The Canadian Field-Naturalist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Horan Family Diaspora Since Leaving Ireland 191 Years Ago

A Genealogical Report on the Descendants of Michael Horan and Mary Minnock by A.L. McDevitt Introduction The purpose of this report is to identify the descendants of Michael Horan and Mary Minnock While few Horans live in the original settlement locations, there are still many people from the surrounding areas of Caledon, and Simcoe County, Ontario who have Horan blood. Though heavily weigh toward information on the Albion Township Horans, (the descendants of William Horan and Honorah Shore), I'm including more on the other branches as information comes in. That is the descendants of the Horans that moved to Grey County, Ontario and from there to Michigan and Wisconsin and Montana. I also have some information on the Horans that moved to Western Canada. This report was done using Family Tree Maker 2012. The Genealogical sites I used the most were Ancestry.ca, Family Search.com and Automatic Genealogy. While gathering information for this report I became aware of the importance of getting this family's story written down while there were still people around who had a connection with the past. In the course of researching, I became aware of some differences in the original settlement stories. I am including these alternate versions of events in this report, though I may be personally skeptical of the validity of some of the facts presented. All families have myths. I feel the dates presented in the Land Petitions of Mary Minnock and the baptisms in the County Offaly, Ireland, Rahan Parish registers speak for themselves. Though not a professional Genealogist, I have the obligation to not mislead other researchers. -

The Canadian Parliamentary Guide

NUNC COGNOSCO EX PARTE THOMAS J. BATA LI BRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY us*<•-« m*.•• ■Jt ,.v<4■■ L V ?' V t - ji: '^gj r ", •W* ~ %- A V- v v; _ •S I- - j*. v \jrfK'V' V ■' * ' ’ ' • ’ ,;i- % »v • > ». --■ : * *S~ ' iJM ' ' ~ : .*H V V* ,-l *» %■? BE ! Ji®». ' »- ■ •:?■, M •* ^ a* r • * «'•# ^ fc -: fs , I v ., V', ■ s> f ** - l' %% .- . **» f-•" . ^ t « , -v ' *$W ...*>v■; « '.3* , c - ■ : \, , ?>?>*)■#! ^ - ••• . ". y(.J, ■- : V.r 4i .» ^ -A*.5- m “ * a vv> w* W,3^. | -**■ , • * * v v'*- ■ ■ !\ . •* 4fr > ,S<P As 5 - _A 4M ,' € - ! „■:' V, ' ' ?**■- i.." ft 1 • X- \ A M .-V O' A ■v ; ■ P \k trf* > i iwr ^.. i - "M - . v •?*»-• -£-. , v 4’ >j- . *•. , V j,r i 'V - • v *? ■ •.,, ;<0 / ^ . ■'■ ■ ,;• v ,< */ ■" /1 ■* * *-+ ijf . ^--v- % 'v-a <&, A * , % -*£, - ^-S*.' J >* •> *' m' . -S' ?v * ... ‘ *•*. * V .■1 *-.«,»'• ■ 1**4. * r- * r J-' ; • * “ »- *' ;> • * arr ■ v * v- > A '* f ' & w, HSi.-V‘ - .'">4-., '4 -' */ ' -',4 - %;. '* JS- •-*. - -4, r ; •'ii - ■.> ¥?<* K V' V ;' v ••: # * r * \'. V-*, >. • s s •*•’ . “ i"*■% * % «. V-- v '*7. : '""•' V v *rs -*• * * 3«f ' <1k% ’fc. s' ^ * ' .W? ,>• ■ V- £ •- .' . $r. « • ,/ ••<*' . ; > -., r;- •■ •',S B. ' F *. ^ , »» v> ' ' •' ' a *' >, f'- \ r ■* * is #* ■ .. n 'K ^ XV 3TVX’ ■■i ■% t'' ■ T-. / .a- ■ '£■ a« .v * tB• f ; a' a :-w;' 1 M! : J • V ^ ’ •' ■ S ii 4 » 4^4•M v vnU :^3£'" ^ v .’'A It/-''-- V. - ;ii. : . - 4 '. ■ ti *%?'% fc ' i * ■ , fc ' THE CANADIAN PARLIAMENTARY GUIDE AND WORK OF GENERAL REFERENCE I9OI FOR CANADA, THE PROVINCES, AND NORTHWEST TERRITORIES (Published with the Patronage of The Parliament of Canada) Containing Election Returns, Eists and Sketches of Members, Cabinets of the U.K., U.S., and Canada, Governments and Eegisla- TURES OF ALL THE PROVINCES, Census Returns, Etc. -

SUMMER 2020 Contents

SUMMER 2020 Contents IN LOVING MEMORY OF Dr. Stuart Smith 3 to 5 FEATURES Positivity in a Pandemic 6 to 9 Culinary Corner 10 to 11 Touring Southwestern Ontario 12 to 14 INTERVIEWS George Taylor 15 to 17 Mavis Wilson 18 to 20 Bud Wildman 21 to 24 OBITURARIES Robert Walter Elliot 25 to 26 Dr. Jim Henderson 27 to 28 Bill Barlow 29 to 31 The InFormer In Loving Memory of Dr. Stuart Smith (May 7, 1938 – June 10, 2020) Served in the 31st, 32nd and 33rd Parliaments (September 18, 1975 – January 24, 1982) Liberal Member of Provincial Parliament for Hamilton-West Dr. Stuart Smith served as Leader of the Ontario Liberal Party from January 25, 1976 to January 24, 1982. Student Days at McGill University President, McGill Student Society Winner of Reefer Cup (Debating) 1957: Organized a student strike against the Maurice Duplessis government 1962: One of 5 university students chosen from across Canada to participate in the first exchange with students from the Soviet Union Co-hosted CBC program “Youth Special” produced in Montreal in the early 1960s. Science, Technology, Medicine and Education Chair, Board of Governors, University of Guelph-Humber 1982-87: Chair, Science Council of Canada 1991: Chair, Smith Commission - state of post-secondary education in Canada 1995-2002: Chair of the National Roundtable on the Environment and the Economy Founded Rockcliffe Research and Technology Inc. Director of Esna Technologies Director and long-time Chair of the Board of Ensyn Technologies As a physician at McMaster University he presented “This is Psychiatry” on CHCH-TV Continued .. -

Services Directory

UPDATED JANUARY 2019 Services Directory DISCOVER WHAT ELLIOT LAKE HAS TO OFFER CITYwww.cityofelliotlake.com SERVICES • CLUBS • HEALTH SERVICES • SCHOOLSCity of Elliot & MORE Lake Elliot Lake is a clean, modern city that combines the hospitality of a small town with the services of a large centre. The pristine wilderness and thousands of lakes just beyond the city limits provide countless opportunities for hiking, camping and world class fishing. Within the City there are many services, clubs and organizations. This directory is aimed to provide information on what is available locally for current residents as well as those new to the community. For a complete list of businesses, retail, restaurants, etc. please visit the Business Directory on our website at www.cityofelliotlake.com. For recommendations on changes or additions ot this booklet, please contact the Community Development Officer at 705-848-2287 ext. 2135. City of Elliot Lake 2 www.cityofelliotlake.com Table of Contents City Departments …………………………………......…. Page 4 Parks & Beaches ……………………………………………. Page 5 Health Services ……………………………….......…..….. Page 6 Clubs/Recreation ……………………………….....….….. Page 8 Services/Agencies ………………………..……...……... Page 12 Day Cares …………………....…………………...…….….. Page 14 Elementary Schools ………………….………..……….. Page 14 Secondary Schools ……………………..……..…….….. Page 14 Accommodations & Campgrounds ……...….…... Page 15 Utilities ………………..……………………..…….…….….. Page 15 Places of Worship …………..…..…...……….…….….. Page 16 www.cityofelliotlake.com 3 City of Elliot Lake City Departments DEPARTMENT CONTACT INFORMATION Airport (705) 461-7222 Ambulance (705) 848-4444 Animal Control (705) 848-2287 ext. 2122 Arts & Culture (705) 848-2287 ext. 2400 Building Department (705) 848-2287 ext. 2119 By-law Enforcement (705) 848-2287 ext. 2122 Cemetery (705) 848-2287 ext. 2103 Centennial Arena (705) 461-7215 City Clerk (705) 848-2287 ext. -

Electoral Districts, Voters on List and Votes Polled, Names and Addresses of Members of the House of Commons As Elected at the Twenty-Sixth General Election, Apr

72 CONSTITUTION AND GOVERNMENT 10.—Electoral Districts, Voters on List and Votes Polled, Names and Addresses of Members of the House of Commons as Elected at the Twenty-Sixth General Election, Apr. 8,1963 and Revised to Apr. 30,1964r—continued. Votes Province Popu Total Polled lation, Voters and on Votes by Name of Member P.O. Address Census Polled Electoral District 1961 List Mem ber No. No. No. No. Quebec—concluded Montreal and Jesus Islands— Cartier 51,819 19,944 13,842 6,642 M. L. KLEIN. Montreal.... Dollard 107,394 58,212 41,808 23.764 G. ROULEAU.. Montreal Hochelaga 79,912 46,587 28,717 13,093 R. EUDES. ... Montreal Jacques-Cartier- Lasalle 163,148 94,681 76,086 44,299 R. ROCK Lachine Lafontaine 50,325 31,411 21,975 10,929 G.-C. LACHANCE Montreal Laurier 45.652 26,870 18,226 8,059 Hon. L. CHEVRIER1. Ottawa, Ont. Laval 193,437 112,822 81,825 43,452 J.-L. ROCHON Montreal Maisonneuve- Rosemont 108,023 64,850 42,704 20,595 Hon. J.-P. DESCHATELETSI Ottawa, Ont. Mercier 233,964 120,083 80,904 33,450 P. BOULANGEB Montreal Mont-Royal 128,524 74,982 54,180 37,648 Hon. A. A. MACNAUGHTON Ottawa, Ont. Notre-Dame- de-Grace 100,719 61,237 47,731 30,532 E.-T. ASSELIN Montreal Outremont-Saint-Jean| 63,888 33,945 23,856 13,305 Hon. M. LAMONTAGNE. Ottawa, Ont. Papineau 87,588 48,526 30.605 15,677 Hon. G. FAVBEAU Ottawa, Ont. St. Ann 38,173 19,601 12,989 7,215 G. -

Handbook of Information Relating to the District of Algoma in The

I I r I * ' 1 I I I The EDITH and LORNE PIERCE I COLLECTION of CANADIANA I Queens University at Kingston I . F5^ HANDBOOK OF INFORMATION RELATING TO THE DISTRICT OF ALGOMA IN THE PROVINCE OF ONTARIO. Letters from Settlers and others, and Information as to Land Regulations. Issued under the authority of the Government of Canada (Minister of the Interior). — LAND AVAILABLE FOR SETTLEMENT IN ALGOMA. Tiie district of Algoma forms a part of the province of Ontario, and is situated between Lakes Huron and Superior, the central point in the district being the town of Sault Ste. Marie, which is situated on St. Mary's river, connecting the lakes already mentioned. It contains millions of acres of valuable agricultural and stock-raising lands, and has been receiving considerable attention in the Canadian Press for some time. At the request of the Algoma Land and Colonisation Society, which has been devoting its efforts to attract a desirable class of settlers to the district, the Minister of the Interior in the Dominion G-overnment has authorised the preparation of this pamphlet. It contains, by way of introduction, some particulars as to the vacant lands in Algoma, where and how to obtain them, and gives the names of Government officials who may be communicated with on the subject. As to a description of the district itself, it was thought much better that this should be given by farmers and others who are already settled there, and who could put in their own way the advantages they believed the different parts of the district offered. -

Electoral Districts, Voters on List and Votes Polled, Names and Addresses of Members of the House of Commons, As Elected at the Nineteenth General Election, Mar

PARLIAMENTARY REPRESENTATION 69 9.—Electoral Districts, Voters on List and Votes Polled, Names and Addresses of Members of the House of Commons, as Elected at the Nineteenth General Election, Mar. 26, 1940—continued. Province and Popula Voters Votes Party Electoral District tion, on Polled Name of Member Affili P.O. Address 1931 List ation No. No. No. Quebec—concluded Montreal Island—cone St. Henry 78,127 46,236 31,282 BONNIEK, J. A. Lib. Montreal, Que. St. James 89,374 64,823 35,587 DuROCHER, E. .. Lib. Montreal, Que. St. Lawrence- St. George 40,213 29,416 18,544 CLAXTON, B Lib. Montreal, Que. St. Mary 77,472 49,874 30,289 DESLAURIERS, H1 Lib. Montreal, Que. Verdun 63,144 40,555 28,033 COTE, P. E Lib. Verdun, Que. Ontario— (82 members) Algoma East... 27,925 15,250 10,386 FARQUHAR, T. Lib. Mindemoya, Ont. Algoma West... 35,618 22,454 16,580 NIXON, G. E.. Lib. Sault Ste. Marie, Ont. Brant 21,202 12,980 9,229 WOOD, G. E Lib... Cainsville, Ont. Brantford City.. 32,274 21,607 15,762 MACDONALD, W. R Lib... Brantford, Ont. Bruce 29,842 19,359 12,781 TOMLINSON, W. R Lib... Port Elgin, Ont. Carleton 31,305 20,716 14,481 HYNDMAN, A. B.2 Cons. Carp, Ont. Cochrane 58,284 44,559 26,729 BRADETTE, J. A Lib... Cochrane, Ont. Dufferin-Simcoe. 27,394 19,338 10,840 ROWE, Hon. W. E.... Cons. Newton Robinson, Ont. Durham 25,782 17,095 12,254 RlCKARD, W. F Lib Newcastle, Ont. Elgin 43,436 30,216 20,902 MILLS, W. -

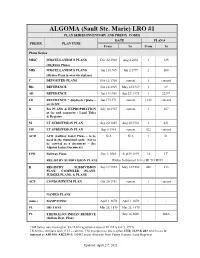

ALGOMA (Sault Ste. Marie) LRO #1 PLAN SERIES INVENTORY and PREFIX CODES DATE PLAN # PREFIX PLAN TYPE from to from to Plans Series

ALGOMA (Sault Ste. Marie) LRO #1 PLAN SERIES INVENTORY AND PREFIX CODES DATE PLAN # PREFIX PLAN TYPE From To From To Plans Series MISC MISCELLANEOUS PLANS Dec 22/1969 Aug 8/2001 1 325 (Highway Plans) MIS MISCELLANEOUS PLANS Jan 11/1965 Jun 2/1999 2 100 (Hydro Plans & oversized plans) C DEPOSITED PLANS Feb 12/1968 current 1 current RD REFERENCE Oct 18/1965 May 12/1969 1 69 AR REFERENCE Jun 19/1959 Jun 23/ 1978 1 2239* 1R REFERENCE * duplicate rplans – Jan 17/1971 current 1133 current see below D BA PLANS & EXPROPRIATION July 18/1967 current 1 107 of fee and easement - Land Titles & Registry M LT SUBDIVISION PLAN Sep 20/1889 Aug 20/1981 1 421 1M LT SUBDIVISION PLAN Sep 3/1981 current 422 current ACR ACR (railway Index Plans – to be N/A N/A 1 51 used in the thumbnail only. Not to be carried as a document – See Algoma Issues Document) CPR Railway Plans Jan 1, 1885 Sept29,1899 1A 1Y REGISTRY SUBDIVISION PLANS Within Instrument Series H1 TO H399 H REGISTRY SUBDIVISION Sep 17/1952 May 12/1982 400 813 PLAN/ COMPILED PLANS, JUDGES PLANS, & PLANS ACP CONDOMINIUM PLAN Oct 20/1981 current 1 current NAMED PLANS (none) BAMPTONS1 April 1 1878 April 1 1878 - - PL HILTON1 Mar 25, 1878 Mar 25, 1878 PL THESSALON INDIAN RESERVE July 16,1889 180A (Indian Dept. Plan) *AR Series runs from rplan. #1-1132 (registration date of #1132 is Jan 5, 1971) 1R Series continues with 1133 – current. The exception to this is rplan 1550, 2239 & 482 which is to be indexed as AR1550 ,AR2239 & AR482 as per direction from Penny Hanson, Land Registrar. -

Chapter I. Legislative Assembly

70 CHAPTER I. LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. SPEAKER—Hos. THOS. BALLAXTYNE. CLERK—CHAS. CLARKE. Constituencies. Representatives. Constituencies. Representatives. Middlesex N R Algoma, East... Alexander E. Campbell. Middlesex', W.R. Hon. Geo. W. Ross. Algoma, West.. James Conmee. Monck Hon. Richard Harcourt. Brant, N.R William B. Wood. Muskoka George F. Marter. Brant, S. R Hon. Arthur S. Hardy. Brockville Hon. Chris. F. Fraser. Norfolk, S.R.... William A. Charlton. Bruce, N.R John George. Norfolk, N.R... E. Carpenter. Bruce, S.R Hamilton P. O'Connor. Northumberland Bruce, C. R Walter McM. Dack. E.R Dr. Willoughby. Cardwell William H. Hammell. Northumberland Carleton Geo. Wm. Monk. W.R Corelli C. Field. Cornwall and Ontario, N.R.... James Glendining. Stormont... William Mack. Ontario, S.R Hon. John Dryden. John Barr. Dundas J. P. Whitney. Oxford, N.R.... Hon. Sir Oliver Mowat. Durham, E.R... George Campbell. Oxford, S.R.... Angus McKay. Durham W.R.. William T. Lockhart. Parry Sound.... James Sharpe. Elgin, E.R Henry T. Godwin. Peel John Smith. Elgin, W.R Dugald MoColl. Perth, N.R Thomas Magvvood. Essex, N.R Sol. White. Perth, S.R Hon. Thos. Ballantyne. Essex, S.R... William D. Balfour. Peterborough, Frontenac H. Smith. E.R Thomas Blezard. James Rayside. Peterborough, Orlando Bush. W.R Grey, N.R James Cleland. Prescott Alfred Evanturel. Grey, C.R Joseph Rorke. Prince Edward.. John A. Sprague. Grey, S.R James H. Hunter. Renfrew, S.R... John F. Dowling. Haldimand. ... Hon. Jacob Baxter. Renfrew, N.R.. Arunah Dunlop. William Kerns. Hamilton ...... Hon. John M. Gibson. Simcoe, E.R A. Miscampbell. -

Public Archives of Canada Archives Publiquesw

PUBLIC ARCHIVES OF CANADA ARCHIVES PUBLIQUESW CANADA MANUSCRIPT DIVISION DIVISION DES MANUSCRITS Hon. M.J.W. COLDWELL MG 27, III C 12 Finding Aid 493 / Instrument de recherche 493 Major James William Coldwell Originals, 1926-1969, 57 feet. Major James William Coldwell (1888-1974) was born in England and received his formal education there, emigrating to Canada in7910. Following a career as teacher, principal of a Regina school, alderman on the Regina city council, and President and Secretary of the Canadian Teacher's Federation, Coldwell became an active participant in and leader of various farm and labour organizations which sprang into existence with the alvent of the depression in 1929. He was Provincial leader of the Farmer-Labour Party of Saskatchewan from 1932 to 1935. He was active in the formation and subsequent development of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation as a national party, serving successively as National Secretary 1934 to 1937, National Chairman 1938 to 1942, and National President and Parliamentary Leader of the C.C.F. from 1942 to 1958. He was Member of Parliament for Rosetown-Biggar from 1935 to 1958. Correspondence Files, 1937-1969. 41 feet, vols. 1-56. These files are mainly nominal files, although there are some subject files as well. They are arranged alphabetically. Subject Files, 1926-1968. 4 feet, vols. 57-62. Major topics within these files include the history and organization of the C.C.F. and the New Democratic Party, and subjects of personal concern to Mr. Coldwell. Speeches, Addresses, Press Releases, Radio Broadcasts, 1933-1966. 9 feet, vols. 62-76. -

Constitttlion and GOVERNMENT. LEGISLATIVE

CONSTITtTlION AND GOVERNMENT. LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. SPEAKER—HON. JACOB BAXTER. CLERK—CHAS. T. GILLMCR. Constituencies Representatives. Constituencies. Representatives. Addington— John Stewart Miller. Middlesex, N.R.. John Waters. Algoma East. Robert Adam Lyon. Middlesex, W R.. Hon. George W. Ross. Algoma West.... James Conmee. Monck Richard Harcourt. Brant, N.R William B. Wood. Muskoka George F. Marter. Brant, S.R Hon. Arthur S. Hardy Norfolk, S.R William Morgan. Brockville Hon. Chris. F. Fraser. Norfolk, N.R John B. Freeman. Bruce, N.R Tohn W. S. Biggar. Northumberland Bruce, S R , Hamilton P. O'Connor E.R Bruce, C.R Walter McM. Dack. Northumberland Cardwell William H. Hammell. W.R Corelli C. Field. Carleton George Wm. Monk. Ontario, N R Isaac J. Gould. Cornwall and Ontario, S.R John Dryden. Stormont William Mack. Ottawa Erskine H. Bronson. Dufferin Falkner C. Stewart. Oxford, N.R Hon. Oliver Mowat. Dundas Oxford. S.R Angus McKay. Durham, E.R Thomas D. Craig. Parry Sound Samuel Armstrong. Durham, W.R.... James W. McLaughlin Peel Kenneth Chisholm. Elgin, E.R Thomas M Nairn. Perth, NT.R George Hess. Elgin, W.R Andrew B. Ingram. Perth, S.R Thomas Ballantyne. Essex, N.R Gaspard Pacaud. Peterborough, Essex, S.R William D. Balfour. E.R Thomas Blezard. Frontenac Henry Wilinot. Peterborough, Glengarry James Rayside. W.R James R. Stratton. Grenville Frederick J. French. Prescott Alfred Evanturel. Grey, N.R David Greighton. Prince Edward... John A. Sprague. Grey, C.R Joseph Rorke Rentrew, S.R.... John A. McAndrew. Grey, S.R John Blyth Renfrew, N.R Thomas Murray. Haldimand Hou. -

Parliamentary Representation 85 9

PARLIAMENTARY REPRESENTATION 85 9.—Population of Electoral Districts, Voters on Lists and Votes Polled, Names and Addresses of Members of the House of Commons, as Elected at the Seventeenth General Election—continued. Province and Popula Voters Votes Electoral District. tion, on Name of Member. P.O. Address. 1931. List. Polled. Quebec—concluded. Hull 49,196 22,790 18,586 Fournier, A.... Hull, Que. Joliette 27,585 12,721 10,964 Ferland, C. E. Joliette, Que. Kamouraska 24,085 10,790 8,713 Bouchard, G.. Ste-Anne-de-la- Poeatiere, Que. Labelle 36,953 Bourassa, H... Outremont, Que. Lake St. John. 50,253 19,181 16,694 Duguay, J. L.. St-Joseph-d'Alma, Que. Laprairie- Napier ville 21,091 9,152 8,345 Dupuis, V Laprairie, Que. L'Assomption-Montcalm.. 29,188 14,061 11,299 Seguin, P. A L'Assomption, Que. Laval-Two Mountains 30,434 13,733 12,345 Sauve, Hon. A Saint-Eustache, Que. Levis 35,656 16,677 14,074 Fortin.E Levis, Que. L'Islet 19,404 8,535 6,804 Fafard, J. F L'Islet, Que. Lotbiniere 23,034 10,381 8,989 Verville, J. A St. Flavien, Que. Matane 45,272 18,249 14,805 LaRue, J. E.H... Amqui, Que. Megantic 35,492 15,889 13,461 Roberge, E Laurierville, Que. Montmagny 20,239 9,405 7,550 Lavergne, A Quebec, Que. Nicolet 28,673 13,680 11,487 Dubois, L Gentilly, Que. Pontiac 64,155 29,732 21,918 Belec, C Fort Coulonge, Que. Portneuf 39,522 18,418 15,175 Desrochers, J St-Raymond, Que.