Spaces for Becomings? Heterotopic Fictions in Preciado's Testo Yonqui

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

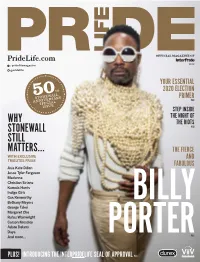

Why Stonewall Still Matters…

PrideLife Magazine 2019 / pridelifemagazine 2019 @pridelife YOUR ESSENTIAL th 2020 ELECTION 50 PRIMER stonewall P.68 anniversaryspecial issue STEP INSIDE THE NIGHT OF WHY THE RIOTS STONEWALL P.50 STILL MATTERS… THE FIERCE WITH EXCLUSIVE AND TRIBUTES FROM FABULOUS Asia Kate Dillon Jesse Tyler Ferguson Madonna Christian Siriano Kamala Harris Indigo Girls Gus Kenworthy Bethany Meyers George Takei BILLY Margaret Cho Rufus Wainwright Carson Kressley Adore Delano Daya And more... PORTERP.46 PLUS! INTRODUCING THE INTERPRIDELIFE SEAL OF APPROVAL P.14 B:17.375” T:15.75” S:14.75” Important Facts About DOVATO Tell your healthcare provider about all of your medical conditions, This is only a brief summary of important information about including if you: (cont’d) This is only a brief summary of important information about DOVATO and does not replace talking to your healthcare provider • are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed. Do not breastfeed if you SO MUCH GOES about your condition and treatment. take DOVATO. You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should ° You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should HIV-1 to your baby. Know about DOVATO? INTO WHO I AM If you have both human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) and ° One of the medicines in DOVATO (lamivudine) passes into your breastmilk. hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, DOVATO can cause serious side ° Talk with your healthcare provider about the best way to feed your baby. -

(In)Attention, Listening to Noise

InVisible Culture Cultivating (In)attention, Listening to Noise Emily Bock Published on: Apr 25, 2021 DOI: 10.47761/494a02f6.eb27df12 License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0) InVisible Culture Cultivating (In)attention, Listening to Noise Featured image: Chantal Regnault, Legendary Voguer Willi Ninja wearing a Thierry Mugler body piece, 1989. Photo courtesy of the photographer. 2 InVisible Culture Cultivating (In)attention, Listening to Noise For twenty-five centuries, Western knowledge has tried to look upon the world. It has failed to understand that the world is not for the beholding. It is for hearing. It is not legible, but audible. — Jacques Attali, Noise: The Political Economy of Music You’ve been invited to a ball. A friend texted you the flier earlier in the day with the address and descriptions of the categories and promises they will be there “on time” (a promise you know they won’t keep). When you arrive, a little before Legends, Statements, and Stars, you meander around the room looking for your friends’ house table to put down the few things you’ve brought along with you to survive the long evening (wallet, keys, phone, lipstick) and talk to folks about things neither of you will remember tomorrow. You won’t remember, not because the conversation is lacking in wit and energy; the opposite really. Everyone around you is laughing loudly, slapping knees and hands together in exclamation. It seems as though the room is talking over each other with such speed and enthusiasm that you can barely focus on your own words as they spill out into the large room which only seems to get smaller as more and more people flood in from the outside. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading Rupaul's Drag Race

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading RuPaul’s Drag Race: Queer Memory, Camp Capitalism, and RuPaul’s Drag Empire A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Carl Douglas Schottmiller 2017 © Copyright by Carl Douglas Schottmiller 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reading RuPaul’s Drag Race: Queer Memory, Camp Capitalism, and RuPaul’s Drag Empire by Carl Douglas Schottmiller Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor David H Gere, Chair This dissertation undertakes an interdisciplinary study of the competitive reality television show RuPaul’s Drag Race, drawing upon approaches and perspectives from LGBT Studies, Media Studies, Gender Studies, Cultural Studies, and Performance Studies. Hosted by veteran drag performer RuPaul, Drag Race features drag queen entertainers vying for the title of “America’s Next Drag Superstar.” Since premiering in 2009, the show has become a queer cultural phenomenon that successfully commodifies and markets Camp and drag performance to television audiences at heretofore unprecedented levels. Over its nine seasons, the show has provided more than 100 drag queen artists with a platform to showcase their talents, and the Drag Race franchise has expanded to include multiple television series and interactive live events. The RuPaul’s Drag Race phenomenon provides researchers with invaluable opportunities not only to consider the function of drag in the 21st Century, but also to explore the cultural and economic ramifications of this reality television franchise. ii While most scholars analyze RuPaul’s Drag Race primarily through content analysis of the aired television episodes, this dissertation combines content analysis with ethnography in order to connect the television show to tangible practices among fans and effects within drag communities. -

Clik-0701-Compressed.Pdf

MAG A Z N E EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Dwight S. Powell [email protected] MANAGING EDITOR Luis A. Medrano GRAPHIC DESIGNER Lorenzo Turner Atlanta,GA DEPARTMENT WRITERS / DIRECTORS Fashion Curtis Davis NewYork,NY Finance/Money Jirard Von Washington Miami,FL Travel Feature Michael Adams Atlanta,GA Ball Culture Frank Leon Roberts NewYork, NY Brave Soul Collective Tim'm West WashingtonDC Brave Soul Collective Monte Wolf WashingtonDC FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER Photographer Effi Cohen NewYork Photographer Aeric Meredith-Goujon NewYork Photographer Ricc Rollins Tampa,FL STAFF WRITERS Senior Staff Writer Scott Bogan Atlanta,GA Senior Staff Writer Darryl Moch PhoenixA, l Senior Staff Writer Craig Washington Atlanta,GA Staff Writer Michael Rochelle Baltimore,MD Staff Writer Herndon Davis LosAngelos,CA Staff Writer Juwan Watson Portage,MI Staff Writer Kevin McNeir Chicago,IL Staff Writer Lloyd Dinwiddie Atlanta.GA Staff Writer Clay Cane JerseyCity,NJ Staff Writer Darian Aaron Atlanta,GA CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Ricc Rollins Keith Boykin Jasmyne Connick Ramon Johnson ADVERTISING DEPARTMENT I Ad Sales: 404-885-6067 DISTRIBUTOR I Ingram Periodicals Inc - 615-793-5522 / ACCOUNT10 54800 SUBSCRIPTIONS / CONTACT [email protected] 1170 Peachtree Street NE, Suite 1200, Atlanta, GA 30309 Visit Us Online At - www.clikmagazine.com ClIKTM Magazine is published monthly by Clik Publications, a Florida corporation. The articles and opinions expressed herein are solely those of their authors and are not necessarily endorsed by ClIKTM Magazine. Namesand pictures of personsappearing in CLlKTMMagazine are no indication of sexual orientation. All persons appear- ing in ClIKTM Magazine are at least 18 years of age. ClIKTM Magazine unless specified, does not endorse and is not responsible for claims and practices of advertisers. -

Sorted by Artist Music Listing 2005 112 Hot & Wet (Radio)

Sorted by Artist Music Listing 2005 112 Hot & Wet (Radio) WARNING 112 Na Na Na (Super Clean w. Rap) 112 Right Here For You (Radio) (63 BPM) 311 First Straw (80 bpm) 311 Love Song 311 Love Song (Cirrus Club Mix) 702 Blah Blah Blah Blah (Radio Edit) 702 Star (Main) .38 Special Fade To Blue .38 Special Hold On Loosely 1 Giant Leap My Culture (Radio Edit) 10cc I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 2 Bad Mice Bombscare ('94 US Remix) 2 Skinnee J's Grow Up [Radio Edit] 2 Unlimited Do What's Good For Me 2 Unlimited Faces 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This 2 Unlimited Here I Go 2 Unlimited Jump For Joy 2 Unlimited Let The Beat Control Your Body 2 Unlimited Magic Friend 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited No Limit 2 Unlimited No One 2 Unlimited Nothing Like The Rain 2 Unlimited Real Thing 2 Unlimited Spread Your Love 2 Unlimited Tribal Dance 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2 Unlimited Unlimited Megajam 2 Unlimited Workaholic 2% of Red Tide Body Bagger 20 Fingers Lick It 2funk Apsyrtides (original mix) 2Pac Thugz Mansion (Radio Edit Clean) 2Pac ft Trick Daddy Still Ballin' (Clean) 1 of 197 Sorted by Artist Music Listing 2005 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun (67 BPM) 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down Here Without You (Radio Edit) 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Road I'm On 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3k Static Shattered 3LW & P Diddy I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW ft Diddy & Loan I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW ft Lil Wayne Neva Get Enuf 4 Clubbers Children (Club Radio Edit) 4 Hero Mr. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist - Human Metallica (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace "Adagio" From The New World Symphony Antonín Dvorák (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew "Ah Hello...You Make Trouble For Me?" Broadway (I Know) I'm Losing You The Temptations "All Right, Let's Start Those Trucks"/Honey Bun Broadway (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (Reprise) (I Still Long To Hold You ) Now And Then Reba McEntire "C" Is For Cookie Kids - Sesame Street (I Wanna Give You) Devotion Nomad Feat. MC "H.I.S." Slacks (Radio Spot) Jay And The Mikee Freedom Americans Nomad Featuring MC "Heart Wounds" No. 1 From "Elegiac Melodies", Op. 34 Grieg Mikee Freedom "Hello, Is That A New American Song?" Broadway (I Want To Take You) Higher Sly Stone "Heroes" David Bowie (If You Want It) Do It Yourself (12'') Gloria Gaynor "Heroes" (Single Version) David Bowie (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here! Shania Twain "It Is My Great Pleasure To Bring You Our Skipper" Broadway (I'll Be Glad When You're Dead) You Rascal, You Louis Armstrong "One Waits So Long For What Is Good" Broadway (I'll Be With You) In Apple Blossom Time Z:\MUSIC\Andrews "Say, Is That A Boar's Tooth Bracelet On Your Wrist?" Broadway Sisters With The Glenn Miller Orchestra "So Tell Us Nellie, What Did Old Ironbelly Want?" Broadway "So When You Joined The Navy" Broadway (I'll Give You) Money Peter Frampton "Spring" From The Four Seasons Vivaldi (I'm Always Touched By Your) Presence Dear Blondie "Summer" - Finale From The Four Seasons Antonio Vivaldi (I'm Getting) Corns For My Country Z:\MUSIC\Andrews Sisters With The Glenn "Surprise" Symphony No. -

Performing Gay Identities Online

Qualitative Inquiry http://qix.sagepub.com Sober Drag Queens, Digital Forests, and Bloated "Lesbians": Performing Gay Identities Online Ragan Fox Qualitative Inquiry 2008; 14; 1245 DOI: 10.1177/1077800408321719 The online version of this article can be found at: http://qix.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/14/7/1245 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Qualitative Inquiry can be found at: Email Alerts: http://qix.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://qix.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://qix.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/14/7/1245 Downloaded from http://qix.sagepub.com at CALIF STATE UNIV LONG BEACH on October 14, 2008 Qualitative Inquiry Volume 14 Number 7 October 2008 1245-1263 © 2008 Sage Publications Sober Drag Queens, Digital 10.1177/1077800408321719 http://qix.sagepub.com hosted at Forests, and Bloated http://online.sagepub.com “Lesbians” Performing Gay Identities Online Ragan Fox California State University, Long Beach This essay focuses on how gay podcasters, or “Qpodders,” perform their iden- tities in “soundscape” environments. Most of the “data” presented in the report take the form of poetry, dramatic monologue, and dramatic dialogue. Using creative reporting strategies, I chronicle how Qpodders record the ambient sounds of the scenes in which they are embedded; and, as a result, I argue that, within the context of a podcast, nonverbal sounds are poetic and narrate. Keywords: gay; identity; podcasting; soundscapes n September 28, 2005, gay podcaster Richard Bluestein attended the Ofirst annual Podcast and Portable Media Expo in Ontario, California. -

Photographic Journal

nl14_1:nl14_1 10/7/09 6:27 AM Page fc1 NUEVALUZ photographic journal GERARD H. GASKIN MUEMA LOMBE &LORIE CAVAL PRADEEP DALAL ELIA ALBA RYAN JOSEPH Volume 14 No. 1 – U.S. $7.00 GUEST EDITED BY EDWIN RAMORAN INTERCAMBIO: Changing the Art World BY LISA HENRY nl14_1:nl14_1 10/7/09 6:27 AM Page fc2 Jacob K. Javits Convention Center • October 22-24, 2009 • New York City The Most Important Event in FREE EXPO PASS the Photography and Imaging REGISTER TODAY! HURRY, OFFER Industries For Over 25 Years EXPIRES 10/8/09 Don’t miss PDN PhotoPlus Expo 2009! The premier event for photography and imaging professionals. Huge Expo Floor, Hundreds of Exhibitors, Thousands of New Products PhotoPlus Expo is your #1 source for the latest technologies and hottest products in photography. Exhibitors this year include Nikon, Canon, Hewlett Packard, Epson, Sony, Olympus, Leica and more! And admission to the Expo floor is FREE. Over 100 Seminars, Special Events and Hands-On Workshops Learn from and be inspired by some of the greatest photographers and imaging experts in the world. Go to www.photoplusexpo.com to see the schedule and session descriptions and enroll now. New this year! The PDN PhotoPlus Expo Bash Reserve your ticket today! Business owners, for information on exhibiting at the Expo, e-mail [email protected] Come see seminar presenter Rodney Smith in person at the 2009 PhotoPlus Expo! IMAGE © RODNEY SMITH Beat the Crowds! Experience the Show as a VIP The 2009 Gold Expo Pass is an exclusive 3-day pass that includes: • Exclusive early access to -

DJ Music Catalog by Title

Artist Title Artist Title Artist Title Dev Feat. Nef The Pharaoh #1 Kellie Pickler 100 Proof [Radio Edit] Rick Ross Feat. Jay-Z And Dr. Dre 3 Kings Cobra Starship Feat. My Name is Kay #1Nite Andrea Burns 100 Stories [Josh Harris Vocal Club Edit Yo Gotti, Fabolous & DJ Khaled 3 Kings [Clean] Rev Theory #AlphaKing Five For Fighting 100 Years Josh Wilson 3 Minute Song [Album Version] Tank Feat. Chris Brown, Siya And Sa #BDay [Clean] Crystal Waters 100% Pure Love TK N' Cash 3 Times In A Row [Clean] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful Frenship 1000 Nights Elliott Yamin 3 Words Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful [Louie Vega EOL Remix - Clean Rachel Platten 1000 Ships [Single Version] Britney Spears 3 [Groove Police Radio Edit] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And A$AP #Beautiful [Remix - Clean] Prince 1000 X's & O's Queens Of The Stone Age 3's & 7's [LP] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And Jeezy #Beautiful [Remix - Edited] Godsmack 1000hp [Radio Edit] Emblem3 3,000 Miles Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful/#Hermosa [Spanglish Version]d Colton James 101 Proof [Granny With A Gold Tooth Radi Lonely Island Feat. Justin Timberla 3-Way (The Golden Rule) [Edited] Tucker #Country Colton James 101 Proof [The Full 101 Proof] Sho Baraka feat. Courtney Orlando 30 & Up, 1986 [Radio] Nate Harasim #HarmonyPark Wrabel 11 Blocks Vinyl Theatre 30 Seconds Neighbourhood Feat. French Montana #icanteven Dinosaur Pile-Up 11:11 Jay-Z 30 Something [Amended] Eric Nolan #OMW (On My Way) Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [KBCO Edit] Childish Gambino 3005 Chainsmokers #Selfie Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [Radio Edit] Future 31 Days [Xtra Clean] My Chemical Romance #SING It For Japan Michael Franti & Spearhead Feat. -

Dance Tracks 1973–1997 (From the Ballroom Archive & Oral History Project Interviews)

What IS THE SOUND OF Ballroom? Dance Tracks 1973–1997 (from the Ballroom Archive & Oral History Project interviews) 6 1985 9 10 17 1995 26 1 1975 2 5 13 14 18 21 22 25 3 4 7 19 20 23 24 27 1970 1980 8 11 12 1990 15 16 2000 1 MFSB. Love Is The Message [6:35]. 5 Loose Joints. Is It All Over My Face? / 9 Tyree. Acid Crash / House Mix [6:01]. 13 Bobby Konders. The Poem [8:35]. 17 Soft House Company. ... A Little Piano [6:04]. 21 Armand Van Helden. Witch Doktor [4:04]. 25 Rageous Projecting Kevin Aviance. Cunty Love Is The Message [LP]. New York, NY: Phila- Female Vocal [6:56]. Acid Crash / Red Hot [Promo 12”]. Chicago, IL: House Rhythms [12”]. New York, NY: Nu Groove Re- What You Need ... [12”]. Bologna, Italy : Irma Witch Doktor [12”]. New York, NY: Strictly (The Feeling) / Emma Peele Dub [5:36]. delphia Int’l Records, 1973. Is It All Over My Face? [12”]. New York, NY: House Musik, 1988. cords, 1990. CasaDiPrimordine, 1990. Rhythm, 1994. Cunty (The Feeling) [12”]. New York, NY: Strict- K. Gamble and L. Huff - Producers and Writers; West End Records, 1980. Rodney Baker and Tyree - Producers. Bobby Konders - Producer; Peter Daou - Engineer Umbi Damiani - Producer; C. Rispoli - Writer; Armand Van Helden - Producer and Writer. ly Rhythm, 1996. Bobby Martin - Arranger. Arthur Russell and Steve D’Aquisto - Producers Ballroom category: Butch Queen Performance. and Keyboards. Claudio Rispoli and Kekko Montefiori - Arrangers Ballroom category: Fem Queen or Butch Queen Dra- Kevin Aviance - Performer; Jerel Black - Produc- Ballroom category: Vogue Performance. -

The Fierce Tribe

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2008 The Fierce Tribe Mickey Weems Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Folklore Commons Recommended Citation Weems, M. (2008). The fierce tribe: Masculine identity and performance in the Circuit. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. !"#$%&#'(#$!'&)# ,*&&$-+.')/+0$+12$3456$#*)74*68$999:;4567*)74*6:7<0 !"#$%&'()*+$ !"#$%&#'(#$!'&)# *+,-./012$&3214045$+13$627897:+1-2$ 01$4;2$(07-.04 *0-<25$=22:, Utah State University Press Logan, Utah Copyright ©2008 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 843227200 www.usu.edu/usupress Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on recycled, acidfree paper ISBN: 978–0–87421–691–2 (cloth) ISBN: 978–0–87421–692–9 (ebook) !"#$%&'#($)*+,#$-+.$/.#0$1&$+0'#(1).#$1"#$2(.1$3/+4)+$5+(1)#.$)6$7&4/*8/.9$:")&;$!"#$ original photo is by Ric Brown and Bulldog Productions, www.bulldogproductions.net; design by Kevin Mason. Used by permission. Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data Weems, Mickey. $$!"#$2#(%#$1()8#$<$*+.%/4)6#$)0#61)1=$+60$5#(>&(*+6%#$)6$1"#$7)(%/)1$?$@)%A#=$B##*.; p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 9780874216912 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 9780874216929 (ebook) 1. -

Jungle / Drum&Bass Music

Kim Cascone Aesthe/cs of Failure and Glitch Music – We therefore invite young musicians of talent to conduct a sustained observation of all noises, in order to understand the various rhythms of which they are composed, their principal and secondary tones. By comparing the various tones of noises with those of sounds, they will be convinced of the extent to which the former exceeds the latter. This will afford not only an understanding, but also a taste and passion for noises. — Luigi Russolo (1913) 1 Sunday, December 8, 13 “At some point in the early 1990s, techno music settled into a predictable, formulaic genre serving a more or less aesthetically homogeneous market of DJs and dance music aficionados. Concomitant with this development was the rise of a periphery of DJs and producers eager to expand the music’s tendrils into new areas. One can visualize techno as a large postmodern appropriation machine, assimilating cultural references, tweaking them, and then representing them as tongue-in-cheek jokes. DJs, fueled with samples from thrift store purchases of obscure vinyl, managed to mix any source imaginable into sets played for more adventurous dance floors. Always trying to outdo one another, it was only a matter of time until DJs unearthed the history of electronic music in their archeological thrift store digs. Once the door was opened to exploring the history of electronic music, invoking its more notable composers came into vogue. A handful of DJs and composers of electronica were suddenly familiar with the work of Karlheinz Stockhausen, Morton Subotnick, and John Cage, and their influence helped spawn the glitch movement.” - Kim Cascone, Aesthetics of Failure 2 Sunday, December 8, 13 Glitch Music • Chris/an Marclay • Pansonic / Mika Vainio (Finnish) (1995) • Oval (German) • Ryoji Ikeda (Japanese) • Carsten Nicolai – Noton / Rastermusic 3 Sunday, December 8, 13 IDM • From IDM mailing list on Hyperreal.org and Warp Records Ar/ficial Intelligence Series featuring Aphex Twin, LFO, Autechre etc.