In the Absence of Documentation 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Programme As A

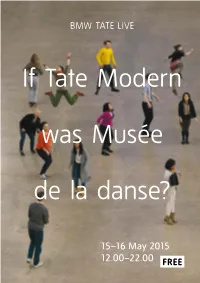

Introduction 15–16 May 2015 12.00–22.00 FREE #dancingmuseum Map Introduction BMW TATE LIVE: If Tate Modern was Musée de la danse? Tate Modern Friday 15 May and Saturday 16 May 2015 12.00–22.00 FREE Starting with a question – If Tate Modern was Musée de la danse? Restaurant – this project proposes a fictional transformation of the art museum 6 via the prism of dance. A major new collaboration between Tate Modern and the Musée de la danse in Rennes, France, directed by Members Room dancer and choreographer Boris Charmatz, this temporary 5 occupation, lasting just 48 hours, extends beyond simply inviting the 20 Dancers discipline of dance into the art museum. Instead it considers how the 4 museum can be transformed by dance altogether as one institution 20 Dancers overlaps with another. By entering the public spaces and galleries of 3 Tate Modern, Musée de la danse dramatises questions about how art might be perceived, displayed and shared from a danced and 20 Dancers expo zéro choreographed perspective. Charmatz likens the scenario to trying on 2 a new pair of glasses with lenses that opens up your perception to River Café forms of found choreography happening everywhere. Entrance 1 Shop Shop Turbine Hall Presentations of Charmatz’s work are interwoven with dance À bras-le-corps 0 to manger 0performances that directly involve viewers. Musée de la danse’s Main regular workshop format, Adrénaline – a dance floor that is open Entrance to everyone – is staged as a temporary nightclub. The Turbine Hall oscillates between dance lesson and performance, set-up and take-down, participation and party. -

Exhibiting Performance Art's History

EXHIBITING PERFORMANCE ART’S HISTORY Harry Weil 100 Years (version #2, ps1, nov 2009), a group show at MoMA PS1, Long Island City, New York, November 1, 2009 –May 3, 2010 and Off the Wall: Part 1—Thirty Performative Actions, a group show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, July 1–September 19, 2010. he past decade has born witness 100 Years, curated by MoMA PS1 cura- to the proliferation of perfor- tor Klaus Biesenbach and art historian mance art in the broadest venues RoseLee Goldberg, structured a strictly Tyet seen, with notable retrospectives of linear history of performance art. A Marina Abramović, Gina Pane, Allan five-inch thick straight blue line ran the Kaprow, and Tino Sehgal held in Europe length of the exhibition, intermittently and North America. Performance has pierced by dates written in large block garnered a space within the museum’s letters. The blue path mimics the simple hallowed halls, as these institutions have red and black lines of Alfred Barr’s chart hurriedly begun collecting performance’s on the development of modern art. Barr, artifacts and documentation. As such, former director of MoMA, created a museums play an integral role in chroni- simple scientific chart for the exhibition cling performance art’s little-detailed Cubism and Abstract Art (1935) that history. 100 Years (version #2, ps1, nov streamlines the genealogy of modern 2009) at MoMA PS1 and Off the Wall: art with no explanatory text, reduc- Part 1—Thirty Performative Actions at ing it to a chronological succession of the Whitney Museum of American avant-garde movements. -

Ari Benjamin Meyers

ARI BENJAMIN MEYERS Born 1972 (New York, USA) Lives and works in Berlin, Germany EDUCATION 1996–1998 Fullbright Grant: Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler, Berlin, Germany, Certificate in Conducting 1994–1996 The Peabody Institue, Baltimore, Maryland, USA, MM Conducting 1990–1994 Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA, BA Composition (Cum Laude) 1990–1997 The Juilliard School Pre-College Division, New York, New York, USA, Composition and Piano SOLO EXHIBITIONS AND PRESENTATIONS 2019 In Concert, OGR – Officine Grandi Riparazioni, Turin, Italy 2018 Kunsthalle for Music, Witte de With, Rotterdam, Netherlands 2017 An exposition, not an exhibition, Spring Workshop, Hong Kong, China Solo for Ayumi, Esther Schipper, Berlin, Germany 2016 The Name Of This Band is The Art, RaebervonStenglin, Zurich, Switzerland 2015 Atlas of Melodies, abc Berlin, Berlin, Germany 2013 Black Thoughts, Esther Schipper, Berlin, Germany Songbook, Esther Schipper, Berlin, Germany SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2016 Musikwerke Bildene Künstler, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, Germany Oscillations, Trafo Center for Contemporary Art, Szczecin, Poland 2015 music, Fahrbereitschaft – Haubrok Collection, Berlin, Germany Artists’ Weekend, Ngorongoro, Berlin, Germany The Verismo Project, Kunst im Kino, Kino International, Berlin, Germany 2014 Supergroup, Tanzhaus NRW, Düsseldorf, Germany I Take Part and the Part Takes Me, Gallery Tanja Wagner, Berlin, Germany The New Empirical, Hatje Cantz & Du Moulin im Bikini, Berlin, Germany 2012 I Wish This Was a Song. Music in Contemporary Art, -

Marian Goodman Gallery

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY TINO SEHGAL Born: London, England, 1976 Lives and works in Berlin Awards: Golden Lion, Venice Biennale, 2013 Shortlist for the Turner Prize, 2013 American International Association of Art Critics: Best Show Involving Digital Media, Video, Film Or Performance, 2011 SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Enoura Observatory, Odawara Art Foundation, Japan Accelerator Stockholms University, Stockholm, Sweden Tino Sehgal, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York 2018 Tino Sehgal, Kunstmuseum Stuttgart, Germany This Success, This Failure, Kunsten, Aalborg, Denmark This You, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C., USA Oficine Grandi Riparazioni, Turin, Italy 2017 Tino Sehgal, Fondation Beyeler, Switzerland V-A-C Live: Tino Sehgal, the New Tretyakov Gallery and the Schusev State Museum of Architecture, Moscow Russia 2016 Carte Blanche to Tino Sehgal, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France Jemaa el-Fna, Marrakesh, Morocco Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Lichthof, Germany Sehgal / Peck / Pite / Forsythe, Opéra de Paris, Palais Garnier, France 2015 A Year at the Stedelijk: Tino Sehgal, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Tino Sehgal, Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin, Germany Tino Sehgal, Helsinki Festival, Finland 2014 This is so contemporary, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney These Associations, CCBB, Centro Cultural Banco de Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil These Associations, Pinacoteca do Estado de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil 2013 Tino Sehgal, Musee d'Art Contemporain de Montreal, Montreal, Canada Tino Sehgal: This Situation, -

Tino Sehgal's

KALDOR PUBLIC ART PROJECT 29: TINO SEHGAL’S THIS IS SO CONTEMPORARY For the 29th Kaldor Public Art Project, internationally acclaimed artist Tino Sehgal presents This is so contemporary, from 6 – 23 February 2014 at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Kaldor Public Art Projects and the Art Gallery of New South Wales have a long-standing relationship, which began with Project 3: Gilbert and George in 1973. This is so contemporary, the third project Kaldor Public Art Projects has presented in the Gallery’s classical vestibule, is spontaneous and contagiously uplifting, directly engaging the Gallery’s visitors. Sehgal has pioneered a radical and captivating way of making art. He orchestrates interpersonal encounters through dance, voice and movement, which have become renowned for their intimacy. This is so contemporary, first presented at the 2005 Venice Biennale and making its Australian debut, is no exception. In 2013, Sehgal was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale, one of the world’s most prestigious art awards, and was shortlisted for the Tate Modern’s Turner Prize. Key recent exhibitions include This Progress at the Guggenheim New York in 2010, These Associations at the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in 2012 and This Variation at dOCUMENTA 13. Sehgal leaves no material traces, creating something that is at once valuable and entirely immaterial in a world already full of objects. His works reside only in the space and time they occupy, and in the memory of the work and its reception. In order to focus all the attention on the physical evidence, the artist does not allow his work to be photographed or illustrated - no documentation or reproduction is permitted. -

PROJECT 27 13 Rooms 2013 13 Rooms 11 – 21 April 2013 Pier 2/3, Walsh Bay, Sydney

PROJECT 27 13 Rooms 2013 13 Rooms 11 – 21 April 2013 Pier 2/3, Walsh Bay, Sydney BIOGRAPHIES HANS ULRICH OBRIST Swiss curator Hans Ulrich Obrist is Co-director of Exhibitions and Programs and Director of International Projects at the Serpentine Gallery, London. He has previously served as curator of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and Museum in Progress, Vienna. KLAUS BIESENBACH Klaus Biesenbach is Director of MoMA PS1 in New York and a Chief Curator at Large at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. He was the Founding Director of both the Kunst- Werke Institute of Contemporary Art in Berlin and the Berlin Biennale. Key international exhibitions organised by Biesenbach include MoMA’s landmark show Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present (2010) and Hybrid Workspace at documenta X (Kassel, 1997 ). EXHIBITING ARTISTS Marina Abramović; John Baldessari; Joan Jonas; Damien Hirst; Tino Sehgal; Allora and Calzadilla; Simon Fujiwara; Xavier Le Roy; Laura Lima; Roman Ondak; Santiago Sierra; Xu Zhen; Clark Beaumont FACTS It’s not called 13 Performances because it’s not 13 performances. It’s not called 13 Artists because that would be irritating. It’s not called 13 Sculptures because that would be misleading. Instead it’s called 13 Rooms. – Klaus Biesenbach Exhibitions are fundamentally a medium of social encounter. – Hans Ulrich Obrist 13 Rooms ran for 11 days at Pier 2/3, Walsh Bay, Sydney. The exhibition was originally commissioned as 11 Rooms by Manchester International Festival, the International Arts Festival RUHRTRIENNALE 2012- 2014 and Manchester Art Gallery. In addition to the 12 international artists selected to participate in the project, Australian artist duo Clark Beaumont were invited by the curators to present work in a new thirteenth room. -

Infinite Experience

March, 2015 For immediate release TEMPORARY EXHIBITION Infinite Experience Curator: Agustín Pérez Rubio Artists: Allora & Calzadilla - Diego Bianchi - Elmgreen & Dragset – Dora García - Pierre Huyghe - Roman Ondák - Tino Sehgal - Judi Werthein Level 2. From March 20 to June 8 Opening: Thursday, March 19 In March will open at MALBA Infinite Experience, an exhibition of live works that incites reflection on forms of life as well as art and the museum, The works featured in an event with no precedent at a museum in Latin America consist of constructed situations, live installations, and representations and choreographies created in the first years of the 21st century. Works by eight outstanding artists from Argentina and abroad will be featured in the exhibition: Allora & Calzadilla [Jennifer Allora (Philadelphia, 1974) and Guillermo Calzadilla (Havana, 1971)], Diego Bianchi (Buenos Aires, 1969), Elmgreen & Dragset [Michael Elmgreen (Copenhagen, 1961) and Ingar Dragset (Trondheim, Norway, 1968)], Dora García (Valladolid, Spain, 1965), Pierre Huyghe (Paris, 1962), Roman Ondák (Žilina, Slovakia, 1966), Tino Sehgal (London, 1976; he lives in Berlin), and Judi Werthein (Buenos Aires, 1967; she lives in Miami). This is the first time most of these artists have shown their work in Argentina. The exhibition is born of a question: Is a live museum—where the works act, speak, move about, and live eternally—possible? For Agustín Pérez Rubio, artistic director of MALBA and curator of the exhibition: “The works in Experiencia Infinita are particularly concerned with the idea of the living as work and as a component of a kind of art that ensues not only in time but also in space: experience as journey, different situations that take place one after another,” he explains. -

CHILDREN MAKE the DECISION Kunsten Museum of Modern Art Alborg 11 October - 25 November 2018

! PRESS RELEASE October 2018 CHILDREN MAKE THE DECISION Kunsten Museum of Modern Art Alborg 11 October - 25 November 2018 Kunsten Museum of Modern Art in Aalborg will soon be unveiling a controversial work of art. It does not exist materially. It is you and 1,500 local children who will create it. Does something that does not materially exist, but rather only in the experience and memory, have any value? Does anything of value actually have to be measured and weighed? What would happen if the hierarchy were turned upside down and children did the decision-making? These are some of the questions that the world-famous German-indian artist, Tino Sehgal poses with his live artwork. It is a work that will hopefully make a profound impression on our feelings and consciousness, but will leave behind no tangible traces: no photo documentation, no written rules, no physical painting - just the experience as it takes place. Tino Sehgal is regarded as one of today’s great proponents of live art. His art will not only take over Kunsten in the physical sense of the word, but also our consciousness. The work is entitled This success/This failure, 2006. Tino Sehgal will involve museum visitors and local children, who will meet up and play in the Museum’s Main Gallery. It may sound simple at face value, but there are major considerations involved: - Tino Sehgal focuses on human resources in an age dominated by materialism, documentation requirements and digitisation. The work is fluid and open, inviting us to notice what happens if we focus only on relationships, discarding mobile phones and other objects we normally use when in contact with each other. -

Public Access in the Age of Documented Art

PUBLIC ACCESS IN THE AGE OF DOCUMENTED ART GLENN WHARTON falta afiliação ABSTRACT FALTA TRADUÇÃO Ephemerality and variability in contemporary art is fostering an age of documentation within museums. Conservators, curators, and other museum professionals spend an increasing amount of resources documenting technical details and conceptual underpinnings in an effort to provide a knowledge base for future staff that will design new exhibitions and conduct conservation interventions. The resulting archives contain information about production methods, materials, past manifestations, and artists’ concerns that can inform art history, art criticism, and public understanding. This article proposes activating these closed archives by opening them to scholars, educators, and the public. In addition to providing access for greater awareness, further benefit can be gained through participatory programming that promotes public contributions in a form of crowd documentation. The article traces ethical, legal, and artistic challenges to greater transparency of museum documentation. Despite these hurdles, tools are emerging that facilitate public access and participation in documenting the art of our times. KEYWORDS CONTEMPORARY ART; CROWD DOCUMENTATION; MEDIA ART CONSERVATION; METADATA; PUBLIC ACCESS RHA 04 174 DOSSIER PUBLIC ACCESS IN THE AGE OF DOCUMENTED ART – – – – – – – – – – – – Introduction This buildup of documentation is now common practice 1 For more information about IKEA arly in 2012 I was contacted by the Architecture for conceptual, ephemeral, and variable works. Creating Disobedients see: http://www.moma.org/ collection/object.php?object_id=156886; Eand Design Department at the Museum of Modern this documentation involves considerable time and labor http://cargocollective.com/anapenalba/ Art (MoMA) where I served as Media Conservator. They to record what the work has been, what it is, and what it Collaboration-ANDRES-JAQUE (Accessed July 20, 2014). -

Moma DEEPENS COMMITMENT to COLLECTING, PRESERVING, and EXHIBITING PERFORMANCE ART THROUGH a RANGE of PIONEERING INITIATIVES

MoMA DEEPENS COMMITMENT TO COLLECTING, PRESERVING, AND EXHIBITING PERFORMANCE ART THROUGH A RANGE OF PIONEERING INITIATIVES NEWLY NAMED DEPARTMENT OF MEDIA AND PERFORMANCE ART RECOGNIZES THE INFLUENTIAL ROLE OF PERFORMANCE IN CONTEMPORARY ARTISTIC PRACTICE NEW YORK, February 27, 2009—The Museum of Modern Art has increased its focus on performance-based art with a range of pioneering initiatives: a new exhibition series, an ongoing series of workshops for artists and curators, major acquisitions, and a retrospective of the work of performance artist Marina Abramović in 2010. In recognition of the importance of performance art in contemporary artistic practice, the Department of Media has been renamed the Department of Media and Performance Art, a first of its kind. Under the direction of Chief Curator Klaus Biesenbach, the department will maintain its focus on time-based works in a gallery setting, such as moving image installations, sound- and video- based works and will include exhibitions and acquisitions of important works of performance art. Among the department’s most recent acquisitions include seminal performance-based works by Francis Alÿs, Paul Chan, Joan Jonas, Tino Sehgal, and others. Mr. Biesenbach and Jenny Schlenzka, in the newly created position of Assistant Curator for Performance, will organize the Performance Exhibition Series, a two-year series of exhibitions that will bring installations documenting past performances, live re-enactments of historic performances, and original performance pieces to various locations throughout the Museum; and the ongoing Performance Workshops, which bring together internationally renowned artists and curators to work on, discuss, and envision the relationship between art institutions and performance-based art. -

Thesis Uncoupled from

THE ART OF CONNECTION RETHINKING ART IN A NETWORKED WORLD JANIS LEJINS - U5006313 May, 2016 Bachelor of Arts, Honours in Art History The Australian National University This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Honours in Art History in the College of Arts and Social Science (19,516 words) !1 of 122! ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY THIS PROJECT WAS CONDUCTED ON NGUNNAWHAL AND NGAMBRI LAND. I RESPECT THEIR ELDERS, PAST AND PRESENT. I RECOGNISE THAT THEIR SOVEREIGNTY WAS NEVER CEDED. !2 of 122! DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I, Janis Lejins, declare that the material presented here is the outcome of research I have undertaken during my candidacy. I am the sole author unless otherwise indicated. To the best of my ability I have documented the source of ideas, quotations or paraphrases attributable to other authors. !3 of 122! ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS BRONWYN OLIVER, MARTIN SHARP, ROBERT WICKHAM, CHERYL MCCANN, KATHERINE KYRIACOU, FIONA CRAWFORD, MATTHEW BRUCE, JOHN HARTLEY, MICHAEL HEANEY, STELLA TALATI, MARCO BOHR, MARTYN JOLLY, JASON 0’BRIEN, JP DEMARIS, ALISTAIR RIDDELL, DENISE FERRIS, DAVID BERRIDGE, CATHIE LAUDENBACH, PETER FITZPATRICK, MICKY ALLEN, FRANK MACONOCHIE, TONY STEEL, JOHN REID, MARZENA WASIKOWSKA, ROBERT WELLINGTON, HELEN ENNIS, CHARLOTTE GALLOWAY, CHAITANYA SAMBRANI, ELISABETH FINDLAY, ANDREW MONTANNA, GORDON BULL, NIGEL LENDON, KATE MURPHY, JACQUELINE BRADLEY, ROY MERCHANT, HARRY TOWNSEND, MARCIA LOCHHEAD, LUCIEN LEON, ROWAN CONROY, TIM BROOK, KIT DEVINE, RAQUEL ORMELLA, DAVID BROKER - AND EVERYONE ELSE WHO HAS TAUGHT ME ART. THE INNUMERABLE FRIENDS AND FAMILY (PAST AND PRESENT) WHO HAVE GIVEN ME UNRELENTING LOVE AND SUPPORT. THANK YOU. !4 of 122! ABSTRACT This thesis examines how elements of the contemporary artworld can be seen to adapt in relation to an increasingly networked twenty-first century world. -

Contents Project Organisation 2 Introduction 4

contents Project organisation 2 Introduction 4 Ignasi Aballí, Finestre 6 Arthur Barrio, Interminàvel 6 Krzysztof M. Bednarski, Grass just Grass 8 Phil Collins, they shoot horses 8 Ángela de la Cruz, Larger than Life 0 Tacita Dean, Disappearance at Sea 0 Olafur Eliasson, Notion Motion 2 Ger van Elk, The wider the flatter 2 Carlos Garaicoa, Letter to the Censors 4 Johan Grimonprez, Inflight 4 Thomas Hirschhorn, Doppelgarage 6 Jenny Holzer, Installation for Bilbao 6 Suchan Kinoshita, Untitled 8 Suchan Kinoshita, Voorstelling 8 Joseph Kosuth, Glass (one and three) 20 Greg Lynn & Fabian Marcaccio, The Predator 20 Gustav Metzger, Liquid Crystal Environment 22 Bruce Nauman, MAPPING THE STUDIO II with color shift, flip, flop & flip/flop (Fat Chance John Cage) 22 No Ghost Just a Shell, initiated by Pierre Huyghe & Philippe Parreno 24 Dennis Oppenheim, Circle Puppets 24 Nam June Paik, One Candle 26 Panamarenko, The Aeromodeller OO-PL 26 Javier Pérez, Un pedazo de cielo cristalizado 28 Fabrizio Plessi, Liquid Time II 28 Ulrike Rosenbach, Don’t think I am an Amazon 30 Tino Sehgal, This is Propaganda 30 Jeffrey Shaw & Tjebbe van Tijen, Revolution (a monument for the television revolution) 32 Ross Sinclair, Journey to the Edge of the World - The New Republic of St. Kilda 32 Bill Spinhoven, Albert’s Ark 34 Joëlle Tuerlinckx, Ensemble autour du MUR 34 Eulàlia Valldosera, Flying #1 New York 36 Franz West, Clamp 36 Gilberto Zorio, Los Zorios 38 research activities The preservation of installations 40 Artist Participation 45 Documentation Model (2IDM)