Isolation and Identification of Culturable Fungi from the Genitals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major Clades of Agaricales: a Multilocus Phylogenetic Overview

Mycologia, 98(6), 2006, pp. 982–995. # 2006 by The Mycological Society of America, Lawrence, KS 66044-8897 Major clades of Agaricales: a multilocus phylogenetic overview P. Brandon Matheny1 Duur K. Aanen Judd M. Curtis Laboratory of Genetics, Arboretumlaan 4, 6703 BD, Biology Department, Clark University, 950 Main Street, Wageningen, The Netherlands Worcester, Massachusetts, 01610 Matthew DeNitis Vale´rie Hofstetter 127 Harrington Way, Worcester, Massachusetts 01604 Department of Biology, Box 90338, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708 Graciela M. Daniele Instituto Multidisciplinario de Biologı´a Vegetal, M. Catherine Aime CONICET-Universidad Nacional de Co´rdoba, Casilla USDA-ARS, Systematic Botany and Mycology de Correo 495, 5000 Co´rdoba, Argentina Laboratory, Room 304, Building 011A, 10300 Baltimore Avenue, Beltsville, Maryland 20705-2350 Dennis E. Desjardin Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, Jean-Marc Moncalvo San Francisco, California 94132 Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, Royal Ontario Museum and Department of Botany, University Bradley R. Kropp of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2C6 Canada Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, Utah 84322 Zai-Wei Ge Zhu-Liang Yang Lorelei L. Norvell Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Pacific Northwest Mycology Service, 6720 NW Skyline Sciences, Kunming 650204, P.R. China Boulevard, Portland, Oregon 97229-1309 Jason C. Slot Andrew Parker Biology Department, Clark University, 950 Main Street, 127 Raven Way, Metaline Falls, Washington 99153- Worcester, Massachusetts, 01609 9720 Joseph F. Ammirati Else C. Vellinga University of Washington, Biology Department, Box Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, 111 355325, Seattle, Washington 98195 Koshland Hall, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720-3102 Timothy J. -

Species Recognition in Pluteus and Volvopluteus (Pluteaceae, Agaricales): Morphology, Geography and Phylogeny

Mycol Progress (2011) 10:453–479 DOI 10.1007/s11557-010-0716-z ORIGINAL ARTICLE Species recognition in Pluteus and Volvopluteus (Pluteaceae, Agaricales): morphology, geography and phylogeny Alfredo Justo & Andrew M. Minnis & Stefano Ghignone & Nelson Menolli Jr. & Marina Capelari & Olivia Rodríguez & Ekaterina Malysheva & Marco Contu & Alfredo Vizzini Received: 17 September 2010 /Revised: 22 September 2010 /Accepted: 29 September 2010 /Published online: 20 October 2010 # German Mycological Society and Springer 2010 Abstract The phylogeny of several species-complexes of the P. fenzlii, P. phlebophorus)orwithout(P. ro me lli i) molecular genera Pluteus and Volvopluteus (Agaricales, Basidiomycota) differentiation in collections from different continents. A was investigated using molecular data (ITS) and the lectotype and a supporting epitype are designated for Pluteus consequences for taxonomy, nomenclature and morpho- cervinus, the type species of the genus. The name Pluteus logical species recognition in these groups were evaluated. chrysophlebius is accepted as the correct name for the Conflicts between morphological and molecular delimitation species in sect. Celluloderma, also known under the names were detected in sect. Pluteus, especially for taxa in the P.admirabilis and P. chrysophaeus. A lectotype is designated cervinus-petasatus clade with clamp-connections or white for the latter. Pluteus saupei and Pluteus heteromarginatus, basidiocarps. Some species of sect. Celluloderma are from the USA, P. castri, from Russia and Japan, and apparently widely distributed in Europe, North America Volvopluteus asiaticus, from Japan, are described as new. A and Asia, either with (P. aurantiorugosus, P. chrysophlebius, complete description and a new name, Pluteus losulus,are A. Justo (*) N. Menolli Jr. Biology Department, Clark University, Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de São Paulo, 950 Main St., Rua Pedro Vicente 625, Worcester, MA 01610, USA São Paulo, SP 01109-010, Brazil e-mail: [email protected] O. -

<I>Melanoleuca</I>

ISSN (print) 0093-4666 © 2011. Mycotaxon, Ltd. ISSN (online) 2154-8889 MYCOTAXON Volume 115, pp. 215–226 January–March 2011 doi: 10.5248/115.215 Observations on Melanoleuca. Type studies – 3 Roberto Fontenla¹* & Roberto Para ² ¹ Via Monte Marino, 26 – I 60125 Ancona, Italy ² Via Martiri di via Fani, 22 – I 61024 Mombaroccio (PU), Italy Correspondence to *: [email protected] Abstract — The results of type studies on several taxa of the genusMelanoleuca are reported and discussed: Melanoleuca substrictipes, M. polioleuca, M. alutaceopallens, M. permixta, M. wrightii, M. lapataiae, and M. lapataiae var. ochroleuca. For the first two taxa a lectotype and a neotype are designated respectively. Key words — taxonomy, Tricholomatales Introduction Type materials of sixteen critical Melanoleuca taxa have already been discussed in two previous publications (Fontenla & Para 2007, 2008). Fontenla & Para (2007) reported on M. diverticulata G. Moreno & Bon, M. electropoda Maire & Malençon, M. kavinae (Pilát & Veselý) Singer, M. meridionalis G. Moreno & Barrasa, M. metrodii Bon, M. nigrescens (Bres.) Bon, and M. pseudobrevipes Bon. Fontenla & Para (2008) discussed Melanoleuca decembris Métrod ex Bon, Tricholoma humile var. bulbosum Peck, M. luteolosperma (Britzelm.) Singer, Clitocybe nobilis Peck, M. pseudopaedida Bon, M. decembris var. pseudorasilis Bon, M. subalpina (Britzelm.) Bresinsky & Stangl, M. subdura (Banning & Peck) Murrill, and M. tucumanensis Singer. In this paper we hope to shed new light on seven more taxonomically critical taxa and designate one lectotype and two neotypes to clarify relationships of the three taxa to their closest allies. Materials & methods Microscopical characters were examined using a Leitz Biomed optical microscope equipped with 100×, 500× and 1000× lenses; a stereomicroscope mod. -

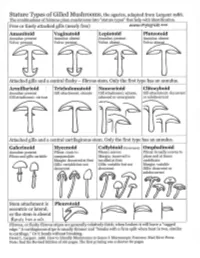

Agarics-Stature-Types.Pdf

Gilled Mushroom Genera of Chicago Region, by stature type and spore print color. Patrick Leacock – June 2016 Pale spores = white, buff, cream, pale green to Pinkish spores Brown spores = orange, Dark spores = dark olive, pale lilac, pale pink, yellow to pale = salmon, yellowish brown, rust purplish brown, orange pinkish brown brown, cinnamon, clay chocolate brown, Stature Type brown smoky, black Amanitoid Amanita [Agaricus] Vaginatoid Amanita Volvariella, [Agaricus, Coprinus+] Volvopluteus Lepiotoid Amanita, Lepiota+, Limacella Agaricus, Coprinus+ Pluteotoid [Amanita, Lepiota+] Limacella Pluteus, Bolbitius [Agaricus], Coprinus+ [Volvariella] Armillarioid [Amanita], Armillaria, Hygrophorus, Limacella, Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Coprinus+, Hypholoma, Neolentinus, Pleurotus, Tricholoma Cyclocybe, Gymnopilus Lacrymaria, Stropharia Hebeloma, Hemipholiota, Hemistropharia, Inocybe, Pholiota Tricholomatoid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Laccaria, Lactarius, Entoloma Cortinarius, Hebeloma, Lyophyllum, Megacollybia, Melanoleuca, Inocybe, Pholiota Russula, Tricholoma, Tricholomopsis Naucorioid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Hypsizygus, Laccaria, Entoloma Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Hypholoma Lactarius, Rhodocollybia, Rugosomyces, Hebeloma, Gymnopilus, Russula, Tricholoma Pholiota, Simocybe Clitocyboid Ampulloclitocybe, Armillaria, Cantharellus, Clitopilus Paxillus, [Pholiota], Clitocybe, Hygrophoropsis, Hygrophorus, Phylloporus, Tapinella Laccaria, Lactarius, Lactifluus, Lentinus, Leucopaxillus, Lyophyllum, Omphalotus, Panus, Russula Galerinoid Galerina, Pholiotina, Coprinus+, -

Justo Et Al 2010 Pluteaceae.Pdf

ARTICLE IN PRESS fungal biology xxx (2010) 1e20 journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/funbio Phylogeny of the Pluteaceae (Agaricales, Basidiomycota): taxonomy and character evolution Alfredo JUSTOa,*,1, Alfredo VIZZINIb,1, Andrew M. MINNISc, Nelson MENOLLI Jr.d,e, Marina CAPELARId, Olivia RODRıGUEZf, Ekaterina MALYSHEVAg, Marco CONTUh, Stefano GHIGNONEi, David S. HIBBETTa aBiology Department, Clark University, 950 Main St., Worcester, MA 01610, USA bDipartimento di Biologia Vegetale, Universita di Torino, Viale Mattioli 25, I-10125 Torino, Italy cSystematic Mycology & Microbiology Laboratory, USDA-ARS, B011A, 10300 Baltimore Ave., Beltsville, MD 20705, USA dNucleo de Pesquisa em Micologia, Instituto de Botanica,^ Caixa Postal 3005, Sao~ Paulo, SP 010631 970, Brazil eInstituto Federal de Educac¸ao,~ Ciencia^ e Tecnologia de Sao~ Paulo, Rua Pedro Vicente 625, Sao~ Paulo, SP 01109 010, Brazil fDepartamento de Botanica y Zoologıa, Universidad de Guadalajara, Apartado Postal 1-139, Zapopan, Jal. 45101, Mexico gKomarov Botanical Institute, 2 Popov St., St. Petersburg RUS-197376, Russia hVia Marmilla 12, I-07026 Olbia (OT), Italy iInstituto per la Protezione delle Piante, CNR Sezione di Torino, Viale Mattioli 25, I-10125 Torino, Italy article info abstract Article history: The phylogeny of the genera traditionally classified in the family Pluteaceae (Agaricales, Received 17 June 2010 Basidiomycota) was investigated using molecular data from nuclear ribosomal genes Received in revised form (nSSU, ITS, nLSU) and consequences for taxonomy and character evolution were evaluated. 16 September 2010 The genus Volvariella is polyphyletic, as most of its representatives fall outside the Pluteoid Accepted 26 September 2010 clade and shows affinities to some hygrophoroid genera (Camarophyllus, Cantharocybe). Corresponding Editor: Volvariella gloiocephala and allies are placed in a different clade, which represents the sister Joseph W. -

The Evolution of Secondary Metabolism Regulation and Pathways in the Aspergillus Genus

THE EVOLUTION OF SECONDARY METABOLISM REGULATION AND PATHWAYS IN THE ASPERGILLUS GENUS By Abigail Lind Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Biomedical Informatics August 11, 2017 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Antonis Rokas, Ph.D. Tony Capra, Ph.D. Patrick Abbot, Ph.D. Louise Rollins-Smith, Ph.D. Qi Liu, Ph.D. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people helped and encouraged me during my years working towards this dissertation. First, I want to thank my advisor, Antonis Rokas, for his support for the past five years. His consistent optimism encouraged me to overcome obstacles, and his scientific insight helped me place my work in a broader scientific context. My committee members, Patrick Abbot, Tony Capra, Louise Rollins-Smith, and Qi Liu have also provided support and encouragement. I have been lucky to work with great people in the Rokas lab who helped me develop ideas, suggested new approaches to problems, and provided constant support. In particular, I want to thank Jen Wisecaver for her mentorship, brilliant suggestions on how to visualize and present my work, and for always being available to talk about science. I also want to thank Xiaofan Zhou for always providing a new perspective on solving a problem. Much of my research at Vanderbilt was only possible with the help of great collaborators. I have had the privilege of working with many great labs, and I want to thank Ana Calvo, Nancy Keller, Gustavo Goldman, Fernando Rodrigues, and members of all of their labs for making the research in my dissertation possible. -

Taxonomy, Ecology and Distribution of Melanoleuca Strictipes (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) in Europe

CZECH MYCOLOGY 69(1): 15–30, MAY 9, 2017 (ONLINE VERSION, ISSN 1805-1421) Taxonomy, ecology and distribution of Melanoleuca strictipes (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) in Europe 1 2 3 4 ONDREJ ĎURIŠKA ,VLADIMÍR ANTONÍN ,ROBERTO PARA ,MICHAL TOMŠOVSKÝ , 5 SOŇA JANČOVIČOVÁ 1 Comenius University in Bratislava, Faculty of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmacognosy and Botany, Kalinčiakova 8, SK-832 32 Bratislava, Slovakia; [email protected] 2 Department of Botany, Moravian Museum, Zelný trh 6, CZ-659 37 Brno, Czech Republic; [email protected] 3 Via Martiri di via Fani 22, I-61024 Mombaroccio, Italy; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Forestry and Wood Technology, Mendel University in Brno, Zemědělská 3, CZ-613 00 Brno, Czech Republic; [email protected] 5 Comenius University in Bratislava, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Department of Botany, Révová 39, SK-811 02 Bratislava, Slovakia; [email protected] Ďuriška O., Antonín V., Para R., Tomšovský M., Jančovičová S. (2017): Taxonomy, ecology and distribution of Melanoleuca strictipes (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) in Europe. – Czech Mycol. 69(1): 15–30. Melanoleuca strictipes (P. Karst.) Métrod, a species characterised by whitish colours and macrocystidia in the hymenium, has for years been identified as several different species. Based on morphological studies of 61 specimens from eight countries and a phylogenetic analysis of ITS se- quences, including type material of M. subalpina and M. substrictipes var. sarcophyllum, we confirm conspecificity of these specimens and their identity as M. strictipes. The lectotype of this species is designated here. The morphological and ecological characteristics of this species are presented. Key words: taxonomy, phylogeny, M. -

Wood Chip Fungi: Agrocybe Putaminum in the San Francisco Bay Area

Wood Chip Fungi: Agrocybe putaminum in the San Francisco Bay Area Else C. Vellinga Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, 111 Koshland Hall, Berkeley CA 94720-3102 [email protected] Abstract Agrocybe putaminum was found growing on wood chips in central coastal California; this appears to be the first record for North America. A short description of the species is given. Its habitat plus the characteristics of wood chip denizens are discussed. Wood chips are the fast food of the fungal world. The desir- able wood is exposed, there is a lot of it, and often the supply is replenished regularly. It is an especially good habitat for mush- room species that like it hot because a thick layer of wood chips is warmed relative to the surrounding environment by the activity of bacteria and microscopic fungi (Brown, 2003; Van den Berg and Vellinga, 1998). Thirty years ago wood chips were a rarity, but nowadays they are widely used in landscaping and gardening. A good layer of chips prevents weeds from germinating and taking over, which means less maintenance and lower costs. Chips also diminish evaporation and keep moisture in the soil. Trees and shrubs are often shredded and dumped locally, but there is also long-dis- tance transport of these little tidbits. Barges full of wood mulch cruise the Mississippi River, and trucks carry the mulch from city to city. This fast food sustains a steady stream of wood chip fungi that, as soon as they are established, fruit in large flushes and are suddenly everywhere. The fungi behave a bit like morels after a Figure 1. -

MELANOLEUCA COGNATA (Fr.) Konrad & Maubl

MELANOLEUCA COGNATA (Fr.) Konrad & Maubl. SYNONYMES Tricholoma cognatum (Fr.) Gillet BIBLIOGRAPHIE Boekhout, 1988, Persoonia, 13-4 : 414 Boekhout, 1999, Flora Agaricina Neerlandica, 4 : 160 Bon, 1988, Champignons d’Europe occidentale : 164 Bon, 1991, Les Tricholomes et ressemblants : 132 Breitenbach & Kränzlin, 1995, Champignons de Suisse, 3 : 299 Courtecuisse & Duhem, 1994, Guide des champignons de France et d’Europe : 447 Konrad & Maublanc, Icones selectae Fungorum : Planche 271 Kühner, 1978, Bulletin de la Société Linnéenne de Lyon, 47 : 31 Kühner & Romagnesi, 1953, Flore analytique : 146 Lange, 1936, Flora Agaricina Danica, 1 (Réimp. 1993) : 46, 229 (sn. Tricholoma cognata) Marchand, 1973, Champignons du nord et du midi, 2 : 135 Moser, 1978, Kleine Kryptogamenflora (Traduction française) : 251 ICONOGRAPHIE Bon, 1988, Champignons d’Europe occidentale : 165 Breitenbach & Kränzlin, 1995, Champignons de Suisse, 3 : 299 Courtecuisse & Duhem, 1994, Guide des champignons de France et d’Europe : 447 Dähncke, 1993, 1200 Pilze : 308 Konrad & Maublanc, Icones selectae Fungorum : Planche 271 Lange, 1936, Flora Agaricina Danica, 1 (Réimp. 1993) : Tav. 30 A (sn. Tricholoma cognata) Marchand, 1973, Champignons du nord et du midi, 2 : 135 Roux, 2006, Mille et un champignons : 389 OBSERVATIONS Bon dans sa monographie de 1991, décrit Melanoleuca cognata dans un sens large, les nombreux caractères croisés constatés dans la plupart des récoltes interdisant de dégager des taxons différents en fonction des couleurs +/- vives, de la forme des cystides ou de l’écologie. Index fungorum, va même plus loin puisqu’il assimile au type, les variétés nauseosa, pallidipes et robusta. Classé dans la section des Cognatae, regroupant les espèces macrocystidiées de couleurs vives, Melanoleuca cognata est caract érisé par des carpophores presque entièrement concolores, café au lait à brun orangé ou ocracé vif, et par des macrocystides de forme variable, lagéniformes ou fusiformes, parfois difformes. -

MANUSCRIT Nina

AIX-MARSEILLE UNIVERSITE FACULTE DE MÉDECINE DE MARSEILLE ECOLE DOCTORALE DES SCIENCES DE LA VIE ET DE LA SANTE THÈSE DE DOCTORAT/PhD Présentée par Nina Gouba Le mycobiome digestif humain : étude exploratoire Soutenance le 09 décembre 2013 En vue de l’obtention du grade de DOCTEUR de l’UNIVERSITE d’AIX- MARSEILLE Spécialité : Pathologie Humaine Maladies Infectieuses Membres du jury de la Thèse : Président de jury : Professeur Jean Louis MEGE Rapporteur Professeur Bertrand PICARD Rapporteur Professeur Antoine ANDREMONT Directeur de thèse Professeur Michel DRANCOURT Unité de recherche sur les Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales Emergentes UM63, CNRS 7278, IRD 198, Inserm 1095, Faculté de Médecine, Marseille 1 AVANT PROPOS Le format de présentation de cette thèse correspond à une recommandation de la spécialité Maladies Infectieuses et Microbiologie, à l’intérieur du Master des Sciences de la Vie et de la Santé qui dépend de l’Ecole Doctorale des Sciences de la Vie de Marseille. Le candidat est amené à respecter des règles qui lui sont imposées et qui comportent un format de thèse utilisé dans le Nord de l’Europe et qui permet un meilleur rangement que les thèses traditionnelles. Par ailleurs, la partie introduction et bibliographie est remplacée par une revue envoyée dans un journal afin de permettre une évaluation extérieure de la qualité de la revue et de permettre à l’étudiant de commencer le plus tôt possible une bibliographie exhaustive sur le domaine de cette thèse. Par ailleurs, la thèse est présentée sur article publié, accepté ou soumis, associé d’un bref commentaire donnant le sens général du travail. -

Melanoleuca Dominicana Fungal Planet Description Sheets 365

364 Persoonia – Volume 45, 2020 Melanoleuca dominicana Fungal Planet description sheets 365 Fungal Planet 1161 – 19 December 2020 Melanoleuca dominicana Angelini, Para & Vizzini, sp. nov. Etymology. The name dominicana (Spanish) refers to the occurrence of Additional materials examined. DOMINICAN REPUBLIC, Puerto Plata, Sosua, the species in the Dominican Republic. one basidiome collected on litter of a heavily anthropized humid woodland of deciduous trees, a few km from the sea, 29 Nov. 2013, C. Angelini Classification — Incertae sedis in the Pluteineae, Agaricales, JBSD130781; ibid., 30 Nov. 2013, C. Angelini, JBSD130780, ITS sequence Agaricomycetes. GenBank MT991406. Pileus 4–5 cm diam, applanate, depressed with an umbili- Notes — The new species belongs in subg. Urticocystis. cate centre, rarely with a large and low umbo; pileus surface The two collections of Melanoleuca dominicana clustered in a smooth, opaque, always very dark in the centre, brownish, up strongly supported clade (MLB = 100) sister to M. jaliscoensis to blackish brown, otherwise ochre-brown, grey-brownish, also and M. longisterigma clade but without support. Melanoleuca ash-grey. Lamellae medium crowded, with numerous lamellulae dominicana is well differentiated from the other Melanoleuca (l = 1–3) of various lengths emarginated with long decurrent species described in literature, based on morphological and/or tooth, straight, white. Stipe 3.5–4 × 0.5–1 cm, central, cylin- molecular characteristics. Melanoleuca tucumanensis, M. tucu- drical, enlarged at the apex, clavate at the base, longitudinally manensis var. colorata and M. tucumanensis var. striata from fibrillose, from brown to dirty greyish brown, blackening at the Argentina (Singer & Digilio 1951, Raithelhuber 1974) have base. Context white brownish in the pileus, brown in the stipe, larger spores (7.5–10.3 × 6.2–7.5 µm, Singer & Digilio 1951; brown blackish in the stipe base. -

Lists of Names in Aspergillus and Teleomorphs As Proposed by Pitt and Taylor, Mycologia, 106: 1051-1062, 2014 (Doi: 10.3852/14-0

Lists of names in Aspergillus and teleomorphs as proposed by Pitt and Taylor, Mycologia, 106: 1051-1062, 2014 (doi: 10.3852/14-060), based on retypification of Aspergillus with A. niger as type species John I. Pitt and John W. Taylor, CSIRO Food and Nutrition, North Ryde, NSW 2113, Australia and Dept of Plant and Microbial Biology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3102, USA Preamble The lists below set out the nomenclature of Aspergillus and its teleomorphs as they would become on acceptance of a proposal published by Pitt and Taylor (2014) to change the type species of Aspergillus from A. glaucus to A. niger. The central points of the proposal by Pitt and Taylor (2014) are that retypification of Aspergillus on A. niger will make the classification of fungi with Aspergillus anamorphs: i) reflect the great phenotypic diversity in sexual morphology, physiology and ecology of the clades whose species have Aspergillus anamorphs; ii) respect the phylogenetic relationship of these clades to each other and to Penicillium; and iii) preserve the name Aspergillus for the clade that contains the greatest number of economically important species. Specifically, of the 11 teleomorph genera associated with Aspergillus anamorphs, the proposal of Pitt and Taylor (2014) maintains the three major teleomorph genera – Eurotium, Neosartorya and Emericella – together with Chaetosartorya, Hemicarpenteles, Sclerocleista and Warcupiella. Aspergillus is maintained for the important species used industrially and for manufacture of fermented foods, together with all species producing major mycotoxins. The teleomorph genera Fennellia, Petromyces, Neocarpenteles and Neopetromyces are synonymised with Aspergillus. The lists below are based on the List of “Names in Current Use” developed by Pitt and Samson (1993) and those listed in MycoBank (www.MycoBank.org), plus extensive scrutiny of papers publishing new species of Aspergillus and associated teleomorph genera as collected in Index of Fungi (1992-2104).