Estimation Des Taux De Mutation : Implications Pour La Diversification Et L'évolution Du Phytoplancton Eucaryote

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aalseth Aaron Aarup Aasen Aasheim Abair Abanatha Abandschon Abarca Abarr Abate Abba Abbas Abbate Abbe Abbett Abbey Abbott Abbs

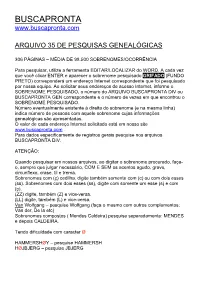

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 35 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 306 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 98.500 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

First Record of Marine Phytoplankton, Picochlorum Maculatum in the Southeastern Coast of India

Indian Journal of Geo Marine Sciences Vol. 46 (04), April 2017, pp. 791-796 First record of marine phytoplankton, Picochlorum maculatum in the Southeastern coast of India Dinesh Kumar, S1. S. Ananth1, P. Santhanam1*, K. Kaleshkumar2 & R. Rajaram2 1Marine Planktonology & Aquaculture Lab., 2DNA Barcoding and Marine Genomics Lab., Department of Marine Science, School of Marine Sciences, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli- 620 024, Tamil Nadu, India. * [E-mail: [email protected], [email protected]] Received 20 October 2014 ; revised 02 January 2015 The marine phytoplankton Picochlorum maculatum (Chlorophyta:Trebouxiophyceae) is recorded for the first time in the Southeastern coast of India. In this study, marine phytoplankton were collected at Muthukkuda mangrove waters, Tamil Nadu, Southeast coast of India which was then isolated, purified and identified with rDNA sequencing. Recurrence component analysis of marine phytoplankton P. maculatum indicated that the peptides were composed of Beta structure, comprising alpha-helix, extended strand and random coil. The number of amino acids and chemical properties from the marine microalgae P. maculatum are calculated and having composition of Neutral (82.69%), Acidic (10.72%) and Basic (6.57%) amino acids. This species may be introduced by way of shipping and other transport mechanisms where organisms are inadvertently moved out of their home range, e.g., ballast water exchange. [Keywords: Microalgae, Picochlorum maculatum, Genetic Distance, Open Reading Frame, Poly A signals] Introduction The genus Picochlorum maculatum was in Indian coastal waters. There are five Picochlorum established by Henley et. al.1 based on Nannochloris were reported in species level from Japan maculta Butcher, 1952. The currently accepted name (Picochlorum atomus, Picochlorum eukaryotum, P. -

Neoproterozoic Origin and Multiple Transitions to Macroscopic Growth in Green Seaweeds

Neoproterozoic origin and multiple transitions to macroscopic growth in green seaweeds Andrea Del Cortonaa,b,c,d,1, Christopher J. Jacksone, François Bucchinib,c, Michiel Van Belb,c, Sofie D’hondta, f g h i,j,k e Pavel Skaloud , Charles F. Delwiche , Andrew H. Knoll , John A. Raven , Heroen Verbruggen , Klaas Vandepoeleb,c,d,1,2, Olivier De Clercka,1,2, and Frederik Leliaerta,l,1,2 aDepartment of Biology, Phycology Research Group, Ghent University, 9000 Ghent, Belgium; bDepartment of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics, Ghent University, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium; cVlaams Instituut voor Biotechnologie Center for Plant Systems Biology, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium; dBioinformatics Institute Ghent, Ghent University, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium; eSchool of Biosciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC 3010, Australia; fDepartment of Botany, Faculty of Science, Charles University, CZ-12800 Prague 2, Czech Republic; gDepartment of Cell Biology and Molecular Genetics, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742; hDepartment of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; iDivision of Plant Sciences, University of Dundee at the James Hutton Institute, Dundee DD2 5DA, United Kingdom; jSchool of Biological Sciences, University of Western Australia, WA 6009, Australia; kClimate Change Cluster, University of Technology, Ultimo, NSW 2006, Australia; and lMeise Botanic Garden, 1860 Meise, Belgium Edited by Pamela S. Soltis, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, and approved December 13, 2019 (received for review June 11, 2019) The Neoproterozoic Era records the transition from a largely clear interpretation of how many times and when green seaweeds bacterial to a predominantly eukaryotic phototrophic world, creat- emerged from unicellular ancestors (8). ing the foundation for the complex benthic ecosystems that have There is general consensus that an early split in the evolution sustained Metazoa from the Ediacaran Period onward. -

Lateral Gene Transfer of Anion-Conducting Channelrhodopsins Between Green Algae and Giant Viruses

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.15.042127; this version posted April 23, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 5 Lateral gene transfer of anion-conducting channelrhodopsins between green algae and giant viruses Andrey Rozenberg 1,5, Johannes Oppermann 2,5, Jonas Wietek 2,3, Rodrigo Gaston Fernandez Lahore 2, Ruth-Anne Sandaa 4, Gunnar Bratbak 4, Peter Hegemann 2,6, and Oded 10 Béjà 1,6 1Faculty of Biology, Technion - Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 32000, Israel. 2Institute for Biology, Experimental Biophysics, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Invalidenstraße 42, Berlin 10115, Germany. 3Present address: Department of Neurobiology, Weizmann 15 Institute of Science, Rehovot 7610001, Israel. 4Department of Biological Sciences, University of Bergen, N-5020 Bergen, Norway. 5These authors contributed equally: Andrey Rozenberg, Johannes Oppermann. 6These authors jointly supervised this work: Peter Hegemann, Oded Béjà. e-mail: [email protected] ; [email protected] 20 ABSTRACT Channelrhodopsins (ChRs) are algal light-gated ion channels widely used as optogenetic tools for manipulating neuronal activity 1,2. Four ChR families are currently known. Green algal 3–5 and cryptophyte 6 cation-conducting ChRs (CCRs), cryptophyte anion-conducting ChRs (ACRs) 7, and the MerMAID ChRs 8. Here we 25 report the discovery of a new family of phylogenetically distinct ChRs encoded by marine giant viruses and acquired from their unicellular green algal prasinophyte hosts. -

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton Hawley III Jamaica Plain, MA M.A., History of Art, Institute of Fine Arts – New York University, 2010 B.A., Art History and History, College of William and Mary, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art and Architectural History University of Virginia May, 2015 _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Life of Cornelis Visscher .......................................................................................... 3 Early Life and Family .................................................................................................................... 4 Artistic Training and Guild Membership ...................................................................................... 9 Move to Amsterdam ................................................................................................................. -

The Low Countries. Jaargang 11

The Low Countries. Jaargang 11 bron The Low Countries. Jaargang 11. Stichting Ons Erfdeel, Rekkem 2003 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_low001200301_01/colofon.php © 2011 dbnl i.s.m. 10 Always the Same H2O Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands hovers above the water, with a little help from her subjects, during the floods in Gelderland, 1926. Photo courtesy of Spaarnestad Fotoarchief. Luigem (West Flanders), 28 September 1918. Photo by Antony / © SOFAM Belgium 2003. The Low Countries. Jaargang 11 11 Foreword ριστον μν δωρ - Water is best. (Pindar) Water. There's too much of it, or too little. It's too salty, or too sweet. It wells up from the ground, carves itself a way through the land, and then it's called a river or a stream. It descends from the heavens in a variety of forms - as dew or hail, to mention just the extremes. And then, of course, there is the all-encompassing water which we call the sea, and which reminds us of the beginning of all things. The English once labelled the Netherlands across the North Sea ‘this indigested vomit of the sea’. But the Dutch went to work on that vomit, systematically and stubbornly: ‘... their tireless hands manufactured this land, / drained it and trained it and planed it and planned’ (James Brockway). As God's subcontractors they gradually became experts in living apart together. Look carefully at the first photo. The water has struck again. We're talking 1926. Gelderland. The small, stocky woman visiting the stricken province is Queen Wilhelmina. Without turning a hair she allows herself to be carried over the waters. -

Neoproterozoic Origin and Multiple Transitions to Macroscopic Growth in Green Seaweeds

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/668475; this version posted June 12, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Neoproterozoic origin and multiple transitions to macroscopic growth in green seaweeds Andrea Del Cortonaa,b,c,d,1, Christopher J. Jacksone, François Bucchinib,c, Michiel Van Belb,c, Sofie D’hondta, Pavel Škaloudf, Charles F. Delwicheg, Andrew H. Knollh, John A. Raveni,j,k, Heroen Verbruggene, Klaas Vandepoeleb,c,d,1,2, Olivier De Clercka,1,2 Frederik Leliaerta,l,1,2 aDepartment of Biology, Phycology Research Group, Ghent University, Krijgslaan 281, 9000 Ghent, Belgium bDepartment of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics, Ghent University, Technologiepark 71, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium cVIB Center for Plant Systems Biology, Technologiepark 71, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium dBioinformatics Institute Ghent, Ghent University, Technologiepark 71, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium eSchool of Biosciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia fDepartment of Botany, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Benátská 2, CZ-12800 Prague 2, Czech Republic gDepartment of Cell Biology and Molecular Genetics, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA hDepartment of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02138, USA. iDivision of Plant Sciences, University of Dundee at the James Hutton Institute, Dundee, DD2 5DA, UK jSchool of Biological Sciences, University of Western Australia (M048), 35 Stirling Highway, WA 6009, Australia kClimate Change Cluster, University of Technology, Ultimo, NSW 2006, Australia lMeise Botanic Garden, Nieuwelaan 38, 1860 Meise, Belgium 1To whom correspondence may be addressed. Email [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] or [email protected]. -

Comparing Relative Rates of Molecular Evolution Between Freshwater and Marine Eukaryotes

ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1111/evo.13000 Do saline taxa evolve faster? Comparing relative rates of molecular evolution between freshwater and marine eukaryotes T. Fatima Mitterboeck,1,2,3 Alexander Y. Chen,1,2 Omar A. Zaheer,1,2 EddieY.T.Ma,1,2,4 and Sarah J. Adamowicz1,2 1Biodiversity Institute of Ontario, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario N1G 2W1, Canada 2Department of Integrative Biology, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario N1G 2W1, Canada 3E-mail: [email protected] 4School of Computer Science, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario N1G 2W1, Canada Received June 8, 2015 Accepted June 28, 2016 The major branches of life diversified in the marine realm, and numerous taxa have since transitioned between marine and freshwaters. Previous studies have demonstrated higher rates of molecular evolution in crustaceans inhabiting continental saline habitats as compared with freshwaters, but it is unclear whether this trend is pervasive or whether it applies to the marine environment. We employ the phylogenetic comparative method to investigate relative molecular evolutionary rates between 148 pairs of marine or continental saline versus freshwater lineages representing disparate eukaryote groups, including bony fish, elasmobranchs, cetaceans, crustaceans, mollusks, annelids, algae, and other eukaryotes, using available protein-coding and noncoding genes. Overall, we observed no consistent pattern in nucleotide substitution rates linked to habitat across all genes and taxa. However, we observed some trends of higher evolutionary rates within protein-coding genes in freshwater taxa—the comparisons mainly involving bony fish—compared with their marine relatives. The results suggest no systematic differences in substitution rate between marine and freshwater organisms. -

UNDERSTANDING the GENOMIC BASIS of STRESS ADAPTATION in PICOCHLORUM GREEN ALGAE by FATIMA FOFLONKER a Dissertation Submitted To

UNDERSTANDING THE GENOMIC BASIS OF STRESS ADAPTATION IN PICOCHLORUM GREEN ALGAE By FATIMA FOFLONKER A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Microbial Biology Written under the direction of Debashish Bhattacharya And approved by _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Understanding the Genomic Basis of Stress Adaptation in Picochlorum Green Algae by FATIMA FOFLONKER Dissertation Director: Debashish Bhattacharya Gaining a better understanding of adaptive evolution has become increasingly important to predict the responses of important primary producers in the environment to climate-change driven environmental fluctuations. In my doctoral research, the genomes from four taxa of a naturally robust green algal lineage, Picochlorum (Chlorophyta, Trebouxiphycae) were sequenced to allow a comparative genomic and transcriptomic analysis. The over-arching goal of this work was to investigate environmental adaptations and the origin of haltolerance. Found in environments ranging from brackish estuaries to hypersaline terrestrial environments, this lineage is tolerant of a wide range of fluctuating salinities, light intensities, temperatures, and has a robust photosystem II. The small, reduced diploid genomes (13.4-15.1Mbp) of Picochlorum, indicative of genome specialization to extreme environments, has resulted in an interesting genomic organization, including the clustering of genes in the same biochemical pathway and coregulated genes. Coregulation of co-localized genes in “gene neighborhoods” is more prominent soon after exposure to salinity shock, suggesting a role in the rapid response to salinity stress in Picochlorum. -

World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency

Supplemental File S1 for the article “World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency” published in BioScience by William J. Ripple, Christopher Wolf, Thomas M. Newsome, Phoebe Barnard, and William R. Moomaw. Contents: List of countries with scientist signatories (page 1); List of scientist signatories (pages 1-319). List of 153 countries with scientist signatories: Albania; Algeria; American Samoa; Andorra; Argentina; Australia; Austria; Bahamas (the); Bangladesh; Barbados; Belarus; Belgium; Belize; Benin; Bolivia (Plurinational State of); Botswana; Brazil; Brunei Darussalam; Bulgaria; Burkina Faso; Cambodia; Cameroon; Canada; Cayman Islands (the); Chad; Chile; China; Colombia; Congo (the Democratic Republic of the); Congo (the); Costa Rica; Côte d’Ivoire; Croatia; Cuba; Curaçao; Cyprus; Czech Republic (the); Denmark; Dominican Republic (the); Ecuador; Egypt; El Salvador; Estonia; Ethiopia; Faroe Islands (the); Fiji; Finland; France; French Guiana; French Polynesia; Georgia; Germany; Ghana; Greece; Guam; Guatemala; Guyana; Honduras; Hong Kong; Hungary; Iceland; India; Indonesia; Iran (Islamic Republic of); Iraq; Ireland; Israel; Italy; Jamaica; Japan; Jersey; Kazakhstan; Kenya; Kiribati; Korea (the Republic of); Lao People’s Democratic Republic (the); Latvia; Lebanon; Lesotho; Liberia; Liechtenstein; Lithuania; Luxembourg; Macedonia, Republic of (the former Yugoslavia); Madagascar; Malawi; Malaysia; Mali; Malta; Martinique; Mauritius; Mexico; Micronesia (Federated States of); Moldova (the Republic of); Morocco; Mozambique; Namibia; Nepal; -

An Investig Atio N of the Anabolic

AN INVESTIGATION OF THE ANABOLIC ACTIONS OF BIOSYNTHETIC HUMAN GROWTH HORMONE AFTER INJURY BY BURNING A thesis sumitted for the degree of MASTER OF SURGERY in the UNIVERSITY OF LONDON H.J.C.R. Belcher, MB, BS(Lond), FRCS(Eng). The Blond-Mclndoe Centre, Queen Victoria Hospital, Holtye Rd, East Grinstead, SUSSEX. - 1 - ProQuest Number: U053257 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest U053257 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 To my wife, Georgina - 2 - ABSTRACT Previous clinical trials in normal subjects and post-operative patients have shown that biosynthetic growth hormone preparations increase nitrogen retention. It has been suggested that their administration to injured patients may be beneficial. A clinical trial is presented of twelve adult burned patients of whom six were allocated to receive biosynthetic human growth hormone (somatropin) and six to form a control group. Injury by burning is followed by increases in resting energy expenditure and urinary nitrogen excretion, accompanied by insulin resistance and glucose intolerance. There is a generalised fall in plasma protein concentrations, including the somatomedin, insulin-like growth factor-I. -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Méheust et al. 10.1073/pnas.1517551113 S-Gene Expression Analysis extracellular domain. This novel protein is found only in green Given that the analysis using dozens of algal and protist genomic algae and plants, and may play a role in responding to salt stress. datasets showed that homologs of all of the S genes are expressed, For S genes present in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum, we asked whether some of them might be differentially expressed we used RNA-seq data from ref. 30 that compared cultures in response to stress. This question was motivated by two ob- grown under control and nitrogen (N)-depleted conditions. This servations: (i) The composite genes entered eukaryote nuclear analysis showed that out of six families present in this alga (2, 1, genomes via primary endosymbiosis, and therefore they may still 28, 20, 35, 61), three are differentially expressed under N stress retain ancient cyanobacterial functions even when fused to novel (28, 35, 61). One of these is family 28, which encodes an domains, and (ii) many of the S genes are redox enzymes or N-terminal bacterium-derived, calcium-sensing EF-hand domain encode domains involved in redox regulation, and therefore their fused, intriguingly, to a cyanobacterium-derived region with sim- roles may involve sensing and/or responding to cellular stress ilarity to the plastid inner-membrane proten import component resulting from the oxygen-evolving photosynthetic organelle. To Tic20, which acts as a translocon channel. This fused protein may + address this issue, we inspected RNA-seq data from organisms use Ca2 as a signal for protein import, and is found in several that encoded particular S genes that had either been generated stramenopile (brown algal) species.