Morgan Stanley Investment Management Jan 25, 2012 Geneva: Philippe Jabre Talks Markets Philippe Jabre, Chief Investment Officer, Jabre Capital Partners Dec 8, 2011 Los Angeles: Dinner Event with Howard Marks, Chairman, Oaktree Capital Oct 26, 2011 Los Angeles: Renee Haugerud, Founder, CIO & Managing Principal, Galtere, Ltd. -

The Effects of Forest Area Changes on Extreme Temperature Indexes Between the 1900S and 2010S in Heilongjiang Province, China

remote sensing Article The Effects of Forest Area Changes on Extreme Temperature Indexes between the 1900s and 2010s in Heilongjiang Province, China Lijuan Zhang 1,*, Tao Pan 1, Hongwen Zhang 2, Xiaxiang Li 1 ID and Lanqi Jiang 3,4,5 1 Key Laboratory of Remote Sensing Monitoring of Geographic Environment, Harbin Normal University, Harbin 150025, China; [email protected] (T.P.); [email protected] (X.L.) 2 Key Laboratory of Land Surface Process and Climate Change in Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou 730000, China; [email protected] 3 Innovation and Opening Laboratory of Regional Eco-Meteorology in Northeast, China Meteorological Administration, Harbin 150030, China; [email protected] 4 Meteorological Academician Workstation of Heilongjiang Province, Harbin 150030, China 5 Heilongjiang Province Institute of Meteorological Sciences, Harbin 150030, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 October 2017; Accepted: 6 December 2017; Published: 9 December 2017 Abstract: Land use and land cover changes (LUCC) are thought to be amongst the most important impacts exerted by humans on climate. However, relatively little research has been carried out so far on the effects of LUCC on extreme climate change other than on regional temperatures and precipitation. In this paper, we apply a regional weather research and forecasting (WRF) climate model using LUCC data from Heilongjiang Province, that was collected between the 1900s and 2010s, to explore how changes in forest cover influence extreme temperature indexes. Our selection of extreme high, low, and daily temperature indexes for analysis in this study enables the calculation of a five-year numerical integration trail with changing forest space. -

Download Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS AN NUAL RE PORT JULY 1, 2003-JUNE 30, 2004 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, NW 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 434-9800 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www.cfr.org E-mail [email protected] OFFICERS and DIRECTORS 2004-2005 OFFICERS DIRECTORS Term Expiring 2009 Peter G. Peterson* Term Expiring 2005 Madeleine K. Albright Chairman of the Board Jessica P Einhorn Richard N. Fostert Carla A. Hills* Louis V Gerstner Jr. Maurice R. Greenbergt Vice Chairman Carla A. Hills*t Robert E. Rubin George J. Mitchell Vice Chairman Robert E. Rubin Joseph S. Nye Jr. Richard N. Haass Warren B. Rudman Fareed Zakaria President Andrew Young Michael R Peters Richard N. Haass ex officio Executive Vice President Term Expiring 2006 Janice L. Murray Jeffrey L. Bewkes Senior Vice President OFFICERS AND and Treasurer Henry S. Bienen DIRECTORS, EMERITUS David Kellogg Lee Cullum AND HONORARY Senior Vice President, Corporate Richard C. Holbrooke Leslie H. Gelb Affairs, and Publisher Joan E. Spero President Emeritus Irina A. Faskianos Vice President, Vin Weber Maurice R. Greenberg Honorary Vice Chairman National Program and Academic Outreach Term Expiring 2007 Charles McC. Mathias Jr. Elise Carlson Lewis Fouad Ajami Director Emeritus Vice President, Membership David Rockefeller Kenneth M. Duberstein and Fellowship Affairs Honorary Chairman Ronald L. Olson James M. Lindsay Robert A. Scalapino Vice President, Director of Peter G. Peterson* t Director Emeritus Studies, Maurice R. Creenberg Chair Lhomas R. -

Palaeontology and Biostratigraphy of the Lower Cretaceous Qihulin

Dissertation Submitted to the Combined Faculties for the Natural Sciences and for Mathematics of the Ruperto-Carola University of Heidelberg, Germany for the degree of Doctor of Natural Sciences presented by Master of Science: Gang Li Born in: Heilongjiang, China Oral examination: 30 November 2001 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung des Deutschen Akademischen Austauschdienstes (Printed with the support of German Academic Exchange Service) Palaeontology and biostratigraphy of the Lower Cretaceous Qihulin Formation in eastern Heilongjiang, northeastern China Referees: Prof. Dr. Peter Bengtson Prof. Pei-ji Chen This manuscript is produced only for examination as a doctoral dissertation and is not intended as a permanent scientific record. It is therefore not a publication in the sense of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. Abstract The purpose of the study was to provide conclusive evidence for a chronostratigraphical assignment of the Qihulin Formation of the Longzhaogou Group exposed in Mishan and Hulin counties of eastern Heilongjiang, northeastern China. To develop an integrated view of the formation, all collected fossil groups, i.e. the macrofossils (ammonites and bivalves) and microfossils (agglutinated foraminifers and radiolarians) have been studied. The low-diversity ammonite fauna consists of Pseudohaploceras Hyatt, 1900, and Eogaudryceras Spath, 1927, which indicate a Barremian–Aptian age. The bivalve fauna consists of eight genera and 16 species. The occurrence of Thracia rotundata (J. de C: Sowerby) suggests an Aptian age. The agglutinated foraminifers comprise ten genera and 16 species, including common Lower Cretaceous species such as Ammodiscus rotalarius Loeblich & Tappan, 1949, Cribrostomoides? nonioninoides (Reuss, 1836), Haplophragmoides concavus (Chapman, 1892), Trochommina depressa Lozo, 1944. The radiolarians comprise ten genera and 17 species, where Novixitus sp., Xitus cf. -

DRAINAGE BASINS of the SEA of OKHOTSK and SEA of JAPAN Chapter 2

60 DRAINAGE BASINS OF THE SEA OF OKHOTSK AND SEA OF JAPAN Chapter 2 SEA OF OKHOTSK AND SEA OF JAPAN 61 62 AMUR RIVER BASIN 66 LAKE XINGKAI/KHANKA 66 TUMEN RIVER BASIN Chapter 2 62 SEA OF OKHOTSK AND SEA OF JAPAN This chapter deals with major transboundary rivers discharging into the Sea of Okhotsk and the Sea of Japan and their major transboundary tributaries. It also includes lakes located within the basins of these seas. TRANSBOUNDARY WATERS IN THE BASINS OF THE SEA OF OKHOTSK AND THE SEA OF JAPAN1 Basin/sub-basin(s) Total area (km2) Recipient Riparian countries Lakes in the basin Amur 1,855,000 Sea of Okhotsk CN, MN, RU … - Argun 164,000 Amur CN, RU … - Ussuri 193,000 Amur CN, RU Lake Khanka Sujfun 18,300 Sea of Japan CN, RU … Tumen 33,800 Sea of Japan CN, KP, RU … 1 The assessment of water bodies in italics was not included in the present publication. 1 AMUR RIVER BASIN o 55 110o 120o 130o 140o SEA OF Zeya OKHOTSK R U S S I A N Reservoir F E mur D un A E mg Z A e R Ulan Ude Chita y ilka a A a Sh r od T u Ing m n A u I Onon g ya r re A Bu O n e N N Khabarovsk Ulaanbaatar Qiqihar i MONGOLIA a r u u gh s n s o U CHIN A S Lake Khanka N Harbin 45o Sapporo A Suj fu Jilin n Changchun SEA O F P n e JA PA N m Vladivostok A Tu Kilometres Shenyang 0 200 400 600 The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map Ch’ongjin J do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

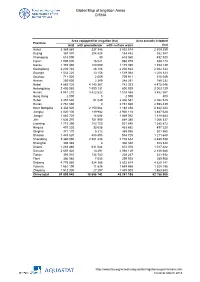

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

2005 REPORT to CONGRESS of the U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC and SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION

2005 REPORT TO CONGRESS of the U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 2005 Printed for the use of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.uscc.gov 1 2005 REPORT TO CONGRESS of the U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 2005 Printed for the use of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.uscc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2005 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION Hall of the States, Suite 602 444 North Capitol Street, NW Washington, DC 20001 Phone: (202) 624–1407 Fax: (202) 624–1406 E-mail: [email protected] www.uscc.gov COMMISSIONERS Hon. C. RICHARD D’AMATO, Chairman ROGER W. ROBINSON, Jr., Vice Chairman CAROLYN BARTHOLOMEW, Commissioner Hon. PATRICK A. MULLOY, Commissioner GEORGE BECKER, Commissioner Hon. WILLIAM A. REINSCH, Commissioner STEPHEN D. BRYEN, Commissioner Hon. FRED D. THOMPSON, Commissioner THOMAS DONNELLY, Commissioner MICHAEL R. WESSEL, Commissioner JUNE TEUFEL DREYER, Commissioner LARRY M. WORTZEL, Commissioner T. SCOTT BUNTON, Executive Director KATHLEEN J. MICHELS, Associate Director The Commission was created in October 2000 by the Floyd D. Spence Na- tional Defense Authorization Act for 2001 sec. 1238, Public Law 106– 398, 114 STAT.