Clinical Excellence Series Volume VI an Evidence-Based Approach to Infectious Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOTE: the Following Are Shirley Ryan Abilitylab's Standard Charges As of Jan. 1, 2019. These Standard Charges Often Do Not

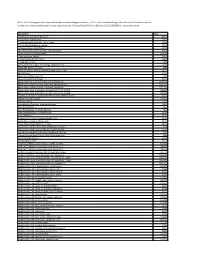

NOTE: The following are Shirley Ryan AbilityLab's standard charges as of Jan. 1, 2019. These standard charges often do not reflect what a patient or their insurance company/payer may be required to pay. Contact Patient Financial Services at 312-238-6039 for more information. Description Price 11-Deoxycortisol, Urine Random $531 12 Lead Ekg, Tracing Only $245 17 Hydroxycorticosteroids, Urine Timed $363 17 Hydroxyprogesterone, Serum $172 17 Ketosteroids, Urine Timed $273 17-Ketosteroids with Creatinine, Urine Random $273 2D Gait Analysis Charge(95999) $2,174 5' Nucleotidase, Serum $269 5.5 PDC PEDS CUFFED TRACH $226 5-HIAA-24 Hr Urine $99 A4566 Shoulder sling or vest design, abduction res $226 A4595 FES Electrode, each $38 A6545 Gradient Compression Wrap, Non-Elastic, Belo $171 ABO Rh Type $106 Above Knee Nylon Hose PR $83 Above Knee Suction Sheath $131 Above knee, for proximal femoral focal deficiency, $14,344 Above knee, molded socket, open end, SACH foot, en $10,751 Above knee, molded socket, single axis constant fr $10,935 Above knee, short prosthesis, no knee joint (""stu_L5210 $8,682 Above knee, short prosthesis, no knee joint (""stu_L5220 $7,429 ACAPELLA DH GREEN VIBRATORY PEP W/MOUTHPIECE DEVIC $181 Acetabuloplasty (27120) $4,493 Acetone, Serum $27 Acetylcholine Receptor Binding Antibody $405 Acid Phosphatase $66 Acid Phosphatase, Prostatic fraction $66 ACNE SURGERY MILIA CYSTS (10040) $530 Acorn Nebulizer $174 Activated PTT/Partial Thromboplastin Time $109 Active Wound Care > 20 cm Units $171 Active Wound Care/20 cm or < Units $171 Acupuncture with E-Stim. Each additional 15 minute $65 Acupuncture with E-Stim. -

Mantke, Peitz, Surgical Ultrasound -- Index

419 Index A esophageal 218 Anorchidism 376 gallbladder 165 Aorta 364–366 A-mode imaging 97 gastric 220 abdominal aneurysm (AAA) AAA (abdominal aortic aneurysm) metastasis 142 20–21, 364, 366 20–21, 364, 366 pancreatic 149, 225 dissection 364, 366 Abdominal wall Adenofibroma, breast 263 perforation 366 abscess 300–301 Adenoma pseudoaneurysm 364 diagnostic evaluation 297 adrenal 214 Aortic rupture 20 hematoma 73, 300, 305 colorectal 231, 232 Aplasia, muscular 272 rectus sheath 297–300 duodenal papilla 229, 231 Appendicitis 1–4 hernia 300, 302–304 gallbladder 165 consequences for surgical indications for sonography 297 hepatic 54, 58, 141 treatment 2 seroma 298, 300, 305 multiple 141 sonographic criteria 1 trauma 297–300 parathyroid 213 Archiving 418 Abortion, tubal 30 renal 241 Arteriosclerosis 346, 348 Abscess thyroid 202–203 carotid artery 335, 337, 338 abdominal wall 300–301 Adenomyomatosis 8, 164, 165 plaque 337, 338, 345, 367, 370 causes 301 Adrenal glands 214–216 Arteriovenous (AV) malformation amebic 138 adenoma 214 139, 293, 326–329 breast 264 carcinoma 214 Artery chest wall 173, 178 cyst 214 carotid 334–339 diverticular 120, 123 hematoma 214 aneurysm 338 drainage 85–88, 93 hemorrhage 214 arteriosclerosis 335 hepatic 6, 138, 398 hyperplasia 214 plaque characteristics inflammatory bowel disease limpoma/myelipoma 214 337, 338, 345 116, 119 metastases 214 bifurcation 334, 337 intramural 5 sonographic criteria 214 bulb 339 lung 183, 186, 190 tuberculosis 214 dissection 338, 339, 346 pancreatic 11 Advanced dynamic flow (ADF) sonographic -

Chewable Lozenge Formulation

Umashankar M S et al. Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2016, 7 (4) INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH JOURNAL OF PHARMACY www.irjponline.com ISSN 2230 – 8407 Review Article CHEWABLE LOZENGE FORMULATION- A REVIEW Umashankar M S *, Dinesh S R, Rini R, Lakshmi K S, Damodharan N SRM College of Pharmacy, SRM University, Kattankulathur, India *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] Article Received on: 11/02/16 Revised on: 13/03/16 Approved for publication: 28/03/16 DOI: 10.7897/2230-8407.07432 ABSTRACT Development of lozenges dated back to 20thcentury and is still remain popular among the consumer and hence it has continued commercial production. Lozenges are palatable solid unit dosage form administrated in the oral cavity. They meant to be dissolved in mouth or pharynx for its local or systemic effect. Lozenge tablets provide several advantages as pharmaceutical formulations however with some disadvantages. Lozenge as a dosage form can be adopted for drug delivery across buccal route, labial route, gingival route and sublingual route. Multiple drugs can also be incorporated in them for chronic illness treatments. Lozenge enables loading of wide range of active ingredients for oral systemic delivery of drugs. Lozenges are available as over the counter medications in the form of caramel based soft lozenges, hard candy lozenges and compressed tablet lozenges containing drugs for sore throat, mouth infection and as mouth fresheners. The rationale behind the use of medicated lozenges as one of the most favored dosage form for the delivery of antitussive drugs. This review focuses various aspects of lozenge formulation providing an insight to the formulation scientist on novel application of lozenge drug delivery system. -

Sore Throats

Pharyngitis Viruses cause most sore throats. When viruses infect your nose, $\/�P�1S1N(f F'ac+s: throat and sinuses, your body fightsback by making mucus. This helps Only about 15% of the people who wash out viruses. The mucus from your nose and sinuses drains into go to a doctor with a bad sore your throat. It can make your throat feel sore. Allergies, smoking, and throat have strep throat. You need air pollution can also lead to a sore throat. Some sore throats happen a test to tell for sure. You only need when stomach acid comes up into the throat. Yelling or speaking for a antibiotics if your test shows you long time can also make the throat sore. have strep throat. WJ.1affo l)O: Antibiotics don't work against viral infections. A sore throat • Drink more water. Honey and from a virus will get better on its own within a week or two. Antibiotics lemon in hot water or herbal teas won't make a sore throat go away any faster if it is caused by a virus. are good, too. Do not give honey Taking antibiotics when they are not needed may harm you by creating to children under 1. stronger germs. • Gargle with warm salt water. Talk with your health care provider about medicines that can help you • Suck on a hard candy, vitamin C feel better. For sore throats caused by allergies, your provider can help drop or throat lozenge. Do not give to young children. you figureout how to avoid the things that trigger your allergies. -

Submission Demonstrates That Flurbiprofen Lozenges Do Not Need to Be Restricted to Pharmacy Only Status Given;

Flurbiprofen reclassification to Unscheduled Medicine Reckitt Benckiser __________________________________________________________________________________________ Reclassification of a Medicine for consideration by the Medicine Classification Committee Application for the reclassification of flurbiprofen lozenges (8.75 mg flurbiprofen per lozenge) from Pharmacy Only Medicine to General Sale (Unscheduled) Medicine 30 June 2020 Submitted by: Reckitt Benckiser (New Zealand) Pty Limited Level 47 / 680 George Street Sydney NSW 2000, Australia 1 | Page Flurbiprofen reclassification to Unscheduled Medicine Reckitt Benckiser __________________________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 4 Part A ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 1. International Non-proprietary Name of the medicine. ........................................................ 7 2. Proprietary name(s). ................................................................................................................ 7 3. Name and contact details of the company / organisation / individual requesting a reclassification. ............................................................................................................................. 7 4. Dose form(s) and strength(s) for which a change is -

The Effect of Flurbiprofen on Postoperative Sore Throat And

Turk J Anaesth Reanim 2014; 42: 123-7 DOI: 10.5152/TJAR.2014.35693 The Effect of Flurbiprofen on Postoperative Sore Throat and Hoarseness After LMA-ProSeal Insertion: A Randomised, Clinical Trial Flurbiprofenin LMA- Proseal Uygulaması Sonrası Postoperatif Boğaz Ağrısı ve Ses Kısıklığı Üzerine Original Article AraştırmaOriginal / Özgün Etkisi: Randomize Klinik Çalışma Neslihan Uztüre, Ferdi Menda, Sevgi Bilgen, Özgül Keskin, Sibel Temur, Özge Köner Department of Anaesthesiology and Reanimation, Yeditepe University Faculty of Medicine, İstanbul, Turkey Objective: We hypothesized that flurbiprofen lozenges reduce the Amaç: Proseal laringeal maske ile ilişkili postoperatif boğaz ağrısı, ProSeal laryngeal mask airway (LMA) related symptoms of Post ses kısıklığı ve disfaji semptomlarını flurbiprofen pastilin azalttığı Operative Sore Throat (POST), hoarseness and dysphagia com- varsayımını gösterebilmek. pared to placebo lozenges. Yöntemler: Laringeal Maske (LMA) ile genel anestezi uygula- Abstract / Özet Abstract Methods: Eighty American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) I–II nacak 80 American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) I-II hasta patients undergoing general anaesthesia with LMA were included çalışmaya alındı. Prospektif, randomize, plasebo kontrollü, klinik in this prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical and sin- ve tek merkezli (üniversite hastanesi) bir çalışma idi. Anestezi in- gle centre (university hospital) study. Group F received an 8.75 mg düksiyonundan 45 dakika önce Grup F’ye 8,75 mg flurbiprofen flurbiprofen -

How to Take Care of Your Sick Family

How to Take Care of Your Sick Family Molina Healthcare 24 Hour Nurse Advice Line 1-888-275-8750 TTY: 1-800-688-4889 Molina Healthcare Línea de TeleSalud Disponible las 24 Horas 1-866-648-3537 TTY: 1-866-833-4703 Important Phone Numbers 24 Hour Línea de TeleSalud Nurse Advice Line Disponible las 24 Horas 1-888-275-8750 1-866-648-3537 TTY: 1-800-688-4889 TTY: 1-866-833-4703 Family: Neighbor: Other: 1 Table of Contents How to Take Care of Your Sick Family Introduction...................................................2 Crying or Fussy Baby....................................4 Stomach Pain.................................................5 Headache........................................................8 Sore Throat...................................................11 Cough and Cold..........................................15 Painful Urination (Peeing).........................20 Ear Pain.........................................................23 Vomiting (Throwing Up)...........................26 Fever...............................................................30 Diarrhea........................................................34 Asthma or Trouble Breathing....................40 Constipation.................................................44 If you need this information in another language, large print, Braille, or in audio format please contact the number for Member Services on the back of your card. 2 3 Introduction help you decide if you or your family When your family does not feel well, you needs to see a health care want to help them provider. They can also let right away. This you know where your booklet gives you Provider’s office is. some quick tips on You can call our nurses 24 what you can do. hours a day, on any day. You should not use this booklet in place Nurse Advice Line La Línea de TeleSalud of what your health 1-888-275-8750 1-866-648-3537 care provider tells TTY: 1-800-688-4889 TTY: 1-866-833-4703 you. -

Preferred Drug List Mercy Care

Preferred Drug List Mercy Care Table of Contents *ADHD/ANTI-NARCOLEPSY/ANTI-OBESITY/ANOREXIANTS*....................................................................5 *ALTERNATIVE MEDICINES*............................................................................................................................. 8 *AMINOGLYCOSIDES*......................................................................................................................................... 8 *ANALGESICS - ANTI-INFLAMMATORY*........................................................................................................ 8 *ANALGESICS - NONNARCOTIC*.....................................................................................................................11 *ANALGESICS - OPIOID*.................................................................................................................................... 12 *ANDROGENS-ANABOLIC*............................................................................................................................... 15 *ANORECTAL AGENTS*.....................................................................................................................................15 *ANTACIDS*..........................................................................................................................................................16 *ANTHELMINTICS*............................................................................................................................................. 16 *ANTIANGINAL -

Medicaid-Approved Preferred Drug List

New York Medicaid Medicaid-Approved Preferred Drug List Effective August 26, 2021 Legend In each class, drugs are listed alphabetically by either brand name or generic name. Brand name drug: Uppercase in bold type Generic drug: Lowercase in plain type AL: Age Limit Restrictions DO: Dose Optimization Program GR: Gender Restriction OTC: Over the counter medication available with a prescription. (Prescribers please indicate OTC on the prescription) PA: Prior authorization is required. Prior authorization is the process of obtaining approval of benefits before certain prescriptions are filled. QL: Quantity limits; certain prescription medications have specific quantity limits per prescription or per month. SP: Specialty Pharmacy ST: Step therapy is required. You may need to use one medication before benefits for the use of another medication can be authorized. MAT: Medication Assisted Therapy https://newyork.fhsc.com/providers/mat.asp Drug Name Reference Notes *ADHD/ANTI-NARCOLEPSY/ANTI- OBESITY/ANOREXIANTS* amphetamine-dextroamphet er oral capsule extended release 24 hour 10 mg, 15 mg, 5 Adderall XR DO; AL; QL mg amphetamine-dextroamphet er oral capsule extended release 24 hour 20 mg, 25 mg, 30 Adderall XR AL; QL mg amphetamine-dextroamphetamine oral Adderall DO; AL; QL tablet 10 mg, 12.5 mg, 15 mg, 5 mg, 7.5 mg amphetamine-dextroamphetamine oral Adderall AL tablet 20 mg, 30 mg atomoxetine hcl oral capsule Strattera DO; AL; QL caffeine citrate intravenous solution Cafcit caffeine citrate oral solution clonidine hcl er oral tablet extended -

Admissions Packet

Checklist for Admission Consent Forms *please read carefully and make sure all required forms are signed and completed* Name of Form Done Action Required Required Documents ☐ Must include with consent forms Admissions Record (pg. 1) Fill out completely ☐ *Please provide social security number* Privacy Practices Information (pg. 2-4) Keep Read HIPAA Acknowledgement (pg. 5) ☐ Fill out and sign Custodial Verification (pg. 6) ☐ Fill out, sign and attach applicable documentation Consent & Conditions (pg. 7-8) ☐ Fill out and sign Consent for Psychotherapy (pg. 9) ☐ Sign Seclusion & Restraint (pg. 10) ☐ Sign Individual Education Program (pg. 11) ☐ Fill out, sign and attach IEP if applicable Placement Disruption Agreement (pg. 12) ☐ Fill out and sign Permission for Adventure Outings (pg. 13) ☐ Check boxes, Initial and Sign Pivot Adventure (pg. 14) ☐ Sign Resident Rights Information (pg. 15) ☐ Fill out and sign Parent Financial Agreement (pg. 16) ☐ Fill out and sign Caseworker Financial Agreement (pg. 17) ☐ Fill out and sign Medication Reconciliation/Orders (pg. 18) ☐ Fill out completely and sign Immunizations (pg. 19) ☐ Sign & fill out or attach documentation Over the Counter Med Consent (pg. 20) ☐ Fill out and sign Resident Contact List (pg. 21) ☐ All individuals allowed to contact resident Student Record Request (pg. 22) ☐ Fill out as completely as possible Release of Information (pg. 23) Sign & fill out or make copies for all ☐ facilities/providers you desire to authorize Insurance Documentation (pg. 24) Fill out applicable sections - Please list Vision and ☐ *List Vision and Dental* Dental Insurances Resident Inventory (pg. 25) List all unperishable items (clothing, bedding, ☐ stuffed animals, etc.) the resident will be bringing Telehealth Informed Consent Form (pg. -

Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of A

J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci (www.cspsCanada.org) 15(2) 281 - 294, 2012 Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of a Single Dose of an Amylmetacresol/2,4-dichlorobenzyl Alcohol Plus Lidocaine Lozenge or a Hexylresorcinol Lozenge for the Treatment of Acute Sore Throat Due to Upper Respiratory Tract Infection Damien McNally,1 Adrian Shephard,2 Emma Field3 1 Ormeau Health Centre, Belfast, UK; 2 Professional Relations, Reckitt Benckiser, Slough, UK; 3 Global Medical Affairs, Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare, Hull, UK. Received, January 31, 2012; Revised, February 24, 2012; Accepted, April 1, 2012; Published, April 2, 2012. ABSTRACT - Purpose: Sore throat is a frequent reason for seeking medical care but few prescription options are available. Lozenges are effective in delivering active ingredients to the throat. This study was conducted to determine the analgesic efficacy of two lozenges one containing amylmetacresol (AMC)/2,4- dichlorobenzyl alcohol (DCBA) and lidocaine and one containing hexylresorcinol versus placebo in patients with acute sore throat due to upper respiratory tract infection (URTI). Methods: This was a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, parallel group, placebo-controlled study. In total, 190 patients were randomised 1:1:1 to a single dose of AMC/DCBA + lidocaine, hexylresorcinol or placebo lozenge. Subjective ratings of throat soreness, difficulty swallowing, swollen throat, numbing, and sore throat relief were obtained up to 2 hours post dose. Patient and investigator global ratings and a consumer questionnaire -

Common Pediatric Pulmonary Issues

Common Pediatric Pulmonary Issues Chris Woleben MD, FAAP Associate Dean, Student Affairs VCU School of Medicine Assistant Professor, Emergency Medicine and Pediatrics Objectives • Learn common causes of upper and lower airway disease in the pediatric population • Learn basic management skills for common pediatric pulmonary problems Upper Airway Disease • Extrathoracic structures • Pharynx, larynx, trachea • Stridor • Externally audible sound produced by turbulent flow through narrowed airway • Signifies partial airway obstruction • May be acute or chronic Remember Physics? Poiseuille’s Law Acute Stridor • Febrile • Laryngotracheitis (croup) • Retropharyngeal abscess • Epiglottitis • Bacterial tracheitis • Afebrile • Foreign body • Caustic or thermal airway injury • Angioedema Croup - Epidemiology • Usually 6 to 36 months old • Males > Females (3:2) • Fall / Winter predilection • Common causes: • Parainfluenza • RSV • Adenovirus • Influenza Croup - Pathophysiology • Begins with URI symptoms and fever • Infection spreads from nasopharynx to larynx and trachea • Subglottic mucosal swelling and secretions lead to narrowed airway • Development of barky, “seal-like” cough with inspiratory stridor • Symptoms worse at night Croup - Management • Keep child as calm as possible, usually sitting in parent’s lap • Humidified saline via nebulizer • Steroids (Dexamethasone 0.6 mg/kg) • Oral and IM route both acceptable • Racemic Epinephrine • <10kg: 0.25 mg via nebulizer • >10kg: 0.5 mg via nebulizer Croup – Management • Must observe for 4 hours after