MAHLER SYMPHONY No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chuaqui C.V. 2019

MIGUEL CHUAQUI, Ph.D. Professor Director, University of Utah School of Music 1375 East Presidents Circle Salt Lake City, UT 84112 801-585-6975 [email protected] www.miguelchuaqui.com EDUCATION AND TRAINING 2007: Summer workshops in advanced Max/MSP programming, IRCAM, Paris. 1994 - 96: Post-doctoral studies in interactive electro-acoustic music, Center for New Music and Audio Technologies (CNMAT), University of California, Berkeley. 1994: Ph.D. in Music, University of California, Berkeley, Andrew Imbrie, graduate advisor. 1989: M.A. in Music, University of California, Berkeley. 1987: B.A. in Mathematics and Music, With Distinction, University of California, Berkeley. 1983: Studies in piano performance and Mathematics, Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile. 1982: Certificate in Spanish/English translation, Cambridge University, England. 1976 - 1983: Studies in piano performance, music theory and musicianship, Escuela Moderna de Música, Santiago, Chile. WORK HISTORY 2009 – present: Professor, School of Music, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah; Chair, Composition Area, 2008-2014. 2003 - 2009: Associate Professor, School of Music, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah. 1996 - 2003: Assistant Professor, School of Music, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah. 1994 – 1996: Organist and Assistant Conductor, St. Bonaventure Catholic Church, Clayton, California. 1992 - 1996: Instructor, Music Department, Laney College, Oakland, California. Music Theory and Musicianship. 1992 – 1993: Lecturer, Music Department, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, California. (One-year music theory sabbatical replacement position). 1989 – 1992: Graduate Student Instructor, University of California, Berkeley, California. updated 2/19 Miguel Chuaqui 2 UNIVERSITY, PROFESSIONAL, AND PUBLIC SERVICE ADMINISTRATIVE APPOINTMENTS 2015-present: Director, University of Utah School of Music. -

Programme Information

Programme information Saturday 18th April to Friday 24th April 2020 WEEK 17 THE FULL WORKS CONCERT: CELEBRATING HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN’S BIRTHDAY Tuesday 21st April, 8pm to 10pm Jane Jones honours a very special birthday, as Queen Elizabeth II turns 94 years old. We hear from several different Masters of the Queen’s (or King’s) Music, from William Boyce who presided during the reign of King George II, to Judith Weir who was appointed the very first female Master of the Queen’s Music in 2014. The Central Band of the Royal Air Force also plays Nigel Hess’ Lochnagar Suite, inspired by Prince Charles’ book The Old Man of Lochnagar. Her Majesty has also supported classical music throughout her inauguration of The Queen’s Music Medal which is presented annually to an “outstanding individual or group of musicians who have had a major influence on the musical life of the nation”. Tonight, we hear from the 2016 recipient, Nicola Benedetti, who plays Vaughan Williams’ The Lark Ascending. Classic FM is available across the UK on 100-102 FM, DAB digital radio and TV, at ClassicFM.com, and on the Classic FM and Global Player apps. 1 WEEK 17 SATURDAY 18TH APRIL 3pm to 5pm: MOIRA STUART’S HALL OF FAME CONCERT Over Easter weekend, the new Classic FM Hall of Fame was revealed and this afternoon, Moira Stuart begins her first Hall of Fame Concert since the countdown with the snowy mountains in Sibelius’ Finlandia, which fell to its lowest ever position this year, before a whimsically spooky dance by Saint-Saens. -

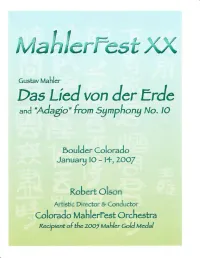

Program Book

I e lson rti ic ire r & ndu r Schedule of Events CHAMBER CONCERTS Wednesday, January 1.O, 2007, 7100 PM Boulder Public Library Canyon Theater,9th & Canyon Friday, January L3, 7 3O PM Rocky Mountain Center for Musical Arts, 200 E. Baseline Rd., Lafayette Program: Songs on Chinese andJapanese Poems SYMPOSIUM Saturday, January L7, 2OO7 ATLAS Room 100, University of Colorado-Boulder 9:00 AM - 4:30 PM 9:00 AM: Robert Olson, MahlerFest Conductor & Artistic Director 10:00 AM: Evelyn Nikkels, Dutch Mahler Society 11:00 AMrJason Starr, Filmmaker, New York City Lunch 1:00 PM: Stephen E Heffiing, Case Western Reserve University, Keynote Speaker 2100 PM: Marilyn McCoy, Newburyport, MS 3:00 PMr Steven Bruns, University of Colorado-Boulder 4:00 PM: Chris Mohr, Denver, Colorado SYMPHONY CONCERTS Saturday, January L3' 2007 Sunday,Janaary L4,2O07 Macky Auditorium, CU Campus, Boulder Thomas Hampson, baritone Jon Garrison, tenor The Colorado MahlerFest Orchestra, Robert Olson, conductor See page 2 for details. Fundingfor MablerFest XXbas been Ttrouid'ed in ltartby grantsftom: The Boulder Arts Commission, an agency of the Boulder City Council The Scienrific and Culrural Facilities Discrict, Tier III, administered by the Boulder County Commissioners The Dietrich Foundation of Philadelphia The Boulder Library Foundation rh e va n u n dati o n "# I:I,:r# and many music lovers from the Boulder area and also from many states and countries [)AII-..]' CAMEI{\ il M ULIEN The ACADEMY Twent! Years and Still Going Strong It is almost impossible to fully comprehend -

FRENCH SYMPHONIES from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

FRENCH SYMPHONIES From the Nineteenth Century To The Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman NICOLAS BACRI (b. 1961) Born in Paris. He began piano lessons at the age of seven and continued with the study of harmony, counterpoint, analysis and composition as a teenager with Françoise Gangloff-Levéchin, Christian Manen and Louis Saguer. He then entered the Paris Conservatory where he studied with a number of composers including Claude Ballif, Marius Constant, Serge Nigg, and Michel Philippot. He attended the French Academy in Rome and after returning to Paris, he worked as head of chamber music for Radio France. He has since concentrated on composing. He has composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. His unrecorded Symphonies are: Nos. 1, Op. 11 (1983-4), 2, Op. 22 (1986-8), 3, Op. 33 "Sinfonia da Requiem" (1988-94) and 5 , Op. 55 "Concerto for Orchestra" (1996-7).There is also a Sinfonietta for String Orchestra, Op. 72 (2001) and a Sinfonia Concertante for Orchestra, Op. 83a (1995-96/rév.2006) . Symphony No. 4, Op. 49 "Symphonie Classique - Sturm und Drang" (1995-6) Jean-Jacques Kantorow/Tapiola Sinfonietta ( + Flute Concerto, Concerto Amoroso, Concerto Nostalgico and Nocturne for Cello and Strings) BIS CD-1579 (2009) Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1998) Leonard Slatkin/Orchestre National de France ( + Henderson: Einstein's Violin, El Khoury: Les Fleuves Engloutis, Maskats: Tango, Plate: You Must Finish Your Journey Alone, and Theofanidis: Rainbow Body) GRAMOPHONE MASTE (2003) (issued by Gramophone Magazine) CLAUDE BALLIF (1924-2004) Born in Paris. His musical training began at the Bordeaux Conservatory but he went on to the Paris Conservatory where he was taught by Tony Aubin, Noël Gallon and Olivier Messiaen. -

Salt Lake City August 1—4, 2019 Nfac Discover 18 Ad OL.Pdf 1 6/13/19 8:29 PM

47th Annual National Flute Association Convention Salt Lake City August 1 —4, 2019 NFAc_Discover_18_Ad_OL.pdf 1 6/13/19 8:29 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Custom Handmade Since 1888 Booth 110 wmshaynes.com Dr. Rachel Haug Root Katie Lowry Bianca Najera An expert for every f lutist. Three amazing utists, all passionate about helping you und your best sound. The Schmitt Music Flute Gallery offers expert consultations, easy trials, and free shipping to utists of all abilities, all around the world! Visit us at NFA booth #126! Meet our specialists, get on-site ute repairs, enter to win prizes, and more. schmittmusic.com/f lutegallery Wiseman Flute Cases Compact. Strong. Comfortable. Stylish. And Guaranteed for life. All Wiseman cases are hand- crafted in England from the Visit us at finest materials. booth 214 in All instrument combinations the exhibit hall, supplied – choose from a range of lining colours. Now also NFA 2019, Salt available in Carbon Fibre. Lake City! Dr. Rachel Haug Root Katie Lowry Bianca Najera An expert for every f lutist. Three amazing utists, all passionate about helping you und your best sound. The Schmitt Music Flute Gallery offers expert consultations, easy trials, and free shipping to utists of all abilities, all around the world! Visit us at NFA booth #126! Meet our specialists, get on-site ute repairs, enter to win prizes, and more. 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 [email protected] schmittmusic.com/f lutegallery www.wisemanlondon.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Committees ............................................................... -

Utah Symphony | Utah Opera

Media Contact: Renée Huang | Public Relations Director [email protected] | (801) 869-9027 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: UTAH SYMPHONY PRESENTS BERLIOZ’S DAMNATION OF FAUST WITH ACCLAIMED GUEST OPERA SOLOISTS KATE LINDSEY AND MICHAEL SPYRES SALT LAKE CITY, Utah (Sept.12, 2013) – Mezzo Soprano Kate Lindsey, a veteran of the Metropolitan Opera, and Michael Spyres, called “one of today’s finest tenors” by French Opera magazine join the Utah Symphony on September 27 and 28 at Abravanel Hall in Hector Berlioz’s dramatic interpretation of Goethe’s tale of Faust and his fateful deal with the devil, The Damnation of Faust. The Utah Symphony Chorus and Utah Opera Chorus lend their voices to the work, which is an ingenious combination of opera and oratorio that ranks among Berlioz’s finest creations. In addition to the star power of Lindsey and Spyres who sings the role of Marguerite and Faust, three other operatic guest artists will join the cast, including Baritone Roderick Williams, whose talents have included appearances with all BBC orchestras, London Sinfonietta and the Philharmonia, performing Mephistopheles; and Bass- baritone Adam Cioffari, a former member of the Houston Grand Opera Studio. Newcomer Tara Stafford Spyres, a young coloratura soprano, just sang her first Mimi in Springfield Missouri’s Regional Opera production of La Bohème. La Damnation de Faust was last performed on the Utah Symphony Masterworks Series in 2003 as part of the company’s Faust Festival. TICKET INFORMATION Single tickets for the performance range from $18 to $69 and can be purchased by phone at (801) 355- 2787, in person at the Abravanel Hall ticket office (123 W. -

Symphonie Fantastique

CLASSICAL�SERIES SYMPHONIE FANTASTIQUE THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 7, AT 7 PM FRIDAY & SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 8 & 9, AT 8 PM NASHVILLE SYMPHONY THIERRY FISCHER, conductor STEPHEN HOUGH, piano ANDREW NORMAN Unstuck – 10 minutes FELIX MENDELSSOHN Concerto No. 1 in G Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 25 – 21 minutes Molto allegro con fuoco Andante Presto – Molto allegro e vivace Stephen Hough, piano – INTERMISSION – HECTOR BERLIOZ Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14 – 49 minutes Reveries and Passions A Ball Scene In the Country March to the Scaff old Dream of a Witches' Sabbath This concert will last one hour and 55 minutes, including a 20-minute intermission. This concert will be recorded live for future broadcast. To ensure the highest-quality recording, please keep noise to a minimum. INCONCERT 19 CLASSICAL PROGRAM SUMMARY How do young artists find a unique voice? This program brings together three works, each written when their respective composers were only in their 20s. The young American Andrew Norman was already tapping into his gift for crafting vibrantly imaginative, almost hyper-active soundscapes in Unstuck, the brief but event-filled orchestral piece that opens our concert. Felix Mendelssohn had already been in the public eye as a child prodigy before he embarked on a series of travels across Europe from which he stored impressions for numerous mature compositions — including the First Piano Concerto. Just around the time Mendelssohn wrote this music, his contemporary Hector Berlioz was refining the ideas that percolate in his first completed symphonic masterpiece. The Symphonie fantastique created a sensation of its own with its evocation of a tempestuous autobiographical love affair through an unprecedentedly bold use of the expanded Romantic orchestra. -

National Conference Performing Choirs

National Conference Performing Choirs 20152015 ACDA FestivalFestival ChoirChoir UniversityUniversity ofof Utah A Cappella Choir Thursday 8:00 pm - 9:45 pm Abravanel Hall (Blue Track) Friday 8:00 pm - 9:45 pm Abravanel Hall (Gold Track) The 2015 ACDA Festival Choir includes the Utah Sym- phony Chorus, Utah Chamber Artists, the University of Utah Chamber Choir, and the University of Utah A Cappella Choir conducted by Barlow Bradford. The Utah Symphony is con- ducted by Thierry Fischer. Founded in 1962, the A Cappella Choir offers singers the opportunity to perform works for larger choirs and to fi ne- tune the art of choral singing through exposure to music from Utah Chamber Artists the Renaissance through the twenty-fi rst century. Choir mem- bers hone musicianship skills such as rhythm, sight-reading, and the understanding of complex scores. They develop an understanding of the intricacies of vocal production, includ- ing pitch, and how to blend individual voices together into a unifi ed, beautiful sound. In recent years, the A Cappella Choir has become a standard of excellence in student singing in the State of Utah. Last fall, they sang Mozart’s Trinity Mass with the Utah Symphony and the Utah Symphony Chorus under the direction of Thierry Fischer. This renewed a tradition of collaboration between the choirs of the University of Utah and the Utah Symphony, and their outstanding performance resulted in invitations for return engagements in 2015. Utah Chamber Artists was established in 1991 by Barlow University of Utah Chamber Choir Bradford and James Lee Sorenson. The ensemble comprises forty singers and forty players who create a balance and so- nority rarely found in a combined choir and orchestra. -

New Publications

NEW PUBLICATIONS ARTICLES Kater, Michael H. 'The Revenge of the Fathers: The Demise of Modern Music at the End of the Weimar Republic." German Studies Review 15, no. 2 (May 1992): 295-313. Lareau, Alan. "1ne German Cabaret Movement During the Weimar Republic." Theatre journal 43 (1991): 471-90. · Lucchesi, Joachim. "Contextualizing The Threepenny Opera: Music and Politics." Com munications from the international Brecht Society 21, no. 2 (November 1992): 45-48. Lucchesi, Joachim. " ... ob Sie noch deutscher lnlander sind? Der Komponist Kurt Weill im Exil." Ko"espondenzen 11-12-13 (1992): 42-44. Published by the Gesellschaft fur Theaterpadagogik Niedersachsen, Hannover. Stempel, Larry. 'The Musical Play Expands." American Music 10, no. 2 (Summer 1992): 13&-69. Stern, Guy and Peter Schon back. "Die Vertonung Werfelscher Dramen." ln Franz We,fel im Exit, edited by Wolfgang Nehring and Hans Wagener, 187-98. Bonn: Bouvier, 1992. Wagner, Gottfried. "ll teatro de Weill e Brecht." Musica e Dossier41 Oune 1990): 74-79. WiBkirchen, Hubert. "Mimesis und Gestus: Das 'Llebeslied' aus der Dreigroschenoper (Brecht/Weill)." Musik und Unterricht 5 (1990): 38-44. BOOKS Jacob, P. Walter. Musica Prohibida-Verbotene Musik: Ein Vortrag im Exit. Hrsg. und kommentiert von Kritz Pohle (Schriftenreihe des P. Walter Jocob-Archivs. nr. 3). Hamburg: Hamburger Arbeitsstelle fur deutsche Exilliteratur, 1991. Wagner, Gottfried. Weill e Brecht. Pordenone, Italy: Studio Tesi, 1992. Weill, Kurt Kurt Weill:de Berlin aBroadway. Traduitetpresentepar Pascal Huynh. Paris: Editions Plume, 1993. RECORDINGS ''Kurt Weill: Un Pianoforte a Broadway." Roberto Negri, piano. Riverrecords CDR 5405. "Laura Goes Weill" Laura Goes Blue (rock ensemble). Industrial Jive Records 04-14-92- 01. -

The Future of Higher Education

ANNUAL NEWSLETTER CONCEPTUAL RENDERING THE FUTURE OF HIGHER EDUCATION THE HINCKLEY INSTITUTE’S FUTURE HOME PLANNING FOR THE PRICE INTERNATIONAL PAVILION LAUNCH OF THE SAM RICH LECTURE SERIES MALCOLM GLADWELL’S VISION FOR COMPETITIVE STUDENTS OFFICE FOR GLOBAL ENGAGEMENT PARTNERSHIP THE U’S GLOBAL INTERNSHIPS POISED FOR MASSIVE GROWTH 2013 SICILIANO FORUM EDUCATION EXPERTS CONVERGE FOR FULL WEEK table of contents NEW & NOTEWORTHY: 4 HINCKLEY FELLOWS 5 DIGNITARIES 44 HINCKLEY HAPPENINGS: 8 HINCKLEY PRESENCE 10 HINCKLEY FORUMS 8 THE FUTURE OF HIGHER ED: 12 OUR VISION 14 PRICE INTERNATIONAL BUILDING 15 OUR NEW PARTNERSHIP 16 16 SICILIANO FORUM 18 SAM RICH LECTURE SERIES 1414 HINCKLEY TEAM: 20 OUR INTERNS 30 OUR STAFF 31 31 PORTRAIT UNVEILING Contributing Editors: Ellesse S. Balli Rochelle M. Parker Lisa Hawkins Kendahl Melvin Leo Masic Art Director: Ellesse S. Balli MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR Malcolm Gladwell. Dubbed by the seven short years since we KIRK L. JOWERS Time magazine as “one of the 100 launched our global internship most influential people” in the program, we have placed more world and by Foreign Policy as than 400 students in almost 60 a leading “top global thinker,” countries across the globe. It is Gladwell discussed the advantages now celebrated as the best political of disadvantages in a sold-out and humanitarian internship pro- event at Abravanel Hall. gram in the U.S. Culminating this Gladwell’s findings confirmed achievement, this year the Hinck- my belief that it is far better for ley Institute was charged with undergraduates to be a “big fish” overseeing all University of Utah within the University of Utah and campus global internships in part- Hinckley Institute than a “little nership with the new Office for fish” at an Ivy League school. -

Curriculum Vitae

Barlow Bradford (801) 587-9377 office (801) 556-8422 mobile www.barlowbradford.com [email protected] Education 1996 D.M.A. Keyboard Collaborative Arts University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California Major Teacher: Kevin Fitz-Gerald 1988 M.M. Orchestral Conducting University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California Major Teacher: Daniel Lewis 1985 B.M. Piano Performance University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah Major Teacher: Gladys Gladstone Professional Preparation and Private Training 1990-1993 Orchestral Conducting with Gustav Meier, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan Tanglewood Summer Music Institute, Lennox, Massachusetts 1986 Orchestral Conducting (Conducting Fellow) with Paul Vermel Aspen Music Festival, Aspen, Colorado 1982-1987 Piano Performance with Nina Svetlanova Mannes College of Music, New York, New York 1977-1978 Theory/Composition with Robert Cundick Tabernacle Organist, Salt Lake City, Utah 1971-1979 Piano Performance with Gladys Gladstone University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 1971-1977 Organ Performance with Clay Christiansen Tabernacle Organist, Salt Lake City, Utah Honors, Awards and Grants 2016 ‘Celebrate U’ Outstanding faculty award 2016 Touring grant ($20,000) from Anonymous donor 2015 Gran Prix Winner at the European Gran Prix for Choral Singing, Tours, France 2015 Touring Grant, ($90,000) awarded to send the University of Utah Chamber Choir to France to participate in the European Gran Prix International Choral Competition. Combined sources from Kem and Carolyn Gardner, Scott Anderson, Eccles Foundation, Wheeler Foundation, University of Utah Office of the President, University of Utah College of Fine Arts 1 2014 Gran Prix Winner and the Audience Favorite Award at the Florilege International Choral Competition, Tours, France 2014 Dee Grant, ($10,000) awarded to partially fund a major choral/orchestral work from Eriks Esenvalds, internationally known composer. -

Acoustics of the Great Hall of the Moscow State Conservatory After Reconstruction in 2010–2011 by N

www.akutek.info PRESENTS Acoustics of the Great Hall of the Moscow State Conservatory after Reconstruction in 2010–2011 by N. G. Kanev, A. Ya. Livshits, and H. Möller Introduction The Great Hall of the Moscow State Conservatory was built in the early 20th century. For more than 100 years of service, it had a high acoustic reputation both among musicians and audience. By the beginning of the 21st century, the hall was in nearly critical condition. Thus, major renovation was needed. In terms of architectural acoustics, the main task was to keep the good acoustics of the hall. This paper presents the results of acoustic parameter measurements of the hall after Reconstruction in 2010–2011. The parameters of the hall measured before and after reconstruction are also compared. The comparative acoustic characteristics between the Great Hall and world leading concert halls are given. The reconstruction of the Grand Hall of the Moscow Conservatory in 2010–2011 did not have a significant impact on its acoustics. The acoustic quality of the hall remained at the same high level, which has been confirmed by acoustic parameter measurements before and after renovation. Small differences in some parameters at low and high frequencies can be interpreted as positive, since they made it possible to balance the frequency response of these parameters. Performers and listeners appreciated the acoustics of the Great Hall after renovation. No one noted deterioration in the acoustic characteristics. akuTEK navigation: Home Papers Title Index akuTEK research Concert Hall Acoustics ISSN 10637710, Acoustical Physics, 2013, Vol. 59, No. 3, pp. 361–368.