Thesis Uncoupled from

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tate Report 2010-11: List of Tate Archive Accessions

Tate Report 10–11 Tate Tate Report 10 –11 It is the exceptional generosity and vision If you would like to find out more about Published 2011 by of individuals, corporations and numerous how you can become involved and help order of the Tate Trustees by Tate private foundations and public-sector bodies support Tate, please contact us at: Publishing, a division of Tate Enterprises that has helped Tate to become what it is Ltd, Millbank, London SW1P 4RG today and enabled us to: Development Office www.tate.org.uk/publishing Tate Offer innovative, landmark exhibitions Millbank © Tate 2011 and Collection displays London SW1P 4RG ISBN 978-1-84976-044-7 Tel +44 (0)20 7887 4900 Develop imaginative learning programmes Fax +44 (0)20 7887 8738 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Strengthen and extend the range of our American Patrons of Tate Collection, and conserve and care for it Every effort has been made to locate the 520 West 27 Street Unit 404 copyright owners of images included in New York, NY 10001 Advance innovative scholarship and research this report and to meet their requirements. USA The publishers apologise for any Tel +1 212 643 2818 Ensure that our galleries are accessible and omissions, which they will be pleased Fax +1 212 643 1001 continue to meet the needs of our visitors. to rectify at the earliest opportunity. Or visit us at Produced, written and edited by www.tate.org.uk/support Helen Beeckmans, Oliver Bennett, Lee Cheshire, Ruth Findlay, Masina Frost, Tate Directors serving in 2010-11 Celeste -

Download the Programme As A

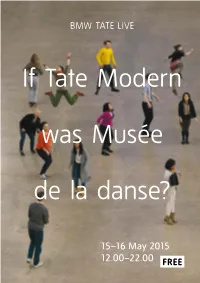

Introduction 15–16 May 2015 12.00–22.00 FREE #dancingmuseum Map Introduction BMW TATE LIVE: If Tate Modern was Musée de la danse? Tate Modern Friday 15 May and Saturday 16 May 2015 12.00–22.00 FREE Starting with a question – If Tate Modern was Musée de la danse? Restaurant – this project proposes a fictional transformation of the art museum 6 via the prism of dance. A major new collaboration between Tate Modern and the Musée de la danse in Rennes, France, directed by Members Room dancer and choreographer Boris Charmatz, this temporary 5 occupation, lasting just 48 hours, extends beyond simply inviting the 20 Dancers discipline of dance into the art museum. Instead it considers how the 4 museum can be transformed by dance altogether as one institution 20 Dancers overlaps with another. By entering the public spaces and galleries of 3 Tate Modern, Musée de la danse dramatises questions about how art might be perceived, displayed and shared from a danced and 20 Dancers expo zéro choreographed perspective. Charmatz likens the scenario to trying on 2 a new pair of glasses with lenses that opens up your perception to River Café forms of found choreography happening everywhere. Entrance 1 Shop Shop Turbine Hall Presentations of Charmatz’s work are interwoven with dance À bras-le-corps 0 to manger 0performances that directly involve viewers. Musée de la danse’s Main regular workshop format, Adrénaline – a dance floor that is open Entrance to everyone – is staged as a temporary nightclub. The Turbine Hall oscillates between dance lesson and performance, set-up and take-down, participation and party. -

Important Australian and Aboriginal

IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including The Hobbs Collection and The Croft Zemaitis Collection Wednesday 20 June 2018 Sydney INSIDE FRONT COVER IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including the Collection of the Late Michael Hobbs OAM the Collection of Bonita Croft and the Late Gene Zemaitis Wednesday 20 June 6:00pm NCJWA Hall, Sydney MELBOURNE VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION Tasma Terrace Online bidding will be available Merryn Schriever OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION 6 Parliament Place, for the auction. For further Director PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE East Melbourne VIC 3002 information please visit: +61 (0) 414 846 493 mob IS NO REFERENCE IN THIS www.bonhams.com [email protected] CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL Friday 1 – Sunday 3 June CONDITION OF ANY LOT. 10am – 5pm All bidders are advised to Alex Clark INTENDING BIDDERS MUST read the important information Australian and International Art SATISFY THEMSELVES AS SYDNEY VIEWING on the following pages relating Specialist TO THE CONDITION OF ANY NCJWA Hall to bidding, payment, collection, +61 (0) 413 283 326 mob LOT AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 111 Queen Street and storage of any purchases. [email protected] 14 OF THE NOTICE TO Woollahra NSW 2025 BIDDERS CONTAINED AT THE IMPORTANT INFORMATION Francesca Cavazzini END OF THIS CATALOGUE. Friday 14 – Tuesday 19 June The United States Government Aboriginal and International Art 10am – 5pm has banned the import of ivory Art Specialist As a courtesy to intending into the USA. Lots containing +61 (0) 416 022 822 mob bidders, Bonhams will provide a SALE NUMBER ivory are indicated by the symbol francesca.cavazzini@bonhams. -

Art Gallery of New South Wales Annual Report 2001

ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES ANNUAL REPORT 2001 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES HIGHLIGHTS PRESIDENT’S REPORT 2 NEW ATTENDANCE RECORD SET FOR THE POPULAR ARCHIBALD, WYNNE AND SULMAN PRIZES, WHICH HAD MORE THAN 98,000 VISITORS. DIRECTOR’S REPORT 4 1 YEAR IN REVIEW 8 TWO NEW MAJOR AGNSW PUBLICATIONS, AUSTRALIAN ART IN THE ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES AND PAPUNYA TULA: GENESIS AIMS/OBJECTIVES/PERFORMANCE INDICATORS 26 2 AND GENIUS. CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 32 DEDICATION OF THE MARGARET OLLEY TWENTIETH CENTURY EUROPEAN LIFE GOVERNORS 34 3 GALLERIES IN RECOGNITION OF HER CONTINUING AND SUBSTANTIAL SENIOR MANAGEMENT PROFILE 34 ROLE AS A GALLERY BENEFACTOR. ORGANISATION CHART 36 COLLECTION ACQUISITIONS AMOUNTED TO $7.8 MILLION WITH 946 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 41 4 PURCHASED AND GIFTED WORKS ACCESSIONED INTO THE PERMANENT COLLECTION.TOTAL ACQUISITIONS HAVE GROWN BY MORE THAN $83.4 APPENDICES 62 MILLION IN THE PAST 10 YEARS. INDEX 92 MORE THAN 1.04 MILLION VISITORS TO OVER 40 TEMPORARY, TOURING GENERAL INFORMATION 93 5 AND PERMANENT COLLECTION EXHIBITIONS STAGED IN SYDNEY, REGIONAL NSW AND INTERSTATE. COMMENCED A THREE-YEAR, $2.3 MILLION, NSW GOVERNMENT 6 FUNDED PROGRAMME TO DIGITISE IMAGES OF ALL WORKS IN THE GALLERY’S PERMANENT COLLECTION. Bob Carr MP Premier, Minister for the Arts, and Minister for Citizenship DEVELOPED GALLERY WEBSITE TO ALLOW ONLINE USERS ACCESS TO Level 40 7 DATABASE INFORMATION ON THE GALLERY’S COLLECTION, INCLUDING Governor Macquarie Tower AVAILABLE IMAGES AND SPECIALIST RESEARCH LIBRARY CATALOGUE. 1 Farrer Place SYDNEY NSW 2000 CREATED A MAJOR NEW FAMILY PROGRAMME, FUNDAYS AT THE 8 GALLERY, IN PARTNERSHIP WITH A FIVE-YEAR SPONSORSHIP FROM THE Dear Premier, SUNDAY TELEGRAPH. -

Exhibiting Performance Art's History

EXHIBITING PERFORMANCE ART’S HISTORY Harry Weil 100 Years (version #2, ps1, nov 2009), a group show at MoMA PS1, Long Island City, New York, November 1, 2009 –May 3, 2010 and Off the Wall: Part 1—Thirty Performative Actions, a group show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, July 1–September 19, 2010. he past decade has born witness 100 Years, curated by MoMA PS1 cura- to the proliferation of perfor- tor Klaus Biesenbach and art historian mance art in the broadest venues RoseLee Goldberg, structured a strictly Tyet seen, with notable retrospectives of linear history of performance art. A Marina Abramović, Gina Pane, Allan five-inch thick straight blue line ran the Kaprow, and Tino Sehgal held in Europe length of the exhibition, intermittently and North America. Performance has pierced by dates written in large block garnered a space within the museum’s letters. The blue path mimics the simple hallowed halls, as these institutions have red and black lines of Alfred Barr’s chart hurriedly begun collecting performance’s on the development of modern art. Barr, artifacts and documentation. As such, former director of MoMA, created a museums play an integral role in chroni- simple scientific chart for the exhibition cling performance art’s little-detailed Cubism and Abstract Art (1935) that history. 100 Years (version #2, ps1, nov streamlines the genealogy of modern 2009) at MoMA PS1 and Off the Wall: art with no explanatory text, reduc- Part 1—Thirty Performative Actions at ing it to a chronological succession of the Whitney Museum of American avant-garde movements. -

Ari Benjamin Meyers

ARI BENJAMIN MEYERS Born 1972 (New York, USA) Lives and works in Berlin, Germany EDUCATION 1996–1998 Fullbright Grant: Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler, Berlin, Germany, Certificate in Conducting 1994–1996 The Peabody Institue, Baltimore, Maryland, USA, MM Conducting 1990–1994 Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA, BA Composition (Cum Laude) 1990–1997 The Juilliard School Pre-College Division, New York, New York, USA, Composition and Piano SOLO EXHIBITIONS AND PRESENTATIONS 2019 In Concert, OGR – Officine Grandi Riparazioni, Turin, Italy 2018 Kunsthalle for Music, Witte de With, Rotterdam, Netherlands 2017 An exposition, not an exhibition, Spring Workshop, Hong Kong, China Solo for Ayumi, Esther Schipper, Berlin, Germany 2016 The Name Of This Band is The Art, RaebervonStenglin, Zurich, Switzerland 2015 Atlas of Melodies, abc Berlin, Berlin, Germany 2013 Black Thoughts, Esther Schipper, Berlin, Germany Songbook, Esther Schipper, Berlin, Germany SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2016 Musikwerke Bildene Künstler, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, Germany Oscillations, Trafo Center for Contemporary Art, Szczecin, Poland 2015 music, Fahrbereitschaft – Haubrok Collection, Berlin, Germany Artists’ Weekend, Ngorongoro, Berlin, Germany The Verismo Project, Kunst im Kino, Kino International, Berlin, Germany 2014 Supergroup, Tanzhaus NRW, Düsseldorf, Germany I Take Part and the Part Takes Me, Gallery Tanja Wagner, Berlin, Germany The New Empirical, Hatje Cantz & Du Moulin im Bikini, Berlin, Germany 2012 I Wish This Was a Song. Music in Contemporary Art, -

Branding of the Museum

The Branding of the Museum Julian Stallabrass [‘Brand Strategy of Art Museum’, in Wang Chunchen, ed., University and Art Museum, Tongji University Press, Shanghai 2011, published in Chinese. Also published in Cornelia Klinger, ed., Blindheit und Hellsichtigkeit: Künstlerkritik an Politik und Gesellschaft der Gegenwart, Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2013, pp. 303-16; and in a revised and updated version as ‘The Branding of the Museum’, Art History, vol. 37, no. 1, February 2014, pp. 148-65.] The British Museum shop, 2008. Photo: JS While museums have long had names, identities and even logos, their explicit branding by specialist companies devoted to such tasks is relatively new.1 The brand is an attempt to 1 This piece has had a long gestation, and has benefitted from the comments of many participants at lectures and symposia. As a talk, it was first given at the CIMAM 2006 Annual Conference, Contemporary Institutions: Between Public and Private, held at Tate Modern. In the large literature about museums and their changing roles, there has slowly begun to emerge some consideration of branding. Margot A. Wallace, Museum Branding: How to Create and Maintain Image, Loyalty and Support, AltaMira Press, Oxford 2006 is, as its title suggests, a how-to guide. James B. Twitchell, Branded Nation: The Marketing of Megachurch, College Inc. and Museumworld, Simon & Schuster, New York 2004 is a jocular lament about the pervasiveness of marketing culture, which sees the museum, too simply, as providing ‘edutainment’ with no meaningful differentiation from consumer culture. More seriously, Andrew Dewdney/ David Bibosa/ Victoria Walsh, Post-Critical Museology: Theory and Practice in Stallabrass, Branding, p. -

4. Contemporary Art in London

저작자표시-비영리-변경금지 2.0 대한민국 이용자는 아래의 조건을 따르는 경우에 한하여 자유롭게 l 이 저작물을 복제, 배포, 전송, 전시, 공연 및 방송할 수 있습니다. 다음과 같은 조건을 따라야 합니다: 저작자표시. 귀하는 원저작자를 표시하여야 합니다. 비영리. 귀하는 이 저작물을 영리 목적으로 이용할 수 없습니다. 변경금지. 귀하는 이 저작물을 개작, 변형 또는 가공할 수 없습니다. l 귀하는, 이 저작물의 재이용이나 배포의 경우, 이 저작물에 적용된 이용허락조건 을 명확하게 나타내어야 합니다. l 저작권자로부터 별도의 허가를 받으면 이러한 조건들은 적용되지 않습니다. 저작권법에 따른 이용자의 권리는 위의 내용에 의하여 영향을 받지 않습니다. 이것은 이용허락규약(Legal Code)을 이해하기 쉽게 요약한 것입니다. Disclaimer 미술경영학석사학위논문 Practice of Commissioning Contemporary Art by Tate and Artangel in London 런던의 테이트와 아트앤젤을 통한 현대미술 커미셔닝 활동에 대한 연구 2014 년 2 월 서울대학교 대학원 미술경영 학과 박 희 진 Abstract The practice of commissioning contemporary art has become much more diverse and complex than traditional patronage system. In the past, the major commissioners were the Church, State, and wealthy individuals. Today, a variety of entities act as commissioners, including art museums, private or public art organizations, foundations, corporations, commercial galleries, and private individuals. These groups have increasingly formed partnerships with each other, collaborating on raising funds for realizing a diverse range of new works. The term, commissioning, also includes this transformation of the nature of the commissioning models, encompassing the process of commissioning within the term. Among many commissioning models, this research focuses on examining the commissioning practiced by Tate and Artangel in London, in an aim to discover the reason behind London's reputation today as one of the major cities of contemporary art throughout the world. -

Marian Goodman Gallery

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY TINO SEHGAL Born: London, England, 1976 Lives and works in Berlin Awards: Golden Lion, Venice Biennale, 2013 Shortlist for the Turner Prize, 2013 American International Association of Art Critics: Best Show Involving Digital Media, Video, Film Or Performance, 2011 SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Enoura Observatory, Odawara Art Foundation, Japan Accelerator Stockholms University, Stockholm, Sweden Tino Sehgal, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York 2018 Tino Sehgal, Kunstmuseum Stuttgart, Germany This Success, This Failure, Kunsten, Aalborg, Denmark This You, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C., USA Oficine Grandi Riparazioni, Turin, Italy 2017 Tino Sehgal, Fondation Beyeler, Switzerland V-A-C Live: Tino Sehgal, the New Tretyakov Gallery and the Schusev State Museum of Architecture, Moscow Russia 2016 Carte Blanche to Tino Sehgal, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France Jemaa el-Fna, Marrakesh, Morocco Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Lichthof, Germany Sehgal / Peck / Pite / Forsythe, Opéra de Paris, Palais Garnier, France 2015 A Year at the Stedelijk: Tino Sehgal, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Tino Sehgal, Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin, Germany Tino Sehgal, Helsinki Festival, Finland 2014 This is so contemporary, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney These Associations, CCBB, Centro Cultural Banco de Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil These Associations, Pinacoteca do Estado de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil 2013 Tino Sehgal, Musee d'Art Contemporain de Montreal, Montreal, Canada Tino Sehgal: This Situation, -

Tino Sehgal's

KALDOR PUBLIC ART PROJECT 29: TINO SEHGAL’S THIS IS SO CONTEMPORARY For the 29th Kaldor Public Art Project, internationally acclaimed artist Tino Sehgal presents This is so contemporary, from 6 – 23 February 2014 at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Kaldor Public Art Projects and the Art Gallery of New South Wales have a long-standing relationship, which began with Project 3: Gilbert and George in 1973. This is so contemporary, the third project Kaldor Public Art Projects has presented in the Gallery’s classical vestibule, is spontaneous and contagiously uplifting, directly engaging the Gallery’s visitors. Sehgal has pioneered a radical and captivating way of making art. He orchestrates interpersonal encounters through dance, voice and movement, which have become renowned for their intimacy. This is so contemporary, first presented at the 2005 Venice Biennale and making its Australian debut, is no exception. In 2013, Sehgal was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale, one of the world’s most prestigious art awards, and was shortlisted for the Tate Modern’s Turner Prize. Key recent exhibitions include This Progress at the Guggenheim New York in 2010, These Associations at the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in 2012 and This Variation at dOCUMENTA 13. Sehgal leaves no material traces, creating something that is at once valuable and entirely immaterial in a world already full of objects. His works reside only in the space and time they occupy, and in the memory of the work and its reception. In order to focus all the attention on the physical evidence, the artist does not allow his work to be photographed or illustrated - no documentation or reproduction is permitted. -

PROJECT 27 13 Rooms 2013 13 Rooms 11 – 21 April 2013 Pier 2/3, Walsh Bay, Sydney

PROJECT 27 13 Rooms 2013 13 Rooms 11 – 21 April 2013 Pier 2/3, Walsh Bay, Sydney BIOGRAPHIES HANS ULRICH OBRIST Swiss curator Hans Ulrich Obrist is Co-director of Exhibitions and Programs and Director of International Projects at the Serpentine Gallery, London. He has previously served as curator of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and Museum in Progress, Vienna. KLAUS BIESENBACH Klaus Biesenbach is Director of MoMA PS1 in New York and a Chief Curator at Large at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. He was the Founding Director of both the Kunst- Werke Institute of Contemporary Art in Berlin and the Berlin Biennale. Key international exhibitions organised by Biesenbach include MoMA’s landmark show Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present (2010) and Hybrid Workspace at documenta X (Kassel, 1997 ). EXHIBITING ARTISTS Marina Abramović; John Baldessari; Joan Jonas; Damien Hirst; Tino Sehgal; Allora and Calzadilla; Simon Fujiwara; Xavier Le Roy; Laura Lima; Roman Ondak; Santiago Sierra; Xu Zhen; Clark Beaumont FACTS It’s not called 13 Performances because it’s not 13 performances. It’s not called 13 Artists because that would be irritating. It’s not called 13 Sculptures because that would be misleading. Instead it’s called 13 Rooms. – Klaus Biesenbach Exhibitions are fundamentally a medium of social encounter. – Hans Ulrich Obrist 13 Rooms ran for 11 days at Pier 2/3, Walsh Bay, Sydney. The exhibition was originally commissioned as 11 Rooms by Manchester International Festival, the International Arts Festival RUHRTRIENNALE 2012- 2014 and Manchester Art Gallery. In addition to the 12 international artists selected to participate in the project, Australian artist duo Clark Beaumont were invited by the curators to present work in a new thirteenth room. -

Infinite Experience

March, 2015 For immediate release TEMPORARY EXHIBITION Infinite Experience Curator: Agustín Pérez Rubio Artists: Allora & Calzadilla - Diego Bianchi - Elmgreen & Dragset – Dora García - Pierre Huyghe - Roman Ondák - Tino Sehgal - Judi Werthein Level 2. From March 20 to June 8 Opening: Thursday, March 19 In March will open at MALBA Infinite Experience, an exhibition of live works that incites reflection on forms of life as well as art and the museum, The works featured in an event with no precedent at a museum in Latin America consist of constructed situations, live installations, and representations and choreographies created in the first years of the 21st century. Works by eight outstanding artists from Argentina and abroad will be featured in the exhibition: Allora & Calzadilla [Jennifer Allora (Philadelphia, 1974) and Guillermo Calzadilla (Havana, 1971)], Diego Bianchi (Buenos Aires, 1969), Elmgreen & Dragset [Michael Elmgreen (Copenhagen, 1961) and Ingar Dragset (Trondheim, Norway, 1968)], Dora García (Valladolid, Spain, 1965), Pierre Huyghe (Paris, 1962), Roman Ondák (Žilina, Slovakia, 1966), Tino Sehgal (London, 1976; he lives in Berlin), and Judi Werthein (Buenos Aires, 1967; she lives in Miami). This is the first time most of these artists have shown their work in Argentina. The exhibition is born of a question: Is a live museum—where the works act, speak, move about, and live eternally—possible? For Agustín Pérez Rubio, artistic director of MALBA and curator of the exhibition: “The works in Experiencia Infinita are particularly concerned with the idea of the living as work and as a component of a kind of art that ensues not only in time but also in space: experience as journey, different situations that take place one after another,” he explains.