Contents Project Organisation 2 Introduction 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kris Dittel Curator and Editor. Born in 1983, Slovakia. Lives and Works in Rotterdam. Contact: [email protected] EDUCATION AN

Kris Dittel Curator and editor. Born in 1983, Slovakia. Lives and works in Rotterdam. Contact: [email protected] EDUCATION AND PROFESSIONAL TRAINING 2013-14 De Appel Curatorial Programme, Amsterdam 2009-10 Maastricht University, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences MA, Arts and Heritage 2001-06 Masaryk University Brno, Czech Republic, Faculty of Economics and Administration MSc, Economic Policy and Administration CURATORIAL EXPERIENCE AND POSITIONS HELD 2020 To Be Like Water, curator, exhibition and public programme Sculpture International Rotterdam (cancelled) 2019 Post-Opera, co-curated with Jelena Novak, exhibition, performance programme Installing the Voice, symposium, convened with Jelena Novak at TENT Rotterdam, V2_Lab for Unstable Media, and Operadagen Rotterdam festival 2017-18 The Trouble with Value, co-curated with Krzysztof Siatka Bunkier Sztuki, Krakow, PL and Onomatopee Projects, Eindhoven, NL 2016-17 Associate curator, Onomatopee Projects: Marjolijn Dijkman: That What Makes Us Human, solo exhibition and publication The Economy is Spinning, group exhibition and publication Eva Olthof: Return to Rightful Owner, solo exhibition i.c.w. Van Abbemuseum Eindhoven 2015-17 The Translation Trip - nomadic joint research trajectory with Sara Giannini 2016 Unfold, guest-curator, online publishing and archiving platform 2015 Curator, Onomatopee Projects (selected solo projects): Helen Cho: 21 Objects for Hesitation Tbilisi InSights: city [un]archived, exhibition and seminar Anna Bak: Wilderness Survival, exhibition and performance Maria -

Jaarboek-Maastricht-1997-1998.Pdf

Jaar boek Maastricht l augustus 1997 tot en met 31 juli 1998 samenstellers: Flor Aarts Yvonne Huitema Henk Leenen Servé Minis Maastricht r998 I 1 j aarboek Maastri cht colofon RE DACTI E Henk Leenen (vz) Flor Aarts Servé Minis Yvonne Huitema Joep Offermans UIT GEVE R Stichting Jaarboek Maastricht Hertogsingel 19b 62n NC Maastricht onder bestuur van Jean Daenen (vz) Kitty Otten (secr) Harry Paulussen (pen) Paul Rinkens VOR MGEVIN G Jo Hendriks bNO, Cottessen PAPIE R Sappi Nederland BV, Maastricht DRUK Casparie, Maastricht SPONSO R S Buro Jo Hendriks bNO, Cottessen Casparie drukkerij, Maastricht Codacq Projectmanagement BV, Maastricht De Limburger Uitgeversmaatschappij b.v., Maastricht ENCI Nederland b.v., Maastricht Hotel Bergère, Maastricht LoodgietersbedrijfHogenboom BV, Maastricht Masco Schilders, Maastricht Melotte Installatietechniek b.v., Maastricht N.V. Nutsbedrijven, Maastricht Sappi Nederland BV, Maastricht N.V. Koninklijke Sphinx Gustavsberg, Maastricht Struyscomité Gebr.Theunissen Bouw B.V., Maastricht Woningbouwvereniging 'Beter Wonen', Maastricht Kantoren Fonds Nederland, Maastricht 2 1 j aa rb otk Ma astricht inhoud VOORWOORD 5 AUGUSTUS 7 SEPTEMBER 9 EEN 'LIMBURGSE' MEDIA-MAN 12 OKTOBER 13 NOVEMBER 16 HET BONNEFANTENMUSEUM IN HET NIEUWS 20 DECEMBER 21 JANUARJ 25 FEBRUARI 29 DE KAMER VAN KOOPHANDEL EN FABRIEKEN IN ZUID LIMBURG 32 MAART 33 KANTOREN FONDS NEDERLAND, EEN KLEINE ORGANISATIE MET EEN GROTE IMPACT 36 APRIL 39 OUD-WETHOUDERA. CREMERS 42 MB ~ JUNI 47 TOERISTISCH MAASTRICHT 51 JULI 52 3 1 Jaarbotk Maastricht STICHTING JAARBOEK TRICHT © 1998, Stichtin.gjaarboek Maastricht Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niet uit deze uitgave mag worden verveel voudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, ofopen· baar worden gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij electro nisch, mechanisch, door fotokopieën, opnamen, ofenig andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. -

Virginia 22314 Photo by Joan Brady Free Digital Edition Delivered to Your Email Box

Senior Living Challenges for Page 11 Black Students 50 Years Later Yorktown, Page 3 Cuter by The Dozens ArPets, Page 2 Johanna Pichlkostner Isani with adopted canines Lexie and Paxton and puppy foster Bri. Classifieds, Page 10 Classifieds, Live from the Rugstore Page 4 Requested in home 4-8-21 home in Requested Time sensitive material. material. sensitive Time Marijuana Legalization Postmaster: Attention permit #322 permit Easton, MD Easton, Could Come This Summer PAID U.S. Postage U.S. News, Page 9 STD PRSRT Photo by Joan Brady/Arlington Connection Photo April 7-13, 2021 online at www.connectionnewspapers.com ArPets The Arlington Connection www.ConnectionNewspapers.com @ArlConnection An independent, locally owned weekly newspaper delivered to homes and businesses. Published by Local Media Connection LLC 1606 King Street Alexandria, Virginia 22314 Photo by Joan Brady Photo Free digital edition delivered to your email box. Go to connectionnewspapers.com/subscribe NEWS DEPARTMENT: [email protected] Shirley Ruhe Contributing Photographer and Writer Johanna Pichlkostner Isani with adopted canines Lexie and Paxton [email protected] and puppy foster Bri. Joan Brady Contributing Photographer and Writer Cuter by the Dozens [email protected] Eden Brown Contributing Writer 25 Dogs and Counting [email protected] Ken Moore By Joan Brady much-needed way station. Arlington Connection Contributing Writer Johanna grew up with a dog [email protected] and cat, as well as two “boy” ham- couldn’t wait to vault from my sters who had a litter. Then anoth- ADVERTISING: parents’ house into college. Full er. Then another. And over time, For advertising information Idisclosure, my college was less there wasn’t a kid in her neighbor- [email protected] than 75 miles from my childhood hood who didn’t have one of the 703-778-9431 home and about a 12 minute drive Pichlkostner hamsters. -

Download the Programme As A

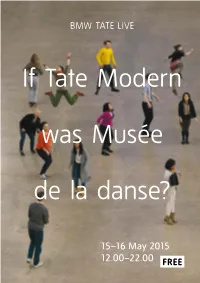

Introduction 15–16 May 2015 12.00–22.00 FREE #dancingmuseum Map Introduction BMW TATE LIVE: If Tate Modern was Musée de la danse? Tate Modern Friday 15 May and Saturday 16 May 2015 12.00–22.00 FREE Starting with a question – If Tate Modern was Musée de la danse? Restaurant – this project proposes a fictional transformation of the art museum 6 via the prism of dance. A major new collaboration between Tate Modern and the Musée de la danse in Rennes, France, directed by Members Room dancer and choreographer Boris Charmatz, this temporary 5 occupation, lasting just 48 hours, extends beyond simply inviting the 20 Dancers discipline of dance into the art museum. Instead it considers how the 4 museum can be transformed by dance altogether as one institution 20 Dancers overlaps with another. By entering the public spaces and galleries of 3 Tate Modern, Musée de la danse dramatises questions about how art might be perceived, displayed and shared from a danced and 20 Dancers expo zéro choreographed perspective. Charmatz likens the scenario to trying on 2 a new pair of glasses with lenses that opens up your perception to River Café forms of found choreography happening everywhere. Entrance 1 Shop Shop Turbine Hall Presentations of Charmatz’s work are interwoven with dance À bras-le-corps 0 to manger 0performances that directly involve viewers. Musée de la danse’s Main regular workshop format, Adrénaline – a dance floor that is open Entrance to everyone – is staged as a temporary nightclub. The Turbine Hall oscillates between dance lesson and performance, set-up and take-down, participation and party. -

Using a Projected Trompe L'oeil to Highlight a Church Interior from the Outside

Using a projected Trompe L'Oeil to highlight a church interior from the outside A. Hoeben fieldOfView Lange Nieuwstraat 23b1 3111AC Schiedam the Netherlands [email protected] The St. Willibrordus Church in the city center of Utrecht (the Netherlands) is a prime example of the Gothic Revival architecture. The richly decorated church interior is, unfortunately, one of the best kept secrets of the city. In the semi permanent art installation presented in this paper, imagery showing the church interior is projected on the outside walls of the entrance of the church. By projecting onto a spherical mirror suspended from the entrance ceiling, the projection is reflected onto three walls and the ceiling. The resulting image, when seen from the street-level outside, creates an perspective illusion. This paper shows how the installation was implemented in the church in an unobtrusive way, and explains the calibration system that was developed for determining the pre-distortions required to project the Trompe L'Oeil. church interior, art installation, digital projection, perspective manipulation, optical illusion 1. INTRODUCTION together constitute a walking route through the city center under the name “Trajectum Lumen”. The In late 2007, the council of the city of Utrecht Trajectum Lumen was officially launched on April embarked on a project to create a new attraction 7th 2010, and will have its climax in 2013 when the for its historic city center, aiming to keep some of city of Utrecht celebrates the 300th anniversary of the shopping public around during the evening the Treaty of Utrecht. hours. 1.1 St. Willibrord church A number of semi-permanent light art installations and sculptures was commissioned from different The St. -

Installation Art in India: Concepts and Roots

[Aaftab *, Vol.4 (Iss.10): October, 2016] ISSN- 2350-0530(O) ISSN- 2394-3629(P) IF: 4.321 (CosmosImpactFactor), 2.532 (I2OR) Arts INSTALLATION ART IN INDIA: CONCEPTS AND ROOTS Mohsina Aaftab *1 *1 Research Scholar, Department of Fine Arts, A.M.U., Aligarh, INDIA DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.164831 ABSTRACT Present study focuses on the new media Installation Art in India, its present scenario, and backgrounds. Essentially installation art has taken its heritage from conceptual art, which came into prominence in 1970s, when the concept or idea was prominent – when an artist uses a conceptual form of art which means that all of the arrangement and conclusion are made previously and the implementation is an obligatory concern. So, spontaneously idea became a machine that makes the art. An idea suddenly pops in his mind and he just implemented it, in his very own way. This kind of art does not narrow itself to gallery spaces and can refer to any materials intervention in everyday public or private spaces. After India became independent, art began to change here. considerately several movements and group bounced up all over the country headed by ambitious young artists with vision of bringing modern art to India. Now the art of India is totally changed. Contemporaries are not bound to use paper and canvas, wall or any other art surfaces. They are not bound to make mythological paintings or sculptures but they are free to do anything, they are free to use any medium, material and space they want. After a European artist Marcel Duchamp’s “ready-mades artist” started exploring the margin of art, trying to eliminate the contrast between art and life. -

AP Art History Unit Sheet #21 Romanticism, Realism, and Photography

AP Art History Unit Sheet #21 Romanticism, Realism, and Photography Works of Art Artist Medium Date Page # 27‐1: Napoleon at the Plague House at Jaffa Gros Painting 1804 754 27‐2: Coronation of Napoleon David Painting 1805‐1808 757 27‐4: Pauline Borghese as Venus Canova Sculpture 1808 759 27‐6: Apotheosis of Homer Ingres Painting 1827 761 27‐7: Grande Odalisque Ingres Painting 1814 761 27‐8: The Nightmare Fuseli Painting 1781 762 27‐9: Ancient of Days Blake Painting 1794 763 27‐10: The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters Goya Painting 1798 763 27‐11: Third of May, 1808 Goya Painting 1814‐1815 764 27‐13: The Raft of the Medusa Gericault Painting 1819 765 27‐16: Liberty Leading the People Delacrois Painting 1830 768 27‐19: Abbey in the Oak Forest Friedrich Painting 1810 771 27‐21: The Haywain Constable Painting 1821 772 27‐22: The Slave Ship Turner Painting 1840 773 27‐23: The Oxbow ColePainting1836 773 27‐26: The Stone Breakers Courbet Painting 1849 775 27‐27: Burial at Ornans Courbet Painting 1849 776 27‐28: The Gleaners Millet Painting 1857 777 27‐30: Third Class Carriage Daumier Painting 1862 779 27‐31: The Horse Fair Bonheur Painting 1853‐1855 780 27‐32: Le Dejeauner sure l’herbe Manet Painting 1863 781 27‐33: Olympia Manet Painting 1863 781 27‐35: Veteran in a New Field Homer Painting 1865 783 27‐36: The Gross Clinic Eakins Painting 1875 783 27‐37: The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit Sargent Painting 1882 784 27‐38: The Thankful Poor Tanner Painting 1894 785 27‐40: Ophelia Millais Painting 1852 786 27‐43: House of Parliament, London Pugin/ Barry Architecture 1835 788 27‐44: Royal Pavilion, Brighton Nash Architecture 1815‐1818 789 27‐45: Paris Opera Garnier Architecture 1861‐1874 789 27‐48: Still Life in Studio Daguerre Photography 1837 792 27‐51: Nadar Raising Photography to the Height of Art Daumier Lithograph 1862 794 27‐53: A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania O’Sullivan Photography 1863 795 27‐54: Horse Galloping Muybridge Calotype 1878 796 CONTEXT Europe and France 1. -

Chapter 12. the Avant-Garde in the Late 20Th Century 1

Chapter 12. The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century 1 The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century: Modernism becomes Postmodernism A college student walks across campus in 1960. She has just left her room in the sorority house and is on her way to the art building. She is dressed for class, in carefully coordinated clothes that were all purchased from the same company: a crisp white shirt embroidered with her initials, a cardigan sweater in Kelly green wool, and a pleated skirt, also Kelly green, that reaches right to her knees. On her feet, she wears brown loafers and white socks. She carries a neatly packed bag, filled with freshly washed clothes: pants and a big work shirt for her painting class this morning; and shorts, a T-shirt and tennis shoes for her gym class later in the day. She’s walking rather rapidly, because she’s dying for a cigarette and knows that proper sorority girls don’t ever smoke unless they have a roof over their heads. She can’t wait to get into her painting class and light up. Following all the rules of the sorority is sometimes a drag, but it’s a lot better than living in the dormitory, where girls have ten o’clock curfews on weekdays and have to be in by midnight on weekends. (Of course, the guys don’t have curfews, but that’s just the way it is.) Anyway, it’s well known that most of the girls in her sorority marry well, and she can’t imagine anything she’d rather do after college. -

ART, TECHNOLOGY, and HIGH ART/LOW CULTURE DEBATES in CANONICAL AMERICAN ART HISTORY I. Overview in His Media Ar

CHAPTER ONE: ART, TECHNOLOGY, AND HIGH ART/LOW CULTURE DEBATES IN CANONICAL AMERICAN ART HISTORY I. Overview In his Media Art History, Hans-Peter Schwarz of the Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, Germany (ZKM) wrote: “The history of the new media [sic] is inextricably linked with the history of the project of the modern era as a whole. It can only be described as the evolution of the human experience of reality, i.e. of the social reality relationship in the modern age.” I begin with his words, which have strong resonance for me, perhaps beyond his initial intent or ultimate direction. His astute triangulation of those three concepts—new media history, the project of the modern era, and “social reality”—form the nexus of my theoretical investigation. For it seems that current social realities and the project of the modern era largely govern new media’s reception within the Western art history canon. Perhaps clarity regarding the ideological interconnection of these three elements will only be possible with more historical distance. However, this dissertation represents a step toward a better understanding of the sometimes-vicious canonical opposition to the fusion of art and technology, in light of these intersections. Key are his two phrases: “the project of the modern era,” and “the evolution of the human experience of reality, i.e. of the social reality relationship in the modern age.” On the basis of Schwarz’s text, I take the second phrase to mean the dehumanization that results from industrialization and modern warfare. In regard to artistic production, he rightly underscores the abrupt reorganization of vision precipitated by, for example, developments in photography and cinematography during the early modernist period. -

Video Installation in Public Space

Center for Open Access in Science ▪ https://www.centerprode.com/ojsa.html Open Journal for Studies in Arts, 2018, 1(1), 29-42. ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 ▪ https://doi.org/10.32591/coas.ojsa.0101.03029d _________________________________________________________________________ Video Installation in Public Space Lili Atila Dzhagarova South-West University “Neofit Rilski”, Blagoevgrad Theater and Cinema Art Received 31 May 2018 ▪ Revised 27 June 2018 ▪ Accepted 29 July 2018 Abstract The present study is dedicated to the research of video installations placed in the public space, such as exhibition halls, streets and theatrical spaces. The theme “Video installations in the public space” is the understanding of the essence of video and space and its aspects through the production of various spatial solutions and practical imaging solutions in the field of video art. The subject of the study is essence of the problem. In the case of this study the object is the video installations, and the subject is the process of their creation, and the concept of environment. The whole range of phenomena studied is related to the works of video art, their development and expression of opportunities and the idea of environment is an aspect of exploring the space in which they are presented. Keywords: installations, video, public space, phenomenon, movement. 1. Introduction When we think of artists, we think of paint on canvas, or clay masterpieces, or beautiful, timeless drawings, but what do you think when you hear digital artists? The acceptance of digital art into the mainstream art community is a controversy that is slowly becoming history. The controversy is essentially what many people believe in that art is created by the computer, and not by the artist. -

Janson. History of Art. Chapter 16: The

16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 556 16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 557 CHAPTER 16 CHAPTER The High Renaissance in Italy, 1495 1520 OOKINGBACKATTHEARTISTSOFTHEFIFTEENTHCENTURY , THE artist and art historian Giorgio Vasari wrote in 1550, Truly great was the advancement conferred on the arts of architecture, painting, and L sculpture by those excellent masters. From Vasari s perspective, the earlier generation had provided the groundwork that enabled sixteenth-century artists to surpass the age of the ancients. Later artists and critics agreed Leonardo, Bramante, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giorgione, and with Vasari s judgment that the artists who worked in the decades Titian were all sought after in early sixteenth-century Italy, and just before and after 1500 attained a perfection in their art worthy the two who lived beyond 1520, Michelangelo and Titian, were of admiration and emulation. internationally celebrated during their lifetimes. This fame was For Vasari, the artists of this generation were paragons of their part of a wholesale change in the status of artists that had been profession. Following Vasari, artists and art teachers of subse- occurring gradually during the course of the fifteenth century and quent centuries have used the works of this 25-year period which gained strength with these artists. Despite the qualities of between 1495 and 1520, known as the High Renaissance, as a their births, or the differences in their styles and personalities, benchmark against which to measure their own. Yet the idea of a these artists were given the respect due to intellectuals and High Renaissance presupposes that it follows something humanists. -

BRADFORD ART ASSIGNMENT FINAL EDIT-Merged-Compressed (1

ART ASSIGNMENT OPEN CALL MARK BRADFORD In conjunction with the exhibition Mark Bradford: End Papers, the Modern’s education department is pleased to announce an OPEN CALL for high school and middle school student responses to two key works in the show, Medusa, 2020, and Kingdom Day, 2010. It is highly recommended that each student visits the Modern’s galleries to view the selected works in person. The exhibition is on view through January 10, 2021. This packet is a supplement to the gallery experience and offers background information on the artist and works, as well as ideas to consider and activities to complete for the open call. Admission to the Modern is free for participating students. OPEN CALL submission guidelines can be found at the end of this packet. Mark Bradford (b. 1961 in Los Angeles; lives and works in Los Angeles) is a contemporary artist best known for his large-scale abstract paintings created out of paper. Characterized by its layered formal, material, and conceptual complexity, Bradford’s work explores social and political structures that objectify marginalized communities and the bodies of vulnerable populations. Just as essential to Bradford’s work is a social engagement practice through which he reframes objectifying societal structures by bringing contemporary art and ideas into communities with limited access to museums and cultural institutions. Bradford grew up in his mother’s beauty salon, eventually becoming a hairdresser himself, and was quite familiar with the small papers used to protect hair from overheating during the process for permanent waves. Incorporating them into his art was catalytic for Bradford, merging his abstract painting with materials from his life.