(Rakhine), 1942–43 by Jacques P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015 This document is published by the Center for Diversity and National Harmony with the support of the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund. Publisher : Center for Diversity and National Harmony No. 11, Shweli Street, Kamayut Township, Yangon. Offset : Public ation Date : September 2015 © All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Rakhine State, one of the poorest regions in Myanmar, has been plagued by communal problems since the turn of the 20th century which, coupled with protracted underdevelopment, have kept residents in a state of dire need. This regrettable situation was compounded from 2012 to 2014, when violent communal riots between members of the Muslim and Rakhine communities erupted in various parts of the state. Since the middle of 2012, the Myanmar government, international organisations and non-governmen- tal organisations (NGOs) have been involved in providing humanitarian assistance to internally dis- placed and conflict-affected persons, undertaking development projects and conflict prevention activ- ities. Despite these efforts, tensions between the two communities remain a source of great concern, and many in the international community continue to view the Rakhine issue as the biggest stumbling block in Myanmar’s reform process. The persistence of communal tensions signaled a need to address one of the root causes of conflict: crushing poverty. However, even as various stakeholders have attempted to restore normalcy in the state, they have done so without a comprehensive needs assessment to guide them. In an attempt to fill this gap, the Center for Diversity and National Harmony (CDNH) undertook the task of developing a source of baseline information on Rakhine State, which all stakeholders can draw on when providing humanitarian and development assistance as well as when working on conflict prevention in the state. -

Rohingya – the Name and Its Living Archive Jacques Leider

Rohingya – the Name and its Living Archive Jacques Leider To cite this version: Jacques Leider. Rohingya – the Name and its Living Archive. 2018. hal-02325206 HAL Id: hal-02325206 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02325206 Submitted on 25 Oct 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Spotlight: The Rakhine Issue Rohingya – the Name and its Living Archive Jacques P. Leider deconstructs the living history of the name “Rohingya.” he intriguingly opposing trends about using, not to do research on the history of the Rohingya and the name Tusing or rejecting the name “Rohingya” illustrate itself. Rohingyas and pro-Rohingya activists were keen to a captivating history of the naming and self-identifying prove that the Union of Burma had already recognised the of Arakan’s Muslim community. Today, “Rohingya” is Rohingya as an ethnic group in the 1950s and 1960s so that globally accepted as the name for most Muslims in North their citizenship rights could not be denied. Academics and Rakhine. But authorities and most people in Myanmar still independent researchers also formed archives containing use the term “Bengalis” in referring to the self-identifying official and non-official documents that allowed a close Rohingyas, linking them to Bangladesh and Burma’s own examination of the chronological record. -

Dr. Jacques P. Leider (Bangkok; Yangon) Muslimische Gemeinschaften Im Buddhistischen Myanmar Die Rohingyafrage. Vom Ethno-Kultur

Gastvorträge zu Religion und Politik in Myanmar / Südostasien Dr. Jacques P. Leider (Bangkok; Yangon) Montag, 25.Juni, 16-18 Uhr. Ort: Hüfferstrasse 27, 3.Obergeschoss, Raum B.3.06 Muslimische Gemeinschaften im buddhistischen Myanmar Der Vortrag bietet einen historischen Überblick über die Bildung muslimischer Gemeinschaften von der Zeit der buddhistischen Königreiche über die Kolonialzeit bis in die Zeit des unabhängigen Birmas (Myanmar). Das Wiedererstarken eines buddhistischen Nationalismus der birmanischen Bevölke-rungsmehrheit ist Hintergund islamophober Gewaltexzesse im Zuge der politischen Öffnung seit 2011. Der historische Rückblick versucht die Aktualität in die gesellschaftlichen Zusammenhänge und die zeitgenössiche Geschichte des Landes einzuordnen. Dienstag, 26.Juni, 10-12 Uhr. Ort: Johannisstr. 8-10, KTh V Die Rohingyafrage. Vom ethno-kulturellen Konflikt zum Vorwurf des staatlichen Genozids Die Rohingyas stellen die grösste muslimische Bevölkerungsgruppe in Myanmar. Die Hälfte der Muslime die die Rohingyaidentität in Anspruch nimmt, lebt aber, teils seit Jahrzehnten, ausserhalb des Landes. Ihre langjährige Unterdrückung, ihre politische Verfolgung und ihre massive Vertreibung haben die humanitären und legalen Aspekte der Rohingyafrage insbesondere seit Mitte 2017 ins Zen-trum des globalen Interesses an Myanmar gerückt. Der Vortrag wird insbesondere die widersprüch-lichen myanmarischen und internationalen Positionen zur Rohingyafrage besprechen. © Sai Lin Aung Htet Dr. Jacques P. Leider ist Historiker und Südostasienforscher der Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient und lebt in Bangkok und Yangon. Der Schwerpunkt seiner wissenschaftlichen Arbeit liegt im Bereich der frühmodernen und kolonialen Geschichte der Königreiche Arakans (Rakhine State) und Birmas (Myanmar). Im Rahmen des ethno-religiösen Konflikts in Rakhine State hat er sich verstärkt mit dem Hintergrund der Identitätsbildung der muslimischen Rohingya im Grenzgebiet zu Bangladesh beschäftigt. -

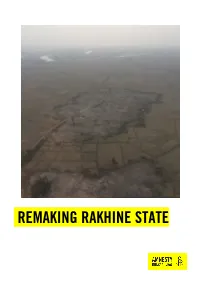

Remaking Rakhine State

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

Bulletin of the Burma Studies Group

Bulletin of the Burma Studies Group International Burma Studies Conference 2012 Northern Illinois University DeKalb, IL, USA October 5-7, 2012 Number 89 & 90 Spring/Fall 2012 Dear Readers, conversations beyond what After a longer has, up to now, been a fairly Bulletin of the than expected small group of people. If hiatus of interest grows enough, we Burma Studies several can reconsider the decision to Group months, we publish only once a year. have now Southeast Asian Council I hope readers will find this new completed the Association for Asian Studies format to be more attractive latest issue of and interesting, one which you the Bulletin of the Burma Studies all will want to contribute to. Spring/Fall 2012 Group. I have taken over duties Eliciting contributions has been from Ward Keeler. For those a long-standing problem for the of you who do not know me, I Contents Bulletin, so I thought it might have been involved in Burma be useful to talk a bit about Studies since I began studying who we are and what we look Introduction the Burmese language in 1995. Patrick McCormick Pg. 2 for in the Bulletin. From what I have been living in Rangoon I have been able to see as the since 2006 and got a PhD in new editor and formerly as a From My Election Diary, history in 2010, but I have also March-April 2012 reader of the Bulletin for several been working there since 2008. Hans-Bernd Zollner Pg. 4 years, it appears that readers After some discussion, we have are the “usual suspects”: Those “Rohingya”, Rakhaing and decided that we can no longer of us who attend and present at the Recent Outbreak of Violence - the Burma Studies conferences A Note justify bi-annual publication Jacques P. -

BURMA (MYANMAR) COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

BURMA (MYANMAR) COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service 17 June 2011 BURMA (MYANMAR) 17 JUNE 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN BURMA FROM 16 MAY TO 17 JUNE 2011 Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON BURMA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 16 MAY AND 17 JUNE 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Map ........................................................................................................................ 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY (INDEPENDENCE (1948) – NOVEMBER 2010) ................................................ 3.01 Constitutional referendum – 2008....................................................................... 3.03 Build up to 2010 elections ................................................................................... 3.05 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS (NOVEMBER 2010 – MARCH 2011)....................................... 4.01 November 2010 elections .................................................................................... 4.01 Release of Aung San Suu Kyi ............................................................................. 4.13 Opening of Parliament ......................................................................................... 4.16 5. CONSTITUTION......................................................................................................... -

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945- )

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945 - ) Major Events in the Life of a Revolutionary Leader All terms appearing in bold are included in the glossary. 1945 On June 19 in Rangoon (now called Yangon), the capital city of Burma (now called Myanmar), Aung San Suu Kyi was born the third child and only daughter to Aung San, national hero and leader of the Burma Independence Army (BIA) and the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL), and Daw Khin Kyi, a nurse at Rangoon General Hospital. Aung San Suu Kyi was born into a country with a complex history of colonial domination that began late in the nineteenth century. After a series of wars between Burma and Great Britain, Burma was conquered by the British and annexed to British India in 1885. At first, the Burmese were afforded few rights and given no political autonomy under the British, but by 1923 Burmese nationals were permitted to hold select government offices. In 1935, the British separated Burma from India, giving the country its own constitution, an elected assembly of Burmese nationals, and some measure of self-governance. In 1941, expansionist ambitions led the Japanese to invade Burma, where they defeated the British and overthrew their colonial administration. While at first the Japanese were welcomed as liberators, under their rule more oppressive policies were instituted than under the British, precipitating resistance from Burmese nationalist groups like the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL). In 1945, Allied forces drove the Japanese out of Burma and Britain resumed control over the country. 1947 Aung San negotiated the full independence of Burma from British control. -

Malteser MCH-PHC-WASH Activities in Maungdaw Township Rakhine State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Malteser MCH-PHC-WASH Activities in Maungdaw Township Rakhine State 92°10'E 92°20'E 92°30'E Chin Mandalay PALETWA BANGLADESH Ü Rakhine Magway Baw Tu Lar In Tu Lar Bago Tat Chaung Myo Naw Yar Hpar Zay Dar A®vung Tha Pyay San Su Ri Ayeyarwady Kar Lar Day Hpet N N ' ' 0 0 2 !< Myo (Ye Aung Chaung) 2 ° ° 1 Kyaung Toe Mar Zay 1 2 !< !< 2 Bwin (Baung)!< Aung Zan !< Gu Mi Yar Shee Dar !< Ye Aung San Ya Bway V# !< Kyaung Na Hpay (Myo) Kaung Na Phay Ah Nauk Tan Chaung Gaw Yan Ywa Tone Chaung !< !< #0 Ah Shey Htan Chaung (Htan Kar Li) Taing Bin Gar !< !< Ye Bauk Kyar Taung Pyo Sin Thay Pyin #0 !< #0 C! Ah Shey Kha Maung Seik Sin Shey Myo Kha Mg Seick (Nord) !< Mi Kyaung Chaung Ah Htet Bo Ka Lay Baw Taw Lar !< !< Ah San Kyaw !< Hlaing Thi !< Nga Yant Chaung Nan Yar Kaing (M) Auk Bo Ka Lay Min Zi Li !< !< Kyee Hnoke Thee V# Thit Tone Nar Gwa Son BANGLADESH #0 Let Yar Chaung Kyaung Zar Hpyu XY Ta Man Thar Ah Shey (Ku Lar) Pan Zi Ta Man Thar (Thet) Ta Man Thar (Ku Lar) Middle !< C! XY Ta Man Thar Thea Kone Tan C! Ta Man Thar Ah Nauk Rakhine Nga/Myin Baw Kha Mway Ta Man Thar TaunXYg Ta Man Thar Zay Nar/ Tan Tta MXYan Thar (Bo Hmu Gyi Thet) Yae Nauk Ngar Thar (Daing Nat) C! Nga/Myin Baw Ku Lar Taungpyoletwea XY Yae Nauk Ngar Thar (!v® Hpaung Seik Taung Pyo Let Yar Mee Taik Ba Da Kar That Kaing Nyar (Thet) BUTHIDAUNG Tha Ra Zaing !< Ah Yaing Kwet Chay C! !<Laung Boke Long Boat Hpon Thi #0 Aung Zay Ya (Nyein Chan Yay) Thin Baw Hla (Ku Lar) That Chaung Pu Zun Chaung !< Gara Pyin Ye Aung Chaung Thin Baw Hla (Rakhine) (Thar -

General Assembly Distr.: General 5 August 2020

United Nations A/75/288 General Assembly Distr.: General 5 August 2020 Original: English Seventy-fifth session Item 72 (c) of the provisional agenda* Promotion and protection of human rights: human rights situations and reports of special rapporteurs and representatives Report on the implementation of the recommendations of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar Note by the Secretary-General The Secretary-General has the honour to transmit to the General Assembly the report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the implementation of the recommendations of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar and on progress in the situation of human rights in Myanmar, pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 42/3. * A/75/150. 20-10469 (E) 240820 *2010469* A/75/288 Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the situation of human rights in Myanmar Summary The independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar issued two reports and four thematic papers. For the present report, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights analysed 109 recommendations, grouped thematically on conflict and the protection of civilians; accountability; sexual and gender-based violence; fundamental freedoms; economic, social and cultural rights; institutional and legal reforms; and action by the United Nations system. 2/17 20-10469 A/75/288 I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 42/3, in which the Council requested the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to follow up on the implementation by the Government of Myanmar of the recommendations made by the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar, including those on accountability, and to continue to track progress in relation to human rights, including those of Rohingya Muslims and other minorities, in the country. -

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider To cite this version: Jacques Leider. The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations. Morten Bergsmo; Wolfgang Kaleck; Kyaw Yin Hlaing. Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, 40, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, pp.177-227, 2020, Publication Series, 978-82-8348-134-1. hal- 02997366 HAL Id: hal-02997366 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02997366 Submitted on 10 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors) E-Offprint: Jacques P. Leider, “The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations”, in Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors), Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPub- lisher, Brussels, 2020 (ISBNs: 978-82-8348-133-4 (print) and 978-82-8348-134-1 (e- book)). This publication was first published on 9 November 2020. TOAEP publications may be openly accessed and downloaded through the web site https://www.toaep.org which uses Persistent URLs (PURLs) for all publications it makes available. -

Quarterly Performance Report from October 01, 2017 to December 31, 2017

DEFEAT MALARIA Defeat Malaria Quarterly Performance Report From October 01, 2017 to December 31, 2017 Submission Date: January 31, 2018 Agreement Number: AID-482-A-16-00003 Agreement Period: August 15, 2016 to August 14, 2021 AOR Name: Dr. Monti Feliciano Submitted by: May Aung Lin, Chief of Party University of Research Co., LLC. Room 602, 6th Floor, Shwe Than Lwin Condominium New University Ave. Rd., Bahan Township Yangon, Myanmar Email: [email protected] This document was produced by University Research Co., LLC (URC) for review and approval by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Table of Contents List of Tables ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ii List of Figures ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- iii ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS --------------------------------------------------------------------------------- iv Executive Summary --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Defeat Malaria Goal and Objectives ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 7 Summary of Key Achievements (October – December 2017) ---------------------------------------------------- 9 Interventions and Achievements on Core Areas of Strategic Focus --------------------------------------------- 11 1. Achieving and sustaining scale of proven interventions through community and -

Migration from Bengal to Arakan During British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin

Occasional Paper Series Migration from Bengal to Arakan during British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin Migration from Bengal to Arakan during British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin 2019 Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher Brussels This and other publications in TOAEP’s Occasional Paper Series may be openly accessed and downloaded through the web site http://toaep.org, which uses Persistent URLs for all publications it makes available (such PURLs will not be changed). This publication was first published on 6 December 2019. © Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, 2019 All rights are reserved. You may read, print or download this publication or any part of it from http://www.toaep.org/ for personal use, but you may not in any way charge for its use by others, directly or by reproducing it, storing it in a retrieval system, transmitting it, or utilising it in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, in whole or in part, without the prior permis- sion in writing of the copyright holder. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the copyright holder. You must not circulate this publication in any other cover and you must impose the same condition on any ac- quirer. You must not make this publication or any part of it available on the Internet by any other URL than that on http://www.toaep.org/, without permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-82-8348-150-1. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 2 2. Setting the Scene: The 1911, 1921 and 1931 Censuses of British Burma ............................