JULES MICHELET and ROMANTIC HISTORIOGRAPHY by Lionel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michelet and Natural History: the Alibi of Nature1

Michelet and Natural History: The Alibi of Nature1 LIONEL GOSSMAN Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures Princeton University In Honor of Per Nykrog The hard-working molluscs make up an interesting, modest people of poor, little workers, whose laborious way of life constitutes the seri- ous charm and the morality of the sea. Here all is friendly. These little creatures do not speak to the world, but they work for it. They leave it to their sublime father, the Ocean, to speak for them. He speaks in their place and they have their say through his great voice. (Michelet, La Mer 1.iii)2 I had come to look on the whole of natural history as a branch of the political. All the living species, each in its humble right, came knock- ing at the door and claiming admittance to the bosom of Democracy. Why should their more advanced brothers refuse the protection of law to those to whom the universal Father has given a place in the harmony of the law of the universe? Such was the source of my renewal, the belated vita nuova which led me little by little to the nat- ural sciences. (Michelet, L’Oiseau, Introduction)3 1 This text replaces that which was published in 1999 by Editions Rodopi, B.V., Amsterdam (Netherlands) in a volume entitled The World and its Rival: Essays on Literary Imagination in Honor of Per Nykrog. 2 “Peuple intéressant, modeste, des mollusques travailleurs, pauvres petits ouvriers dont la vie laborieuse fait le charme sérieux, la moralité de la mer. -

The Historian As Novelist

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Bryn Mawr College Publications, Special Emeritus Papers Collections, Digitized Books 2001 The iH storian as Novelist John Salmon Bryn Mawr College Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/emeritus Recommended Citation Salmon, John, "The iH storian as Novelist" (2001). Emeritus Papers. 7. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/emeritus/7 This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/emeritus/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Historian as Novelist John Salmon Delivered March 1, 2001 To start with, let me say that the title of the novel that is the subject of this talk is misleading. It reads: "The Muskets of Gascony: The Revolt of Bernard d'Audijos by Armand Daudeyos, translated by J. H. M. Salmon." This is false. When you write a historical novel things do seem to become falsified at times. I am the actual author, and Armand Daudeyos, the supposed descendant of the hero (Daudeyos is the Gascon form of d'Audijos) is a faction. I adopted this device for several reasons. First, it adds an air of mystery to pretend that one has discovered the manuscript of a historical novel based on real events in the seventeenth century and written in the Romantic vogue of the nineteenth century. Second, it allows me to insert a "translator's preface" explaining how close the book is to what actually happened. And third, it protects me from the reproaches of my colleagues for betraying my profession. -

Michelet Et L'architecture Gothique

Michelet et l'architecture gothique Autor(en): Pommier, Jean Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Études de Lettres : revue de la Faculté des lettres de l'Université de Lausanne Band (Jahr): 26 (1954-1956) Heft 1 PDF erstellt am: 08.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-869934 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch MICHELET ET L'ARCHITECTURE GOTHIQUE Ce n'est pas sans émotion que je prends la parole au sein d'une Université à laquelle je suis attaché par un lien personnel, et dans une cérémonie où nous ne voyons plus parmi nous, sinon par la vivacité du souvenir, celui-là même à l'initiative de qui je dois en premier lieu l'honneur qui m'a été fait il y a six ans, le maître éminent dont nous venons d'entendre le si juste éloge, mon très cher et très regretté compatriote, collègue et ami, René Bray. -

Notes and News

NOTES AND NEWS Dr. Robert Fruin, the doyen of Dutch historical professors, died at Leyden on January 29 (or 30), aged seventy-five. From 1860 until his retirement, a few years ago, he was professor of Dutch history at Ley den. Though he published no great work after the issue of his impor tant TienJaren uit den Tachtigiarigen Oorlog, in 1859, he wrote a large number of important monographs, was the teacher of many if not most of the Dutch historians of the present time, and won unmeasured influ ence by his learning, wisdom and fairness. Professor Alphons Huber of the University of Vienna, author of a highly valued but now unfinished history of Austria in five volumes, and of sevt!ral studies in medieval numismatics, died in Vienna on Novem ber 23, aged 64. Dr. Gustav Gilbert, professor in the gymnasium at Gotha and author of the well-known Handbuch der griechischm Staatsaltertlll'imer, died on December 24. Mr. Edward G. Mason, formerly president of the Chicago Historical Society, died on December IS, at the age of 59. An eminent lawyer and a good citizen, his title to remembrance among historical students rests partly upon his active exertions in behalf of the society mentioned, especially in securing for it its present impressive building and a large portion of its valuable collections, and partly upon those minor writings for which alone his professional occupations left him leisure. The papers which he wrote were chiefly essays in the history of Illinois in the eigh teenth century. Lewis H. Boutell died at Washington, D. -

Dissertacao Clayton F E F Borges.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE HISTÓRIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA CLAYTON FERREIRA E FERREIRA BORGES REVUE HISTORIQUE E REVUE DE SYNTHÈSE HISTORIQUE: O CASO A. D. XÉNOPOL GOIÂNIA 2013 1 TERMO DE CIÊNCIA E DE AUTORIZAÇÃO PARA DISPONIBILIZAR AS TESES E DISSERTAÇÕES ELETRÔNICAS (TEDE) NA BIBLIOTECA DIGITAL DA UFG Na qualidade de titular dos direitos de autor, autorizo a Universidade Federal de Goiás (UFG) a disponibilizar, gratuitamente, por meio da Biblioteca Digital de Teses e Dissertações (BDTD/UFG), sem ressarcimento dos direitos autorais, de acordo com a Lei nº 9610/98, o documento conforme permissões assinaladas abaixo, para fins de leitura, impressão e/ou download, a título de divulgação da produção científica brasileira, a partir desta data. 1. Identificação do material bibliográfico: [ X ] Dissertação [ ] Tese 2. Identificação da Tese ou Dissertação Autor (a): Clayton Ferreira e Ferreira Borges E-mail: [email protected] Seu e-mail pode ser disponibilizado na página? [ X ]Sim [ ] Não Vínculo empregatício do autor Nenhum Agência de fomento: Programa de Reestruturação das Universidades S R Federais Sigla: REUNI País: Brasil UF:GO 024703001C -50 CNPJ: Título: Revue Historique e Revue de Synthèse Historique: o caso A. D. Xénopol Palavras-chave: Xénopol; Revue Historique; Revue de Synthèse Historique; História; ciência Título em outra língua: Revue Historique and Revue de Synthèse Historique: the case A. D. Xénopol Palavras-chave em outra língua: Xénopol, Revue Historique, Synthèse Revue Historique, history, science Área de concentração: Culturas, Fronteiras e Identidades. Data defesa: (26/08/2013) Programa de Pós-Graduação: Programa de Pós-Graduação em História Orientador (a): Cristiano Alencar Arrais E-mail: [email protected] Co-orientador (a):* E-mail: *Necessita do CPF quando não constar no SisPG 3. -

French Historians in the Nineteenth Century

French Historians in the Nineteenth Century French Historians in the Nineteenth Century: Providence and History By F.L. van Holthoon French Historians in the Nineteenth Century: Providence and History By F.L. van Holthoon This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by F.L. van Holthoon All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3409-X ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3409-4 To: Francisca van Holthoon-Richards TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...................................................................................... ix Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction Part 1 Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 10 Under the Wings of Doctrinaire Liberalism Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 12 Germaine de Staël on Napoleon Chapter Four .............................................................................................. 23 Le Moment Guizot, François Guizot Chapter Five ............................................................................................. -

« Notre Siècle Est Le Siècle D'histoire » (Gabriel Monod)

Les racines de l’intérêt pour l’Histoire au XIXe siècle: la Révolution, le Romantisme, le Nationalisme « Notre siècle est le siècle d’Histoire » (Gabriel Monod) I. La Révolution française et son héritage • « Passe maintenant, lecteur ; franchis le fleuve de sang qui sépare à jamais le vieux monde dont tu sors, du monde nouveau à l'entrée duquel tu mourras. » (René de Chateubriand : Mémoires d’Outre-tombe.) • « De mémoire d’historien, jamais peuple n’a éprouvé, dans ses mœurs et dans ses plaisirs, de changement plus rapide et plus total que celui de 1780 à 1823. » (Stendhal, Racine et Shakespeare) • « Le dix-neuvième siècle a une mère auguste, la Révolution française. Il a ce sang énorme dans les veines. (…) La Révolution, toute la Révolution, voilà la source de la littérature du XIXe siècle. » (Victor Hugo : Wiliam Shakespeare) • La Révolution comme une expérience historique: « Car il n’est personne parmi nous, hommes du dix-neuvième siècle, qui n’en sache plus que Velly ou Mable, plus que Voltaire lui-même sur les rébellions et les conquêtes, le démembrement des empires, la chute et la restauration des dynasties, les révolutions démocratiques et les réactions en sens contraire. » (Augustin Thierry: Lettres sur l’histoire de France, préface) II. Romantisme comme un style et comme une sensibilité • « Le Romanticisme est l’art de présenter aux peuples les œuvres littéraires qui, dans l’état actuel de leurs habitudes et de leurs croyances, sont susceptibles de leur donner le plus de plaisir possible. Le classicisme, au contraire, leur présente la littérature qui donnait le plus grand plaisir possible à leurs arrière-grands-pères. -

Rémi Fabre, Francis De Pressensé Et La Défense Des Droits De L'homme

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenEdition Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l’Ouest Anjou. Maine. Poitou-Charente. Touraine 113-2 | 2006 Varia Rémi Fabre, Francis de Pressensé et la défense des Droits de l’Homme. Un intellectuel au combat Christian Bougeard Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/abpo/882 ISBN : 978-2-7535-1502-4 ISSN : 2108-6443 Éditeur Presses universitaires de Rennes Édition imprimée Date de publication : 30 juin 2006 Pagination : 211-217 ISBN : 978-2-7535-0331-1 ISSN : 0399-0826 Référence électronique Christian Bougeard, « Rémi Fabre, Francis de Pressensé et la défense des Droits de l’Homme. Un intellectuel au combat », Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l’Ouest [En ligne], 113-2 | 2006, mis en ligne le 30 juin 2008, consulté le 21 avril 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/abpo/882 © Presses universitaires de Rennes Comptes rendus diant, soulignant que cette lacune s’explique par le manque de recherche sur ce thème, dans l’Ouest de la France. Le livre s’articule en trois parties. Dans la première, intitulée les Héritages, on trouve des communications du regretté Pierre Foucault, de Marie Thérèse Cloître, d’Emmanuel Poisson et de Marie-Véronique Malphettes-Salaün. La seconde partie est consacrée à l’action catholique spécialisée. Les militants du monde rural font l’objet des interventions de Yohann Abiven et Eugène Calvez, le développement du syndicalisme de 1945 à 1970, de celle de Jacqueline Sainclivier, les militants du MFR en Maine et Loire de Jean Luc Marais. -

Jules Michelet: National History, Biography, Autobiography1

JULES MICHELET: NATIONAL HISTORY, BIOGRAPHY, AUTOBIOGRAPHY1 By Lionel Gossman Echoes of lived experience are to be found in the work of many historians. Writing about the past is usually also, indirectly, a way of writing about the present. The past is read through the present and the present through a vision of the past. It has often been noted, for instance, that the author’s reaction to the world around him is reflected in the work of Jacob Burckhardt, the great nineteenth-century Swiss historian, who was born into one of the leading patrician families of the old free city of Basel at a moment when these merchant families, rulers of the little city-state since the Renaissance, were coming under increasingly uncomfortable pressure from the political movements of the time. As examples of such reflections of personal experience one could cite Burckhardt’s often severe criticism, in the Griechische Kulturgeschichte, of the ancient Greek polis and in particular of ancient democracy, and his portraits of talented and distinguished citizens who either fled their city after the coming of democratic rule or, like Diogenes and Epicurus, took the path of inner exile. In Burckhardt’s writing, however, the personal experience is not intentional or programmatic. With Michelet, in contrast – whose work, as it happens, Burckhardt knew and admired – history is explicitly presented, in the historian’s reflection on his craft, not only as a form of bio-graphy, of writing about a living being (France), but of auto-bio-graphy, of writing about a living being that is identified as oneself. -

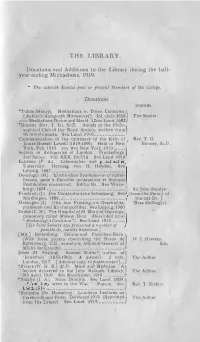

Library 1920S

72 Our Chronic!�. the Mission, as it was and is, who knew little or nothing of it before : he was helped in his task by Mr J. M. Gaussen, an old friend and supporter of the Mission, and by others, who lent their rooms. We are sure that, as a consequence of his THE LIBRARY. stay, interest is reviving, and the gap which the war made has begun to close. We can only echo Mr Janvrin's appeal to all who can to go to Walworth and see the Mission them- Donations and Additions to the Library during the half selves. year ending Michaelmas, 1919. * The asterisk denotes past or presCIIt lllembers of the College. AoAMS MEMORIAL PRIZE. Third Year. The Prize is divided between W. H. M. Donations. Greaves and D. Bhansali. DONORS. First and Second Year. Prizes are awarded to H. W. *Tubbe (Henry). Meditations in Three Centuries.} Swift, D. P. Dalzell, F, B. Baker, aeq. [Author's Autograph Matwscript]. fol. circa 1650 The Master. --Meditations Divine and Moral. 12mo Lond. 1682 } *Bonney (Rev. T. G.), Sc.D. Annals of the Philo- ENGLISH EssAY PRIZES. sophical Club of the Royal Socit::ly, written from its minute books. 8vo Lond. 1919.......... ........... Third Year - G. W.Silk Commemoration of the centenary of the birth of Rev. T. G. James Russell Lowell (1819-1891). Held in New Bonney, Sc.D. S�co11d Year - Not awarded York, Feb. 1919. roy. 8vo New York, 1919 .... , ... First Year E. L. Davison Society of Antiquaries of London. Proceedings. 2nd Series. Vol. XXX. 1917/18. 8vo Lond. -

S.Palmié and C. Stewart (Eds), the Varieties of Historical Experience

Forthcoming in: S.Palmié and C. Stewart (eds), The Varieties of Historical Experience. London: Routledge, 2019. Abstract: In this chapter we map out an interdisciplinary approach to historical experience, understood as the affects and sensations activated when people, in a given present, enter into relationship with the past. In the nineteenth century, professional historiography arose by embracing principles of the scientific method such as rationality, impartiality and a dispassionate approach to research, thereby displacing genres such as poetry, art, and literary fiction that had previously conveyed knowledge of the past in more sublime modes. While the dichotomy between subjective empathy and objective understanding continued to be negotiated within the history profession, in wider society people continued to engage in all manner of sensory relationships with the past including spiritualism, psychometry and occasional bouts of Stendhal Syndrome. Technologies such as photography, phonography, and film provided new media that incited yet richer sensorial and sentimental experiences of the past. With the advent of video games and virtual reality beginning in the the late twentieth century, yet more immediate engagements with the past have proliferated. This essay surveys this variety of historical experiences in Western societies; their social relationship with professional historiography; the present(ist) demand for a personal experience of the past; and the future of historical experience portended by digital technologies. Stephan Palmié and Charles Stewart THE VARIETIES OF HISTORICAL EXPERIENCE In the tale of human passion, in past ages, there is something of interest even in the remoteness of time. We love to feel within us the bond which unites us to the most distant eras, – men, nations, customs perish; THE AFFECTIONS ARE IMMORTAL! – they are the sympathies which unite the ceaseless generations. -

View of Liberal And

Representation, Narrative, and “Truth”: Literary and Historical Epistemology in 19th-Century France Sam Schuman Candidate for Senior Honors in History, Oberlin College Thesis Advisors: Annemarie Sammartino, Leonard Smith Submitted Spring 2021 Schuman 1 Table of Contents Preface and Acknowledgements 2 Introduction 4 Chapter 1: Jules Michelet and the Poetics of History 19 Chapter 2: Honoré de Balzac, The Human Comedy, and the Social Real 34 Chapter 3: Émile Zola, Positivist Realism, and the Novel as Science 53 Conclusion 70 Bibliography 75 Schuman 2 Acknowledgements I would not have been able to complete this project without the immense amount of wisdom, support, and love that I’ve been fortunate to receive from so many people. Any attempt to list all of them would inevitably fail, but better to have something than nothing, no? First, I am grateful to Len Smith and Ari Sammartino for their encouragement, support, and good humor as my advisors on this thesis as well as in the History Department over the last three years. I met Len and Ari in my first and second semesters at Oberlin, respectively, and they have both played a huge role in my intellectual growth by encouraging me to articulate and pursue my own interests and engaging with my ideas with rigor and enthusiasm. Hal Sundt’s literary journalism course was a milestone in my growth as a writer and impressed upon me a lingering obsession with the conceptual difference between facts and truths. Libby Murphy’s course on prostitution in early-19th-century Paris introduced me to a wealth of knowledge and sources that have been invaluable in my own research, and her interdisciplinary method inspired me to reflect critically on my own ways of thinking about the past.