Detention and Interrogation in the Post-9/11 World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Approval of George W. Bush: Economic and Media Impacts Gino Tozzi Jr

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2011 Approval of George W. Bush: Economic and media impacts Gino Tozzi Jr. Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Tozzi Jr., Gino, "Approval of George W. Bush: Economic and media impacts" (2011). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 260. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. APPROVAL OF GEORGE W. BUSH: ECONOMIC AND MEDIA IMPACTS by GINO J. TOZZI JR. DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: POLITICAL SCIENCE Approved by: _________________________________ Chair Date _________________________________ _________________________________ _________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY GINO J. TOZZI JR. 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my Father ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to thank my committee chair Professor Ewa Golebiowska for the encouragement and persistence on only accepting the best from me in this process. I also owe my committee of Professor Ronald Brown, Professor Jodi Nachtwey, and Professor David Martin a debt of gratitude for their help and advisement in this endeavor. All of them were instrumental in keeping my focus narrowed to produce the best research possible. I also owe appreciation to the commentary, suggestions, and research help from my wonderful wife Courtney Tozzi. This project was definitely more enjoyable with her encouragement and help. -

Repatriate . . . Then Compensate: Why the United States Owes Reparation Payments to Former Guantánamo Detainees

Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review Volume 48 Number 3 Developments in the Law: Election Article 8 Law; Developments in the Law: Law of War Spring 2015 Repatriate . Then Compensate: Why the United States Owes Reparation Payments to Former Guantánamo Detainees Cameron Bell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, International Humanitarian Law Commons, International Law Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, National Security Law Commons, and the President/ Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Cameron Bell, Repatriate . Then Compensate: Why the United States Owes Reparation Payments to Former Guantánamo Detainees, 48 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 867 (2015). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr/vol48/iss3/8 This Law of War Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REPATRIATE . THEN COMPENSATE: WHY THE UNITED STATES OWES REPARATION PAYMENTS TO FORMER GUANTÁNAMO DETAINEES Cameron Bell* In late 2001, U.S. government officials chose Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, as the site to house the “war on terror” detainees. Since then, 779 individuals have been detained at Guantánamo. Many of the detainees have endured years of detention, cruel and degrading treatment, and for some, torture—conduct that violates well-established prohibitions against torture and inhumane treatment under both general international law and the law of war. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States

No. ________ In the Supreme Court of the United States KHALED A. F. AL ODAH, ET AL., PETITIONERS, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ET AL., RESPONDENTS. ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI DAVID J. CYNAMON THOMAS B. WILNER MATTHEW J. MACLEAN COUNSEL OF RECORD OSMAN HANDOO NEIL H. KOSLOWE PILLSBURY WINTHROP AMANDA E. SHAFER SHAW PITTMAN LLP SHERI L. SHEPHERD 2300 N Street, N.W. SHEARMAN & STERLING LLP Washington, DC 20037 801 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W. 202-663-8000 Washington, DC 20004 202-508-8000 GITANJALI GUTIERREZ J. WELLS DIXON GEORGE BRENT MICKUM IV SHAYANA KADIDAL SPRIGGS & HOLLINGSWORTH CENTER FOR 1350 “I” Street N.W. CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS Washington, DC 20005 666 Broadway, 7th Floor 202-898-5800 New York, NY 10012 212-614-6438 Counsel for Petitioners Additional Counsel Listed on Inside Cover JOSEPH MARGULIES JOHN J. GIBBONS MACARTHUR JUSTICE CENTER LAWRENCE S. LUSTBERG NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY GIBBONS P.C. LAW SCHOOL One Gateway Center 357 East Chicago Avenue Newark, NJ 07102 Chicago, IL 60611 973-596-4500 312-503-0890 MARK S. SULLIVAN BAHER AZMY CHRISTOPHER G. KARAGHEUZOFF SETON HALL LAW SCHOOL JOSHUA COLANGELO-BRYAN CENTER FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE DORSEY & WHITNEY LLP 833 McCarter Highway 250 Park Avenue Newark, NJ 07102 New York, NY 10177 973-642-8700 212-415-9200 DAVID H. REMES MARC D. FALKOFF COVINGTON & BURLING COLLEGE OF LAW 1201 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W. NORTHERN ILLINOIS Washington, DC 20004 UNIVERSITY 202-662-5212 DeKalb, IL 60115 815-753-0660 PAMELA CHEPIGA SCOTT SULLIVAN ANDREW MATHESON DEREK JINKS KAREN LEE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SARAH HAVENS SCHOOL OF LAW ALLEN & OVERY LLP RULE OF LAW IN WARTIME 1221 Avenue of the Americas PROGRAM New York, NY 10020 727 E. -

Who Are the Guantánamo Detainees? CASE SHEET 15 Yemeni National: Abdulsalam Al-Hela 11 January 2005 AI Index: AMR 51/206/2005

USA Who are the Guantánamo detainees? CASE SHEET 15 Yemeni national: Abdulsalam al-Hela 11 January 2005 AI Index: AMR 51/206/2005 Full name: Abdulsalam al-Hela Nationality: Yemeni Occupation: Businessman Age: 34 Family status: Married with two children “Contact with him suddenly stopped…when we called him, his mobile phone rang but there was no answer”. Abdulsalam al-Hela’s brother, talking of his brother’s “disappearance” Abdulsalam al-Hela is a businessman from Sana’a, Yemen. In September 2002 he is believed to have travelled to Egypt for a meeting with Arab Contractors, an Egyptian construction firm for which he was the Yemeni representative. While there he phoned his family regularly. On the last occasion he called, his brother stated that he sounded nervous and worried, and that he had to go to a meeting. He was unwilling to say any more over the telephone. It was last time Abdulsalam al-Hela’s family would hear from him for over a year, and then it would be through a letter smuggled out of a prison in Afghanistan. Abdulsalam al-Hela appears to have been abducted by the Egyptian authorities and handed over to US officials. Abdulsalam al-Hela is convinced that the USA and Egypt conspired to lure him to Egypt with the express intention of “disappearing” him in order to interrogate him about his contacts in Yemen. As a result he became a victim of the US practice of rendition and secret detention, being taken from country to country without any recourse to a court, access to lawyers or contact with his family. -

Freedom Or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq Hannibal Travis

Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 4 Spring 2005 Freedom or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq Hannibal Travis Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr Recommended Citation Hannibal Travis, Freedom or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq, 3 Nw. J. Int'l Hum. Rts. 1 (2005). http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol3/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2005 Northwestern University School of Law Volume 3 (Spring 2005) Northwestern University Journal of International Human Rights FREEDOM OR THEOCRACY?: CONSTITUTIONALISM IN AFGHANISTAN AND IRAQ By Hannibal Travis* “Afghans are victims of the games superpowers once played: their war was once our war, and collectively we bear responsibility.”1 “In the approved version of the [Afghan] constitution, Article 3 was amended to read, ‘In Afghanistan, no law can be contrary to the beliefs and provisions of the sacred religion of Islam.’ … This very significant clause basically gives the official and nonofficial religious leaders in Afghanistan sway over every action that they might deem contrary to their beliefs, which by extension and within the Afghan cultural context, could be regarded as -

The Jose Padilla Story

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 48 Issue 1 Criminal Defense in the Age of Article 4 Terrorism January 2004 The Jose Padilla Story Donna R. Newman New York Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Donna R. Newman, The Jose Padilla Story, 48 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2003-2004). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. 18178_nlr_48-1-2 Sheet No. 23 Side A 04/27/2004 12:08:32 \\server05\productn\N\NLR\48-1-2\NLR211.txt unknown Seq: 1 16-APR-04 9:14 THE JOSE PADILLA STORY DONNA R. NEWMAN* The editors of the New York Law School Law Review have com- piled the following article primarily from briefs submitted to the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York and the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in connection with the federal government’s detention of Jose Padilla. The controver- sies connected with this case are still not resolved and new argu- ments continue to be developed as the case is briefed and presented to the Supreme Court.1 * * * “At a time like this, when emotions are understandably high, it is difficult to adopt a dispassionate attitude toward a case of this nature. -

Guantanamo and Citizenship: an Unjust Ticket Home

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 37 Issue 2 Article 19 2006 Guantanamo and Citizenship: An Unjust Ticket Home Rory T. Hood Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Rory T. Hood, Guantanamo and Citizenship: An Unjust Ticket Home, 37 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 555 (2006) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol37/iss2/19 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. GUANTANAMO AND CITIZENSHIP: AN UNJUST TICKET HOME? Rory T. Hood t "Trying to get Uganda to take an interest is pretty difficult; [JamalAbdul- lah Kiyemba has] been here since he was 14. 1 am asking the [Foreign Of- fice] whether they will allow him to apply for citizenship from Guan- tanamo Bay. If you are out of the countryfor more than two years, it can be counted against you. He probably has now been-but not of his own free will.' -Louise Christian - Atty. representing Jamal Abdullah Kiyemba I. INTRODUCTION Jamal Abdullah Kiyemba, Bisher al-Rawi, Jamil al-Banna, Shaker Abdur-Raheem Aamer, and Omar Deghayes are currently in the custody of the United States government at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.2 A citizen of Uganda, an Iraqi exile, a Jordanian refugee, a Saudi citizen, and a Libyan exile, respectively, these men form an unlikely group; yet, each share one common trait. -

Table of Contents

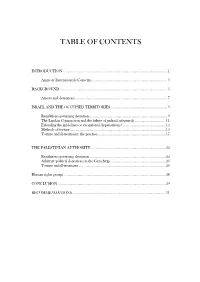

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 Amnesty International's Concerns ..................................................................................... 3 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 5 Arrests and detentions ........................................................................................................ 7 ISRAEL AND THE OCCUPIED TERRITORIES ................................................................ 9 Regulations governing detention ........................................................................................ 9 The Landau Commission and the failure of judicial safeguards ................................. 11 Extending the guidelines or exceptional dispensations? ................................................ 14 Methods of torture ............................................................................................................ 15 Torture and ill-treatment: the practice ............................................................................. 17 THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 22 Regulations governing detention ...................................................................................... 22 Arbitrary political detentions in the Gaza Strip .............................................................. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: ROBOTICS and the FUTURE OF

ABSTRACT Title of Document: ROBOTICS AND THE FUTURE OF INTERNATIONAL ASYMMETRIC WARFARE Nicholas Grossman, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Directed By: Professor George Quester, Department of Government and Politics In the post-Cold War world, the world's most powerful states have cooperated or avoided conflict with each other, easily defeated smaller state governments, engaged in protracted conflicts against insurgencies and resistance networks, and lost civilians to terrorist attacks. This dissertation explores various explanations for this pattern, proposing that some non-state networks adapt to major international transitions more quickly than bureaucratic states. Networks have taken advantage of the information technology revolution to enhance their capabilities, but states have begun to adjust, producing robotic systems with the potential to grant them an advantage in asymmetric warfare. ROBOTICS AND THE FUTURE OF ASYMMETRIC WARFARE By Nicholas Grossman Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2013 Advisory Committee: Professor George Quester, Chair Professor Paul Huth Professor Shibley Telhami Professor Piotr Swistak Professor William Nolte Professor Keith Olson © Copyright by Nicholas Grossman 2013 Dedication To Marc and Tracy Grossman, who made this all possible, and to Alyssa Prorok, who made it all worth it. ii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation committee for all the advice and support, Anne Marie Clark and Cissy Roberts for making everything run smoothly, Jacob Aronson and Rabih Helou for the comments and encouragement, Alyssa Prorok for invaluable help, and especially to George Quester for years of mentorship. -

Murat Kurnaz Released from Guantánamo!

Amnesty International 25 August 2006 AI Index AMR 51/147/2006 Murat Kurnaz had been held for four years and eight months without charge or trial. Guantánamo must be closed! Good News: Murat Kurnaz released from Guantánamo! “Thank God, I am well, but just God that created us knows when I will come back” Murat Kurnaz wrote these words to his family from Guantánamo in March 2002. His dreams of returning home to Germany have only now, finally, been realised. Released from Guantánamo on 24 August 2006, Murat Kurnaz had been held for four years and eight months without charge or trial. The only contact he had been allowed with his family was through heavily censored letters. In a statement, his German lawyer said: “He is now again in the circle of his family. Their joy at embracing their lost son again is indescribable”. Murat’s mother, Rabiye Kurnaz has dedicated these past years to campaigning for her eldest son’s release. In November 2005 she attended an international conference organized by Amnesty International and Reprieve where she spoke of her hopes of being reunited with her son. Now these hopes have become a reality. Murat Kuraz is a Turkish national who was born in Germany in 1982. His prolonged detention in Guantánamo had been complicated by his status – lacking German citizenship, the German authorities had refused his return to Germany. The Turkish authorities had shown little interest in his case. It was only after intense lobbying from his family, lawyers and AI members around the world, including in his home town of Bremen, that the German authorities began to act on his behalf, finally paving the way for his return. -

Who Is the Attorney General's Client?

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\87-3\NDL305.txt unknown Seq: 1 20-APR-12 11:03 WHO IS THE ATTORNEY GENERAL’S CLIENT? William R. Dailey, CSC* Two consecutive presidential administrations have been beset with controversies surrounding decision making in the Department of Justice, frequently arising from issues relating to the war on terrorism, but generally giving rise to accusations that the work of the Department is being unduly politicized. Much recent academic commentary has been devoted to analyzing and, typically, defending various more or less robust versions of “independence” in the Department generally and in the Attorney General in particular. This Article builds from the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Co. Accounting Oversight Board, in which the Court set forth key principles relating to the role of the President in seeing to it that the laws are faithfully executed. This Article draws upon these principles to construct a model for understanding the Attorney General’s role. Focusing on the question, “Who is the Attorney General’s client?”, the Article presumes that in the most important sense the American people are the Attorney General’s client. The Article argues, however, that that client relationship is necessarily a mediated one, with the most important mediat- ing force being the elected head of the executive branch, the President. The argument invokes historical considerations, epistemic concerns, and constitutional structure. Against a trend in recent commentary defending a robustly independent model of execu- tive branch lawyering rooted in the putative ability and obligation of executive branch lawyers to alight upon a “best view” of the law thought to have binding force even over plausible alternatives, the Article defends as legitimate and necessary a greater degree of presidential direction in the setting of legal policy. -

Combatant Status and Computer Network Attack

Combatant Status and Computer Network Attack * SEAN WATTS Introduction .......................................................................................... 392 I. State Capacity for Computer Network Attacks ......................... 397 A. Anatomy of a Computer Network Attack ....................... 399 1. CNA Intelligence Operations ............................... 399 2. CNA Acquisition and Weapon Design ................. 401 3. CNA Execution .................................................... 403 B. State Computer Network Attack Capabilites and Staffing ............................................................................ 405 C. United States’ Government Organization for Computer Network Attack .............................................. 407 II. The Geneva Tradition and Combatant Immunity ...................... 411 A. The “Current” Legal Framework..................................... 412 1. Civilian Status ...................................................... 414 2. Combatant Status .................................................. 415 3. Legal Implications of Status ................................. 420 B. Existing Legal Assessments and Scholarship.................. 424 C. Implications for Existing Computer Network Attack Organization .................................................................... 427 III. Departing from the Geneva Combatant Status Regime ............ 430 A. Interpretive Considerations ............................................. 431 * Assistant Professor, Creighton University Law School; Professor,