The Serpent River First Nation and Uranium Mining, 1953

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Physical Environment City Greater Sudbury

Physical Environment–Sudbury; OGS Special Volume 6 Selected Headings for Chapter 9, The Past, Present and Future of Sudbury’s Lakes Abstract......................................................................................................................................................... 195 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 195 Geological Control of Sudbury’s Lakes ....................................................................................................... 195 Watersheds and Watershed Units ................................................................................................................. 198 Watersheds in the City ........................................................................................................................... 198 Watershed Units ..................................................................................................................................... 199 Environmental History and Prognosis .......................................................................................................... 199 Pre-Settlement ........................................................................................................................................ 199 The Impact of Industrial Environmental Stresses .................................................................................. 199 Erosion............................................................................................................................................ -

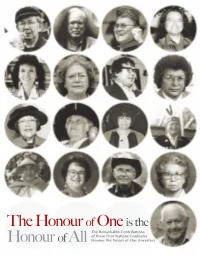

The Honour of One Is the the Remarkable Contributions of These First Nations Graduates Honour of All Honour the Voices of Our Ancestors Table of Contents of Table

The Honour of One is the The Remarkable Contributions of these First Nations Graduates Honour of All Honour the Voices of Our Ancestors 2 THE HONOUR OF ONE Table of Contents 3 Table of Contents 2 THE HONOUR OF ONE Introduction 4 William (Bill) Ronald Reid 8 George Manuel 10 Margaret Siwallace 12 Chief Simon Baker 14 Phyllis Amelia Chelsea 16 Elizabeth Rose Charlie 18 Elijah Edward Smith 20 Doreen May Jensen 22 Minnie Elizabeth Croft 24 Georges Henry Erasmus 26 Verna Jane Kirkness 28 Vincent Stogan 30 Clarence Thomas Jules 32 Alfred John Scow 34 Robert Francis Joseph 36 Simon Peter Lucas 38 Madeleine Dion Stout 40 Acknowledgments 42 4 THE HONOUR OF ONE IntroductionIntroduction 5 THE HONOUR OF ONE The Honour of One is the Honour of All “As we enter this new age that is being he Honour of One is the called “The Age of Information,” I like to THonour of All Sourcebook is think it is the age when healing will take a tribute to the First Nations men place. This is a good time to acknowledge and women recognized by the our accomplishments. This is a good time to University of British Columbia for share. We need to learn from the wisdom of their distinguished achievements and our ancestors. We need to recognize the hard outstanding service to either the life work of our predecessors which has brought of the university, the province, or on us to where we are today.” a national or international level. Doreen Jensen May 29, 1992 This tribute shows that excellence can be expressed in many ways. -

By Anne Millar

Wartime Training at Canadian Universities during the Second World War Anne Millar Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate of Philosophy degree in history Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Anne Millar, Ottawa, Canada, 2015 ii Abstract This dissertation provides an account of the contributions of Canadian universities to the Second World War. It examines the deliberations and negotiations of university, government, and military officials on how best to utilize and direct the resources of Canadian institutions of higher learning towards the prosecution of the war and postwar reconstruction. During the Second World War, university leaders worked with the Dominion Government and high-ranking military officials to establish comprehensive training programs on campuses across the country. These programs were designed to produce service personnel, provide skilled labour for essential war and civilian industries, impart specialized and technical knowledge to enlisted service members, and educate returning veterans. University administrators actively participated in the formation and expansion of these training initiatives and lobbied the government for adequate funding to ensure the success of their efforts. This study shows that university heads, deans, and prominent faculty members eagerly collaborated with both the government and the military to ensure that their institutions’ material and human resources were best directed in support of the war effort and that, in contrast to the First World War, skilled graduates would not be heedlessly wasted. At the center of these negotiations was the National Conference of Canadian Universities, a body consisting of heads of universities and colleges from across the country. -

Writing Alberta POD EPDF.Indd

WRITING ALBERTA: Aberta Building on a Literary Identity Edited by George Melnyk and Donna Coates ISBN 978-1-55238-891-4 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. If you want to reuse or distribute the work, you must inform its new audience of the licence terms of this work. -

Introduction One Setting the Stage

Notes Introduction 1. For further reference, see, for example, MacKay 2002. 2. See also Engle 2010 for this discussion. 3. I owe thanks to Naomi Kipuri, herself an indigenous Maasai, for having told me of this experience. 4. In the sense as this process was first described and analyzed by Fredrik Barth (1969). 5. An in-depth and updated overview of the state of affairs is given by other sources, such as the annual IWGIA publication, The Indigenous World. 6. The phrase refers to a 1972 cross-country protest by the Indians. 7. Refers to the Act that extinguished Native land claims in almost all of Alaska in exchange for about one-ninth of the state’s land plus US$962.5 million in compensation. 8. Refers to the court case in which, in 1992, the Australian High Court for the first time recognized Native title. 9. Refers to the Berger Inquiry that followed the proposed building of a pipeline from the Beaufort Sea down the Mackenzie Valley in Canada. 10. Settler countries are those that were colonized by European farmers who took over the land belonging to the aboriginal populations and where the settlers and their descendents became the majority of the population. 11. See for example Béteille 1998 and Kuper 2003. 12. I follow the distinction as clarified by Jenkins when he writes that “a group is a collectivity which is meaningful to its members, of which they are aware, while a category is a collectivity that is defined according to criteria formu- lated by the sociologist or anthropologist” (2008, 56). -

Geology of the Wakomata Lake Area; District of Algoma

THESE TERMS GOVERN YOUR USE OF THIS DOCUMENT Your use of this Ontario Geological Survey document (the “Content”) is governed by the terms set out on this page (“Terms of Use”). By downloading this Content, you (the “User”) have accepted, and have agreed to be bound by, the Terms of Use. Content: This Content is offered by the Province of Ontario’s Ministry of Northern Development and Mines (MNDM) as a public service, on an “as-is” basis. Recommendations and statements of opinion expressed in the Content are those of the author or authors and are not to be construed as statement of government policy. You are solely responsible for your use of the Content. You should not rely on the Content for legal advice nor as authoritative in your particular circumstances. Users should verify the accuracy and applicability of any Content before acting on it. MNDM does not guarantee, or make any warranty express or implied, that the Content is current, accurate, complete or reliable. MNDM is not responsible for any damage however caused, which results, directly or indirectly, from your use of the Content. MNDM assumes no legal liability or responsibility for the Content whatsoever. Links to Other Web Sites: This Content may contain links, to Web sites that are not operated by MNDM. Linked Web sites may not be available in French. MNDM neither endorses nor assumes any responsibility for the safety, accuracy or availability of linked Web sites or the information contained on them. The linked Web sites, their operation and content are the responsibility of the person or entity for which they were created or maintained (the “Owner”). -

CMD 18-M48.9A File/Dossier : 6.02.04 Date

CMD 18-M48.9A File/dossier : 6.02.04 Date : 2018-12-03 Edocs pdf : 5725730 Revised written submission from Mémoire révisé de Northwatch Northwatch In the Matter of À l’égard de Regulatory Oversight Report for Uranium Rapport de surveillance réglementaire des Mines, Mills, Historic and Decommissioned mines et usines de concentration d’uranium et Sites in Canada: 2017 des sites historiques et déclassés au Canada : 2017 Commission Meeting Réunion de la Commission December 12, 2018 Le 12 décembre 2018 Revised version with changes made on pages 5 and 6 November 20, 2018 Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission 280 Slater Street, P.O. Box 1046, Station B Ottawa, ON K1P 5S9 Ref. CMD 18-M48 Dear President Velshi and Commission Members: Re. Regulatory Oversight Report for Uranium Mines, Mills, Historic and Decommissioned Sites in Canada: 2017 On 29 June 2018 the Secretariat for the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission provided notice that the Commission would hold a public meeting in December 2018 during which CNSC staff will present its Regulatory Oversight Report for Uranium Mines, Mills, Historic and Decommissioned Sites in Canada: 2017. The notice further indicated that the Report would be available after October 12, 2018, online or by request to the Secretariat, and that members of the public who have an interest or expertise on this matter are invited to comment, in writing, on the Report by November 13 2017. Northwatch provides these comments further to that Notice. Northwatch appreciates the extension of the deadline for submission of our comments by one week in response to delays in finalizing the contribution agreement which had to be in place prior to our technical experts beginning their review. -

2020 Summer of Adventure! LAKE HURON NORTH CHANNEL Massey to Espanola

2020 Summer of Adventure! LAKE HURON NORTH CHANNEL Massey to Espanola 2020 Summer of Adventure! LAKE HURON NORTH CHANNEL-Massey to Espanola Celebrate 25years of trail-building and work to protect and connect our Great Lakes and St. Lawrence waterfront with the 2020 Summer of Adventure! This week we head north with a wonderful ride from Massey to Espanola. Never mind the Big Smoke. Welcome to big northern hospitality. Ride through the gentle foothills of the ancient LaCloche mountain range, experience the breathtaking beauty of the falls at Chutes Provincial Park, swim in the Spanish River, take a dip into Espanola’s Clear Lake, learn about the region’s colourful heritage at local museums. Terrain—Easy terrain, flat paved roadway. Lee Valley Road is very quiet. The 30 km between Massey and Espanola does not have any services—just lovely landscape. Distance—32 km from Chutes Provincial Park, Massey to Clear Lake Beach in Espanola. Start in either Espanola or Massey. Both have a variety of accommodations. Chutes Provincial Park is open. During Covid, it is operating with some restrictions. We suggest spending a day or two in each community to enjoy all they have to offer. With 3 beach opportunities, this adventure is ideal for the beach-loving. Township of Sables-Spanish Rivers — Massey You’ll find tranquil northern roads guiding you through the LaCloche foothills and dancing along shores of the serene Spanish River as the Trail winds through the Township of Sables-Spanish Rivers. The Township is centred in Massey, a welcoming community with a variety of excellent local restaurants and eateries, a pair of motels, a quaint craft store and coffee shop, a fascinating local museum, a grocer, one of the most generous scoops of ice cream around, and a road that is (quite literally) Seldom Seen. -

Proudly Representing Ontario's Community Newspapers 310

We deliver Ontario - in PRINT and ONLINE! Reach engaged and involved Ontarians in just one call, one buy, one invoice Proudly Representing Ontario’s Community Newspapers * 310 newspapers reaching 5.8 million households NOW Ad*Reach represents their Online Community News Sites! 190 Community News Sites with Average* Monthly Impressions of 12 Million. Advertise on All Ontario sites or through a combination of geographic zones Rates: Specs: $17 CPM Net Per Order * Leaderboard ads (728 x 90 pixels) Volume Rates Available * File size up to 40 kilobyte, in gif, * Book All Ontario sites, jpg or standard flash format or a combination of geographic zones * Ads published Run of Site (ROS) * Bookings and ad material must be received 5 days prior to launch Let us assist you in your campaign planning Ad*Reach Ontario (adreach.ca) CallTed us Brewer at 905.639.8720 or Minnawww.adreach.ca Schmidt emailNational [email protected] Account Manager Manager of Sales 416-350-2107 ext 24 416-350-2107 ext 22 [email protected] [email protected] A division of the Ontario Community Newspapers Association Ontario's Local Community News Sites Zone Community News URL Associated Community Newspaper ALL OF ONTARIO 190 Newspapers Average Monthly Impressions 12 Million Or A Combination Of: ZONE 1 ‐ SOUTHWEST ONTARIO amherstburgecho.com Amherstburg Echo 40 Newspapers northhuron.on.ca Blyth/Brussels Citizen Average Monthly cambridgetimes.ca Cambridge Times Impressions chathamthisweek.com Chatham This Week 908,000 clintonnewsrecord.com Clinton News Record delhinewsrecord.com -

The Canadian Field-Naturalist

The Canadian Field-Naturalist Volume 129, Number 2 April –June 2 015 Using an Integrated Recording and Sound Analysis System to Search for Kirtland’s Warbler ( Setophaga kirtlandii ) in Ontario STEPHEN B. H OLMES 1, 2, 6 ,KEN TUININGA 3, K ENNETH A. M CILWRICK 1, M ARGARET CARRUTHERS 4, and ERIC COBB 5 1Canadian Forest Service, Natural Resources Canada, 1219 Queen St. E., Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario P6A 2E5 Canada 2Current address: 23 Atlas St., Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario P6A 4Z2 Canada 3Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, 4905 Dufferin St., Toronto, Ontario M3H 5T4 Canada 4Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Sault Ste. Marie District, 64 Church St., Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario P6A 3H3 Canada 5Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, North Bay District, 3301 Trout Lake Road, North Bay, Ontario P1A 4L7 Canada 6Corresponding author: [email protected] Holmes, Stephen B., Ken Tuininga, Kenneth A. McIlwrick, Margaret Carruthers, and Eric Cobb. 2015. Using an integrated recording and sound analysis system to search for Kirtland’s Warbler ( Setophaga kirtlandii ) in Ontario. Canadian Field-Naturalist 129(2): 115–120. We used automated sound recording devices and analysis software to search for Kirtland’s Warbler ( Setophaga kirtlandii ) in northeastern Ontario. In 2012, we conducted surveys at 38 locations in three Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources adminis - trative districts: Chapleau, Sault Ste. Marie, and Sudbury. We detected a Kirtland’s Warbler at one location in Sault Ste. Marie District on a single date: June 6. We believe that the recording and analysis approach we used is an effective method for detecting Kirtland’s Warbler, or other rare bird species, across extensive areas of their potential range. -

STAGE 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT QUIRKE LAKE PROPERTY DEVELOPMENT Buckles Township, on City of Elliot Lake District of Algoma PIF# P041-168-2012

STAGE 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT QUIRKE LAKE PROPERTY DEVELOPMENT Buckles Township, ON City of Elliot Lake District of Algoma PIF# P041-168-2012 Submitted to: Rhona Guertin Manager Finance & Business Development Elliot Lake Retirement Living 289 Highway 108 Elliot Lake, ON P5A 2S9 Phone: (705) 848-4911 ext 254 E-mail: [email protected] PIF # P041-168-2012 Dr. David J.G. Slattery (License number P041) Horizon Archaeology Inc. 220 Chippewa St. W. North Bay, ON P1B 6G2 Phone: (705) 474-3864 Fax: (705) 474-5626 E-mail: [email protected] Date of Filing: March 20, 2013 Type of Report: Original EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Horizon Archaeology Inc. was contacted by Elliot Lake Retirement Living to conduct a Stage 1 Archaeological Assessment of the proposed Quirke Lake development in Buckles Township. This report describes the methodology and results of the Stage 1 Archaeological Assessment of the Quirke Lake property which are around the shores of Quirke Lake, in Buckles Township, City of Elliot Lake. This study was conducted under the Archaeological Consulting License P- 041 issued to David J.G. Slattery by the Minister of Tourism, Culture and Sport for the Province of Ontario. This assessment was undertaken in order to recover and assess the cultural heritage value or interest of any archaeological sites within the project boundaries. All work was conducted in conformity with the Ontario Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport (MTCS) Standards and Guidelines for Consultant Archaeologists (MTCS 2011), and the Ontario Heritage Amendment Act (SO 2005). Horizon Archaeology Inc. was engaged by the proponent to undertake a Stage 1 Archaeological Assessment of the study area and was granted permission to carry out archaeological fieldwork by the owner’s representative. -

GWTA 2019 Overview and Participant Survey Monday, August 26, 2019

GWTA 2019 Overview and Participant Survey Monday, August 26, 2019 Powered by Cycle the North! GWTA 2019-July 28 to August 2 450km from Sault Ste. Marie to Sudbury launching the Lake Huron North Channel Expansion of the Great Lakes Waterfront Trail and Great Trail. Overnight Host Communities: Sault Ste. Marie, Bruce Mines, Blind River, Espanola, Sudbury Rest Stop Hosts: Garden River First Nation, Macdonald Meredith and Aberdeen Additional (Echo Bay), Johnson Township (Desbarats), Township of St. Joseph, Thessalon, Huron Shores (Iron Bridge), Mississauga First Nation, North Shore Township (AlgoMa Mills), Serpent River First Nation, Spanish, Township of Spanish-Sables (Massey), Nairn Centre. 150 participants aged 23 to 81 coming from Florida, Massasschutes, Minnesota, New Jersey, Arizona, and 5 provinces: Ontario (91%), British ColuMbia, Alberta, Quebec and New Brunswick. 54 elected representatives and community leaders met GWTA Honorary Tour Directors and participants at rest stops and in soMe cases cycled with the group. See pages 24-26 for list. Special thanks to our awesome support team: cycling and driving volunteers, caMp teaM, Mary Lynn Duguay of the Township of North Shore for serving as our lead vehicle and Michael Wozny for vehicle support. Great regional and local Media coverage. 2 The Route—Lake Huron North Channel Expansion—450 km from Gros Cap to Sudbury Gichi-nibiinsing-zaaga’igan Ininwewi-gichigami Waaseyaagami-wiikwed Naadowewi-gichigami Zhooniyaang-zaaga’igan Gichigami-zitbi Niigani-gichigami Waawiyaataan Waabishkiigoo-gichigami • 3000 km, signed route The Lake Huron North Channel celebrates the spirit of the North, following 12 heritage• 3 rivers,Great Lakes,connecting 5 bi- nationalwith 11 northern rivers lakes, • 140 communities and First Nations winding through forests, AMish and Mennonite farmland, historic logging, Mining and• fishing3 UNESCO villages, Biospheres, and 24 beaches.