The Cases of Georg Waitz, Gabriel Monod and Henri Pirenne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michelet Et L'architecture Gothique

Michelet et l'architecture gothique Autor(en): Pommier, Jean Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Études de Lettres : revue de la Faculté des lettres de l'Université de Lausanne Band (Jahr): 26 (1954-1956) Heft 1 PDF erstellt am: 08.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-869934 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch MICHELET ET L'ARCHITECTURE GOTHIQUE Ce n'est pas sans émotion que je prends la parole au sein d'une Université à laquelle je suis attaché par un lien personnel, et dans une cérémonie où nous ne voyons plus parmi nous, sinon par la vivacité du souvenir, celui-là même à l'initiative de qui je dois en premier lieu l'honneur qui m'a été fait il y a six ans, le maître éminent dont nous venons d'entendre le si juste éloge, mon très cher et très regretté compatriote, collègue et ami, René Bray. -

Notes and News

NOTES AND NEWS Dr. Robert Fruin, the doyen of Dutch historical professors, died at Leyden on January 29 (or 30), aged seventy-five. From 1860 until his retirement, a few years ago, he was professor of Dutch history at Ley den. Though he published no great work after the issue of his impor tant TienJaren uit den Tachtigiarigen Oorlog, in 1859, he wrote a large number of important monographs, was the teacher of many if not most of the Dutch historians of the present time, and won unmeasured influ ence by his learning, wisdom and fairness. Professor Alphons Huber of the University of Vienna, author of a highly valued but now unfinished history of Austria in five volumes, and of sevt!ral studies in medieval numismatics, died in Vienna on Novem ber 23, aged 64. Dr. Gustav Gilbert, professor in the gymnasium at Gotha and author of the well-known Handbuch der griechischm Staatsaltertlll'imer, died on December 24. Mr. Edward G. Mason, formerly president of the Chicago Historical Society, died on December IS, at the age of 59. An eminent lawyer and a good citizen, his title to remembrance among historical students rests partly upon his active exertions in behalf of the society mentioned, especially in securing for it its present impressive building and a large portion of its valuable collections, and partly upon those minor writings for which alone his professional occupations left him leisure. The papers which he wrote were chiefly essays in the history of Illinois in the eigh teenth century. Lewis H. Boutell died at Washington, D. -

Dissertacao Clayton F E F Borges.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE HISTÓRIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA CLAYTON FERREIRA E FERREIRA BORGES REVUE HISTORIQUE E REVUE DE SYNTHÈSE HISTORIQUE: O CASO A. D. XÉNOPOL GOIÂNIA 2013 1 TERMO DE CIÊNCIA E DE AUTORIZAÇÃO PARA DISPONIBILIZAR AS TESES E DISSERTAÇÕES ELETRÔNICAS (TEDE) NA BIBLIOTECA DIGITAL DA UFG Na qualidade de titular dos direitos de autor, autorizo a Universidade Federal de Goiás (UFG) a disponibilizar, gratuitamente, por meio da Biblioteca Digital de Teses e Dissertações (BDTD/UFG), sem ressarcimento dos direitos autorais, de acordo com a Lei nº 9610/98, o documento conforme permissões assinaladas abaixo, para fins de leitura, impressão e/ou download, a título de divulgação da produção científica brasileira, a partir desta data. 1. Identificação do material bibliográfico: [ X ] Dissertação [ ] Tese 2. Identificação da Tese ou Dissertação Autor (a): Clayton Ferreira e Ferreira Borges E-mail: [email protected] Seu e-mail pode ser disponibilizado na página? [ X ]Sim [ ] Não Vínculo empregatício do autor Nenhum Agência de fomento: Programa de Reestruturação das Universidades S R Federais Sigla: REUNI País: Brasil UF:GO 024703001C -50 CNPJ: Título: Revue Historique e Revue de Synthèse Historique: o caso A. D. Xénopol Palavras-chave: Xénopol; Revue Historique; Revue de Synthèse Historique; História; ciência Título em outra língua: Revue Historique and Revue de Synthèse Historique: the case A. D. Xénopol Palavras-chave em outra língua: Xénopol, Revue Historique, Synthèse Revue Historique, history, science Área de concentração: Culturas, Fronteiras e Identidades. Data defesa: (26/08/2013) Programa de Pós-Graduação: Programa de Pós-Graduação em História Orientador (a): Cristiano Alencar Arrais E-mail: [email protected] Co-orientador (a):* E-mail: *Necessita do CPF quando não constar no SisPG 3. -

« Notre Siècle Est Le Siècle D'histoire » (Gabriel Monod)

Les racines de l’intérêt pour l’Histoire au XIXe siècle: la Révolution, le Romantisme, le Nationalisme « Notre siècle est le siècle d’Histoire » (Gabriel Monod) I. La Révolution française et son héritage • « Passe maintenant, lecteur ; franchis le fleuve de sang qui sépare à jamais le vieux monde dont tu sors, du monde nouveau à l'entrée duquel tu mourras. » (René de Chateubriand : Mémoires d’Outre-tombe.) • « De mémoire d’historien, jamais peuple n’a éprouvé, dans ses mœurs et dans ses plaisirs, de changement plus rapide et plus total que celui de 1780 à 1823. » (Stendhal, Racine et Shakespeare) • « Le dix-neuvième siècle a une mère auguste, la Révolution française. Il a ce sang énorme dans les veines. (…) La Révolution, toute la Révolution, voilà la source de la littérature du XIXe siècle. » (Victor Hugo : Wiliam Shakespeare) • La Révolution comme une expérience historique: « Car il n’est personne parmi nous, hommes du dix-neuvième siècle, qui n’en sache plus que Velly ou Mable, plus que Voltaire lui-même sur les rébellions et les conquêtes, le démembrement des empires, la chute et la restauration des dynasties, les révolutions démocratiques et les réactions en sens contraire. » (Augustin Thierry: Lettres sur l’histoire de France, préface) II. Romantisme comme un style et comme une sensibilité • « Le Romanticisme est l’art de présenter aux peuples les œuvres littéraires qui, dans l’état actuel de leurs habitudes et de leurs croyances, sont susceptibles de leur donner le plus de plaisir possible. Le classicisme, au contraire, leur présente la littérature qui donnait le plus grand plaisir possible à leurs arrière-grands-pères. -

Rémi Fabre, Francis De Pressensé Et La Défense Des Droits De L'homme

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenEdition Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l’Ouest Anjou. Maine. Poitou-Charente. Touraine 113-2 | 2006 Varia Rémi Fabre, Francis de Pressensé et la défense des Droits de l’Homme. Un intellectuel au combat Christian Bougeard Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/abpo/882 ISBN : 978-2-7535-1502-4 ISSN : 2108-6443 Éditeur Presses universitaires de Rennes Édition imprimée Date de publication : 30 juin 2006 Pagination : 211-217 ISBN : 978-2-7535-0331-1 ISSN : 0399-0826 Référence électronique Christian Bougeard, « Rémi Fabre, Francis de Pressensé et la défense des Droits de l’Homme. Un intellectuel au combat », Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l’Ouest [En ligne], 113-2 | 2006, mis en ligne le 30 juin 2008, consulté le 21 avril 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/abpo/882 © Presses universitaires de Rennes Comptes rendus diant, soulignant que cette lacune s’explique par le manque de recherche sur ce thème, dans l’Ouest de la France. Le livre s’articule en trois parties. Dans la première, intitulée les Héritages, on trouve des communications du regretté Pierre Foucault, de Marie Thérèse Cloître, d’Emmanuel Poisson et de Marie-Véronique Malphettes-Salaün. La seconde partie est consacrée à l’action catholique spécialisée. Les militants du monde rural font l’objet des interventions de Yohann Abiven et Eugène Calvez, le développement du syndicalisme de 1945 à 1970, de celle de Jacqueline Sainclivier, les militants du MFR en Maine et Loire de Jean Luc Marais. -

JULES MICHELET and ROMANTIC HISTORIOGRAPHY by Lionel

1 JULES MICHELET AND ROMANTIC HISTORIOGRAPHY By Lionel Gossman ... a fine book I would like to write: An Appeal to My Contemporaries. The idea would be to show the ultras that there is something worthwhile in the ideas of the liberals, and vice versa. ... If it were written ... in a spirit of charity toward both sides and were widely distributed, such a book might well do some good. ... If I had the talent I would like to write inexpensive books for the people. (Michelet, Journal, June 1820, P. Viallanex and C. Digeon, eds.) In this Chair of Ethics and History ... I had taken up the issue of the times: social and moral unity; pacifying to the best of my ability the class war that eats at us with dull persistence, removing the barriers, more apparent than real, that divide and make enemies of each other classes whose interests are not fundamentally opposed. (Letter to Jean Letronne, Director of the Collège de France, January 1848) This house is old; it knows a lot, touched up and whitewashed to look new as it may be. Centuries have lived in it and each one has left something of itself. Whether you perceive them or not, the traces are there, never doubt it for a moment. Just as in a human heart! Humans and houses, we all bear the imprint of ages past. As young men, we carry within us innumerable ancient notions and feelings of whose presence we are unaware. These traces of ancient times are mixed up inside us, indistinct, often inopportune. -

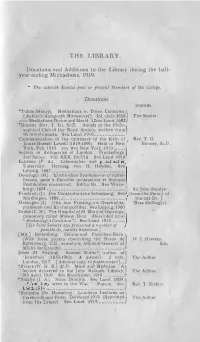

Library 1920S

72 Our Chronic!�. the Mission, as it was and is, who knew little or nothing of it before : he was helped in his task by Mr J. M. Gaussen, an old friend and supporter of the Mission, and by others, who lent their rooms. We are sure that, as a consequence of his THE LIBRARY. stay, interest is reviving, and the gap which the war made has begun to close. We can only echo Mr Janvrin's appeal to all who can to go to Walworth and see the Mission them- Donations and Additions to the Library during the half selves. year ending Michaelmas, 1919. * The asterisk denotes past or presCIIt lllembers of the College. AoAMS MEMORIAL PRIZE. Third Year. The Prize is divided between W. H. M. Donations. Greaves and D. Bhansali. DONORS. First and Second Year. Prizes are awarded to H. W. *Tubbe (Henry). Meditations in Three Centuries.} Swift, D. P. Dalzell, F, B. Baker, aeq. [Author's Autograph Matwscript]. fol. circa 1650 The Master. --Meditations Divine and Moral. 12mo Lond. 1682 } *Bonney (Rev. T. G.), Sc.D. Annals of the Philo- ENGLISH EssAY PRIZES. sophical Club of the Royal Socit::ly, written from its minute books. 8vo Lond. 1919.......... ........... Third Year - G. W.Silk Commemoration of the centenary of the birth of Rev. T. G. James Russell Lowell (1819-1891). Held in New Bonney, Sc.D. S�co11d Year - Not awarded York, Feb. 1919. roy. 8vo New York, 1919 .... , ... First Year E. L. Davison Society of Antiquaries of London. Proceedings. 2nd Series. Vol. XXX. 1917/18. 8vo Lond. -

A Grande Missão E O Verdadeiro Amor Do Século XIX: a Escrita Da História De Ernest Renan (1848-1863) THIAGO AUGUSTO MODESTO R

A grande missão e o verdadeiro amor do século XIX: a escrita da história de Ernest Renan (1848-1863) THIAGO AUGUSTO MODESTO RUDI* Defendemo-nos ainda, afinal de contas, contra a psicologia do tipo daquela de Sainte-Beuve e de Renan, contra esta maneira de espionar e de farejar as almas praticada por estes gozadores afeminados do espírito e desprovidos de espinha dorsal: nos parece indecente vê-los apalpar com os seus dedos curiosos os segredos dos homens e das épocas que foram sob todos os pontos de vista mais elevados, mais severos, mais profundos e mais nobres do que eles; pois estas épocas não teriam facilmente aberto as suas portas a qualquer vagabundo do sexo ambíguo. Mas este século XIX, que perdeu qualquer sentido mais delicado da hierarquia, não sabe mais bater nos dedos dos intrusos, dos indesejáveis, dos assaltantes; pelo contrário, ele fica orgulhoso com o seu “espírito historiador”, graças ao qual é permitido ao plebeu esforçado, contanto que carregue os seus instrumentos de tortura e as suas folhas de pesquisa, introduzir-se na sociedade por mais fechada que seja, entre os santos da consciência moral e também entre os mestres eternamente velados do espírito (NIETZSCHE, 2005:341-342). Em 1885, ao denunciar o característico “espírito historiador” do século XIX, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) contribuía para a repetida inserção de Ernest Renan (1823-1892) no rol dos grandes nomes da historiografia oitocentista. Renan, um dos “plebeus esforçados”, possuía os requisitos basilares para o posto de “bufão”: carregar várias folhas de pesquisa, espionar, farejar, apalpar e penetrar com dedos curiosos os segredos de épocas passadas1. -

1 This Is a Pre-Copy-Editing, Author-Produced PDF of an Article

This is a pre-copy-editing, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in The Historical Journal following peer review. The definitive publisher-authenticated version will be available online at: http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayJournal?jid=HIS Historiographical Review ERNEST RENAN’S RACE PROBLEM* ROBERT D. PRIEST Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge Abstract This essay revisits the role of race in Ernest Renan’s thought by situating contemporary debates in a long perspective that extends back to his texts and their earliest interpreters. Renan is an ambivalent figure: from the 1850s onwards he used ‘race’ to denote firm differences between the ‘Aryan’ and ‘Semitic’ language groups in history; but after 1870 he repeatedly condemned biological racism in various venues and contexts. I show that the tension between these two sides of Renan’s thought has continually resurfaced in criticism and historiography ever since the late nineteenth century. Renan’s racial views have been subject to particularly close scrutiny following Léon Poliakov and Edward Said’s critiques in the 1970s, but the ensuing debate risks developing into an inconclusive tug-of-war between attack and apologia. I propose three fresh directions for research. Firstly, historians should situate the evolution of Renan’s ideas on race in closer biographical context; secondly, they must reconsider the cultural authority of his texts, which is often more asserted than proven; thirdly, they should pay greater attention to his reception outside Europe, particularly regarding his writing on Islam. 1 I would like to distinguish between the Renan of legend and the Renan of reality. -

Revista Trilhas Da História. Três Lagoas, V.8, Nº16, Jan-Jul, 2019. P.119-139 ISSN:2238-1651 120

119 A historiografia francesa do século XIX nas páginas da Revue Historique (1876- 1914)1 BORGES, Clayton Ferreira e Ferreira2 Resumo: O presente artigo tem por objetivo analisar a Revue Historique por meio de um mapeamento de ordem quantitativa da produção historiográfica publicada no periódico entre os anos de 1876-1914. Deste ponto de partida realizamos uma breve análise qualitativa sobre os dados levantados, com vistas a contextualizar a conjuntura intelectual que subsumiu o historicismo francês, especificamente no que se refere à – genericamente – conhecida Escola Metódica. Assim como procura jogar luz sobre a importância desta geração de intelectuais no interior do processo de constituição epistemológica e institucionalização acadêmica da história na França durante a segunda metade do século XIX, para além dos mitos historiográficos produzidos pela escola dos annales, tautologicamente reproduzidos na tradição historiográfica brasileira. Palavras-chave: Revue Historique; Escola Metódica; Historiografia francesa. A nineteenth-century French historiography in the pages of the Historical Review (1876-1914) Abstract: The purpose of this article is to analyze the Revue Historique by means of a quantitative mapping of historiographical production published in the periodical period between 1876 and 1914. From this starting point we make a brief qualitative analysis on the data collected, with a view to contextualizing the intellectual conjuncture that subsumed French historicism, specifically with regard to the – generically – known Methodical School. Just as it seeks to throw light on the importance of this generation of intellectuals within the process of epistemological constitution and academic institutionalization of history in France during the second half of the nineteenth century, in addition to the historiographical myths produced by the school of the annales, tautologicamente reproduced in the historiographical tradition Brazilian Keywords: Revue Historique; Methodical school; French Historiography. -

Rolandbarthestext:Pchamoiseau Pages

Roland Barthes at the Collège de France Contemporary French and Francophone Cultures 22 Contemporary French and Francophone Cultures Series Editors EDMUND SMYTH CHARLES FORSDICK Manchester Metropolitan University University of Liverpool Editorial Board JACQUELINE DUTTON LYNN A. HIGGINS MIREILLE ROSELLO University of Melbourne Dartmouth College University of Amsterdam MICHAEL SHERINGHAM DAVID WALKER University of Oxford University of Sheffield This series aims to provide a forum for new research on modern and contem- porary French and francophone cultures and writing. The books published in Contemporary French and Francophone Cultures reflect a wide variety of critical practices and theoretical approaches, in harmony with the intellectual, cultural and social developments which have taken place over the past few decades. All manifestations of contemporary French and francophone culture and expression are considered, including literature, cinema, popular culture, theory. The volumes in the series will participate in the wider debate on key aspects of contemporary culture. Recent titles in the series: 6 Jane Hiddleston, Assia Djebar: Out 14 Andy Stafford, Photo-texts: of Africa Contemporary French Writing of 7 Martin Munro, Exile and Post- the Photographic Image 1946 Haitian Literature: Alexis, 15 Kaiama L. Glover, Haiti Unbound: Depestre, Ollivier, Laferrière, A Spiralist Challenge to the Danticat Postcolonial Canon 8 Maeve McCusker, Patrick 16 David Scott, Poetics of the Poster: Chamoiseau: Recovering Memory The Rhetoric of Image-Text 9 Bill Marshall, The French Atlantic: 17 Mark McKinney, The Colonial Travels in Culture and History Heritage of French Comics 10 Celia Britton, The Sense of 18 Jean Duffy, Thresholds of Meaning: Community in French Caribbean Passage, Ritual and Liminality in Fiction Contemporary French Narrative 11 Aedín Ní Loingsigh, Postcolonial 19 David H. -

La Place De La Science Allemande Dans Deux Revues D'histoire, La

Diplôme de conservateur de bibliothèque La place de la science allemande dans deux revues d’histoire, la Revue historique et la Revue de synthèse historique RAPPORT D’ETAPE – JANVIER 2006 Cécile Boillot Sous la direction de Michel Espagne Directeur de recherche, Paris 8 Remerciements Mes remerciements vont en premier lieu à mon directeur de thèse, Michel Espagne, qui manifeste pour mon travail un intérêt constant et qui encourage mes recherches. Je tiens ensuite à remercier chaleureusement mes colocataires pour leur soutien moral et logistique. Enfin, j’adresse un merci particulier à mon relecteur habituel, dont les commentaires et remarques sont d’une grande aide. BOILLOT Cécile | DCB 15 | Rapport d’étape | janvier 2006 2 Droits d’auteur réservés. Résumé : La présente étude porte sur la place de l’Allemagne dans deux revues d’histoire, la Revue historique et la Revue de synthèse historique, publiées, la première à partir de 1876, la seconde de 1900. Elle retrace leur histoire et s’intéresse à la personnalité leurs fondateurs respectifs, Gabriel Monod et Henri Berr, plus particulièrement à leurs relations avec l’Allemagne. Elle compare enfin la place occupée par les ouvrages allemands dans chacune des deux revues. Ainsi, par le biais de ces revues savantes, il est ainsi possible d’évaluer l’influence exercée par la science allemande sur l’historiographie française. Descripteurs : Revue de synthèse historique (périodique) - - Histoire Revue historique (histoire) - - Histoire Monod, Gabriel (1844-1912) Berr, Henri (1863-1954) Historiographie - - France - - Influence allemande - - XIXe siècle Historiographie - - France - - Influence allemande - - XXe siècle Toute reproduction sans accord exprès de l’auteur à des fins autres que strictement personnelles est prohibée.