1 [Saxonbucks4: 15.11.2006 Version] Apart from the Introductory Section

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ridge View, 1 Fleet Marston Cottages, Fleet Marston, Buckinghamshire, HP18 0PZ

Ridge View, 1 Fleet Marston Cottages, Fleet Marston, Buckinghamshire, HP18 0PZ Aylesbury 1.5 miles (Marylebone 55 mins.), Thame 10 miles, Milton Keynes 18 miles (Distances approx.) RIDGE VIEW, 1 FLEET MARSTON COTTAGES, FLEET MARSTON, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE HP18 0PZ A REFURBISHED COTTAGE EXTENDED OVER TIME TO NOW PROVIDE SIZEABLE ACCOMMODATION IN A QUARTER OF AN ACRE PLOT. RURAL LOCATION WITH FAR REACHING VIEWS JUST TWO MILES FROM AYLESBURY AND FIVE MINUTES FROM AYLESBURY VALE PARKWAY STATION. WADDESDON SCHOOL CATCHMENT Entrance Hall, Large Open Plan Sitting Room, Wonderful Garden Room, Kitchen/Dining Room, Cloakroom, Utility Room, Master Bedroom with Dressing Area and Bathroom, Three Further Double Bedrooms, Family Bathroom, Driveway Parking, Garage, Large Garden Backing onto Countryside Guide Price £485,000 Freehold LOCATION DESCRIPTION Marston comes from the words ‘Mersc and Tun’ meaning Marsh Ridge View is situated in a rural location with open countryside to the Farm. The epithet Fleet refers to a ‘Fleet’ of Brackish water. rear and superb views. The property dates from the late 1900’s and Fleet Marston is a small hamlet of houses either side of the A41 near has been greatly extended over the years, the most recent addition an Aylesbury with an early fourteenth century church. Although excellent garden room which really opens up the ground floor. The slightly larger now ‘Magna Britannia’ from 1806 states only 22 accommodation is very well presented, the current owners having inhabitants living in four houses. Waddesdon (2 ½ miles) has a shop undertaken refurbishment throughout. In the entrance hall are for day to day needs or alternatively Aylesbury is also 2 miles, with floorboards and the staircase, off to the side a cloakroom. -

Historic Walk-Thame-U3A-Draft 4

Historic Walk – Thame & District U3A This rural walk along the River Thame passes through a number of villages of historical interest and visits the 15th century architectural gems of Rycote Chapel and Waterstock Mill. Starting at the church at Shabbington in Buckinghamshire the route soon crosses the River Thame into Oxfordshire and follows the river, before crossing the old railway line to reach Rycote Chapel. From Rycote the route follows an undulating track to Albury and then on to Tiddington. Heading south in Tiddington the route circles west to cross the railway line again before arriving at Waterstock via the golf course. Here there is an opportunity to visit the old mill before returning via the 17th century bridge at Ickford and back into Buckinghamshire. The small hamlet of Little Ickford is the last port of call before returning across the fields to Shabbington. In winter the conditions underfoot can be muddy and in times of flood parts of the route are impassable. Walk Length The main walk (Walk A) is just over 8.5 miles (13.8 km) long (inclusive of two detours to Rycote Chapel and Waterstock Mill) and is reasonably flat. At a medium walking pace this should take 3.5 to 4 hours but time needs to be added on to appreciate the points of interest along the way. Walk B is 5.8 miles (9.4 km) a shorter version of Walk A, missing out some of Tiddington and Waterstock. Walk C is another shorter variation of 4.7 miles (7.5 km), taking in Ickford Bridge, Albury and Waterstock but missing out Rycote Chapel and Shabbington. -

Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire Later Bronze Age and Iron Age Historic Environment Resource Assessment Sandy Kidd June 2007 Nature of the evidence The Sites and Monuments Records for Buckinghamshire and Milton Keynes attributes 1622 records (monuments and find spots) to the Iron Age and a further 144 records to the Middle or Late Bronze Age representing about 9.4% of total SMR records. Also, many formally undated cropmark sites probably actually date to the Bronze Age or Iron Age. In addition evidence for the survival of putatively prehistoric landscapes into modern times needs to be considered (see landscape section). Later prehistoric sites have been recognised in Buckinghamshire since the 19 th century with useful summaries of the state of knowledge at the beginning of the twentieth century being provided by the Royal Commission for Historical Monuments and Victoria County History. Essentially knowledge was restricted to a few prominent earthwork monuments and a handful of distinctive finds, mostly from the Chilterns and Thames (Clinch, 1905; RCHME, 1912 & 1913). By 1955 Jack Head was able to identify a concentration of Iron Age hillforts, settlement sites and finds along the Chiltern scarp along with a few sites (mainly hillforts) on the dipslope and a scattering of sites along the Thames. A few of these sites, notably Bulstrode and Cholesbury Camps and an apparently open settlement on Lodge Hill, Saunderton had been investigated by trial trenching (Head, 1955, 62-78). By 1979 it was possible to draw upon a wider range of evidence including modern excavations, aerial photography and environmental archaeology referring to sites in the Ouse valley as well as the Chilterns, open settlements as well as hillforts and evidence for extensive open grassland environments from the Bronze Age onwards (Reed, 1979, 35-41). -

Field View, Sherriff Cottages, Quainton Road, Waddesdon

Field View, Sherriff Cottages, Quainton Road, Waddesdon, Buckinghamshire, HP18 0LT Aylesbury 5 miles (Marylebone 55 mins), Thame 9 miles (Distances approx.) FIELD VIEW, SHERRIFF COTTAGES, QUAINTON ROAD, WADDESDON, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE, HP18 0LT A BRAND NEW HOUSE AT THE EDGE OF THE VILLAGE SIDING ONTO THE COUNTRYSIDE WITH GREAT VIEWS. HELP TO BUY AVAILABLE. Hall, Sitting Room, Kitchen/Dining Room, Cloakroom, Utility Room, Four Bedrooms, Family Bathroom. Driveway for 3 Vehicles. Rear Patio & Lawn. 10 Year Structural Warranty GUIDE PRICE 425,000 Freehold LOCATION In the ancient division of the county, Waddesdon Parish was of great Oxford. The village itself offers a Convenience Store, Coffee Shop, extent. The name is a combination of a person’s name and ‘ DUN’ Hairdressers Salon, Barbers, a Post Office, a Doctor’s Surgery, in old English, translating to Wotts Hill. The village is steeped in Dentist, Vet, Pubs, the Five Arrows Hotel and an Indian Restaurant. history, a large account is written in ‘MAGNA BRITTANNIA’ in There are also tennis and bowls clubs. 1806 concerning its famous connections. There is a church of Norman origins and the old Roman Military Road, Akeman Street Aylesbury is about 5miles with the Aylesbury Vale Parkway station used to pass through the place. A branch of the Aylesbury and providing frequent service to Marylebone, just a five minute drive Tring silk manufactory was established in the village in 1843 away in Fleet Marston/Berryfields. Haddenham/Thame Parkway employing some 40 females at hand loom weaving but has long station is about 8 miles away, providing rail links to London and since gone. -

ED131 Land East of Buckingham Road

Mr Nick Freer Our Ref: APP/J0405/A/14/2219574 David Lock Associates Ltd 50 North Thirteenth Street Central Milton Keynes MK9 3BP 9 August 2016 Dear Sir TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 – SECTION 78 APPEAL BY HALLAM LAND MANAGEMENT LTD: LAND EAST OF A413 BUCKINGHAM ROAD AND WATERMEAD, AYLESBURY APPLICATION REF: 13/03534/AOP 1. I am directed by the Secretary of State to say that consideration has been given to the report of the Inspector, David M H Rose BA (Hons) MRTPI, who held an inquiry for 13 days between 4 November 2014 and 21 July 2015 into your client’s appeal against a refusal to grant outline planning permission by Aylesbury Vale District Council (‘the Council’) for up to 1,560 dwellings, together with a primary school, nursery, a mixed use local centre for retail, employment, healthcare and community uses, green infrastructure and new link road, in accordance with application reference 13/03534/AOP, dated 17 December 2013. 2. On 6 June 2014 the appeal was recovered for the Secretary of State's determination, in pursuance of section 78 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, because the appeal involves proposals for residential development of over 150 units or on sites of over 5 hectares, which would significantly impact on the Government’s objective to secure a better balance between housing demand and supply and create high quality, sustainable, mixed and inclusive communities. Inspector’s recommendation and summary of the decision 3. The Inspector recommends that the appeal be dismissed. For the reasons given below, the Secretary of State agrees with the Inspector’s conclusions and recommendation, dismisses the appeal and refuses planning permission. -

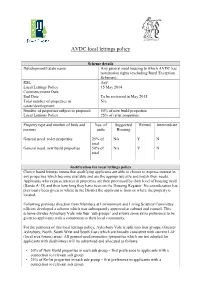

AVDC Sub Groups Local Lettings Policy

AVDC local lettings policy Scheme details Development/Estate name Any general need housing to which AVDC has nomination rights (excluding Rural Exception Schemes). RSL Any Local Lettings Policy – 15 May 2014 Commencement Date End Date To be reviewed in May 2015 Total number of properties in N/a estate/development Number of properties subject to proposed 50% of new build properties Local Lettings Policy 25% of re let properties Property type and number of beds and Nos. of Supported Rented Intermediate persons units Housing General need, re-let properties 25% of N/a Y N total General need, new build properties 50% of N/a Y N total Justification for local lettings policy Choice based lettings means that qualifying applicants are able to choose to express interest in any properties which become available and are the appropriate size and match their needs. Applicants who express interest in properties are then prioritised by their level of housing need (Bands A- D) and then how long they have been on the Housing Register. No consideration has previously been given to where in the District the applicant is from or where the property is located. Following previous direction from Members at Environment and Living Scrutiny Committee officers developed a scheme which was subsequently approved at cabinet and council. This scheme divides Aylesbury Vale into four ‘sub groups’ and allows some extra preference to be given to applicants with a connection to their local community. For the purposes of this local lettings policy, Aylesbury Vale is split into four groups, (Greater Aylesbury, North, South West and South East) which are broadly consistent with current LAF (local area forum) areas. -

17 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

17 bus time schedule & line map 17 Aylesbury - Fairford Leys - Buckingham Park - View In Website Mode Atylesbury The 17 bus line (Aylesbury - Fairford Leys - Buckingham Park - Atylesbury) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Aylesbury: 7:35 AM - 7:25 PM (2) Bicester: 6:40 PM (3) Bicester Town Centre: 6:33 AM - 5:15 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 17 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 17 bus arriving. Direction: Aylesbury 17 bus Time Schedule 46 stops Aylesbury Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:35 AM - 7:25 PM Manorsƒeld Road, Bicester Town Centre Manorsƒeld Road, Bicester Tuesday 7:35 AM - 7:25 PM Clifton Close, Bicester Wednesday 7:35 AM - 7:25 PM Granville Way, Bicester Thursday 7:35 AM - 7:25 PM Friday 7:35 AM - 7:25 PM Retail Park, Bicester Saturday 7:55 AM - 7:25 PM Bicester Road, Glory Farm Telford Road, Bicester Civil Parish Post O∆ce, Launton 17 bus Info The Bull Inn, Launton Direction: Aylesbury Stops: 46 Tomkins Lane, Marsh Gibbon Trip Duration: 40 min Line Summary: Manorsƒeld Road, Bicester Town West Edge, Marsh Gibbon Centre, Clifton Close, Bicester, Granville Way, Bicester, Retail Park, Bicester, Bicester Road, Glory Farm, Post Ware Leys Close, Marsh Gibbon Civil Parish O∆ce, Launton, The Bull Inn, Launton, Tomkins Lane, The Plough Ph, Marsh Gibbon Marsh Gibbon, West Edge, Marsh Gibbon, The Plough Ph, Marsh Gibbon, Castle Street, Marsh Castle Street, Marsh Gibbon Gibbon, Buckingham Road, Edgcott, Grendon Road, Edgcott, Prison Gates, Springhill, -

Roman Buckinghamshire- Draft R J Zeepvat & D Radford

Roman Buckinghamshire- Draft R J Zeepvat & D Radford Nature of the Evidence Base Most of the written record for Roman Buckinghamshire has either been published in the county journal, Records of Buckinghamshire , or in the Buckinghamshire Archaeological Society Monograph Series , which contains reports on the work of the Milton Keynes Archaeology Unit. More recent, post-1991 PPG16-related work is summarised in South Midlands Archaeology , and also in Records . More detailed reports on the latter resides as grey literature within the County SMR, alongside a wealth of unpublished fieldwalking data and miscellaneous small-scale works undertaken by the former county unit and various local societies. Buckinghamshire does not present itself as a logical unit of study for this period, so the absence of countywide studies of Roman archaeology is not surprising. The most readily accessible summary of the county’s Roman archaeology is to be found in The Buckinghamshire Landscape (Reed 1979, 42-52). A number of more localised studies deal with more topographically coherent areas; The Chilterns (Branigan 1967; Branigan 1971a; Branigan 1973a; Branigan and Niblett 2003; Hepple and Doggett 1994) the Ouse valley (Green 1956; Zeepvat 1987; Dawson 2000), the Chess valley (Branigan 1967) and the Milton Keynes area (Zeepvat 1991a & 1991b; Zeepvat 1993b). The civitas Catuvellaunorum , the Roman administrative unit that includes the present county of Buckinghamshire, has been described by Branigan (1987). Buckinghamshire’s more readily identifiable Roman sites attracted a number of 19 th and early 20 th -century investigations. Several substantial Roman villas, such as Tingewick (Roundell 1862) and Yewden villa, Hambledon (Cocks 1921), were excavated during this period. -

BUCKINGHAMSHIRE POSSE COMITATUS 1798 the Posse Comitatus, P

THE BUCKINGHAMSHIRE POSSE COMITATUS 1798 The Posse Comitatus, p. 632 THE BUCKINGHAMSHIRE POSSE COMITATUS 1798 IAN F. W. BECKETT BUCKINGHAMSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY No. 22 MCMLXXXV Copyright ~,' 1985 by the Buckinghamshire Record Society ISBN 0 801198 18 8 This volume is dedicated to Professor A. C. Chibnall TYPESET BY QUADRASET LIMITED, MIDSOMER NORTON, BATH, AVON PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY ANTONY ROWE LIMITED, CHIPPENHAM, WILTSHIRE FOR THE BUCKINGHAMSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY CONTENTS Acknowledgments p,'lge vi Abbreviations vi Introduction vii Tables 1 Variations in the Totals for the Buckinghamshire Posse Comitatus xxi 2 Totals for Each Hundred xxi 3-26 List of Occupations or Status xxii 27 Occupational Totals xxvi 28 The 1801 Census xxvii Note on Editorial Method xxviii Glossary xxviii THE POSSE COMITATUS 1 Appendixes 1 Surviving Partial Returns for Other Counties 363 2 A Note on Local Military Records 365 Index of Names 369 Index of Places 435 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The editor gratefully acknowledges the considerable assistance of Mr Hugh Hanley and his staff at the Buckinghamshire County Record Office in the preparation of this edition of the Posse Comitatus for publication. Mr Hanley was also kind enough to make a number of valuable suggestions on the first draft of the introduction which also benefited from the ideas (albeit on their part unknowingly) of Dr J. Broad of the North East London Polytechnic and Dr D. R. Mills of the Open University whose lectures on Bucks village society at Stowe School in April 1982 proved immensely illuminating. None of the above, of course, bear any responsibility for any errors of interpretation on my part. -

44 Sharp's Close, Waddesdon, Buckinghamshire, HP18

44 Sharp’s Close, Waddesdon, Buckinghamshire, HP18 0LZ Aylesbury 5 miles (Marylebone 55 mins), Thame 9 miles (Distances approx.) 44 SHARP’S CLOSE, WADDESDON, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE, HP18 0LZ A 1950’s HOUSE AT THE END OF A CUL DE SAC BACKING ONTO ALLOTMENTS WITH OPEN VIEWS. GREAT POTENTIAL TO EXTEND THE ACCOMMODATION AND GOOD SIZE GARDEN Sitting Room, Kitchen/Dining Room, Side Passage & Shed/Workshop, Three Bedrooms, Family Bathroom. Driveway for 3 vehicles and potential for further parking. Over 50ft Rear Garden GUIDE PRICE £375,000 Freehold DESCRIPTION These ex local authority properties are extremely popular not least because they are so sturdily built and often enjoy good size plots, and 44 Sharp’s Close is no exception with over a 50ft garden backing onto Rothschild land and a lovely outlook. The elevations of the house are brick beneath a tiled roof with upvc double glazed windows. At the entrance is a porch canopy and upvc double glazed door that has patterned glass panels, this leads into the sitting room where the staircase can be found. Currently in the fireplace is an electric fire but we believe behind that is a working fireplace that could be brought back into life. The kitchen and dining room are open plan partially separated by a breakfast bar. The kitchen has wooden fronted units and wooden effect worktops that incorporate a stainless steel sink. There are spaces for appliances and plumbing for both a washing machine and dishwasher and integrated is an oven and a 4 ring halogen hob. There are more cupboards, one under the stairs and others either side of the chimney breast in the dining area where there is another fireplace waiting to be utilised. -

Archaeological Services & Consultancy

Archaeological Services & Consultancy Ltd ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION: SPICER HALLFIELD SITE BANKS ROAD HADDENHAM BUCKINGHAMSHIRE NGR: SP 7416 2278 on behalf of W.E. Black Ltd. Jonathan R Hunn BA PhD MIFA July 2010 ASC: 1304/HBR/2 Letchworth House Chesney Wold, Bleak Hall Milton Keynes MK6 1NE Tel: 01908 608989 Fax: 01908 605700 Email: [email protected] Website: www.archaeological-services.co.uk Spicer-Hallfield, Banks Road, Haddenham, Buckinghamshire Evaluation Report 1304/HBR Site Data ASC project code: HBR ASC project no: 1304 OASIS ref: Archaeol2-79141 Event/Accession no: tbc County: Buckinghamshire Village/Town: Haddenham Civil Parish: Haddenham NGR (to 8 figs): SP 7416 2278 Extent of site: c.11500 sq. m. Present use: Disused (formerly industrial) Planning proposal: Residential redevelopment Planning application ref/date: 07/03507/AOP: 10/00757/AOP Local Planning Authority: Aylesbury Vale District Council Date of fieldwork: 23rd June 2010 Client: W.E. Black Ltd Hawridge Place Hawridge Chesham Bucks HP5 2UG Contact name: Eric Gadsden Internal Quality Check Primary Author: Jonathan R Hunn Date: 8th July 2010 Revisions: Date: Edited/Checked By: Bob Zeepvat [signed] Date: 8th July 2010 © Archaeological Services & Consultancy Ltd No part of this document is to be copied in any way without prior written consent. Every effort is made to provide detailed and accurate information. However, Archaeological Services & Consultancy Ltd cannot be held responsible for errors or inaccuracies within this report. © Ordnance Survey maps reproduced with the sanction of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. ASC Licence No. AL 100015154 © ASC Ltd 2010 Page 1 Spicer-Hallfield, Banks Road, Haddenham, Buckinghamshire Evaluation Report 1304/HBR CONTENTS Summary.................................................................................................................................... -

Proceedings W Esley Historical Society

Proceedings OF THE W esley Historical Society Editor: REv. JOHN C. BOWMER, M.A., B.D., Ph.D. Volume XL February 1975 EDITORIAL O have reached volume xl is, on any account, something of note, especially when it is remembered that these volumes Tcover the best part of eighty years' continuous publication. During that period, magazines and journals of all kinds have come and gone (particularly in Methodism), so that survival itself is an achievement. Nor is mere survival a matter for congratulation: we are grateful that we flourish as well as survive. We have never lacked contributions of a quality befitting what we like to regard as a " learned " journal, and to all contributors we are indeed grateful. As a society, we have not reached our aim of I,ooo members yet, but new members are replacing deaths and resignations, so that we have maintained a steady figure of about nine hundred. The work of our Branches is commendable, for it supplies a meas ure of contact between members which is impossible within the bounds of the parent Society. Their bulletins continue to be excel lent exercises in local history. We also note with great satisfaction the success of the Conference organized by the World Methodist Historical Society. Interest in Wesley studies shows no sign of diminishing, but per haps the most significant developments are in the outworkings of Methodism in the nineteenth century. This is reflected in articles which have appeared in these Proceedings during recent years. As, therefore, we embark on this fortieth volume, we proceed (forgive the pun !) with hope.