A Comparative Investigation of the Concept of Nature in the Writings of Henry M. Morris and Bernard L. Ramm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ron Numbers Collection-- the Creationists

Register of the Ron Numbers Collection-- The Creationists Collection 178 Center for Adventist Research James White Library Andrews University Berrien Springs, Michigan 49104-1400 1992, revised 2007 Ron Numbers Collection--The Creationists (Collection 178) Scope and Content This collection contains the records used as resource material for the production of Dr. Numbers' book, The Creationists, published in 1992. This book documents the development of the creationist movement in the face of the growing tide of evolution. The bulk of the collection dates from the 20th century and covers most of the prominent, individual creationists and pro-creation groups of the late 19th and 20th century primarily in the United States, and secondarily, those in England, Australia, and Canada. Among the types of records included are photocopies of articles and other publications, theses, interview tapes and transcripts, and official publications of various denominations. One of the more valuable contributions of this collection is the large quantity of correspondence of prominent individuals. These records are all photocopies. A large section contains documentation related to Seventh-day Adventist creationists. Adventists were some of the leading figures in the creationist movement, and foremost among this group is George McCready Price. The Adventist Heritage Center holds a Price collection. The Numbers collection contributes additional correspondence and other documentation related to Price. Arrangement Ron Numbers organized this collection for the purpose of preparing his book manuscript, though the book itself is not organized in this way. Dr. Numbers suggested his original arrangement be retained. While the collection is arranged in its original order, the outline that follows may be of help to some researchers. -

PSCF09-16P155-164Kim New Pic.Indd

Article Bernard Ramm’s Scientifi c Approach to Theology Andrew Kim Andrew Kim The year 2016, which marks the 75th anniversary of the American Scientifi c Affi liation, also marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Bernard L. Ramm (1916–1992), one of the affi liation’s most important fi gures, and one whose infl uence among evangelicals in the area of religion and science has been matched by few others. Much of the historical attention given to Ramm has focused on his scientifi c background and how it infl uenced his biblical hermeneutic and treatment of scientifi c topics. However, through use of hitherto unstudied sources, this article will show how his scientifi c background also conditioned his overarching theological method. By building on ideas rooted in orthodoxy and history, openly accepting new data and evidence into his system, and adjusting his ideas to compensate for changes and developments, Ramm exhibited a scientifi c methodology that undergirded the development, change, and growth of his theology throughout his career. s news of the gravitational in turn, made the recent discovery pos- wave readings at the Laser sible.2 In other words, Einstein’s scientifi c A Interferometer Gravitational- approach not only retained original ideas Wave Observatory (LIGO) was publicly but also left room for reconsideration, announced on February 11, 2016, excite- revision, and review, which allowed for ment rippled through the scientifi c further contribution and development. community. The LIGO data supplied evidence for theories of space-time and Born in the same year that Einstein gave gravitational waves postulated by Albert birth to his gravitational wave theory Einstein in 1916 and confi rmed “Einstein’s was a quiet and unassuming American theory of gravity, the general theory of Baptist theologian named Bernard Ramm relativity, with unprecedented rigor and (1916–1992). -

INTEGRITY a Lournøl of Christiøn Thought

INTEGRITY A lournøl of Christiøn Thought PLTBLISHED BY THE COMMISSION FOR THEOLOGICAL INTEGRITY OF THE NAIIONALASSOCIATION OF FREE WILLBAPTISTS Editor Paul V. Harrison Pastoq Cross Timbers Free Will Baptist Church Assistønt Editor Robert E. Picirilli Professor Emeritus, Free Will Baptist Bible College Editorøl Board Tim Eatoru Vice-President, Hillsdale Free Will Baptist College Daryl W Ellis, Pastor, Butterfield Free Wilt Baptist Church, Aurora, Illinois Keith Fletcheq Editor-in-Chief Randall House Publications F. Leroy Forlines, Professor Emeritus, Free Will Baptist Bible College Jeff Manning, Pastor, Unity Free Will Baptist Church, Greenville, North Carolina Garnett Reid, Professo¡, Free Will Baptist Bible College Integrity: A Journøl of Chrístian Thought is published in cooperation with Randall House Publications, Free Will Baptist Bible College, and Hillsdale Free Will Baptist College. It is partially funded by those institutions and a number of interested churches and individuals. Integrity exists to stimulate and provide a forum for Christian scholarship among Free Will Baptists and to fulfill the purposes of the Commission for Theological Integrity. The Commission for Theological Integrity consists of the following members: F. Leroy Forlines (chairman), Dãryl W. Ellis, Paul V. Harisory Jeff Manning, and J. Matthew Pinson. Manuscripts for publication and communications on editorial matters should be directed to the attention of the editor at the following address: 866 Highland Crest Drive, Nashville, Tennessee 37205. E-rnall inquiries should be addressed to: [email protected]. Additional copies of the journal can be requested for $6.00 (cost includes shipping). Typeset by Henrietta Brozon Printed by Randøll House Publications, Nashaille, Tennessee 37217 OCopyright 2003 by the Comrnission for Theological Integrity, National Association of Free Will Baptists Printed in the United States of America Contents Introduction .......7-9 PAULV. -

2009-10 Academic Catalog

catalog 2009/10 admissions office 800.600.1212 [email protected] www.gordonconwell.edu/charlotte/admissions 14542 Choate Circle, Charlotte, NC 28273 704.527.9909 ~ www.gordonconwell.edu Contents CATALOG 2009/10 GORDON-CONWELL THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY–CHARLOTTE 1 Introduction 37 Degree Programs 3 History and Accreditation 40 Master of Divinity 4 President’s Message 41 Master of Arts 6 Our Vision and Mission 43 Master of Arts in Religion 8 Statement of Faith 43 Doctor of Ministry 10 Community Life Statement 46 Checksheets 11 Faculty 58 Seminary Resources 25 Board of Trustees 59 The Harold John Ockenga Institute 25 Emeriti 59 Semlink 64 Campus Ethos and Resources 26 Admissions 69 Associated Study Opportunities 28 Tuition Charges 29 Financial Assistance 71 Course Descriptions 35 Other Campuses 72 Division of Biblical Studies 77 Division of Christian Thought 80 Division of the Ministry of the Church 85 Calendar 2009-2010 2 introduction history Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary has a rich heritage, spanning more than a century. The school’s roots are found in two institutions which have long provided evangelical leadership for the Christian church in a variety of ministries. The Conwell School of Theology was founded in Philadelphia in 1884 by the Rev. Russell Conwell, a prominent Baptist minister. In 1889, out of a desire to equip “men and women in practical religious work... and to furnish them with a thoroughly biblical training,” the Boston Missionary Training School was founded by another prominent Baptist minister, the Rev. Adoniram J. Gordon. The Conwell School of Theology and Gordon Divinity School merged in 1969 through the efforts of philanthropist J. -

Burdick, Clifford Leslie (1894–1992)

Burdick, Clifford Leslie (1894–1992) JAMES L. HAYWARD James L. Hayward, Ph.D. (Washington State University), is a professor emeritus of biology at Andrews University where he taught for 30 years. He is widely published in literature dealing with ornithology, behavioral ecology, and paleontology, and has contributed numerous articles to Adventist publications. His book, The Creation-Evolution Controversy: An Annotated Bibliography (Scarecrow Press, 1998), won a Choice award from the American Library Association. He also edited Creation Reconsidered (Association of Adventist Forums, 2000). Clifford Leslie Burdick, a Seventh-day Adventist consulting geologist, was an outspoken defender of young earth creationism and involved in the search for Noah’s Ark. Many of his claims were sensationalist and later discredited. Early Life and Education Born in 1894, Burdick was a graduate of the Seventh Day Baptist Milton College of Wisconsin. After accepting the Seventh-day Adventist message, Burdick enrolled at Emmanuel Missionary College (EMC, now Andrews University) in hopes of becoming a missionary. There he met the prominent creationist George McCready Price who inspired Burdick’s Clifford Leslie Burdick. interest in “Flood geology.”1 From Youth's Instructor, July 11, 1967 In 1922 Burdick submitted a thesis to EMC entitled “The Sabbath: Its Development in America,” which he later claimed earned him a Master of Arts degree in theology. Records show, however, that he never received a degree at EMC. He also claimed to have received a master’s degree in geology from the University of Wisconsin. Although he did complete several courses in geology there, he failed his oral exams and thus was denied a degree.2 During the 1950s Burdick took courses in geology and paleontology at the University of Arizona with plans to earn a PhD. -

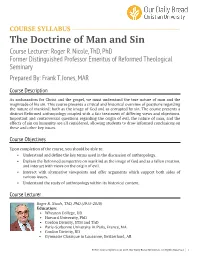

The Doctrine of Man and Sin Course Lecturer: Roger R

COURSE SYLLABUS The Doctrine of Man and Sin Course Lecturer: Roger R. Nicole, ThD, PhD Former Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Reformed Theological Seminary Prepared By: Frank T. Jones, MAR Course Description As ambassadors for Christ and the gospel, we must understand the true nature of man and the magnitude of his sin. This course presents a critical and historical overview of positions regarding the nature of mankind: both as the image of God and as corrupted by sin. The course presents a distinct Reformed anthropology coupled with a fair treatment of differing views and objections. Important and controversial questions regarding the origin of evil, the nature of man, and the effects of sin on humanity are all considered, allowing students to draw informed conclusions on these and other key issues. Course Objectives Upon completion of the course, you should be able to: • Understand and define the key terms used in the discussion of anthropology. • Explain the Reformed perspective on mankind as the image of God and as a fallen creation, and interact with views on the origin of evil. • Interact with alternative viewpoints and offer arguments which support both sides of various issues. • Understand the study of anthropology within its historical context. Course Lecturer Roger R. Nicole, ThD, PhD (1915-2010) Education: • Wheaton College, DD • Harvard University, PhD • Gordon Divinity, STM and ThD • Paris-Sorbonne University in Paris, France, MA • Gordon Divinity, BD • Gymnasie Classique in Lausanne, Switzerland, AB ST504 Course Syllabus -

Price, George Mccready (1870–1963)

Price, George McCready (1870–1963) JAMES L. HAYWARD James L. Hayward, Ph.D. (Washington State University), is a professor emeritus of biology at Andrews University where he taught for 30 years. He is widely published in literature dealing with ornithology, behavioral ecology, and paleontology, and has contributed numerous articles to Adventist publications. His book, The Creation-Evolution Controversy: An Annotated Bibliography (Scarecrow Press, 1998), won a Choice award from the American Library Association. He also edited Creation Reconsidered (Association of Adventist Forums, 2000). George Edward (McCready) Price was a Canadian writer and educator who served in a variety of capacities within the Seventh-day Adventist Church. During the early twentieth century he taught in several secondary schools and denominational colleges. His most enduring legacy, however, is his defense of Flood geology and creationism—he authored two dozen books and hundreds of articles on the topic. He often is credited with founding the modern creationist movement. Early Life and Education George Edward Price (later George McCready Price) was born on August 26, 1870, in Havelock, New Brunswick. His father, George Marshall Price, a nominal Anglican, had established a homestead, George McCready Price. Butternut Ridge, where he farmed newly cleared land. Photo courtesy of the General Conference of Seventh-day He and his first wife bore nine children. After she died, Adventists Archives. he married a tiny woman, Susan McCready, the mother of young George Edward and his younger brother, Charles Luther, born in 1872. The senior Price was not an overly religious man, but he enjoyed listening to Susan read from the Bible each morning.1 Susan McCready Price came from a literary family, including relatives who were newspaper editors in Saint John and Fredericton, New Brunswick. -

Seventh-Day Adventist Professional Organizations

~ of 1978 Annual CDunci1 SDA Profi ional ® _® ons A Quarterly Journal of the Association of Adventist Forums Volume 9, Number 4 A tury of A jJ • r' •onism 1978 GeOscience Field CDnference --- - -~---.--- __ __ E-__ o---,t4---- ~ ~ -- ----~~:~#']Dld------+~e ---~u:jJ "--F~~~rl---1~ Genesis 1 as Theo1CW SPECTRUM EDITOR Gary Land Eric Anderson Margaret McFarland History History Urban Planner Roy Branson Andrews University Pacific Union College Toledo, Ohio Ro berta J. Moore Raymond Cottrell LaVonne Neff EXECUTIVE EDITOR Journalism Theology Author Richard Emmerson Loma Linda University Loma Linda, California College Place, Washington Charles Scriven' Helen Evans Ronald Numbers EDITORIAL BOARD Theology Academic Dean History of Medicine Graduate Theological Union Southwestern Adventist College University of Wisconsin Roy Branson Ethics, Kennedy Institute Ottilie Stafford Judith Folkenberg MelvinK. H. Peters Georgetown University English Researcher Old Testament Atlantic Union College Washington, D.C. Cleveland State University Molleurus Couperus Physician Lawrence Geraty Edward E. Robinson Angwin, California EDITORIAL Old Testament Attorney SDA Theological Seminary Chicago, Illinois Tom Dybdahl ASSISTANT Fritz Guy Gerhard Svrcek-Seiler Journalism Nola-Jean Bamberry United States Congress Theology Psychiatrist SDA Theological Seminary Vienna, Austria Richard Emmerson English CONSULTING Jorgen Henrikson Betty Stirling Walla Walla College Artist Board of Higher Education EDITORS Boston, Massachusetts General Conference ofSDA Alvin L. K wiram Kjeld Andersen Eric A. Magnusson Chemistry Physician L. E. Trader University of Washington Lystrup, Denmark President Education Avondale College, Australia Marienhoehe Gymnasium, W.Germany Association ofAdventist Fonuns EXECUTIVE Of International Relations Corresponding Secretary Lake Molleurus Coupeurus Sean McCarthy Walter Douglas COMMITTEE Physician Undergraduate Church History President Angwin, California Columbia Union College SDA Theological Seminary Glenn E. -

ABSTRACT Reclaiming Peace: Evangelical Scientists And

ABSTRACT Reclaiming Peace: Evangelical Scientists and Evolution After World War II Christopher M. Rios, Ph.D. Advisor: William L. Pitts, Jr., Ph.D. This dissertation argues that during the same period in which antievolutionism became a movement within American evangelicalism, two key groups of evangelical scientists attempted to initiate a countervailing trend. The American Scientific Affiliation was founded in 1941 at the encouragement of William Houghton, president of Moody Bible Institute. The Research Scientists‘ Christian Fellowship was started in London in 1944 as one of the graduate fellowship groups of Inter-Varsity Fellowship. Both organizations were established out of concern for the apparent threat stemming from contemporary science and with a desire to demonstrate the compatibility of Christian faith and science. Yet the assumptions of the respective founders and the context within which the organizations developed were notably different. At the start, the Americans assumed that reconciliation between the Bible and evolution required the latter to be proven untrue. The British never doubted the validity of evolutionary theory and were convinced from the beginning that conflict stemmed not from the teachings of science or the Bible, but from the perspectives and biases with which one approached the issues. Nevertheless, by the mid 1980s these groups became more similar than they were different. As the ASA gradually accepted evolution and developed convictions similar to those of their British counterpart, the RSCF began to experience antievolutionary resistance with greater force. To set the stage for these developments, this study begins with a short introduction to the issues and brief examination of current historiographical trends. -

EVANGELICAL DICTIONARY of THEOLOGY

EVANGELICAL DICTIONARY of THEOLOGY THIRD EDITION Edited by DANIEL J. TREIER and WALTER A. ELWELL K Daniel J. Treier and Walter A. Elwell, eds., Evangelical Dictionary of Theology Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 1984, 2001, 2017. Used by permission. _Treier_EvangelicalDicTheo_book.indb 3 8/17/17 2:57 PM 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, 3rd edition General Editors: Daniel J. Treier and Walter A. Elwell Advisory Editors: D. Jeffrey Bingham, Cheryl Bridges Johns, John G. Stackhouse Jr., Tite Tiénou, and Kevin J. Vanhoozer © 1984, 2001, 2017 by Baker Publishing Group Published by Baker Academic a division of Baker Publishing Group P.O. Box 6287, Grand Rapids, MI 49516–6287 www.bakeracademic.com Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Treier, Daniel J., 1972– editor. | Elwell, Walter A., editor. Title: Evangelical dictionary of theology / edited by Daniel J. Treier, Walter A. Elwell. Description: Third edition. | Grand Rapids, MI : Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2017. Identifiers: LCCN 2017027228 | ISBN 9780801039461 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Theology—Dictionaries. Classification: LCC BR95 .E87 2017 | DDC 230/.0462403—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017027228 Unless otherwise labeled, Scripture quotations are from the Holy Bible, New International Version®. -

Beliefs About the Creation of the World Among Teachers in Adventist Schools in Australia and the Solomon Islands

Avondale College ResearchOnline@Avondale School of Ministry and Theology (Avondale Theology Book Chapters Seminary) 12-27-2020 Beliefs About the Creation of the World Among Teachers in Adventist Schools in Australia and the Solomon Islands Kevin C. de Berg Avondale University College, [email protected] Robert K. McIver Avondale University College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://research.avondale.edu.au/theo_chapters Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation de Berg, K. C., & McIver, R. K. (2020). Beliefs about the creation of the world among teachers in Adventist schools in Australia and the Solomon Islands. In R. McIver, S. Hattingh & P. Kilgour (Eds.). Education as preparation for eternity: Teachers in Seventh-day Adventist schools in Australia and the Solomon Islands and their perceptions of mission. Cooranbong, Australia: Avondale Academic Press. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Ministry and Theology (Avondale Seminary) at ResearchOnline@Avondale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@Avondale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 350 Chapter 24 Beliefs About the Creation of the World Among Teachers in Adventist Schools in Australia and the Solomon Islands Kevin de Berg and Robert K. McIver Avondale University College Introduction The doctrine of Creation has always been of great importance to Seventh-day Adventists (SDAs), probably because of its connection to one of their crucial distinguishing beliefs—the seventh-day Sabbath (Ex. 20:8–11). For example, as he contemplates “Seven reasons why it really does matter what we believe about Creation”, Greg King states, The seventh reason why it matters what we believe about Creation is the Sabbath. -

Table of Contents Preface

Table of Contents Preface A Tribute to Roger Nicole - Timothy George General Introduction - Frank A. James III Abbreviations Part I: Atonement in the Old and New Testaments - Charles E. Hill 1. Atonement in the Pentateuch - Emile Nicole 2. Atonement in Psalm 51 - Bruce K. Waltke 3. Atonement in Isaiah 53 - J. Alan Groves 4. Atonement in the Synoptic Gospels and Acts - Royce Gordon Gruenler 5. Atonement in John's Gospel and Epistles - J. Ramsey Michaels 6. Atonement in Romans 3:21-26 - D. A. Carson 7. Atonement in the Pauline Corpus - Richard Gaffin 8. Atonement in Hebrews - Simon J. Kistemaker 9. Atonement in James, Peter and Jude - Dan G. McCartney 10. Atonement in the Apocalypse of John - Charles E. Hill Part II: The Atonement in Church History - Frank A. James III 11. Interpreting Atonement in Augustine's Preaching - Stanley P. Rosenberg 12. The Atonement in Medieval Theology - Gwenfair M. Walters 13. The Atonement in Martin Luther's Theology - Timothy George 14. The Atonement in John Calvin's Theology - Henri Blocher 15. Definite Atonement in Historical Perspective - Raymond A. Blacketer 16. The Atonement in Herman Bavinck's Theology - Joel R. Beeke 17. The Ontological Presuppositions of Barth's Doctrine of the Atonement - Bruce L. McCor- mack 18. The Atonement in Postmodernity: Guilt, Goats and Gifts - Kevin J. Vanhoozer Part III: The Atonement in the Life of the Christian and the Church - Frank A. James III 19. The Atonement in the Life of the Christian - J. I. Packer 20. Preaching the Atonement - Sinclair B. Ferguson Postscript on Penal Substitution - Roger Nicole Select Bibliography List of Contributors Subject Index Scripture Index GloryofAtonement.book Page 7 Friday, February 13, 2004 2:59 PM PREFACE Academics are prone to lamentation—it is an occupational hazard.