Aylesbury Historic Town Assessment Draft Report 40 Archive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

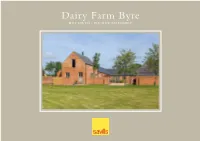

Dairy Farm Byre HILLESDEN • BUCKINGHAMSHIRE View from the Front of the House

Dairy Farm Byre HILLESDEN • BUCKINGHAMSHIRE View from the front of the house Dairy Farm Byre HILLESDEN • BUCKINGHAMSHIRE Approximate distances: Buckingham 3 miles • M40 (J9) 9 miles • Bicester 9 miles Brackley 10 miles • Milton Keynes 14 miles • Oxford 18 miles. Recently renovated barn, providing flexible accommodation in an enviable rural location Entrance hall • cloakroom • kitchen/breakfast room Utility/boot room • drawing/dining room • study Master bedroom with dressing room and en suite bathroom Bedroom two and shower room • two further bedrooms • family bathroom Ample off road parking • garden • car port SAVILLS BANBURY 36 South Bar, Banbury, Oxfordshire, OX16 9AE 01295 228 000 [email protected] Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text DESCRIPTION Entrance hall with double faced wood burning stove,(to kitchen and entrance hall) oak staircase to first floor, under stairs cupboard and limestone flooring with underfloor heating leads through to the large kitchen/breakfast room. Beautifully presented kitchen with bespoke units finished with Caesar stone work surfaces. There is a Britannia fan oven, 5 ring electric induction hob, built in fridge/freezer. Walk in cold pantry with built in shelves. East facing oak glass doors lead out onto the front patio capturing the morning sun creating a light bright entertaining space. Utility/boot room has easy access via a stable door, to the rear garden and bbq area, this also has limestone flooring. Space for washing machine and tumble dryer. Steps up to the drawing/dining room with oak flooring, vaulted ceiling and exposed wooden beam trusses. This room has glass oak framed doors leading to the front and rear west facing garden. -

16.0 Management/Restoration of Particular Features

AYLESBURY VALE DISTRICT COUNCIL Conservation Area Management Plan – District Wide Strategy 16.0 Management/restoration of particular features 16.1 Aims 16.2 Issues for Aylesbury Vale in relation to the management/restoration of particular I Clearly identify those features (such as traditional features street signage for example) which make a positive contribution to the character and appearance of the 16.2.1 There are three groups of features that stand out conservation area in the appraisal from analysis of the sample survey and through I Produce information leaflets on the importance of consultation with local groups and development certain features including why they are important control. These are: and general advice on their care and management – these should be distributed to every household within I Shopfronts the conservation area(s) subject to available I Boundary walls resources I Traditional paving materials I Build a case (based on the thorough analysis of the conservation area) for a grant fund to be established 16.2.2 Shopfronts are strongly represented in identifying the particular feature for repair and Aylesbury and Buckingham (and Winslow and reinstatement Wendover outside the sample survey) and despite a I Seek regional or local sponsorship of a scheme for good shopfront design guide, the issues of poor quality, the reinstatement of particular features such as badly designed shopfronts, inappropriate materials for shopfronts fascias and poor colour schemes and lighting design I Consultation with grant providers such as English are still significant issues in these market towns. Heritage and the Heritage Lottery Fund should establish at an early stage the potential success of an 16.2.3 Boundary walls are a district-wide issue and are application and identify a stream of funding for also a Buildings at Risk issue throughout the district. -

Ridge View, 1 Fleet Marston Cottages, Fleet Marston, Buckinghamshire, HP18 0PZ

Ridge View, 1 Fleet Marston Cottages, Fleet Marston, Buckinghamshire, HP18 0PZ Aylesbury 1.5 miles (Marylebone 55 mins.), Thame 10 miles, Milton Keynes 18 miles (Distances approx.) RIDGE VIEW, 1 FLEET MARSTON COTTAGES, FLEET MARSTON, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE HP18 0PZ A REFURBISHED COTTAGE EXTENDED OVER TIME TO NOW PROVIDE SIZEABLE ACCOMMODATION IN A QUARTER OF AN ACRE PLOT. RURAL LOCATION WITH FAR REACHING VIEWS JUST TWO MILES FROM AYLESBURY AND FIVE MINUTES FROM AYLESBURY VALE PARKWAY STATION. WADDESDON SCHOOL CATCHMENT Entrance Hall, Large Open Plan Sitting Room, Wonderful Garden Room, Kitchen/Dining Room, Cloakroom, Utility Room, Master Bedroom with Dressing Area and Bathroom, Three Further Double Bedrooms, Family Bathroom, Driveway Parking, Garage, Large Garden Backing onto Countryside Guide Price £485,000 Freehold LOCATION DESCRIPTION Marston comes from the words ‘Mersc and Tun’ meaning Marsh Ridge View is situated in a rural location with open countryside to the Farm. The epithet Fleet refers to a ‘Fleet’ of Brackish water. rear and superb views. The property dates from the late 1900’s and Fleet Marston is a small hamlet of houses either side of the A41 near has been greatly extended over the years, the most recent addition an Aylesbury with an early fourteenth century church. Although excellent garden room which really opens up the ground floor. The slightly larger now ‘Magna Britannia’ from 1806 states only 22 accommodation is very well presented, the current owners having inhabitants living in four houses. Waddesdon (2 ½ miles) has a shop undertaken refurbishment throughout. In the entrance hall are for day to day needs or alternatively Aylesbury is also 2 miles, with floorboards and the staircase, off to the side a cloakroom. -

Historic Walk-Thame-U3A-Draft 4

Historic Walk – Thame & District U3A This rural walk along the River Thame passes through a number of villages of historical interest and visits the 15th century architectural gems of Rycote Chapel and Waterstock Mill. Starting at the church at Shabbington in Buckinghamshire the route soon crosses the River Thame into Oxfordshire and follows the river, before crossing the old railway line to reach Rycote Chapel. From Rycote the route follows an undulating track to Albury and then on to Tiddington. Heading south in Tiddington the route circles west to cross the railway line again before arriving at Waterstock via the golf course. Here there is an opportunity to visit the old mill before returning via the 17th century bridge at Ickford and back into Buckinghamshire. The small hamlet of Little Ickford is the last port of call before returning across the fields to Shabbington. In winter the conditions underfoot can be muddy and in times of flood parts of the route are impassable. Walk Length The main walk (Walk A) is just over 8.5 miles (13.8 km) long (inclusive of two detours to Rycote Chapel and Waterstock Mill) and is reasonably flat. At a medium walking pace this should take 3.5 to 4 hours but time needs to be added on to appreciate the points of interest along the way. Walk B is 5.8 miles (9.4 km) a shorter version of Walk A, missing out some of Tiddington and Waterstock. Walk C is another shorter variation of 4.7 miles (7.5 km), taking in Ickford Bridge, Albury and Waterstock but missing out Rycote Chapel and Shabbington. -

14Th Regiment in NZ

14th REGIMENT OF FOOT (BUCKINGHAMSHIRE) 2nd BATTALION IN NEW ZEALAND 1860 - 1870 Private 1864 GERALD J. ELLOTT MNZM RDP FRPSL FRPSNZ AUGUST 2017 14th Regiment Buckinghamshire 2nd Battalion Sir Edward Hales formed the 14th Regiment in 1685, from a company of one hundred musketeers and pikemen recruited at Canterbury and in the neighbourhood. On the 1st January 1686, the establishment consisted of ten Companies, three Officers, two Sergeants, two corporals, one Drummer and 50 soldiers plus staff. In 1751 the Regiment officially became known as the 14th Foot instead of by the Colonel’s name. The Regiment was engaged in action both at home and abroad. In 1804 a second battalion was formed at Bedford, by Lieut-Colonel William Bligh, and was disbanded in 1817 after service in the Ionian Islands. In 1813 a third battalion was formed by Lieut-Colonel James Stewart from volunteers from the Militia, but this battalion was disbanded in 1816. The Regiment was sent to the Crimea in 1855, and Brevet Lieut-Colonel Sir James Alexander joined them after resigning his Staff appointment in Canada. In January 1858, the Regiment was reformed into two Battalions, and Lieut- Colonel Bell, VC., was appointed Lieut-Colonel of the Regiment. On 1 April 1858, the establishment of the 2nd Battalion was increased to 12 Companies, and the rank and file from 708 to 956. On the 23 April 1858, Lieut-Colonel Sir James Alexander assumed command of the 2nd. Battalion. Lieut-Colonel Bell returned to the 23rd Royal Welsh Fusiliers. The 2nd. Battalion at this time numbered only 395 NCO’s and men, but by April 1859 it was up to full establishment, recruits being obtained mainly from the Liverpool district. -

Buckinghamshire Historic Town Project

Long Crendon Historic Town Assessment Consultation Report 1 Appendix: Chronology & Glossary of Terms 1.1 Chronology (taken from Unlocking Buckinghamshire’s Past Website) For the purposes of this study the period divisions correspond to those used by the Buckinghamshire and Milton Keynes Historic Environment Records. Broad Period Chronology Specific periods 10,000 BC – Palaeolithic Pre 10,000 BC AD 43 Mesolithic 10,000 – 4000 BC Prehistoric Neolithic 4000 – 2350 BC Bronze Age 2350 – 700 BC Iron Age 700 BC – AD 43 AD 43 – AD Roman Expedition by Julius Caesar 55 BC Roman 410 Saxon AD 410 – 1066 First recorded Viking raids AD 789 1066 – 1536 Battle of Hastings – Norman Conquest 1066 Wars of the Roses – Start of Tudor period 1485 Medieval Built Environment: Medieval Pre 1536 1536 – 1800 Dissolution of the Monasteries 1536 and 1539 Civil War 1642-1651 Post Medieval Built Environment: Post Medieval 1536-1850 Built Environment: Later Post Medieval 1700-1850 1800 - Present Victorian Period 1837-1901 World War I 1914-1918 World War II 1939-1945 Cold War 1946-1989 Modern Built Environment: Early Modern 1850-1945 Built Environment: Post War period 1945-1980 Built Environment: Late modern-21st Century Post 1980 1.2 Abbreviations Used BGS British Geological Survey EH English Heritage GIS Geographic Information Systems HER Historic Environment Record OD Ordnance Datum OS Ordnance Survey 1.3 Glossary of Terms Terms Definition Building Assessment of the structure of a building recording Capital Main house of an estate, normally the house in which the owner of the estate lived or Messuage regularly visited Deer Park area of land approximately 120 acres or larger in size that was enclosed either by a wall or more often by an embankment or park pale and were exclusively used for hunting deer. -

Quarrendon Fields Aylesbury Buckinghamshire

QUARRENDON FIELDS AYLESBURY BUCKINGHAMSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL FIELD EVALUATION Document: 2009/103 Project: BA1519 15th January 2010 Compiled by Checked by Approved by James Newboult Joe Abrams Drew Shotliff Produced for: Hives Planning On behalf of: Arnold White Estates Ltd © Copyright Albion Archaeology 2010, all rights reserved Albion Archaeology Contents Key Terms...........................................................................................................................................4 Preface.................................................................................................................................................5 Structure of this Report.....................................................................................................................5 Non-Technical Summary...................................................................................................................6 1. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................... 7 1.1 Project background .............................................................................................................7 1.2 Location and Archaeological Background.........................................................................8 2. METHODOLOGY..................................................................................... 9 2.1 Introduction..........................................................................................................................9 2.2 Cropmark Analysis..............................................................................................................9 -

The Early History of Buckingham County

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 4-1-1955 The ae rly history of Buckingham County James Meade Anderson Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Recommended Citation Anderson, James Meade, "The ae rly history of Buckingham County" (1955). Master's Theses. Paper 98. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SUBMITTED TO T.dE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE IDITVERSITY. OF RICHMOND IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT IN THE CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF. ARTS THE EARLY HISTORY OF BUCKINGHAM COUliTY by James ~feade Anderson, Jr. May i, 1957 Graduate School of the University of Richmond LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND, VIRGINIA DEDICATION For five generations• since before the county was formed, Buckingham County, Virginia has been home to my family~ Their customs, habits and way or life has proerassed along with the growth of the county. It is to Buckingham County that ve owe our heritage as well as our way of life for it has been our place to ~rorship God as well as our home. It is with this thought in mind, that to my family, this paper is respectfully and fondly dedicated. James Meade Anderson, junior Andersonville, Virginia May 19.75' University of Richmond, Virginia TABLE OF COI-TTEWTS THE SETTLEMENT -

Age 25 Army Unit 3Rd Brigade Canadian Field Artillery Enlisted: January 1915 in Canadian Expeditionary Force

Arthur Kempster Corporal - Service No. 42703 - Age 25 Army Unit 3rd Brigade Canadian Field Artillery Enlisted: January 1915 in Canadian Expeditionary Force Arthur was born on the 8th May 1893 in Wingrave. The son of George and Sarah (nee Jakeman) Kempster, he was brought up in Crafton with 6 other children, his father was a shepherd. In 1911 he and his brother were butcher’s assistants in Wealdstone, Middlesex. He died on the 19th November 1918 from mustard gas and influenza. He is buried in Wingrave Congregational Chapel Yard and is also commemorated at All Saints, Wing. His brother, Harry Fredrick Kempster was born in Wingrave in 1890. He died on the 2nd October 1917 in Flanders, Belgium. Harry was a rifleman with the Royal Irish Rifles, 7th Battalion. Whilst killed in action, he is not mentioned on the Mentmore War Memorial. © Mentmore Parish History Group. With thanks to Andy Cooke, John Smith (Cheddington History Soc), Lynda Sharp and Karen Thomas for research and information. Ernest Taylor Private - Service No. 29168 - Age 30 6th Battalion Duke of Wellington’s [West Riding] Regiment. Enlisted: Huddersfield Died July 27th 1918, in the No 3 Australian Causality Clearing station, Brandhoek. Suffered gunshot wounds to his back, forehead and neck. Buried Esquelbecq Military Cemetery III D 14. Born 1887 Cheddington, Son of William and Mary (nee Baker) Taylor Ernest married Elizabeth Kelly (nee Firth). Elizabeth was a widow with four small children. The couple met and married in Huddersfield and had a child of their own on 11th Nov 1916. Ernest had worked on a local farm in Cheddington then he moved to Huddersfield where he became a goods porter. -

Aylesbury Vale Community Chest Grants April 2014 - March 2015

Aylesbury Vale Community Chest Grants April 2014 - March 2015 Amount Granted Total Cost Award Aylesbury Vale Ward Name of Organisation £ £ Date Purpose Area Buckinghamshire County Local Areas Artfully Reliable Theatre Society 1,000 1,039 Sep-14 Keyboard for rehearsals and performances Aston Clinton Wendover Aylesbury & District Table Tennis League 900 2,012 Sep-14 Wall coverings and additional tables Quarrendon Greater Aylesbury Aylesbury Astronomical Society 900 3,264 Aug-14 new telescope mount to enable more community open events and astrophotography Waddesdon Waddesdon/Haddenham Aylesbury Youth Action 900 2,153 Jul-14 Vtrek - youth volunteering from Buckingham to Aylesbury, August 2014 Vale West Buckingham/Waddesdon Bearbrook Running Club 900 1,015 Mar-15 Training and raceday equipment Mandeville & Elm Farm Greater Aylesbury Bierton with Broughton Parish Council 850 1,411 Aug-14 New goalposts and goal mouth repairs Bierton Greater Aylesbury Brill Memorial Hall 1,000 6,000 Aug-14 New internal and external doors to improve insulation, fire safety and security Brill Haddenham and Long Crendon Buckingham and District Mencap 900 2,700 Feb-15 Social evenings and trip to Buckingham Town Pantomime Luffield Abbey Buckingham Buckingham Town Cricket Club 900 1,000 Feb-15 Cricket equipment for junior section Buckingham South Buckingham Buckland and Aston Clinton Cricket Club 700 764 Jun-14 Replacement netting for existing practice net frames Aston Clinton Wendover Bucks Play Association 955 6,500 Apr-14 Under 5s area at Play in The Park event -

Peasants, Peers and Graziers: the Landscape of Quarrendon In

PEASANTS, PEERS AND GRAZIERS: THE LANDSCAPE OF QUARRENDON, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE, INTERPRETED PAUL EVERSON The medieval and later earthworks at Quarrendon, surveyed by staff of the former Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England (now English Heritage), are described and interpreted. They reveal a sequence of major land-use phases that can be related coherently to topographical, documentary and architectural evidence. The earliest element may be the site of St Peter's church, located alongside a causeway. The evidence for its architectural development and decline is assem- bled. The site of a set of almshouses in the churchyard is identified. In the later medieval period, there were two separate foci of settlement, each similarly comprising a loose grouping of farmsteads around a green. It is argued that these form components of a form of dispersed settlement pattern in the parish and wider locality. Following conversion for sheep, depopulation and engrossment by the Lee family, merchant graziers of Warwick, a 16th-century moated country mansion was created, with accompanying formal gardens, warren and park. This was one of a group of residences in Buckinghamshire and north Oxfordshire of Sir Henry Lee, creator of the Accession Day tournaments for Elizabeth I and queen's champion. A tenanted farm, its farmhouse probably reusing a retained fragment of the earlier great house, replaced this house. The sites of agricultural cottages and oxpens of an early modern regime of grazing and cattle fattening are identified. In discussion, access and water supply to the great house, and the symbolism of the formal gardens, almshouses and warren are explored. -

District of Aylesbury Vale

Appendix A DISTRICT OF AYLESBURY VALE REPRESENTATION OF THE PEOPLE ACT, 1983 LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT, 1972 AYLESBURY PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY SCHEDULE OF POLLING DISTRICTS AND POLLING PLACES The Aylesbury Vale District Council has designated the following Polling Districts and Polling Places for the Aylesbury Parliamentary Constituency. These Polling Districts and Polling Places will come into effect following the making of The Aylesbury Vale (Electoral Changes) Order 2014. The Polling District is also the Polling Place except where indicated. The same Polling Districts and Polling Places will also apply for local elections. Whilst indicative Polling Stations are shown it is for the Returning Officer for the particular election to determine the location of the Polling Station. Where a boundary is described or shown on a map as running along a road, railway line, footway, watercourse or similar geographical feature, it shall be treated as running along the centre line of the feature. Polling District/Description of Polling Polling Place Indicative Polling District Station Aylesbury Baptist Church, Bedgrove No. 1 Limes Avenue That part of the Bedgrove Ward of Aylesbury Town to the north of a line commencing at Tring Road running south-westwards from 2 Bedgrove to the rear of properties in Bedgrove and Camborne Avenue (but reverting to the road where there is no frontage residential property) to Turnfurlong Lane, thence north-westwards along Turnfurlong Lane to the north-western boundary of No. 1A, thence north-eastwards along the rear boundary of 1 – 14 Windsor Road and 2 – 4 Hazell Avenue to St Josephs RC First School, thence following the south- eastern and north-eastern perimeter of the school site to join and follow the rear boundary of properties in King Edward Avenue, thence around the south-eastern side of 118 Tring Road to the Ward boundary at Tring Road.