Utah Symphony and Utah Opera: a Merger Proposal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BEYOND BOSTON Harborfest May Be the Main Show, but It’S Not the Only 4Th of July Party Around

what to do # where to go # what to see July 2–15, 2007 The Officficialial GuGuideide to BOSBOSTONTON Mr.Fourth of July Keith Lockhart and the Boston Pops Celebrate the U.S.A. PLUS: Boston with a French Accent New England Sand CHECK Sculpting Festival OUT OUR The Boston Lobsters NEW MAPS! Court Tennis Fans AFTER PAGE 80 www.panoramamagazine.com Come to Product availability may vary by store 2000707CELEbearATING 10 YEARS OF HUGS Visit us at Faneuil Hall Marketplace Over 300 stores worldwide! æ www.buildabear.com æ (toll free) 1-877-789-BEAR (2327) Coupon expires August 31, 2007. Coupons may not be combined and cannot be bought, sold or exchanged for cash or coupons. Not valid on prior purchases, a Build-A-Party® celebration, Bear Buck$® card, in Eat With Your Bear Hands Cafe, in Build-A-Bear Workshop® within Rainforest Cafe® or in Build-A-Dino® within T-REX CafeTM. Not valid with any other offer. Local and state taxes, as applicable, are payable by bearer. Must present original coupon at time of purchase or enter 5-digit code on web purchase. Photocopies prohibited. Valid in the U.S. only. Valid for coupon recipient only. Limit one coupon per person, per visit. Nontransferable. Offer good while supplies last. Void where Key #91388 prohibited or restricted. Where required cash value 1/100 of 1 cent. contents COVER STORY FEATURE STORY 22 Go Fourth! 24 Vive la France Panorama spotlights in Boston! Harborfest, the Hub’s How to celebrate Bastille Day official July 4th and French culture around town celebration DEPARTMENTS 8 around the hub 8 NEWS & NOTES 18 STYLE 14 DINING 20 NIGHTLIFE 16 ON STAGE 28 the hub directory 29 CURRENT EVENTS 35 MUSEUMS & GALLERIES 39 CLUBS & BARS 41 SIGHTSEEING 46 MAPS 53 EXCURSIONS 56 FREEDOM TRAIL 58 SHOPPING 64 RESTAURANTS 80 NEIGHBORHOODS 94 5 questions with… Conductor KEITH LOCKHART on the cover: Keith Lockhart relaxes at Symphony Hall before getting ready to lead the Boston Pops in its annual July 4 concert at the Hatch Shell on the Esplanade. -

Chuaqui C.V. 2019

MIGUEL CHUAQUI, Ph.D. Professor Director, University of Utah School of Music 1375 East Presidents Circle Salt Lake City, UT 84112 801-585-6975 [email protected] www.miguelchuaqui.com EDUCATION AND TRAINING 2007: Summer workshops in advanced Max/MSP programming, IRCAM, Paris. 1994 - 96: Post-doctoral studies in interactive electro-acoustic music, Center for New Music and Audio Technologies (CNMAT), University of California, Berkeley. 1994: Ph.D. in Music, University of California, Berkeley, Andrew Imbrie, graduate advisor. 1989: M.A. in Music, University of California, Berkeley. 1987: B.A. in Mathematics and Music, With Distinction, University of California, Berkeley. 1983: Studies in piano performance and Mathematics, Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile. 1982: Certificate in Spanish/English translation, Cambridge University, England. 1976 - 1983: Studies in piano performance, music theory and musicianship, Escuela Moderna de Música, Santiago, Chile. WORK HISTORY 2009 – present: Professor, School of Music, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah; Chair, Composition Area, 2008-2014. 2003 - 2009: Associate Professor, School of Music, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah. 1996 - 2003: Assistant Professor, School of Music, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah. 1994 – 1996: Organist and Assistant Conductor, St. Bonaventure Catholic Church, Clayton, California. 1992 - 1996: Instructor, Music Department, Laney College, Oakland, California. Music Theory and Musicianship. 1992 – 1993: Lecturer, Music Department, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, California. (One-year music theory sabbatical replacement position). 1989 – 1992: Graduate Student Instructor, University of California, Berkeley, California. updated 2/19 Miguel Chuaqui 2 UNIVERSITY, PROFESSIONAL, AND PUBLIC SERVICE ADMINISTRATIVE APPOINTMENTS 2015-present: Director, University of Utah School of Music. -

Shostakovich (1906-1975)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Born in St. Petersburg. He entered the Petrograd Conservatory at age 13 and studied piano with Leonid Nikolayev and composition with Maximilian Steinberg. His graduation piece, the Symphony No. 1, gave him immediate fame and from there he went on to become the greatest composer during the Soviet Era of Russian history despite serious problems with the political and cultural authorities. He also concertized as a pianist and taught at the Moscow Conservatory. He was a prolific composer whose compositions covered almost all genres from operas, ballets and film scores to works for solo instruments and voice. Symphony No. 1 in F minor, Op. 10 (1923-5) Yuri Ahronovich/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Overture on Russian and Kirghiz Folk Themes) MELODIYA SM 02581-2/MELODIYA ANGEL SR-40192 (1972) (LP) Karel Ancerl/Czech Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Symphony No. 5) SUPRAPHON ANCERL EDITION SU 36992 (2005) (original LP release: SUPRAPHON SUAST 50576) (1964) Vladimir Ashkenazy/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15, Festive Overture, October, The Song of the Forest, 5 Fragments, Funeral-Triumphal Prelude, Novorossiisk Chimes: Excerpts and Chamber Symphony, Op. 110a) DECCA 4758748-2 (12 CDs) (2007) (original CD release: DECCA 425609-2) (1990) Rudolf Barshai/Cologne West German Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1994) ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 6324 (11 CDs) (2003) Rudolf Barshai/Vancouver Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphony No. -

BIOGRAPHIES Violin Faculty Justin Chou Is a Performer, Teacher And

MASTER PLAYERS FESTIVAL: BIOGRAPHIES Violin faculty Justin Chou is a performer, teacher and concert producer. He has assisted and performed in productions such as the Master Players Concert Series, IVSO 60th anniversary, Asian Invasion recital series combining classical music and comedy, the 2012 TEDxUD event that streamed live across the Internet and personal projects like Violins4ward, which recently produced a concert titled “No Violence, Just Violins” to promote violence awareness and harmonious productivity. Chou’s current project, Verdant, is a spring classical series based in Wilmington, Delaware, that presents innovative concerts by growing music into daily life, combining classical performance with unlikely life passions. As an orchestral musician, he spent three years as concertmaster of the Illinois Valley Symphony, with duties that included solo performances with the orchestra. Chou also has performed in various orchestras in principal positions, including an international tour to Colombia with the University of Delaware Symphony Orchestra, and in the state of Wisconsin, with the University of Wisconsin Symphony Orchestra, the Lake Geneva Symphony Orchestra and the Beloit-Janesville Symphony. Chou received his master of music degree from UD under Prof. Xiang Gao, with a full assistantship, and his undergraduate degree from the University of Wisconsin, with Profs. Felicia Moye and Vartan Manoogian, where he received the esteemed Ivan Galamian Award. Chou also has received honorable mention in competitions like the Milwaukee Young Artist and Youth Symphony Orchestras competitions. Xiang Gao, MPF founding artistic director Recognized as one of the world's most successful performing artists of his generation from the People's Republic of China, Xiang Gao has solo performed for many world leaders and with more than 100 orchestras worldwide. -

Pianistta Tbilisis Meeqvse Saertasoriso Konkursi

pianistTa Tbilisis meeqvse saerTaSoriso konkursi 1-11 oqtomberi, 2017 damfuZnebeli: saqarTvelos musikaluri konkursebis fondi damfuZnebeli da samxatvro xelmZRvaneli manana doijaSvili THE SIXTH TBILISI INTERNATIONAL PIANO COMPETITION OCTOBER 1-11, 2017 Founded by THE GEORGIAN MUSIC COMPETITIONS FUND Founder & Artistic Director MANANA DOIJASHVILI The Georgian Music Competitions Fund V. Sarajishvili Tbilisi State Conservatoire Grand Hall Directorate of the Sixth Tbilisi International Piano Competition 8 Griboedov St. Tbilisi 0108 Georgia Tel: (+995 32) 292-24-46 Tel/fax: (+995 32) 292-24-47 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.tbilisipiano.org.ge 1 konkursis Catarebis pirobebi 1. pianistTa Tbilisis meeqvse saerTaSoriso konkursi Catardeba TbilisSi 2017 wlis 1-11 oqtombers. 2. konkursi tardeba 4 weliwadSi erTxel. 3. konkursSi monawileobis miReba SeuZlia yvela erovnebis musikoss, romelic dabadebulia 11984984 wwlislis 1111 ooqtombridanqtombridan 22001001 wwlislis 1 ooqtombramde.qtombramde. 4. konkursi tardeba oTx turad: I, II, III (naxevarfinali), IV (finali). naxevarfinalSi daiSveba 12 monawile, finalSi ki - 6. 5. yvela mosmena sajaroa. 6. programebi sruldeba zepirad. 7. turebSi nawarmoebebis gameoreba ar SeiZleba. 8. warmodgenil programebSi cvlilebebi dauSvebelia. 9. monawileTa gamosvlis Tanmimdevrobas gadawyvets kenWisyra. es Tanmimdevroba SenarCunebuli iqneba konkursis bolomde. 10. yoveli monawile valdebulia daeswros kenWisyras, romelic Catardeba 22017017 wwlislis 1 ooqtombers.qtombers. 11. naxevarfinalis monawileebs gadaecemaT sertifikatebi. -

Program Book

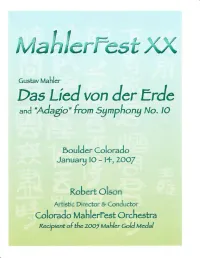

I e lson rti ic ire r & ndu r Schedule of Events CHAMBER CONCERTS Wednesday, January 1.O, 2007, 7100 PM Boulder Public Library Canyon Theater,9th & Canyon Friday, January L3, 7 3O PM Rocky Mountain Center for Musical Arts, 200 E. Baseline Rd., Lafayette Program: Songs on Chinese andJapanese Poems SYMPOSIUM Saturday, January L7, 2OO7 ATLAS Room 100, University of Colorado-Boulder 9:00 AM - 4:30 PM 9:00 AM: Robert Olson, MahlerFest Conductor & Artistic Director 10:00 AM: Evelyn Nikkels, Dutch Mahler Society 11:00 AMrJason Starr, Filmmaker, New York City Lunch 1:00 PM: Stephen E Heffiing, Case Western Reserve University, Keynote Speaker 2100 PM: Marilyn McCoy, Newburyport, MS 3:00 PMr Steven Bruns, University of Colorado-Boulder 4:00 PM: Chris Mohr, Denver, Colorado SYMPHONY CONCERTS Saturday, January L3' 2007 Sunday,Janaary L4,2O07 Macky Auditorium, CU Campus, Boulder Thomas Hampson, baritone Jon Garrison, tenor The Colorado MahlerFest Orchestra, Robert Olson, conductor See page 2 for details. Fundingfor MablerFest XXbas been Ttrouid'ed in ltartby grantsftom: The Boulder Arts Commission, an agency of the Boulder City Council The Scienrific and Culrural Facilities Discrict, Tier III, administered by the Boulder County Commissioners The Dietrich Foundation of Philadelphia The Boulder Library Foundation rh e va n u n dati o n "# I:I,:r# and many music lovers from the Boulder area and also from many states and countries [)AII-..]' CAMEI{\ il M ULIEN The ACADEMY Twent! Years and Still Going Strong It is almost impossible to fully comprehend -

To See the 2018 Tanglewood Schedule

summer 2018 BERNSTEIN CENTENNIAL SUMMER TANGLEWOOD.ORG 1 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ANDRIS NELSONS MUSIC DIRECTOR “That place [Tanglewood] is very dear to my heart, that is where I grew up and learned so much...in 1940 when I first played and studied there.” —Leonard Bernstein (November 1989) SEASONHIGHLIGHTS Throughoutthesummerof2018,Tanglewoodcelebratesthecentennialof AlsoleadingBSOconcertswillbeBSOArtisticPartnerThomas Adès(7/22), Lawrence-born,Boston-bredconductor-composerLeonardBernstein’sbirth. BSOAssistantConductorMoritz Gnann(7/13),andguestconductorsHerbert Bernstein’scloserelationshipwiththeBostonSymphonyOrchestraspanned Blomstedt(7/20&21),Charles Dutoit(8/3&8/5),Christoph Eschenbach ahalf-century,fromthetimehebecameaprotégéoflegendaryBSO (8/26),Juanjo Mena(7/27&29),David Newman(7/28),Michael Tilson conductorSergeKoussevitzkyasamemberofthefirstTanglewoodMusic Thomas(8/12),andBramwell Tovey(8/4).SoloistswiththeBSOalsoinclude Centerclassin1940untilthefinalconcertsheeverconducted,withtheBSO pianistsEmanuel Ax(7/20),2018KoussevitzkyArtistKirill Gerstein(8/3),Igor andTanglewoodMusicCenterOrchestraatTanglewoodin1990.Besides Levit(8/12),Paul Lewis(7/13),andGarrick Ohlsson(7/27);BSOprincipalflute concertworksincludinghisChichester Psalms(7/15), alilforfluteand Elizabeth Rowe(7/21);andviolinistsJoshua Bell(8/5),Gil Shaham(7/29),and orchestra(7/21),Songfest(8/4),theSerenade (after Plato’s “Symposium”) Christian Tetzlaff(7/22). (8/18),andtheBSO-commissionedDivertimentoforOrchestra(also8/18), ThomasAdèswillalsodirectTanglewood’s2018FestivalofContemporary -

Conducting Studies Conference 2016

Conducting Studies Conference 2016 24th – 26th June St Anne’s College University of Oxford Conducting Studies Conference 2016 24-26 June, St Anne’s College WELCOME It is with great pleasure that we welcome you to St Anne’s College and the Oxford Conducting Institute Conducting Studies Conference 2016. The conference brings together 44 speakers from around the globe presenting on a wide range of topics demonstrating the rich and multifaceted realm of conducting studies. The practice of conducting has significant impact on music-making across a wide variety of ensembles and musical contexts. While professional organizations and educational institutions have worked to develop the field through conducting masterclasses and conferences focused on professional development, and academic researchers have sought to explicate various aspects of conducting through focussed studies, there has yet to be a space where this knowledge has been brought together and explored as a cohesive topic. The OCI Conducting Studies Conference aims to redress this by bringing together practitioners and researchers into productive dialogue, promoting practice as research and raising awareness of the state of research in the field of conducting studies. We hope that this conference will provide a fruitful exchange of ideas and serve as a lightning rod for the further development of conducting studies research. The OCI Conducting Studies Conference Committee, Cayenna Ponchione-Bailey Dr John Traill Dr Benjamin Loeb Dr Anthony Gritten University of Oxford University of -

Ambassador Auditorium Collection ARS.0043

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3q2nf194 No online items Guide to the Ambassador Auditorium Collection ARS.0043 Finding aid prepared by Frank Ferko and Anna Hunt Graves This collection has been processed under the auspices of the Council on Library and Information Resources with generous financial support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Archive of Recorded Sound Braun Music Center 541 Lasuen Mall Stanford University Stanford, California, 94305-3076 650-723-9312 [email protected] 2011 Guide to the Ambassador Auditorium ARS.0043 1 Collection ARS.0043 Title: Ambassador Auditorium Collection Identifier/Call Number: ARS.0043 Repository: Archive of Recorded Sound, Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California 94305-3076 Physical Description: 636containers of various sizes with multiple types of print materials, photographic materials, audio and video materials, realia, posters and original art work (682.05 linear feet). Date (inclusive): 1974-1995 Abstract: The Ambassador Auditorium Collection contains the files of the various organizational departments of the Ambassador Auditorium as well as audio and video recordings. The materials cover the entire time period of April 1974 through May 1995 when the Ambassador Auditorium was fully operational as an internationally recognized concert venue. The materials in this collection cover all aspects of concert production and presentation, including documentation of the concert artists and repertoire as well as many business documents, advertising, promotion and marketing files, correspondence, inter-office memos and negotiations with booking agents. The materials are widely varied and include concert program booklets, audio and video recordings, concert season planning materials, artist publicity materials, individual event files, posters, photographs, scrapbooks and original artwork used for publicity. -

Salt Lake City August 1—4, 2019 Nfac Discover 18 Ad OL.Pdf 1 6/13/19 8:29 PM

47th Annual National Flute Association Convention Salt Lake City August 1 —4, 2019 NFAc_Discover_18_Ad_OL.pdf 1 6/13/19 8:29 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Custom Handmade Since 1888 Booth 110 wmshaynes.com Dr. Rachel Haug Root Katie Lowry Bianca Najera An expert for every f lutist. Three amazing utists, all passionate about helping you und your best sound. The Schmitt Music Flute Gallery offers expert consultations, easy trials, and free shipping to utists of all abilities, all around the world! Visit us at NFA booth #126! Meet our specialists, get on-site ute repairs, enter to win prizes, and more. schmittmusic.com/f lutegallery Wiseman Flute Cases Compact. Strong. Comfortable. Stylish. And Guaranteed for life. All Wiseman cases are hand- crafted in England from the Visit us at finest materials. booth 214 in All instrument combinations the exhibit hall, supplied – choose from a range of lining colours. Now also NFA 2019, Salt available in Carbon Fibre. Lake City! Dr. Rachel Haug Root Katie Lowry Bianca Najera An expert for every f lutist. Three amazing utists, all passionate about helping you und your best sound. The Schmitt Music Flute Gallery offers expert consultations, easy trials, and free shipping to utists of all abilities, all around the world! Visit us at NFA booth #126! Meet our specialists, get on-site ute repairs, enter to win prizes, and more. 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 [email protected] schmittmusic.com/f lutegallery www.wisemanlondon.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Committees ............................................................... -

Utah Symphony | Utah Opera

Media Contact: Renée Huang | Public Relations Director [email protected] | (801) 869-9027 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: UTAH SYMPHONY PRESENTS BERLIOZ’S DAMNATION OF FAUST WITH ACCLAIMED GUEST OPERA SOLOISTS KATE LINDSEY AND MICHAEL SPYRES SALT LAKE CITY, Utah (Sept.12, 2013) – Mezzo Soprano Kate Lindsey, a veteran of the Metropolitan Opera, and Michael Spyres, called “one of today’s finest tenors” by French Opera magazine join the Utah Symphony on September 27 and 28 at Abravanel Hall in Hector Berlioz’s dramatic interpretation of Goethe’s tale of Faust and his fateful deal with the devil, The Damnation of Faust. The Utah Symphony Chorus and Utah Opera Chorus lend their voices to the work, which is an ingenious combination of opera and oratorio that ranks among Berlioz’s finest creations. In addition to the star power of Lindsey and Spyres who sings the role of Marguerite and Faust, three other operatic guest artists will join the cast, including Baritone Roderick Williams, whose talents have included appearances with all BBC orchestras, London Sinfonietta and the Philharmonia, performing Mephistopheles; and Bass- baritone Adam Cioffari, a former member of the Houston Grand Opera Studio. Newcomer Tara Stafford Spyres, a young coloratura soprano, just sang her first Mimi in Springfield Missouri’s Regional Opera production of La Bohème. La Damnation de Faust was last performed on the Utah Symphony Masterworks Series in 2003 as part of the company’s Faust Festival. TICKET INFORMATION Single tickets for the performance range from $18 to $69 and can be purchased by phone at (801) 355- 2787, in person at the Abravanel Hall ticket office (123 W. -

National Conference Performing Choirs

National Conference Performing Choirs 20152015 ACDA FestivalFestival ChoirChoir UniversityUniversity ofof Utah A Cappella Choir Thursday 8:00 pm - 9:45 pm Abravanel Hall (Blue Track) Friday 8:00 pm - 9:45 pm Abravanel Hall (Gold Track) The 2015 ACDA Festival Choir includes the Utah Sym- phony Chorus, Utah Chamber Artists, the University of Utah Chamber Choir, and the University of Utah A Cappella Choir conducted by Barlow Bradford. The Utah Symphony is con- ducted by Thierry Fischer. Founded in 1962, the A Cappella Choir offers singers the opportunity to perform works for larger choirs and to fi ne- tune the art of choral singing through exposure to music from Utah Chamber Artists the Renaissance through the twenty-fi rst century. Choir mem- bers hone musicianship skills such as rhythm, sight-reading, and the understanding of complex scores. They develop an understanding of the intricacies of vocal production, includ- ing pitch, and how to blend individual voices together into a unifi ed, beautiful sound. In recent years, the A Cappella Choir has become a standard of excellence in student singing in the State of Utah. Last fall, they sang Mozart’s Trinity Mass with the Utah Symphony and the Utah Symphony Chorus under the direction of Thierry Fischer. This renewed a tradition of collaboration between the choirs of the University of Utah and the Utah Symphony, and their outstanding performance resulted in invitations for return engagements in 2015. Utah Chamber Artists was established in 1991 by Barlow University of Utah Chamber Choir Bradford and James Lee Sorenson. The ensemble comprises forty singers and forty players who create a balance and so- nority rarely found in a combined choir and orchestra.