Technologies of Accident: Forensic Media, Crash Analysis, and the Redefinition of Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drama Drama Documentary

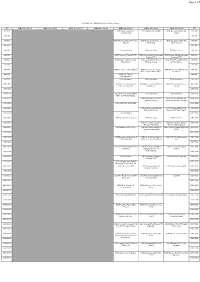

1 Springvale Terrace, W14 0AE Graeme Hayes 37-38 Newman Street, W1T 1QA SENIOR COLOURIST 44-48 Bloomsbury Street WC1B 3QJ Tel: 0207 605 1700 [email protected] Drama The People Next Door 1 x 60’ Raw TV for Channel 4 Enge UKIP the First 100 Days 1 x 60’ Raw TV for Channel 4 COLOURIST Cyberbully 1 x 76’ Raw TV for Channel 4 BAFTA & RTS Nominations Playhouse Presents: Foxtrot 1 x 30’ Sprout Pictures for Sky Arts American Blackout 1 x 90’ Raw TV for NGC US Blackout 1 x 90’ Raw TV for Channel 4 Inspector Morse 6 x 120’ ITV Studios for ITV 3 Poirot’s Christmas 1 x 100’ ITV Studios for ITV 3 The Railway Children 1 x 100’ ITV Studios for ITV 3 Taking the Flak 6 x 60’ BBC Drama for BBC Two My Life as a Popat 14 x 30’ Feelgood Fiction for ITV 1 Suburban Shootout 4 x & 60’ Feelgood Fiction for Channel 5 Slap – Comedy Lab 8 x 30’ World’s End for Channel 4 The Worst Journey in the World 1 x 60’ Tiger Aspect for BBC Four In Deep – Series 3 4 x 60’ Valentine Productions for BBC1 Drama Documentary Nazi Megaweapons Series III 1 x 60’ Darlow Smithson for NGCi Metropolis 1 x 60’ Nutopia for Travel Channel Million Dollar Idea 2 x 60’ Nutopia Hostages 1 x 60’ Al Jazeera Cellblock Sisterhood 3 x 60’ Raw TV Planes That Changed the World 3 x 60’ Arrow Media Nazi Megaweapons Series II 1 x 60’ Darlow Smithson for NGCi Dangerous Persuasions Series II 6 x 60’ Raw TV Love The Way You Lie 6 x 60’ Raw TV Mafia Rules 1 x 60’ Nerd Nazi Megaweapons 5 x 60’ Darlow Smithson for NGCi Breakout Series 2 10 x 60’ Raw TV for NGC Paranormal Witness Series 2 12 x 60’ Raw TV -

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

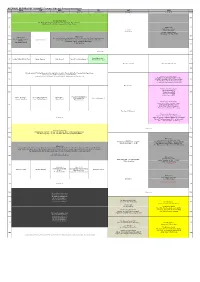

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfihn master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality o f the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zed) Road, Ann Arbor Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/76M700 800/521-0600 THE WRITING OF CRISTINA PACHECO: NARRATING THE MEXICAN URBAN EXPERIENCE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dawn Slack, M.A. -

And Inter-Organizational Risk Information Transmission Before and During Major Disasters

Research Collection Doctoral Thesis Causes of Failures in Intra- and Inter-organizational Risk Information Transmission Before and During Major Disasters. Sector Differences in Risk Management Author(s): Chernov, Dmitry Publication Date: 2015 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-a-010578894 Rights / License: In Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Permitted This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library Diss.-No. ETH 23097 Causes of Failures in Intra- and Inter-organizational Risk Information Transmission Before and During Major Disasters. Sector Differences in Risk Management A thesis submitted to attain the degree of DOCTOR OF SCIENCES of ETH ZURICH (Dr. sc. ETH Zurich) presented by DMITRY CHERNOV Candidate of economics science (specialization – management), State University of Management (Moscow, Russia) born on January 6th 1980 Citizen of Russian Federation accepted on the recommendation of Prof. Dr. Didier Sornette ETH Zurich Examiner Prof. Dr. Yossi Sheffi MIT Co-examiner Prof. Dr. Ulrich Alois Weidmann ETH Zurich Co-examiner Prof. Dr. Antoine Bommier ETH Zurich President of the committee 2015 I “Science is the systematic classification of experience” George Henry Lewes (1817-78), English writer and critic. “The origin of science is in the desire to know causes; and the origin of all false science and imposture is in the desire to accept false causes rather than none; or, which is the same thing, in the unwillingness to acknowledge our own ignorance” William Hazlitt (1778-1830) English essayist. “If reality disagrees with theory, reality wins. Always. That's science” Richard Feynman (1918-1988), Nobel Prize laureate in Physics, member of The Rogers Commission Report, which was created to investigate the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my very great appreciation to Prof. -

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC Program Schedule March

Page 1 of 5 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC Program Schedule March (ET) 月曜日 2019/02/25 火曜日 2019/02/26 水曜日 2019/02/27 木曜日 2019/02/28 金曜日 2019/03/01 土曜日 2019/03/02 日曜日 2019/03/03 (ET) 400-430 04:00 Mega Breakdown 4 04:00 Headhunters of WWII 04:00 Apocalypse World War 400-430 「Phantom Jet」 I[Rage] 430-500 430-500 500-530 05:00 Wild Case Files 2[#1 Poison 05:00 Elemental: Hydrogen vs. 05:00 Apocalypse World War 500-530 Beach] Hindenburg I[Deliverance] 530-600 530-600 600-630 06:00 information 06:00 information 06:00 information 600-630 630-700 06:30 Science of Stupid 2[#6] 06:30 Access 360 World Heritage 06:30 Access 360 World Heritage 630-700 Cutdowns[#11] Cutdowns[#12] 700-730 07:00 Planet Carnivore「Great 07:00 Cesar To The Rescue 07:00 Wicked Tuna 7[#5 Smoke 700-730 White Shark」 III[Panic Attack] On The Water] 730-800 730-800 800-830 08:00 Two Tales of China[Music] 08:00 Cesar To The Rescue 08:00 Wicked Tuna 7[#6 Two For 800-830 III[The Trouble With Truffles] The Money] 830-900 08:30 Two Tales of 830-900 China[Noodles] 900-930 09:00 information 09:00 information 09:00 information 900-930 930-1000 09:30 Air Crash Investigation 09:30 World's Deadliest[Ultimate 09:30 Wild Australia[Jurassic 930-1000 10[Fire In The Hold] Predators] Jungle] 1000-1030 1000-1030 1030-1100 10:30 Heroes of the Long Road 10:30 information 10:30 information 1030-1100 Home with Martha Raddatz 1100-1130 11:00 Unlikely Animal Friends 11:00 The Incredible Dr. -

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC Program Schedule February(Weekly) MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 6.13.20.27 7.14.21.28 1.8.15.22 2.9.16.23 3.10.17.24 4.11.18.25 5.12.19.26

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC Program Schedule February(weekly) MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 6.13.20.27 7.14.21.28 1.8.15.22 2.9.16.23 3.10.17.24 4.11.18.25 5.12.19.26 400 400 Banged Up Abroad 4、 Nazi Death Camp: The Great Escape Apocalypse WWI: Verdun、 Hitler's Secret Attack →Legion(11th ~5:15)、 →Inside 2 Lockdown: Scam City、 WW2 Hell Under the Sea Wwii's Greatest Raids On America、 No Man Left Behind →JFK: The Lost Bullet →Next Megaquake(19th ~6:00) Inside the FBI Nazi World War Weird →Killing Reagan(26th ~6:00) 430 430 500 500 Return From The Dead Mystery Caves of Guangxi 、Blood Antiquities、Light The Ocean、Invasion Earth、Seas Strangest Square Mile、 Dark Secrets of The Lusitania →Before Mars China's Ghost Army、Lost Continent of The Pacific、Russia's Mystery Files 、Crime Lab、Inside: The Mob Squad →Sex In The Stone Age →Crime Lab 530 530 600 information 600 Do Or Die、 CRITTERCAM、 Monster Jellyfish(4th ~7:30) None of The Above 630 Science of Stupid None of The Above Science of Stupid Series 2 630 Mad Scientists Is It Real? →CROC CHRONICLES →Abandoned 700 700 None of The Above Highway Thru Hell Season 4(4th ~8:30) Cesar Millan's →How To Win At Everything Animal ER Animals Gone Wild 3 Savage Kingdom America's National Parks →Squid vs. Whale Leader of The Pack →Legion(12th ~8:15) →Shark Men →Live Free or Die 730 730 800 800 Four Mums In A Boat、 Wingsuit Daredevil、 Fidel Castro: The Lost Tapes、 Big, Bigger, Biggest 2、 4 Babies A Second Border Wars Compilation: Lawless Island、 Seconds From Disaster (Reversion)(4th 8:30~) Airport Security: Colombia The Great -

The Nominations

NOMINEES FOR THE NEWS AND DOCUMENTARY EMMY AWARDS ANNOUNCED BY THE NATIONAL TELEVISION ACADEMY Ceremony to be Held September 25 in New York City New York, N.Y. – July 18, 2006 (revised 11/07/06) – Nominations for the 27th Annual News and Documentary Emmy Awards were announced today by the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. The News and Documentary Emmy Awards will be presented on Monday, September 25 at a black-tie ceremony at the Marriott Marquis Hotel in New York City, attended by more than 700 television and new media industry executives, news and documentary producers and journalists. Sponsors for the 27th Annual News & Documentary Emmy Awards include Grass Valley, a Thomson brand, and Television Week, the print partner. “This year’s nominees have done an exceptional job of covering the major stories of the day – from the war zones around the world to the devastation of Hurricane Katrina,” said Peter Price, President/CEO, National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. “They also shed light on serious social concerns, such as the growing number of Americans without health insurance. The quality and breadth of the reporting in this year’s nominees are exceptional.” "This year's nominations are exceptionally fine," said Bill Small, Chairman of News and Documentary Emmy Awards. "Their high quality – as good as we’ve seen in years -- is especially reflected in the large number of nominations for Hurricane Katrina coverage and aspects of the war in Iraq." The numerical breakdown, by broadcast and cable entities, as compiled -

Ng Dark 00:55 00:55

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC - BULGARIA APRIL MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 06:00 WILD CHRONICLES -> 11.04 DO OR DIE 06:00 06:20 I DIDN'T KNOW THAT 3 -> 06.04 STREET GENIUS 06:20 06:45 DANGER DECODED -> 13.04 SCIENCE OF STUPID 06:45 07:10 HIGHWAY THRU HELL: USA -> THE INCREDIBLE DR. POL 1 & 2 07:10 LAWLESS ISLAND 1 & 2 08:05 DEAD END EXPRESS -> 13.04 ALASKA WING MEN 1 & 2 08:05 09:00 BIG FISH TEXAS -> 20.04 BIG FIX ALASKA 09:00 09:30 BANGED UP ABROAD THE INCREDIBLE DR. POL 09:30 10:00 6 & 7 1 & 2 10:00 11:00 SECONDS FROM DISASTER 6 - > 10.04 AIR CRASH INVESTIAGATION DANGER DECODED -> 22.04 11:00 11:30 DANGEROUS ENCOUNTERS ACCESS 360 WORLD 11:30 12:00 URBAN JUNGLE - > 10.04 AIR CRASH INVESTIAGATION 12:00 12:30 12:30 13:00 NAZI MEGASTRUCTURES 13:00 13:30 13:30 14:00 BIG, BIGGER, BIGGEST 3 -> 04.04 ENGINEERING CONNECTIONS -> 27.04 MEGA BREAKDOWN 14:00 14:30 ICE ROAD RESCUE 14:30 15:00 HIGHWAY THRU HELL 2 -> 22.04 WORLD'S 15:00 16:00 HIGHWAY THRU HELL DOOMSDAY TOUGHEST FIXES 16:00 PREPPERS 2 17:00 ALASKA WING MEN 1 & 2 -> 26.04 YUKON GOLD 1 17:00 18:00 BIG FISH TEXAS -> 13.04 BIG FIX ALASKA -> 25.04 COLD WATER GOLD 18:00 19:00 19:00 20:00 20:00 ACI 16 -> 17.04 MARS RT -> 26.04 STRIPPERS: CARS FOR 20:55 ORIGINS RT CAR SOS 5 CASH RT-> 14.04 ORIGINS 20:55 PARCHED GENIUS MEGASTRUCTURES RT EARTH WEEK AIR CRASH SPECIALS -> 12.04 GEN X -> 09.04 HISTORY'S SCIENCE OF EASTER -> 22.04 21:55 CRIME LAB INVESTIGATION 15 CAR SOS 5 RT WATER & POWER: 21:55 SECRETS 2 STUPID 4 EARTH DAY -> 29.04 RT CALIFORNIA HEIST -> YEARS OF LIVING DEATH OF HITLER LAWLESS OCEANS -> 10.04 DRUGS INC. -

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL Program Schedule

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL Program Schedule September(easiness) MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 7.14.21.28 1.8.15.22.29 2.9.16.23.30 3.10.17.24 4.11.18.25 5.12.19.26 6.13.20.27 400 400 NATGEO WILD HOUR Wild Mississippi、Hunt for the Shadow Cat、Superpride、Shane Untamed、 Wild Russia、The Wild West、Sumatra's Last Tiger、Zambezi 430 Military Hour 430 Wwii's Greatest Raids Car SOS →Nazi Underworld →Car Sos II →Inside Combat Rescue →Apocalypse: The Rise of Hitler 500 500 Military Hour Military Hour Apocalypse: The Second World War、Inside: Cocaine Sub Hunt、Titanic's Nuclear Secret、 Hitler's Secret Attack On Top Gear Season3 Inside: Afghan Marine Base、Attack of The Zeppelins、Inside:Iraq's Kill Zone、 America、 Inside:Super Carrier、Apocalypse World War I、 Nazi Megastructures D-Day Sacrifice 530 530 600 information 600 Grand Mama's Boy 、 630 The Big Picture With Kal Penn Danger Decoded Brain Games 2 None of The Above Season 2 630 The Wine Quest: Spain Top Gear Season3 Top Gear USA Season4 700 700 Maya Underworld: The Real Doomsday、Evacuate Earth、Ancient X-Files 2、Sailing The Treasure Ship、Mega Quake、 Space Crab、Secret Bible、Saving Egypt's Oldest Pyramid、 Trekking the Great Wall、Egypt Underworld、Eclipse、Humpbacks: Cracking The Code Entertain Your Brain Special The Big Picture With Kal Penn[Crime, Inc.] 730 /The Big Picture With Kal Penn[Treasure Hunt] 730 /The Big Picture With Kal Penn[Sex Drive] /The Big Picture With Kal Penn[Going Viral] Megafactories Entertain Your Brain Special Danger Decoded[#7] 800 /Danger Decoded[#8] 800 /Danger Decoded[#9] /Danger -

C NTENTASIA See Page 4

The Job Space The place to look for the jobs that count C NTENTASIA See page 4 www.contentasia.tv Issue 95: April 26-May 9, 2010 Strong pay-TV prospects June rollout for Food Network Asia in Asia-Pac, MPA Scripps ramps up local content acquisitions India’s pay-TV market is Scripps Networks International poised for long-term profitable is rumoured to be prepping for growth as media owners and a 1 June rollout of its HD Food atiger’seyes distributors expand market Network in Asia. share “with an eye on profits The Food Network Asia will de- What’s really going on rather than at the expense of but in at least two markets, and out there... profits”, Media Partners Asia’s possibly four. These almost certain- (MPA) new report, Asia Pacific ly include Singapore and Taiwan, Pay-TV & Broadband Markets Food, glorious food… with best bets that the other two and this year’s MIPTV 2010, says. will be Malaysia and Korea. But regulation, “which had a higher focus than ever Scripps has not confirmed the – both on and off screen – on continues to commoditise launches, saying the announce- and destroy industry value,” all things edible. ments will come from its carriage At the top of our culinary remains a major threat to partners. growth assumptions for India, fabulosity list this year are Meanwhile, the network has Scripps, AETN and Fremantle- a country poised to become picked up season one of Aussie the largest direct-broadcast Media. cooking show, Luke Nguyen’s And then there was Japa- market on earth in two years Vietnam, from SBS Australia for time, MPA says. -

NGC Japan -January 2011

NGC Japan -January 2011 MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 3.10.17.24.31 4.11.18.25 5.12.19.26 6.13.20.27 7.14.21.28 1.8.15.22.29 2.9.16.23.30 Unbelievable Hour 400 Known Universe 400 Banged Up Abroad 4、Amazing Moments 2、Inside: Afghan ER、Seconds from Disaster 3、 Known Universe → Don't Tell My Mother 2、Mega Breakdown 2、 Great Migrations 430 Air Crash Investigation 6 430 Past disaster TOP5(4th~10th) Gulf Coast Disaster、Naked Science : Iceland Volcano、My 9/11、Trapped、Seconds from Disaster 3 500 500 Future Scenario TOP5(11th~17th) 2012: The Final Prophecy、Naked Science 7、Naked Science 5、Is It Real 2、 2210: The Collapse?(~7:00) Space Special(18th~24th) Wild (R) Engineering Connections、Alien Worlds、Martian Robots、Eclipse、Living on Mars 530 530 Car Special Mega Factories 2、Inside Jaguar 600 Nat Geo Amazing!、 Known Universe、 Apocalypse: The Second World War、 600 Lockdown III、Predator CSI 2 630 630 700 Nat Geo Adventure 700 Long Way Down、World's most Dangerous Drug、Japanese Cowboy、 Nat Geo Amazing! Inside Jerusalem's Holiest、Titanic's Nuclear Secret、Nomads Ski Japan、 730 Boxing Behind Bars、 Crystal Skulls、Dive Detectives、Inside Nirvana 730 New Year SP 1 2 AMERICA'S Sumo Kids DEADLY OBSESSION: Breakout SP 15 SNAKES 800 Breakout 800 「Pittsburgh Six」 Hollywood Voice- over Special 16 Air Crash Eye of the Investigation SP Leopard(~10:00) Science Hour 22 World's Toughest Fixes 2、Naked Science 7、Megastructures:UK Super Train Air Crash Investig Caught in the Act ation 4「Miracle SP 23 Escape」 Caught In The Act 3「#1」 830 29 Bible's Buried 830 Secrets#1 Trapped -

Nat Geo SEA Program Listing for May 2012 Released on 15 May 2012

Nat Geo SEA Program Listing For May 2012 Released On 15 May 2012 Release On 2012-05-15 12:13:16 HK Time on Tue 01 May 00:00 Drugs Inc. - Cannabis - 4 01:00 Drugs Inc. - Methamphetamine - 2 02:00 D-Day: Men And Machines - Ep 2 - 2 03:00 The Bombing of Germany 04:00 Helicopter Wars - Vietnam Firefight - 3 05:00 Drugs Inc. - Cannabis - 4 06:00 D-Day: Men And Machines - Ep 2 - 2 07:00 The Bombing of Germany 07:55 Helicopter Wars - Vietnam Firefight - 3 08:50 D-Day: Men And Machines - Ep 2 - 2 09:45 Departures - Sri Lanka S3 - 3 10:40 Don't Tell My Mother - Mexico City S3 - 5 11:05 Don't Tell My Mother - Sao Paolo S3 - 6 11:35 Seconds From Disaster - Chicago Air Crash S3 - 6 12:30 Most Amazing Moments - Most Thrilling Moments - 4 13:25 Food Lover's Guide To The Planet - India - 1 13:50 Food Lover's Guide To The Planet - The Spice Road S2 - 2 14:20 Korean Soul Food 15:15 Dog Whisperer - Willie, Make-A-Wish And Zena S4 - 4 16:10 Dog Whisperer - Whipped & Wild S4 - 20 17:05 Dog Whisperer - Fear of Dogs S4 - 25 18:00 Monster Fish - Mongolian Terror Trout - 1 19:00 Seconds From Disaster - Chicago Air Crash S3 - 6 20:00 Locked Up Abroad - Bangkok Underworld S5 - 1 21:00 Rock Stars - Man V. Boulder - 8 22:00 Forensic Firsts (AKA Crime Lab) - DNA Profiling - 1 23:00 Locked Up Abroad - The Philippines S3 - 7 HK Time on Wed 02 May 00:00 Rock Stars - Man V.