Univerzita Karlova / Charles University Universidade Do Porto / University of Porto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tribute to Kishore Kumar

Articles by Prince Rama Varma Tribute to Kishore Kumar As a child, I used to listen to a lot of Hindi film songs. As a middle aged man, I still do. The difference however, is that when I was a child I had no idea which song was sung by Mukesh, which song by Rafi, by Kishore and so on unlike these days when I can listen to a Kishore song I have never heard before and roughly pinpoint the year when he may have sung it as well as the actor who may have appeared on screen. On 13th October 1987, I heard that Kishore Kumar had passed away. In the evening there was a tribute to him on TV which was when I discovered that 85% of my favourite songs were sung by him. Like thousands of casual music lovers in our country, I used to be under the delusion that Kishore sang mostly funny songs, while Rafi sang romantic numbers, Mukesh,sad songs…and Manna Dey, classical songs. During the past twenty years, I have journeyed a lot, both in music as well as in life. And many of my childhood heroes have diminished in stature over the years. But a few…..a precious few….have grown……. steadily….and continue to grow, each time I am exposed to their brilliance. M.D.Ramanathan, Martina Navratilova, Bruce Lee, Swami Vivekananda, Kunchan Nambiar, to name a few…..and Kishore Kumar. I have had the privilege of studying classical music for more than two and a half decades from some truly phenomenal Gurus and I go around giving lecture demonstrations about how important it is for a singer to know an instrument and vice versa. -

Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Maiti, Rashmila, "Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2905. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Rashmila Maiti Jadavpur University Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, 2007 Jadavpur University Master of Arts in English Literature, 2009 August 2018 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. M. Keith Booker, PhD Dissertation Director Yajaira M. Padilla, PhD Frank Scheide, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This project analyzes adaptation in the Hindi film industry and how the concepts of gender and identity have changed from the original text to the contemporary adaptation. The original texts include religious epics, Shakespeare’s plays, Bengali novels which were written pre- independence, and Hollywood films. This venture uses adaptation theory as well as postmodernist and postcolonial theories to examine how women and men are represented in the adaptations as well as how contemporary audience expectations help to create the identity of the characters in the films. -

A Study of Shakespeare Contribution in Hindi Cinema

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2016): 79.57 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 A Study of Shakespeare Contribution in Hindi Cinema Asma Qureshi Abstract: In India, Cinema not only a name of entertainment, but also educate to millions of people every day. Friday is celebrated by screening of new films. Indians happily participate in Cinema culture of the Country. Shakespearean tragedies have been a never ending source of inspiration for all filmmakers across the world. Many Hindi films based on Shakespeare novel like Shahid, Omkara, Goliyo ki raasleela Ramleela etc. William Shakespeare in India has been an exceptional and ground-breaking venture. The literary collection of Shakespeare is dynamic and an unlimited source of inspiration for countless people across the globe. When Shakespeare’s writing is adapted in cinema, it sets it ablaze, and transfers the audience to a cinematic paradise. Indian adaptation of both Shakespearean tragedy and comedy can be comprehended as an Combination of ‘videsi’ and ‘desi’, a synthesis of East and West, and an Oriental and Occidental cultural exchange. Shakespeare’s, “bisexual‟ mind, the complexity of his Narrative, music, story-telling, and creative sensibility categorizes him as an ace literary craftsman. This Research is an attempt to understand the contribution of Shakespeare novel in Hindi cinema. So that we can easily understand the main theme of the story. What writer wants to share with us. We can easily understand main theme of novel. 1. Introduction European library worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia‖. It also has a lot to do with profound resonances Indian Hindi language film industry is also known as Hindi between Shakespeare‘s craft and Indian cultural forms that cinema which is situated or we can say mainly operated converge on one concept: masala. -

Volume 1 on Stage/ Off Stage

lives of the women Volume 1 On Stage/ Off Stage Edited by Jerry Pinto Sophia Institute of Social Communications Media Supported by the Laura and Luigi Dallapiccola Foundation Published by the Sophia Institute of Social Communications Media, Sophia Shree B K Somani Memorial Polytechnic, Bhulabhai Desai Road, Mumbai 400 026 All rights reserved Designed by Rohan Gupta be.net/rohangupta Printed by Aniruddh Arts, Mumbai Contents Preface i Acknowledgments iii Shanta Gokhale 1 Nadira Babbar 39 Jhelum Paranjape 67 Dolly Thakore 91 Preface We’ve heard it said that a woman’s work is never done. What they do not say is that women’s lives are also largely unrecorded. Women, and the work they do, slip through memory’s net leaving large gaps in our collective consciousness about challenges faced and mastered, discoveries made and celebrated, collaborations forged and valued. Combating this pervasive amnesia is not an easy task. This book is a beginning in another direction, an attempt to try and construct the professional lives of four of Mumbai’s women (where the discussion has ventured into the personal lives of these women, it has only been in relation to the professional or to their public images). And who better to attempt this construction than young people on the verge of building their own professional lives? In learning about the lives of inspiring professionals, we hoped our students would learn about navigating a world they were about to enter and also perhaps have an opportunity to reflect a little and learn about themselves. So four groups of students of the post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media, SCMSophia’s class of 2014 set out to choose the women whose lives they wanted to follow and then went out to create stereoscopic views of them. -

Agha Hashar Kashmiri - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Agha Hashar Kashmiri - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Agha Hashar Kashmiri(03 April 1879 -28 April 1945) Agha Hashar Kashmiri or Agha Hashr Kashmiri (Urdu: ??? ??? ???????) was an eminent Urdu poet, playwright and dramatist. He was also called the Shakespeare of Urdu. <b> Biography </b> Agha Hashar Kashmiri was born on 3 April 1879, in Banaras, British India. He got his initial Education there .He could not get a higher education due to lack of interest in text books. Since child hood he was interested in poetry,music but after watching few stage drammas his mind was changed toward his field. He came to Bombay at the age of 18 and started his career as a play had a full command on more than one language but familiar wid Urdu, Arabic, persian, English, Gujrati and Hindi. His first play, Aftab-e-Muhabat, was published in 1897. He started his professional career as a drama writer in the New Alfred theatrical company in Bombay, on a salary of Rs. 15 per month. Murid-e-Shak, his first play for the company, was an adaptation of Shakespeare's play The Winter's Tale. It proved a success and his wages were raised to Rs. 40 per month thereafter. In his works, Agha had experience introducing shorter songs and dialogues with idioms and poetic virtues in plays. Later, he created the Shakespeare theatrical company but could not stay in business for long. He also joined Maidan theatre – a tented theatre to accommodate large audiences – where he earned a credible name in Urdu drama and poetry. -

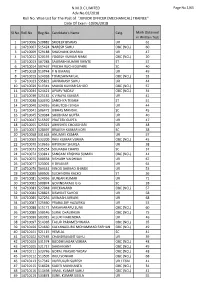

N.M.D.C LIMITED Adv.No.02/2018 Roll No. Wise List for the Post Of

N.M.D.C LIMITED Page No.1/65 Adv.No.02/2018 Roll No. Wise List for The Post of "JUNIOR OFFICER (MECHANICAL) TRAINEE" Date Of Exam ‐10/06/2018 Sl.No. Roll.No. Reg.No. Candidate's Name Catg. Mark Obtained in Written Test 1 14710006 520882 SRIDEEP BISWAS UR 61 2 14710007 515424 NARESH SAHU OBC (NCL) 60 3 14710009 529188 SHASHANK SHARMA UR 47 4 14710012 520155 YOGESH KUMAR NIMJE OBC (NCL) 20 5 14710013 507288 SAURABH KUMAR RAWTE ST 57 6 14710014 507467 PRICHA RUCHI DUPARE SC 40 7 14710018 519744 P N UMANG UR 49 8 14710019 524958 TOMESHWAR LAL OBC (NCL) 33 9 14710023 535821 JAIPRAKASH SAHU UR 44 10 14710029 519341 MANOJ KUMAR SAHOO OBC (NCL) 57 11 14710034 524621 APURV YADAV OBC (NCL) 34 12 14710036 525142 K VINAYA KUMAR UR 41 13 14710038 533370 SANDHYA TEKAM ST 51 14 14710040 524916 ASHUTOSH SINGH UR 44 15 14710041 506472 BIBHAS MANDAL SC 45 16 14710045 520384 SHUBHAM GUPTA UR 40 17 14710047 515597 PRATEEK GUPTA UR 47 18 14710055 525321 ABHISHEK CHOUDHARI UR 48 19 14710057 528697 BRAJESH KUMAR KORI SC 38 20 14710058 531663 ANUMAY KUMAR UR 57 21 14710069 532209 RAVI KUMAR VERMA OBC (NCL) 45 22 14710070 510616 RIPUNJAY SHUKLA UR 38 23 14710073 535254 SOURABH CHAPDI SC 37 24 14710074 533811 SANGAM KRISHNA SUMAN OBC (NCL) 44 25 14710075 500658 RISHABH VAISHNAV UR 67 26 14710077 523001 V DIVAKAR UR 64 27 14710079 509441 VINOD BAJIRAO SHINDE UR 53 28 14710080 500505 SUCHINDRA XALXO ST 36 29 14710081 524956 GUNJAN KUMAR UR 71 30 14710082 500874 GOVINDARAJU G GSC28 31 14710083 527048 VIVEKANAND OBC (NCL) 57 32 14710084 528823 BISWOJIT SAHOO UR 58 -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

Dossier-De-Presse-L-Ombrelle-Bleue

Splendor Films présente Synopsis Dans un petit village situé dans les montagnes de l’Himalaya, une jeune fille, Biniya, accepte d’échanger son porte bonheur contre une magnifique ombrelle bleue d’une touriste japonaise. Ne quittant plus l’ombrelle, l’objet L’Ombrelle semble lui porter bonheur, et attire les convoitises des villageois, en particulier celles de Nandu, le restaurateur du village, pingre et coléreux. Il veut à tout prix la récupérer, mais un jour, l’ombrelle disparaît, et Biniya bleue mène son enquête... Note de production un film de Vishal Bhardwaj L’Ombrelle bleue est une adaptation cinématographique très fidèle à la nouvelle éponyme de Ruskin Bond. Le film a été tourné dans la région de l’Himachal Pradesh, située au nord de l’Inde, à la frontière de la Chine et Inde – 2005 – 94 min – VOSTFR du Pakistan, dans une région montagneuse. La chaîne de l’Himalaya est d’ailleurs le décor principal du film, le village est situé à flanc de montagne. Inédit en France L’Ombrelle bleue reprend certains codes et conventions des films de Bollywood. C’est pourtant un film original dans le traitement de l’histoire. Alors que la plupart des films de Bollywood durent près de trois heures et traitent pour la plupart d’histoires sentimentales compliquées par la religion et les obligations familiales, L’Ombrelle bleue s’intéresse davantage aux caractères de ses personnages et à la nature environnante. AU CINÉMA Le film, sorti en août 2007 en Inde, s’adresse aux enfants, et a pour LE 16 DÉCEMBRE vedettes Pankaj Kapur et Shreya Sharma. -

Othello and Its Rewritings, from Nineteenth-Century Burlesque to Post- Colonial Tragedy

Black Rams and Extravagant Strangers: Shakespeare’s Othello and its Rewritings, from Nineteenth-Century Burlesque to Post- Colonial Tragedy Catherine Ann Rosario Goldsmiths, University of London PhD thesis 1 Declaration I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. 2 Acknowledgements Firstly, I want to thank my supervisor John London for his immense generosity, as it is through countless discussions with him that I have been able to crystallise and evolve my ideas. I should also like to thank my family who, as ever, have been so supportive, and my parents, in particular, for engaging with my research, and Ebi for being Ebi. Talking things over with my friends, and getting feedback, has also been very helpful. My particular thanks go to Lucy Jenks, Jay Luxembourg, Carrie Byrne, Corin Depper, Andrew Bryant, Emma Pask, Tony Crowley and Gareth Krisman, and to Rob Lapsley whose brilliant Theory evening classes first inspired me to return to academia. Lastly, I should like to thank all the assistance that I have had from Goldsmiths Library, the British Library, Senate House Library, the Birmingham Shakespeare Collection at Birmingham Central Library, Shakespeare’s Birthplace Trust and the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive. 3 Abstract The labyrinthine levels through which Othello moves, as Shakespeare draws on myriad theatrical forms in adapting a bald little tale, gives his characters a scintillating energy, a refusal to be domesticated in language. They remain as Derridian monsters, evading any enclosures, with the tragedy teetering perilously close to farce. Because of this fragility of identity, and Shakespeare’s radical decision to have a black tragic protagonist, Othello has attracted subsequent dramatists caught in their own identity struggles. -

Psychoanalysis of Female Characters in Vishal Bharadwaj's Trilogy

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Psychoanalysis of Female Characters in Vishal Bharadwaj’s Trilogy Maqbool, Omkara and Haider Shikha Rani, Research Scholar MJP Rohilkhand University Bareilly Alka Mehra Assistant Professor Government Degree College Bisalpur MJP Rohilkhand University Bareilly Abstract: Freud’s theory of psychology that he referred as psychoanalysis has been accepted and extended in analyzing literature and other arts too. Freud believes that literature and other arts are like dreams and psycho symptoms which contain imaginative fancies, so literature and other arts are capable to fulfill wishes that are commonly restricted by social standards and norms. My research paper is an attempt to focus on the psychoanalysis of female protagonists in Bharadwaj’s worldwide acclaimed movies ‘Maqbool’, ‘Omkara’ and ‘Haider’ which are an adaptation of Shakespeare’s famous tragedies ‘Macbeth’, ‘Othello’ and ‘Hamlet’. These female characters are just like puppet in grip of unconscious urges. This study further analysis human’s helplessness under the arrest of its uncontrolled passions. Through this study, I want to find out the strong and weak unconscious fancies of Nimmi, Dolly and Gazala and their fight against their own id, ego and superego which brutally influenced them mentally as well as physically. Nimmi who is a complex character, struggles as a mistress of don and as a beloved of Maqbool. Dolly suffers mentally due to male’s suspicious nature and patriarchal society whereas Gazala tries to make conciliation with her second marriage and with her adult obsessive son. Keyword: psychoanalysis, sex complex obsessive, conflict. Shakespeare’s plays have been adapted all over the world due to his universality and cosmopolitan nature. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994.