Asian Americans in Hip Hop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BAM Presents the New York Premiere of Rules of the Game, by Jonah Bokaer, Daniel Arsham, and Pharrell Williams, As Part of a Triple Bill—Nov 10–12

BAM presents the New York premiere of Rules Of The Game, by Jonah Bokaer, Daniel Arsham, and Pharrell Williams, as part of a triple bill—Nov 10–12 Bloomberg Philanthropies is the Season Sponsor Rules Of The Game Jonah Bokaer and Daniel Arsham With an original score by Pharrell Williams Arranged and co-composed by David Campbell BAM Howard Gilman Opera House (30 Lafayette Ave) Nov 10–12 at 7:30pm Tickets start at $25 RECESS (2010) Choreography and performance by Jonah Bokaer Scenography by Daniel Arsham Music by Stavros Gasparatos Lighting design by Aaron Copp Costumes by Richard Chai Why Patterns (2011) Choreography and direction by Jonah Bokaer Scenography by Snarkitecture (Daniel Arsham and Alex Mustonen) Music by Morton Feldman and Alexis Georgopoulos/ARP Lighting design by Aaron Copp Costumes by Richard Chai Rules Of The Game (2016) Choreography and direction by Jonah Bokaer Scenography by Daniel Arsham Original score by Pharrell Williams Arranged and conducted by David Campbell Exclusive recording by the Dallas Symphony Orchestra Lighting design by Aaron Copp Costumes by Chris Stamp/STAMPD Talk: Dance as Visual Art With Jonah Bokaer in conversation with Jenny Schlenzka, Associate Curator at MoMA PS1 Nov 11 at 6pm BAM Fisher Hillman Studio Tickets: $25 ($12.50 for BAM Members) Master Class: Jonah Bokaer Co-presented by BAM and Mark Morris Dance Group Nov 5 at 4:30pm, Mark Morris Dance Center (3 Lafayette Ave) Price: $30 For dancers of all levels Visit BAM.org/master-classes for more information and to register Oct 11, 2016/Brooklyn, NY—Rules Of The Game—the centerpiece of a triple bill of New York City premieres—is a new multidisciplinary work created by choreographer Jonah Bokaer, visual artist Daniel Arsham, and composer Pharrell Williams. -

Chinatown and Urban Redevelopment: a Spatial Narrative of Race, Identity, and Urban Politics 1950 – 2000

CHINATOWN AND URBAN REDEVELOPMENT: A SPATIAL NARRATIVE OF RACE, IDENTITY, AND URBAN POLITICS 1950 – 2000 BY CHUO LI DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Landscape Architecture in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2011 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor D. Fairchild Ruggles, Chair Professor Dianne Harris Associate Professor Martin Manalansan Associate Professor Faranak Miraftab Abstract The dissertation explores the intricate relations between landscape, race/ethnicity, and urban economy and politics in American Chinatowns. It focuses on the landscape changes and spatial struggles in the Chinatowns under the forces of urban redevelopment after WWII. As the world has entered into a global era in the second half of the twentieth century, the conditions of Chinatown have significantly changed due to the explosion of information and the blurring of racial and cultural boundaries. One major change has been the new agenda of urban land planning which increasingly prioritizes the rationality of capital accumulation. The different stages of urban redevelopment have in common the deliberate efforts to manipulate the land uses and spatial representations of Chinatown as part of the socio-cultural strategies of urban development. A central thread linking the dissertation’s chapters is the attempt to examine the contingent and often contradictory production and reproduction of socio-spatial forms in Chinatowns when the world is increasingly structured around the dynamics of economic and technological changes with the new forms of global and local activities. Late capitalism has dramatically altered city forms such that a new understanding of the role of ethnicity and race in the making of urban space is required. -

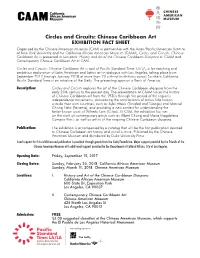

Circles and Circuits: Chinese Caribbean

Circles and Circuits: Chinese Caribbean Art EXHIBITION FACT SHEET Organized by the Chinese American Museum (CAM) in partnership with the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at New York University and the California African American Museum (CAAM), Circles and Circuits: Chinese Caribbean Art is presented in two parts: History and Art of the Chinese Caribbean Diaspora at CAAM and Contemporary Chinese Caribbean Art at CAM. Circles and Circuits: Chinese Caribbean Art is part of Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, a far-reaching and ambitious exploration of Latin American and Latino art in dialogue with Los Angeles, taking place from September 2017 through January 2018 at more than 70 cultural institutions across Southern California. Pacific Standard Time is an initiative of the Getty. The presenting sponsor is Bank of America. Description: Circles and Circuits explores the art of the Chinese Caribbean diaspora from the early 20th century to the present day. The presentation at CAAM traces the history of Chinese Caribbean art from the 1930s through the period of the region’s independence movements, showcasing the contributions of artists little known outside their own countries, such as Sybil Atteck (Trinidad and Tobago) and Manuel Chong Neto (Panama), and providing a new context for understanding the better-known work of Wifredo Lam (Cuba). At CAM, the exhibition focuses on the work of contemporary artists such as Albert Chong and Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons, as well as artists of the ongoing Chinese Caribbean diaspora. Publication: The exhibition is accompanied by a catalog that will be the first publication devoted to Chinese Caribbean art history and visual culture. -

ARTIST INDEX(Continued)

ChartARTIST Codes: CJ (Contemporary Jazz) INDEXINT (Internet) RBC (R&B/Hip-Hop Catalog) –SINGLES– DC (Dance Club Songs) LR (Latin Rhythm) RP (Rap Airplay) –ALBUMS– CL (Traditional Classical) JZ (Traditional Jazz) RBL (R&B Albums) A40 (Adult Top 40) DES (Dance/Electronic Songs) MO (Alternative) RS (Rap Songs) B200 (The Billboard 200) CX (Classical Crossover) LA (Latin Albums) RE (Reggae) AC (Adult Contemporary) H100 (Hot 100) ODS (On-Demand Songs) STS (Streaming Songs) BG (Bluegrass) EA (Dance/Electronic) LPA (Latin Pop Albums) RLP (Rap Albums) ARB (Adult R&B) HA (Hot 100 Airplay) RB (R&B Songs) TSS (Tropical Songs) BL (Blues) GA (Gospel) LRS (Latin Rhythm Albums) RMA (Regional Mexican Albums) CA (Christian AC) HD (Hot Digital Songs) RBH (R&B Hip-Hop) XAS (Holiday Airplay) MAR CA (Country) HOL (Holiday) NA (New Age) TSA (Tropical Albums) CS (Country) HSS (Hot 100 Singles Sales) RKA (Rock Airplay) XMS (Holiday Songs) CC (Christian) HS (Heatseekers) PCA (Catalog) WM (World) CST (Christian Songs) LPS (Latin Pop Songs) RMS (Regional Mexican Songs) 20 CCA (Country Catalog) IND (Independent) RBA (R&B/Hip-Hop) DA (Dance/Mix Show Airplay) LT (Hot Latin Songs) RO (Hot Rock Songs) 2021 $NOT HS 18, 19 BENNY BENASSI DA 16 THE CLARK SISTERS GS 14 EST GEE HS 4; H100 34; ODS 14; RBH 17; RS H.E.R. B200 166; RBL 23; ARB 12, 14; H100 50; -L- 13; STM 13 HA 23; RBH 22; RBS 6, 18 THE 1975 RO 40 GEORGE BENSON CJ 3, 4 CLEAN BANDIT DES 16 LABRINTH STX 20 FAITH EVANS ARB 28 HIKARU UTADA DLP 17 21 SAVAGE B200 63; RBA 36; H100 86; RBH DIERKS BENTLEY CS 21, 24; H100 -

ENG 350 Summer12

ENG 350: THE HISTORY OF HIP-HOP With your host, Dr. Russell A. Potter, a.k.a. Professa RAp Monday - Thursday, 6:30-8:30, Craig-Lee 252 http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ In its rise to the top of the American popular music scene, Hip-hop has taken on all comers, and issued beatdown after beatdown. Yet how many of its fans today know the origins of the music? Sure, people might have heard something of Afrika Bambaataa or Grandmaster Flash, but how about the Last Poets or Grandmaster CAZ? For this class, we’ve booked a ride on the wayback machine which will take us all the way back to Hip-hop’s precursors, including the Blues, Calypso, Ska, and West African griots. From there, we’ll trace its roots and routes through the ‘parties in the park’ in the late 1970’s, the emergence of political Hip-hop with Public Enemy and KRS-One, the turn towards “gangsta” style in the 1990’s, and on into the current pantheon of rappers. Along the way, we’ll take a closer look at the essential elements of Hip-hop culture, including Breaking (breakdancing), Writing (graffiti), and Rapping, with a special look at the past and future of turntablism and digital sampling. Our two required textbook are Bradley and DuBois’s Anthology of Rap (Yale University Press) and Neal and Forman’s That's the Joint: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader are both available at the RIC campus store. Films shown in part or in whole will include Bamboozled, Style Wars, The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, Wild Style, and Zebrahead; there will is also a course blog with a discussion board and a wide array of links to audio and text resources at http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ WRITTEN WORK: An informal response to our readings and listenings is due each week on the blog. -

Obscenity Law and Sexually Explicit Rap Music: Understanding the Effects of Sex, Attitudes, and Beliefs

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/248925838 Obscenity law and sexually explicit rap music: Understanding the effects of sex, attitudes, and beliefs Article in Journal of Applied Communication Research · August 1997 DOI: 10.1080/00909889709365477 CITATIONS READS 27 547 2 authors: Travis Dixon Daniel Linz University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign University of California, Santa Barbara 32 PUBLICATIONS 1,503 CITATIONS 82 PUBLICATIONS 3,612 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Daniel Linz on 28 January 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. !"#$%&'(#)*+%,&$%-.,/*.&-+-%012%34/#5+'$#(1%.6%7&*#6.'/#&8%9&/(&%:&'0&'&; </2%=>%?&/@&'1%=>AA B))+$$%-+(&#*$2%B))+$$%C+(&#*$2%3$@0$)'#D(#./%/@E0+'%FAGFHIJ=>; K@0*#$"+'%L.@(*+-M+ N/6.'E&%O(-%L+M#$(+'+-%#/%P/M*&/-%&/-%Q&*+$%L+M#$(+'+-%R@E0+'2%A>H=FST%L+M#$(+'+-%.66#)+2%U.'(#E+'%V.@$+8%JHW TA%U.'(#E+'%9('++(8%O./-./%QA!%J?V8%4X ?.@'/&*%.6%BDD*#+-%7.EE@/#)&(#./%L+$+&')" K@0*#)&(#./%-+(&#*$8%#/)*@-#/M%#/$('@)(#./$%6.'%&@(".'$%&/-%$@0$)'#D(#./%#/6.'E&(#./2 "((D2YY,,,Z#/6.'E&,.'*-Z).EY$EDDY(#(*+[)./(+/(\(HAJH>JJAI <0$)+/#(1%*&,%&/-%$+]@&**1%+]D*#)#(%'&D%E@$#)2%4/-+'$(&/-#/M%("+%+66+)($ .6%$+]8%&((#(@-+$8%&/-%0+*#+6$ !'&5#$%OZ%C#]./&^%C&/#+*%_Z%O#/`0 &%C.)(.'&*%)&/-#-&(+%&(%("+%4/#5+'$#(1%.6%7&*#6.'/#&8%9&/(&%:&'0&'&%0%K'.6+$$.'%.6%7.EE@/#)&(#./%&/- C#'+)(.'%.6%("+%O&,%&/-%9.)#+(1%K'.M'&E8%4/#5+'$#(1%.6%7&*#6.'/#&8%9&/(&%:&'0&'& !.%)#(+%("#$%B'(#)*+%C#]./8%!'&5#$%OZ%&/-%O#/`8%C&/#+*%_ZaAFFHb%c<0$)+/#(1%*&,%&/-%$+]@&**1%+]D*#)#(%'&D%E@$#)2 4/-+'$(&/-#/M%("+%+66+)($%.6%$+]8%&((#(@-+$8%&/-%0+*#+6$c8%?.@'/&*%.6%BDD*#+-%7.EE@/#)&(#./%L+$+&')"8%=S2%J8%=AH%d%=TA !.%*#/e%(.%("#$%B'(#)*+2%C<N2%A>ZA>G>Y>>F>FGGFH>FJISTHH 4LO2%"((D2YY-]Z-.#Z.'MYA>ZA>G>Y>>F>FGGFH>FJISTHH PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. -

Q&A: Brooklyn Artist Aakash Nihalani Talks Designing Mixtape Covers

Q&A: Brooklyn Artist Aakash Nihalani Talks Designing Mixtape Covers For Das Racist and His New Show, Overlap, Opening at Bose Pacia This Thursday By Zach Baron published: Mon., Nov. 1 2010 @ 12:40PM All images courtesy Bose Pacia The young, Queens-born tape artist Aakash Nihalani did the geometrically stoned cover for Das Racist's Shut Up, Dude mixtape. He's had his distinctive, oddly placed, brightly colored tape installations ripped off by everybody from other street artists to Vampire Weekend. And he's got a new, Jeff Koons-pranking solo show up this Thursday at Dumbo gallery Bose Pacia, entitled Overlap. Das Racist, of course, are playing the afterparty at 17 Frost. In advance of Nihalani's solo debut at the gallery, we chatted a bit about the upcoming show and his brushes with various local musicians, both friendly and otherwise. When last we spoke, I think, it was about whether you'd done the art for Vampire Weekend's "Cousins" video. You hadn't, but you did point me to someone who said "Vampire Weekend totally ripped him off (poorly) without consent or compensation." Did they ever reach out to make it right? Is that video still a sore spot? Nah, they never reached out. I wouldn't be so bummed if they didn't do such a poor imitation. But I kinda can't blame the band as much as the director who 'came up' with the idea for the video. Come to think of it, your aesthetic seems like it's particularly prone to other people borrowing it--is that a source of pain for you? Want to name any other names of people who've ripped you off while we're here? Sometimes it gets weird to see my style copied, but I think it's a benefit to have my stuff be so relatable. -

Introduction Chapter 1

Notes Introduction 1. For The Economistt perpetuating the Patent Office myth, see April 13, 1991, page 83. 2. See Sass. 3. Book publication in 1906. 4.Swirski (2006). 5. For more on eliterary critiques and nobrow artertainment, see Swirski (2005). 6. Carlin, et al., online. 7. Reagan’s first inaugural, January 20, 1981. 8. For background and analysis, see Hess; also excellent study by Lamb. 9. This and following quote in Conason, 78. 10. BBC News, “Obama: Mitt Romney wrong.” 11. NYC cabbies in Bryson and McKay, 24; on regulated economy, Goldin and Libecap; on welfare for Big Business, Schlosser, 72, 102. 12. For an informed critique from the perspective of a Wall Street trader, see Taleb; for a frontal assault on the neoliberal programs of economic austerity and political repression, see Klein; Collins and Yeskel; documentary Walmart. 13. In Kohut, 28. 14. Orwell, 318. 15. Storey, 5; McCabe, 6; Altschull, 424. 16. Kelly, 19. 17. “From falsehood, anything follows.” 18. Calder; also Swirski (2010), Introduction. 19. In The Economist, February 19, 2011: 79. 20. Prominently Gianos; Giglio. 21. The Economistt (2011). 22. For more examples, see Swirski (2010); Tavakoli-Far. My thanks to Alice Tse for her help with the images. Chapter 1 1. In Powers, 137; parts of this research are based on Swirski (2009). 2. Haynes, 19. 168 NOTES 3. In Moyers, 279. 4. Ruderman, 10. 5. In Krassner, 276–77. 6. Green, 57; bottom of paragraph, Ruderman, 179. 7. In Zagorin, 28; next quote 30; Shakespeare did not spare the Trojan War in Troilus and Cressida. -

The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 122–135 Research Article Adam de Paor-Evans* The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0012 Received January 27, 2018; accepted June 2, 2018 Abstract: In the early 1980s, an important facet of hip hop culture developed a style of music known as electro-rap, much of which carries narratives linked to science fiction, fantasy and references to arcade games and comic books. The aim of this article is to build a critical inquiry into the cultural and socio- political presence of these ideas as drivers for the productions of electro-rap, and subsequently through artists from Newcleus to Strange U seeks to interrogate the value of science fiction from the 1980s to the 2000s, evaluating the validity of science fiction’s place in the future of hip hop. Theoretically underpinned by the emerging theories associated with Afrofuturism and Paul Virilio’s dromosphere and picnolepsy concepts, the article reconsiders time and spatial context as a palimpsest whereby the saturation of digitalisation becomes both accelerator and obstacle and proposes a thirdspace-dromology. In conclusion, the article repositions contemporary hip hop and unearths the realities of science fiction and closes by offering specific directions for both the future within and the future of hip hop culture and its potential impact on future society. Keywords: dromosphere, dromology, Afrofuturism, electro-rap, thirdspace, fantasy, Newcleus, Strange U Introduction During the mid-1970s, the language of New York City’s pioneering hip hop practitioners brought them fame amongst their peers, yet the methods of its musical production brought heavy criticism from established musicians. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

Luniz Lunitik Muzik Mp3, Flac, Wma

Luniz Lunitik Muzik mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Lunitik Muzik Released: 1997 Style: Thug Rap, Gangsta, Electro MP3 version RAR size: 1899 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1325 mb WMA version RAR size: 1268 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 731 Other Formats: FLAC AA DXD AU WMA MP4 APE Tracklist Hide Credits Intro 1 1:24 Voice – DJ Thump, Mengesha Highest Niggaz In The Industry 2 4:54 Featuring – B-Legit, E-40 Funkin Over Nuthin' 3 5:33 Featuring – Harm , Too Short In My Nature 4 5:25 Featuring – Eightball & MJG*Producer – Smoke One Productions Jus Mee & U 5 4:54 Co-producer – DJ Quik, G-OneProducer – Raphael Saadiq Game 6 1:17 Voice – T. K. Kirkland 7 My Baby Mamma 4:13 Is It Kool 8 4:35 Vocals – MoKenStef $ad Millionaire 9 4:43 Featuring – Brownstone Killaz On The Payroll 10 6:03 Featuring – Madd Maxx*, Phats Bossilini*, Poppa LQ Phillies 11 4:40 Featuring – Poppa LQ Mobb Sh.. 12 5:13 Featuring – 3X Krazy, Cydal, Swoop G Y Do Thugz Die 13 4:55 Producer – QD IIIVocals – Val Young Hypnotize 14 5:15 Featuring – RedmanProducer – Redman 15 Handcuff Your Hoes 3:21 20 Bluntz A Day (Incl. Hidden Track 11 O ´Clock News) 16 7:36 Featuring – Christion*, The 2 Live Crew Credits Executive-Producer – Chris Hicks , Eric L. Brooks Producer – Bosko (tracks: 8, 11, 12), Mike Dean (tracks: 2, 3, 10, 15, 16), Tone Capone (tracks: 2, 3, 7, 9, 10, 15, 16) Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Noo Trybe Records, 7243 8 44966 2 3, Lunitik Muzik C-Note Records, 7243 8 44966 2 3, Luniz UK 1997 CDVUS 136 (CD, -

Izona S Art: First Album to Be Like a Jackson 5 Thing in the Audience's Eyes That Album (Straight up Pop Without Just Makes the Shows Fun

For the week of Aug. Sept. 10-16 The Lumberjack Happenings A G pseo f Goldfinger Mon. - Thurs. - 5:15, 7:40 H ar kin v Flagstaff I uxurv 11 gets its She’s Sc Lovefy (R) 4650 N. Highway 89 774-4700 (1:30Sat. & Sun. only), 5,7A (9 p.m. Fri. & Sat. only) > I r tyiii The Gamei R) Mon. - Thurs. - 5A 7:30 p.m. hang ups Cl I a-ih. Sat. A Sun. only),!, 2:25,4.5:20, 7,8:10 & (12:40 a.m Fri. & Sal. only). H ercules (G) Flagstaff Mall Cinema out into (10:55 Sat.A Sun. only), 4:20A 9:00 4650 N. Highway 89 52 ^4 5 5 5 Excess Baggage (PG-13) * Jeffrey Bell (10:10 SaL A Sun. only), 1:30,4:30,7:30A 10 Cop L an d (PG-13) Happenings Editor (12:35 a.m. Fri.& Sat. only) (1:45 Sat. - Mon. only), 4:30,7,9:10 & (4:30 p.m. inofifi firm Fri. & Sal. csnly ) the open H oodlum (R) Mon.- Thurs. - 4:45,7p.m. 12:45,3:50,7:20A 10:40 p.m. A ir B ud (R) Four guys from Los AngelesDoubt and the Skeletones G J . Ja n e (R) are ready togive Phoenix the finstopped by to help out. ( 10:30 Sat. A Sun. only), 1:10.4:10, 7:10, 4:45 p.m.A (2:15 Sat.A Sun. only) ger. The Goldfinger "Working with Angelo Moore 10:10 & (i 2:45 a.m.