Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mexican Movie Stills, 1937-1985

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft2r29n6mt No online items Guide to the Mexican movie stills, 1937-1985 Processed by Special Collections staff. Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http:/library/stanford.edu/spc/ © 2002 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Guide to the Mexican movie stills, M1049 1 1937-1985 Guide to the Mexican movie stills, 1937-1985 Collection number: M1049 Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California Contact Information Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http:/library/stanford.edu/spc/ Processed by: Special Collections staff Date Completed: 1999 Encoded by: Steven Mandeville-Gamble © 2002 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Mexican movie stills, Date (inclusive): 1937-1985 Collection number: M1049 Extent: 10 linear ft. (7,124 photographs from 606 movies) Repository: Stanford University. Libraries. Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives. Abstract: This collection contains still images from 606 movies from the heyday of the Mexican movie industry. The collection is a rich pictorial resource documenting hundreds of Mexican actors and actresses. Language: English. Access None. Publication Rights Property rights reside with the repository. Literary rights reside with the creators of the documents or their heirs. To obtain permission to publish or reproduce, please contact the Public Services Librarian of the Dept. of Special Collections. Preferred Citation Mexican movie stills. -

Plusinside Senti18 Cmufilmfest15

Pittsburgh Opera stages one of the great war horses 12 PLUSINSIDE SENTI 18 CMU FILM FEST 15 ‘BLOODLINE’ 23 WE-2 +=??B/<C(@ +,B?*(2.)??) & THURSDAY, MARCH 19, 2015 & WWW.POST-GAZETTE.COM Weekend Editor: Scott Mervis How to get listed in the Weekend Guide: Information should be sent to us two weeks prior to publication. [email protected] Send a press release, letter or flier that includes the type of event, date, address, time and phone num- Associate Editor: Karen Carlin ber of venue to: Weekend Guide, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 34 Blvd. of the Allies, Pittsburgh 15222. Or fax THE HOT LIST [email protected] to: 412-263-1313. Sorry, we can’t take listings by phone. Email: [email protected] If you cannot send your event two weeks before publication or have late material to submit, you can post Cover design by Dan Marsula your information directly to the Post-Gazette website at http://events.post-gazette.com. » 10 Music » 14 On the Stage » 15 On Film » 18 On the Table » 23 On the Tube Jeff Mattson of Dark Star City Theatre presents the Review of “Master Review of Senti; Munch Rob Owen reviews the new Orchestra gets on board for comedy “Oblivion” by Carly Builder,”opening CMU’s film goes to Circolo. Netflix drama “Bloodline.” the annual D-Jam show. Mensch. festival; festival schedule. ALL WEEKEND SUNDAY Baroque Coffee House Big Trace Johann Sebastian Bach used to spend his Friday evenings Trace Adkins, who has done many a gig opening for Toby at Zimmermann’s Coffee House in Leipzig, Germany, where he Keith, headlines the Palace Theatre in Greensburg Sunday. -

2015, Volume 8

V O L U M E 8 2015 D E PAUL UNIVERSITY Creating Knowledge THE LAS JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE SCHOLARSHIP CREATING KNOWLEDGE The LAS Journal of Undergraduate Scholarship 2015 EDITOR Warren C. Schultz ART JURORS Adam Schreiber, Coordinator Laura Kina Steve Harp COPY EDITORS Stephanie Klein Rachel Pomeroy Anastasia Sasewich TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 Foreword, by Interim Dean Lucy Rinehart, PhD STUDENT RESEARCH 8 S. Clelia Sweeney Probing the Public Wound: The Serial Killer Character in True- Crime Media (American Studies Program) 18 Claire Potter Key Progressions: An Examination of Current Student Perspectives of Music School (Department of Anthropology) 32 Jeff Gwizdalski Effect of the Affordable Care Act on Insurance Coverage for Young Adults (Department of Economics) 40 Sam Okrasinski “The Difference of Woman’s Destiny”: Female Friendships as the Element of Change in Jane Austen’s Emma (Department of English) 48 Anna Fechtor Les Musulmans LGBTQ en Europe Occidentale : une communauté non reconnue (French Program, Department of Modern Languages) 58 Marc Zaparaniuk Brazil: A Stadium All Its Own (Department of Geography) 68 Erin Clancy Authority in Stone: Forging the New Jerusalem in Ethiopia (Department of the History of Art and Architecture) 76 Kristin Masterson Emmett J. Scott’s “Official History” of the African-American Experience in World War One: Negotiating Race on the National and International Stage (Department of History) 84 Lizbeth Sanchez Heroes and Victims: The Strategic Mobilization of Mothers during the 1980s Contra War (Department -

Drama Drama Documentary

1 Springvale Terrace, W14 0AE Graeme Hayes 37-38 Newman Street, W1T 1QA SENIOR COLOURIST 44-48 Bloomsbury Street WC1B 3QJ Tel: 0207 605 1700 [email protected] Drama The People Next Door 1 x 60’ Raw TV for Channel 4 Enge UKIP the First 100 Days 1 x 60’ Raw TV for Channel 4 COLOURIST Cyberbully 1 x 76’ Raw TV for Channel 4 BAFTA & RTS Nominations Playhouse Presents: Foxtrot 1 x 30’ Sprout Pictures for Sky Arts American Blackout 1 x 90’ Raw TV for NGC US Blackout 1 x 90’ Raw TV for Channel 4 Inspector Morse 6 x 120’ ITV Studios for ITV 3 Poirot’s Christmas 1 x 100’ ITV Studios for ITV 3 The Railway Children 1 x 100’ ITV Studios for ITV 3 Taking the Flak 6 x 60’ BBC Drama for BBC Two My Life as a Popat 14 x 30’ Feelgood Fiction for ITV 1 Suburban Shootout 4 x & 60’ Feelgood Fiction for Channel 5 Slap – Comedy Lab 8 x 30’ World’s End for Channel 4 The Worst Journey in the World 1 x 60’ Tiger Aspect for BBC Four In Deep – Series 3 4 x 60’ Valentine Productions for BBC1 Drama Documentary Nazi Megaweapons Series III 1 x 60’ Darlow Smithson for NGCi Metropolis 1 x 60’ Nutopia for Travel Channel Million Dollar Idea 2 x 60’ Nutopia Hostages 1 x 60’ Al Jazeera Cellblock Sisterhood 3 x 60’ Raw TV Planes That Changed the World 3 x 60’ Arrow Media Nazi Megaweapons Series II 1 x 60’ Darlow Smithson for NGCi Dangerous Persuasions Series II 6 x 60’ Raw TV Love The Way You Lie 6 x 60’ Raw TV Mafia Rules 1 x 60’ Nerd Nazi Megaweapons 5 x 60’ Darlow Smithson for NGCi Breakout Series 2 10 x 60’ Raw TV for NGC Paranormal Witness Series 2 12 x 60’ Raw TV -

Sede Sur Departamento De Investigaciones Educativas

CENTRO DE INVESTIGACIÓN Y DE ESTUDIOS AVANZADOS DEL INSTITUTO POLITÉCNICO NACIONAL SEDE SUR DEPARTAMENTO DE INVESTIGACIONES EDUCATIVAS La evaluación del desempeño docente como política pública y como propuesta de evaluación. Contextos de significación desde las voces de maestros de educación primaria en México Tesis que presenta Lilia Antonio Pérez Para obtener el grado de Doctora en Ciencias En la especialidad de Investigaciones Educativas Directora de Tesis Dra. Rosalba Genoveva Ramírez García Ciudad de México Febrero, 2021 Agradecimientos Para la elaboración de esta tesis, se contó con el apoyo de una beca de Conacyt A Eduardo Weiss, mi maestro, mi cómplice profesional y amigo, gracias por acompañarme en esta aventura intelectual que fructifica en el presente trabajo; gracias porque junto a tus precisiones y enseñanzas, tu sencillez no te impedía ofrecer el elogio, la palabra de aliento genuina, que alimenta no solo al intelecto, sino también al alma. A Rosalba Ramírez, por tu generosidad al retomar la estafeta de este acompañamiento académico, gracias por tu apoyo en el momento en que más lo necesitaba, gracias por los espacios y tiempos brindados, sin ti, la culminación de este itinerario no hubiera sido posible. A María de Ibarrola, Alicia Civera, Alberto Arnaut, Adelina Castañeda, Aurora Loyo, Felipe Martínez Rizo, porque sus valiosos comentarios y sugerencias hicieron posible el enriquecimiento del trayecto recorrido en la elaboración del presente trabajo A los docentes investigadores del Departamento de Investigaciones Educativas, porque sus valiosas enseñanzas me abrieron horizontes de reflexión, por enriquecer mi formación; al personal administrativo y de apoyo por sus orientaciones oportunas, por su calidez humana. -

R E S U L T a N D O

1 TOLUCA DE LERDO, MÉXICO; ONCE DE FEBRERO DOS MIL DIECISEIS. VISTO, para resolver el Toca 27/2016, relativo a la carpeta administrativa 309/2013, radicada en el JUZGADO DE CONTROL DEL DISTRITO JUDICIAL DE LERMA, ESTADO DE MÉXICO en contra de (***), por el hecho delictuoso de ACTOS LIBIDINOSOS en agravio de la sujeto femenino menor de edad de identidad resguardada, en el que seinterpuso el RECURSO DE APELACIÓN en contra del AUTO DE VINCULACIÓN A PROCESO emitido el VEINTICUATRO DE DICIEMBRE DOS MIL QUINCE, y; R E S U L T A N D O 1. El dos de mayo de dos mil quince, se celebró la Audiencia para formulación de imputación por cumplimiento de orden de aprehensión, el Ministerio Público formuló imputación en contra de (***) por el hecho delictuoso de ACTOS LIBIDINOSOS en agravio de sujeto femenino de identidad resguardada (***), después de que la Juzgadora decretara y calificara la detención judicial del justiciable, en su contra, el imputado (***) al encontrarse asistido de su defensor privado formuló su declaración con relación al hecho que se le atribuye y solicito la duplicidad del término constitucional; posteriormente, la Representación Social solicitó su Vinculación a Proceso, dictando la Juez de Control en Audiencia de fecha seis de mayo de dos mil quince, AUTO DE VINCULACIÓN A PROCESO en su contra, por el hecho delictuoso antes señalado, con los siguientes puntos resolutivos: “PRIMERO. Al estimar colmados en la especie las exigencias de los artículos 16 y 19 de la Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, así como en los -

Mujer, Tradición Y Conciencia Histórica En Gertrudis Gómez De Avellaneda

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2017 MUJER, TRADICIÓN Y CONCIENCIA HISTÓRICA EN GERTRUDIS GÓMEZ DE AVELLANEDA Ana Lydia Barrios University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Latin American Literature Commons, and the Spanish Literature Commons Recommended Citation Barrios, Ana Lydia, "MUJER, TRADICIÓN Y CONCIENCIA HISTÓRICA EN GERTRUDIS GÓMEZ DE AVELLANEDA. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/4441 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Ana Lydia Barrios entitled "MUJER, TRADICIÓN Y CONCIENCIA HISTÓRICA EN GERTRUDIS GÓMEZ DE AVELLANEDA." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Modern Foreign Languages. Óscar Rivera-Rodas, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Michael Handelsman, Nuria Cruz-Cámara, Jacqueline Avila Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) MUJER, TRADICIÓN Y CONCIENCIA HISTÓRICA EN GERTRUDIS GÓMEZ DE AVELLANEDA A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Ana Lydia Barrios May 2017 ii Copyright © 2017 by Ana Lydia Barrios All rights reserved. -

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

Revista Nº 27

4 Q ueremos sumarnos al esfuerzo de facilitar, desde la artículos, entrevistas, trabajos,... Algunos de José Heredia; idea de Maiakovski y desde la humildad de nuestra revista, otros, de aquellas personas, periodistas o instituciones que el conocimiento de José Heredia, para que su arte se algo tenían que decir de él. La dificultad de encontrar la expanda y sea un referente, para gitanos y no gitanos, para obra de José Heredia también anima esta publicación. las personas que desde la literatura, el teatro y la poesía abrimos caminos para el conocimiento, para la igualdad, La amistad no necesita justificaciones. Si partimos de una para el valor de los diversos maestros y maestras y de sus amistad de tantísimos años no tiene sentido buscar diversas culturas. justificaciones a esta publicación dedicada a José Heredia. Si alguien cree que la amistad evita o esconde alguna Queremos, desde la vocación y responsabilidad de este mediocridad, aquí se equivoca. Pero si alguien nunca se ha recurso público que es la Revista de la Asociación de acercado a la obra (escrita y vivida) de José Heredia Maya, Enseñantes con Gitanos, recopilar y ofreceros una serie de tendríamos que decirle aunque sea sólo aquello que ya ha 5 Alrededor de José Heredia Maya 6 Alrededor de José Heredia Maya tenido un reconocimiento oficial (La Junta de Andalucía le ayudó al nacimiento del asociacionismo gitano, también a concede el Premio Andaluz Gitano en el año 2000; el nuestro movimiento educativo que con el tiempo nos llevó a Instituto de Cultura Gitana le concede Premio de Cultura constituirnos como la Asociación de Enseñantes con Gitanos. -

C Ntentasia 7-20 March 2016 Page 2

#GreatJobs page 12 & 13 ! s r a ye 2 0 C 016 g 1 NTENT - Celebratin www.contentasia.tv l https://www.facebook.com/contentasia?fref=ts facebook.com/contentasia l @contentasia l www.contentasiasummit.com 7-20 March 2016 Turner shifts creative services MAIN COLOR PALETTE 10 GRADIENT BG GRADIENT R: 190 G: 214 B: 48 to SingaporeR: 0 G: 0 B: 0 Take the green and the blue Take the green and the blue C: 30 M: 0 Y: 100 K: 0 C: 75 M: 68 Y: 67 K: 90 from the main palette. from the main palette. Opacity: 100% Opacity: 50% R: 0 G: 80 B: 255 R: 138 G: 140 B: 143 Blending Mode: Normal Blending Mode: Hue C: 84 M: 68 Y: 0 K: 0 C: 49 M: 39 Y: 38 K: 3 Senior management team will continue to call Hong Kong home Turner is shifting more of its creative services out of Hong Kong to Singapore, expanding its regional presence and taking advantage of new cutting edge technology on offer in Singapore. But there’s no truth to last week’s rumour that the entire operation is shifting out of Hong Kong, Turner execs say. Full story on page 8 India’s soap queen goes over the top Balaji’s Ekta Kapoor all set for OTT debut India’s high-profile TV creator, Ekta Ka- poor, is going full tilt at digital audiences TUESDAYS 9:55PM (8:55PM JKT/BKK) with a new US$23-million purse and her eye on four million SVOD subscribers in the next four years. -

Sunday Morning Grid 1/15/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

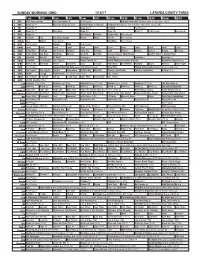

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/15/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Ohio State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Football Night in America Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Kansas City Chiefs. (10:05) (N) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Program Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Planet Weird DIY Sci Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Hubert Baking Mexican 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Miranda Age Fix With Dr. Anthony Youn 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Escape From New York ››› (1981) Kurt Russell. -

Show #1379 --- Week of 6/14/21-6/20/21 HOUR ONE--SEGMENTS 1-3 SONG ARTIST LENGTH ALBUM LABEL___SEGMENT

Show #1379 --- Week of 6/14/21-6/20/21 HOUR ONE--SEGMENTS 1-3 SONG ARTIST LENGTH ALBUM LABEL________________ SEGMENT ONE: "Million Dollar Intro" - Ani DiFranco :55 in-studio n/a "Big Things"-Ted Hawkins 2:45 The Next Hundred Years DGC "Two Step Down To Texas"-Ingram/Lambert/Randall 2:30 The Marfa Tapes RCA "Be Good"-Carsie Blanton 3:30 Love & Rage independent "I’ll Be Your Girl"-The Decemberists 2:35 I’ll Be Your Girl Capitol "Avant Gardener"-Courtney Barnett (in-studio) 3:50 in-studio n/a ***MUSIC OUT AND INTO: ***NATIONAL SPONSOR BREAK*** Nettwerk Records/Old Sea Brigade "Motivational Speaking" (:30) Outcue: " OldSeaBrigade.com." TOTAL TRACK TIME: 19:18 ***PLAY CUSTOMIZED STATION ID INTO: SEGMENT TWO: "Hope"-Arlo Parks (in-studio) 4:30 in-studio n/a ***INTERVIEW & MUSIC: ROSTAM (in California) ("Changephobia," "These Kids We Knew") in-studio interview/performance n/a ***MUSIC OUT AND INTO: ***NATIONAL SPONSOR BREAK*** Leon Speakers/"The Leon Loft" (:30) Outcue: " at LeonSpeakers.com." The Ark/"COVID-19 Slow Return 1" (:30) Outcue: " TheArk.org." TOTAL TRACK TIME: 21:22 SEGMENT THREE: "I Disappear"-Matt The Electrician (SongWriter) 4:30 in-studio independent "Stay Alive"-Mustafa 3:00 When Smoke Rises Young Turks "Know You Got To Run"-Stephen Stills 4:10 Déjà Vu Rhino ***MUSIC OUT AND INTO: ***NATIONAL SPONSOR BREAK*** Nettwerk Records/Beta Radio "Year Of Love" (:30) Outcue: " BetaRadio.com." TOTAL TRACK TIME: 14:19 TOTAL TIME FOR HOUR ONE-54:59 acoustic café · p.o. box 7730 · ann arbor, mi 48107-7730 · 734/761-2043 · fax 734/761-4412