Long-Term Conservation and Rehabilitation of Threatened Rain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forest Fragmentation and the Ibadan Malimbe 32

32 Forest fragmentation and the Ibadan malimbe The Ibadan malimbe is a globally distance between the two most Contact: endangered but poorly known distant occupied sites was just [email protected] forest weaver (a sparrow-like bird), 110 km. endemic to a small region of south-western Nigeria. The main factor determining the Manu SA (2001) Possible factors numbers of Ibadan malimbes in influencing the decline of Nigeria's The Ibadan malimbe was first forest patches was the local extent rarest endemic bird, the Ibadan recognised as a separate species in of forest fragmentation, with malimbe. Ostrich Supplement 1958. A handful of sightings were relatively isolated patches supporting 15: 119–121. reported during the 1960s and 1970s fewer birds. Counts of Ibadan all within 100 miles of the city of malimbes were unrelated to the area Manu SA (2002) Effects of habitat Ibadan, but a dearth of subsequent or vegetation composition of forest fragmentation on the distribution of records suggested that numbers patches. None of four commoner forest birds in south western might have declined. The widespread malimbe species were sensitive to Nigeria, with particular reference to clearance of forest for subsistence forest fragmentation. Ibadan malimbe and other malimbes. agriculture was a possible cause of D Phil thesis, University of Oxford. the apparent disappearance of Although it was encouraging to find this species. the Ibadan malimbe at 19 sites, the Manu S, Peach W and Cresswell W small range and continuing human (2005) Notes on the natural history In 1999, the RSPB funded Shiiwua pressure on remaining forest of the Ibadan malimbe, a threatened Manu to carry out a three-year study fragments make the outlook for this Nigerian endemic. -

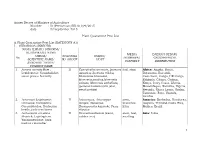

Abacca Mosaic Virus

Annex Decree of Ministry of Agriculture Number : 51/Permentan/KR.010/9/2015 date : 23 September 2015 Plant Quarantine Pest List A. Plant Quarantine Pest List (KATEGORY A1) I. SERANGGA (INSECTS) NAMA ILMIAH/ SINONIM/ KLASIFIKASI/ NAMA MEDIA DAERAH SEBAR/ UMUM/ GOLONGA INANG/ No PEMBAWA/ GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENTIFIC NAME/ N/ GROUP HOST PATHWAY DISTRIBUTION SYNONIM/ TAXON/ COMMON NAME 1. Acraea acerata Hew.; II Convolvulus arvensis, Ipomoea leaf, stem Africa: Angola, Benin, Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae; aquatica, Ipomoea triloba, Botswana, Burundi, sweet potato butterfly Merremiae bracteata, Cameroon, Congo, DR Congo, Merremia pacifica,Merremia Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, peltata, Merremia umbellata, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Ipomoea batatas (ubi jalar, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, sweet potato) Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo. Uganda, Zambia 2. Ac rocinus longimanus II Artocarpus, Artocarpus stem, America: Barbados, Honduras, Linnaeus; Coleoptera: integra, Moraceae, branches, Guyana, Trinidad,Costa Rica, Cerambycidae; Herlequin Broussonetia kazinoki, Ficus litter Mexico, Brazil beetle, jack-tree borer elastica 3. Aetherastis circulata II Hevea brasiliensis (karet, stem, leaf, Asia: India Meyrick; Lepidoptera: rubber tree) seedling Yponomeutidae; bark feeding caterpillar 1 4. Agrilus mali Matsumura; II Malus domestica (apel, apple) buds, stem, Asia: China, Korea DPR (North Coleoptera: Buprestidae; seedling, Korea), Republic of Korea apple borer, apple rhizome (South Korea) buprestid Europe: Russia 5. Agrilus planipennis II Fraxinus americana, -

Anatomical Assessment of the Fibers in the Trunk of Alstonia Boonei for Some Derived Indexes

Available online at www.worldnewsnaturalsciences.com WNOFNS 20 (2018) 54-61 EISSN 2543-5426 Anatomical assessment of the fibers in the trunk of Alstonia boonei for some derived indexes J. E. Otoide*, P. O. Tedela, O. D. Akerele and D. O. Adetunji Department of Plant Science and Biotechnology, Faculty of Science, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria *E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT Derived anatomical indexes such as Runkel’s ratio, Flexibility coefficient and Felting power / Slenderness ratio of the fibers in the trunk of Alstonia boonei were assessed using standard procedures and formulas. Significant differences (P≤ 0.05) existed in the Runkel’s ratio and Flexibility coefficient of the fibers along the axial position of the trunk, whereas, along the radial position, the differences were not significant (P≤0.05). Conversely, the Felting power/ Slenderness ratio of the fibers along the axial and radial positions of the trunk were not significantly different (P≤0.05) from one another. Totals of 0.65 ± 1.33, 68.32 ± 15.39 and 39.89 ± 15.41 were the Runkel’s ratio, Flexibility coefficient and Felting power/Slenderness ratio of the fibers. In view of the results obtained in the present assessment, assertions confirming the suitability of the trunk of Alstonia boonei as alternative sources of raw material for pulp and paper production were made. Keywords: Fibers, mean, axial and radial positions, Runkel’s ratio, Flexibility coefficient, Felting power / Slenderness ratio, Alstonia boonei 1. INTRODUCTION Burkhill (1985) described Alstonia boonei De Wild. as a tall forest tree, which can reach 45 metres (148ft) in height and 3 metres (9.8ft) in girth, the bole being cylindrical and up to 27 metres (89ft) in height with high, narrow, deep-fluted buttresses. -

Effects of Gymnemic Acid on Sweet Taste Perception in Primates

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Chemical Senses Volume 8 Number 4 1984 Effects of gymnemic acid on sweet taste perception in primates D.Glaser, G.Hellekant1, J.N.Brouwer2 and H.van der Wei2 Anthropologisches Institut der Universitdt Zurich, CH 8001 Zurich, Switzerland, ^Department of Veterinary Science, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI53706, USA, and 2Unilever Research Laboratorium Vlaardingen, The Netherlands (Received July 1983; accepted December 1983) Abstract. Application of gymnemic acid (GA) on the tongue depresses the taste of sucrose in man. This effect, as indicated by electrophysiological responses, has been found to be absent in three non- human primate species. In the present behavioral study the effect of GA on taste responses in 22 primate species, with two subspecies, and 12 human subjects has been investigated. In all the non- human primates studied, including the Pongidae which are closely related to man, GA did not sup- press the response to sucrose, only in man did GA have a depressing effect. Introduction In 1847, in a communication to the Linnean Society of London, mention was made for the first time of a particular property of a plant native to India belong- ing to the Asclepiadaceae: 'A further communication, from a letter written by Mr Edgeworth, dated Banda, 30th August, 1847, was made to the meeting, reporting a remarkable effect produced by the leaves of Gymnema sylvestris R.Br. upon the sense of taste, in reference to diminishing the perception of saccharin flavours'. Further details relating to the effect of these leaves were given by Falconer (1847/48). -

Impacts of Global Climate Change on the Phenology of African Tropical Ecosystems

IMPACTS OF GLOBAL CLIMATE CHANGE ON THE PHENOLOGY OF AFRICAN TROPICAL ECOSYSTEMS GABRIELA S. ADAMESCU MSc by Research UNIVERSITY OF YORK Biology October 2016 1 Abstract The climate has been changing at an unprecedented rate, affecting natural systems around the globe. Its impact has been mostly reflected through changes in species’ phenology, which has received extensive attention in the current global-change research, mainly in temperate regions. However, little is known about phenology in African tropical forests. Africa is known to be vulnerable to climate change and filling the gaps is an urgent matter. In this study we assess plant phenology at the individual, site and continental level. We first compare flowering and fruiting events of species shared between multiple sites, accounting for three quantitative indicators, such as frequency, fidelity for conserving a certain frequency and seasonal phase. We complement this analysis by assessing interannual trends of flowering and fruiting frequency and fidelity to their dominant frequency at 11 sites. We complete the bigger picture by analysing flowering and fruiting frequency of African tropical trees at the site and community level. Next, we correlate three climatic indices (ENSO, IOD and NAO) with flowering and fruiting events at the canopy level, at 16 sites. Our results suggest that 30 % of the studied species show plasticity or adaptability to different environments and will most likely be resilient to moderate future climate change. At both site and continental level, we found that annual flowering cycles are dominant, indicating strong seasonality in the case of more than 50% of African tropical species under investigation. -

New Birds in Africa New Birds in Africa

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 NEWNEW BIRDSBIRDS ININ AFRICAAFRICA 8 9 10 11 The last 50 years 12 13 Text by Phil Hockey 14 15 Illustrations by Martin Woodcock from Birds of Africa, vols 3 and 4, 16 reproduced with kind permission of Academic Press, and 17 David Quinn (Algerian Nuthatch) reproduced from Tits, Nuthatches & 18 Treecreepers, with kind permission of Russel Friedman Books. 19 20 New birds are still being discovered in Africa and 21 elsewhere, proof that one of the secret dreams of most birders 22 23 can still be realized. This article deals specifically with African discoveries 24 and excludes nearby Madagascar. African discoveries have ranged from the cedar forests of 25 northern Algeria, site of the discovery of the Algerian Nuthatch 26 27 (above), all the way south to the east coast of South Africa. 28 29 ome of the recent bird discoveries in Africa have come case, of their discoverer. In 1972, the late Dr Alexandre 30 Sfrom explorations of poorly-known areas, such as the Prigogine described a new species of greenbul from 31 remote highland forests of eastern Zaïre. Other new spe- Nyamupe in eastern Zaïre, which he named Andropadus 32 cies have been described by applying modern molecular hallae. The bird has never been seen or collected since and 33 techniques capable of detecting major genetic differences Prigogine himself subse- quently decided that 34 between birds that were previously thought to be races of the specimen was of a melanis- 35 the same species. The recent ‘splitting’ of the Northern tic Little Greenbul Andropadus 36 and Southern black korhaans Eupodotis afraoides/afra of virens, a species with a 37 southern Africa is one example. -

Seed Dispersal by Ceratogymna Hornbills in the Dja Reserve, Cameroon

Journal of Tropical Ecology (1998) 14:351–371. With 2 figures Copyright 1998 Cambridge University Press Seed dispersal by Ceratogymna hornbills in the Dja Reserve, Cameroon KENNETH D. WHITNEY*†1, MARK K. FOGIEL*, AARON M. LAMPERTI*, KIMBERLY M. HOLBROOK*, DONALD J. STAUFFER*, BRITTA DENISE HARDESTY*, V. THOMAS PARKER* and THOMAS B. SMITH*† *Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco, California 94132 U.S.A. †Center for Population Biology, University of California, Davis, California 95616-8755 U.S.A. (Accepted 13 January 1998) ABSTRACT. Seed dispersal is a process critical to the maintenance of tropical forests, yet little is known about the interactions of most dispersers with their communities. In the Dja Reserve, Cameroon, seed dispersal by the hornbills Cerato- gymna atrata, C. cylindricus and C. fistulator (Aves: Bucerotidae) was evaluated with respect to the taxonomic breadth of plants dispersed, location of seed deposition and effects on seed germination. Collectively, the three hornbill species consumed fruits from 59 tree and liana species, and likely provided dispersal for 56 of them. Hornbill-dispersed tree species composed 22% of the known tree flora of the site. Hornbill visit lengths, visit frequencies, and seed passage times indicated that few seeds were deposited beneath parent trees; in five hornbill/tree species pairings studied, 69–100% of the seeds ingested were deposited away from the parent trees. Germination trials showed that hornbill gut passage is gentle on seeds. Of 24 tree species tested, 23 germinated after passage by hornbills; of 17 planted with con- trols taken directly from trees, only four species showed evidence of inhibition of germination rate, while seven experienced unchanged germination rates and six experienced enhanced germination rates. -

Lecythidaceae (G.T

Flora Malesiana, Series I, Volume 21 (2013) 1–118 LECYTHIDACEAE (G.T. Prance, Kew & E.K. Kartawinata, Bogor)1 Lecythidaceae A.Rich. in Bory, Dict. Class. Hist. Nat. 9 (1825) 259 (‘Lécythidées’), nom. cons.; Poit., Mém. Mus. Hist. Nat. Paris 13 (1835) 141; Miers, Trans. Linn. Soc. London, Bot. 30, 2 (1874) 157; Nied. in Engl. & Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. 3, 7 (1892) 30; R.Knuth in Engl., Pflanzenr. IV.219, Heft 105 (1939) 26; Whitmore, Tree Fl. Malaya 2 (1973) 257; R.J.F.Hend., Fl. Australia 8 (1982) 1; Corner, Wayside Trees Malaya ed. 3, 1 (1988) 349; S.A.Mori & Prance, Fl. Neotrop. Monogr. 21, 2 (1990) 1; Chantar., Kew Bull. 50 (1995) 677; Pinard, Tree Fl. Sabah & Sarawak 4 (2002) 101; H.N.Qin & Prance, Fl. China 13 (2007) 293; Prance in Kiew et al., Fl. Penins. Malaysia, Ser. 2, 3 (2012) 175. — Myrtaceae tribus Lecythideae (A.Rich.) A.Rich. ex DC., Prodr. 3 (1828) 288. — Myrtaceae subtribus Eulecythideae Benth. & Hook.f., Gen. Pl. 1, 2 (1865) 695, nom. inval. — Type: Lecythis Loefl. Napoleaeonaceae A.Rich. in Bory, Dict. Class. Hist. Nat. 11 (1827) 432. — Lecythi- daceae subfam. Napoleonoideae Nied. in Engl. & Prantl., Nat. Pflanzenfam. 3, 7 (1893) 33. — Type: Napoleonaea P.Beauv. Scytopetalaceae Engl. in Engl. & Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam., Nachtr. 1 (1897) 242. — Lecythidaceae subfam. Scytopetaloideae (Engl.) O.Appel, Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 121 (1996) 225. — Type: Scytopetalum Pierre ex Engl. Lecythidaceae subfam. Foetidioideae Nied. in Engl. & Prantl, Nat Pflanzenfam. 3, 7 (1892) 29. — Foetidiaceae (Nied.) Airy Shaw in Willis & Airy Shaw, Dict. Fl. Pl., ed. -

Native Indigenous Tree Species Show Recalcitrance to in Vitro Culture

Journal of Agriculture and Life Sciences ISSN 2375-4214 (Print), 2375-4222 (Online) Vol. 2, No. 1; June 2015 Native Indigenous Tree Species Show Recalcitrance to in Vitro Culture Auroomooga P. Y. Yogananda Bhoyroo Vishwakalyan Faculty of Agriculture University of Mauritius Jhumka Zayd Forestry Service Ministry of Agro-Industry (Mauritius) Abstract The status of the Mauritian forest is alarming with deforestation and invasive alien species deeply affecting the indigenous flora. Therefore, major conservation strategies are needed to save the remaining endemic tree species. Explants form three endemic tree species Elaeocarpus bojeri, Foetidia mauritiana and Sideroxylon grandiflorum were grown under in vitro conditions. These species are rareand Elaeocarpus bojeri has been classified as critically endangered. Thidiazuron (TDZ) and 6-Benzylaminopurine (BAP) were used as growth promoters in order to stimulate seed germination, callus induction. Half strength Murashige and Skoog’s (MS) media supplemented with coconut water, activated charocoal and phytagel were used as growth media. Hormone levels of TDZ were 0.3mg/l and 0.6mg/l while BAP level was at 1mg/l. Germination rate for E.bojeri was low (5%) with TDZ 0.3mg/l. Sideroxylon grandiflorum seeds showed no response to in vitro culture, while F mauritiana showed successful callus induction with TDZ 0.6mg/l and 0.3mg/l. Keywords: Elaeocarpus bojeri, Foetidia mauritiana, Sideroxylon grandiflorum, in vitro culture, TDZ, BAP 1.0 Introduction The increase in population size, island development and sugarcane cultivation led to drastic deforestation that reduced the native forest to less than 2%. Mauritius has the most endangered terrestrial flora in the world according to the IUCN (Ministry of Environment & Sustainable Development (MoESD), 2011). -

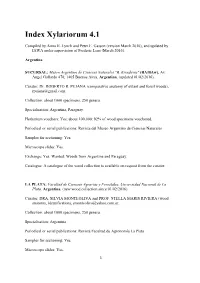

Index Xylariorum 4.1

Index Xylariorum 4.1 Compiled by Anna H. Lynch and Peter E. Gasson (version March 2010), and updated by IAWA under supervision of Frederic Lens (March 2016). Argentina SUCURSAL: Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales "B. Rivadavia" (BA/BAw), Av. Ángel Gallardo 470, 1405 Buenos Aires, Argentina. (updated 01/02/2016). Curator: Dr. ROBERTO R. PUJANA (comparative anatomy of extant and fossil woods), [email protected]. Collection: about 1000 specimens, 250 genera. Specialisation: Argentina, Paraguay. Herbarium vouchers: Yes; about 100,000; 92% of wood specimens vouchered. Periodical or serial publications: Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales Samples for sectioning: Yes. Microscope slides: Yes. Exchange: Yes. Wanted: Woods from Argentina and Paraguay. Catalogue: A catalogue of the wood collection is available on request from the curator. LA PLATA: Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias y Forestales, Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Argentina. (new wood collection since 01/02/2016). Curator: DRA. SILVIA MONTEOLIVA and PROF. STELLA MARIS RIVIERA (wood anatomy, identification), [email protected]. Collection: about 1000 specimens, 250 genera. Specialisation: Argentina Periodical or serial publications: Revista Facultad de Agronomía La Plata Samples for sectioning: Yes. Microscope slides: Yes. 1 Exchange: Yes. Wanted: woods from Argentina. Catalogue: A catalogue of the wood collection is available on request from the curator: www.maderasenargentina.com.ar TUCUMAN: Xiloteca of the Herbarium of the Fundation Miguel Lillo (LILw), Foundation Miguel Lillo - Institut Miguel Lillo, (LILw), Miguel Lillo 251, Tucuman, Argentina. (updated 05/08/2002). Foundation: 1910. Curator: MARIA EUGENIA GUANTAY, Lic. Ciencias Biologicas (anatomy of wood of Myrtaceae), [email protected]. Collection: 1,319 specimens, 224 genera. -

Ecological Report on Magombera Forest

Ecological Report on Magombera Forest Andrew R. Marshall (COMMISSIONED BY WORLD WIDE FUND FOR NATURE TANZANIA PROGRAMME OFFICE) Feb 2008 2 Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms 3 Acknowledgements 4 Executive Summary 5 Background 5 Aim and Objectives 5 Findings 6 Recommendations 7 Introduction 9 Tropical Forests 9 Magombera Location and Habitat 9 Previous Ecological Surveys 10 Management and Conservation History 11 Importance of Monitoring 14 Aim and Objectives 15 Methods 15 Threats 17 Forest Structure 17 Key Species 18 Forest Restoration 20 Results and Discussion 21 Threats 21 Forest Structure 25 Key Species 26 Forest Restoration 36 Recommendations 37 Immediate Priorities 38 Short-Term Priorities 40 Long-Term Priorities 41 References 44 Appendices 49 Appendix 1. Ministry letter of support for the increased conservation of Magombera forest 49 Appendix 2. Datasheets 50 Appendix 3. List of large trees in Magombera Forest plots 55 Appendix 4. Slides used to present ecological findings to villages 58 Appendix 5. Photographs from village workshops 64 3 Abbreviations and Acronyms CEPF Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund CITES Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species IUCN International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources TAZARA Tanzania-Zambia Railroad UFP Udzungwa Forest Project UMNP Udzungwa Mountains National Park WWF-TPO Worldwide Fund for Nature – Tanzania Programme Office 4 Acknowledgements Thanks to all of the following individuals and institutions: - CEPF for 2007 funds for fieldwork and report -

Bioefficacy of Alstonia Boonei Leaf Extract Against Cowpea Beetle Callosobrochus Maculatus Infesting Stored Cowpea Seeds in Storage

Brazilian Journal of Biological Sciences, 2018, v. 5, No. 11, p. 673-681. ISSN 2358-2731 https://doi.org/10.21472/bjbs.051106 Bioefficacy of Alstonia boonei leaf extract against cowpea beetle Callosobrochus maculatus infesting stored cowpea seeds in storage Kayode David Ileke¹ and Arotolu Temitope Emmanuel¹,² ¹Department of Biology. Federal University of Technology Akure. Nigeria. Email: [email protected]. ²Centre of Conservation Medicine and Ecological safety, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin P.R. China. Email: [email protected]. Abstract. This study was conducted to investigate the efficacy of the oils of Alstonia boonei leaf extracted with n-hexane, Received petroleum ether, methane and acetone as contact insecticides October 5, 2018 against the activities of Callosobrochus maculatus in stored cowpea seed. The oils were incorporated at rates 2.0 mL per Accepted December 23, 2018 20 g of cowpea seeds. The parameters assessed include, mortality of adult insects, oviposition and adult emergence to Released ascertain the control of the beetle. All concentration of the December 31, 2018 extracts used evoked 100% mortality of C. maculatus after 72 h of post treatment. The development of Callosobrochus maculatus Full Text Article was inversely proportional to the concentration of the oil. As the ratio of Alstonia boonei leaf oil extract increased, the mortality of the beetle increased. Therefore, complete protection of seeds and complete inhibition of adult emergence in the oils extracts of Alstonia boonei leaf were effective in controlling cowpea bruchid in stored cowpea seed. Keywords: Alstonia boonei; Leaf oil extracts; Cowpea seed; Callosobrochus maculates; Seed protection. 0000-0002-3106-4328 Kayode David Ileke 0000-0003-1330-0160 Arotolu Temitope Emmanuel Introduction most important producing areas in Nigeria are located in the savanna Cowpea Vigna unguiculata L.