John Dalton, the Man and His Legacy: the Bicentenary of His Atomic Theory†

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literature Compass Editing Humphry Davy's

1 ‘Work in Progress in Romanticism’ Literature Compass Editing Humphry Davy’s Letters Tim Fulford, Andrew Lacey, Sharon Ruston An editorial team of Tim Fulford (De Montfort University) and Sharon Ruston (Lancaster University) (co-editors), and Jan Golinski (University of New Hampshire), Frank James (the Royal Institution of Great Britain), and David Knight1 (Durham University) (advisory editors) are currently preparing The Collected Letters of Sir Humphry Davy: a four-volume edition of the c. 1200 surviving letters of Davy (1778-1829) and his immediate circle, for publication with Oxford University Press, in both print and electronic forms, in 2020. Davy was one of the most significant and famous figures in the scientific and literary culture of early nineteenth-century Britain, Europe, and America. Davy’s scientific accomplishments were varied and numerous, including conducting pioneering research into the physiological effects of nitrous oxide (laughing gas); isolating potassium, calcium, and several other metals; inventing a miners’ safety lamp (the bicentenary of which was celebrated in 2015); developing the electrochemical protection of the copper sheeting of Royal Navy vessels; conserving the Herculaneum papyri; writing an influential text on agricultural chemistry; and seeking to improve the quality of optical glass. But Davy’s endeavours were not merely limited to science: he was also a poet, and moved in the same literary circles as Lord Byron, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Robert Southey, and William Wordsworth. Since his death, Davy has rarely been out of the public mind. He is still the frequent subject of biographies (by, 1 David Knight died in 2018. David gave generously to the Davy Letters Project, and a two-day conference at Durham University was recently held in his memory. -

Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary Journal Item How to cite: Stenhouse, Brigitte (2020). Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary. The Mathematical Intelligencer (Early Access). For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2020 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1007/s00283-020-09998-6 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary BRIGITTE STENHOUSE ary Somerville’s life as a mathematician and mathematician). Although no scientific learned society had a savant in nineteenth-century Great Britain was formal statute barring women during Somerville’s lifetime, MM heavily influenced by her gender; as a woman, there was nonetheless a great reluctance even toallow women her access to the ideas and resources developed and into the buildings, never mind to endow them with the rights circulated in universities and scientific societies was highly of members. Except for the visit of the prolific author Margaret restricted. However, her engagement with learned institu- Cavendish in 1667, the Royal Society of London did not invite tions was by no means nonexistent, and although she was women into their hallowed halls until 1876, with the com- 90 before being elected a full member of any society mencement of their second conversazione [15, 163], which (Societa` Geografica Italiana, 1870), Somerville (Figure 1) women were permitted to attend.1 As late as 1886, on the nevertheless benefited from the resources and social nomination of Isis Pogson as a fellow, the Council of the Royal networks cultivated by such institutions from as early as Astronomical Society chose to interpret their constitution as 1812. -

Atomic History Project Background: If You Were Asked to Draw the Structure of an Atom, What Would You Draw?

Atomic History Project Background: If you were asked to draw the structure of an atom, what would you draw? Throughout history, scientists have accepted five major different atomic models. Our perception of the atom has changed from the early Greek model because of clues or evidence that have been gathered through scientific experiments. As more evidence was gathered, old models were discarded or improved upon. Your task is to trace the atomic theory through history. Task: 1. You will create a timeline of the history of the atomic model that includes all of the following components: A. Names of 15 of the 21 scientists listed below B. The year of each scientist’s discovery that relates to the structure of the atom C. 1- 2 sentences describing the importance of the discovery that relates to the structure of the atom Scientists for the timeline: *required to be included • Empedocles • John Dalton* • Ernest Schrodinger • Democritus* • J.J. Thomson* • Marie & Pierre Curie • Aristotle • Robert Millikan • James Chadwick* • Evangelista Torricelli • Ernest • Henri Becquerel • Daniel Bernoulli Rutherford* • Albert Einstein • Joseph Priestly • Niels Bohr* • Max Planck • Antoine Lavoisier* • Louis • Michael Faraday • Joseph Louis Proust DeBroglie* Checklist for the timeline: • Timeline is in chronological order (earliest date to most recent date) • Equal space is devoted to each year (as on a number line) • The eight (8) *starred scientists are included with correct dates of their discoveries • An additional seven (7) scientists of your choice (from -

The Politics of Medicine in Manchester, 1788-1792: Hospital Reform and Public Health Services in the Early Industrial City

Medical History, 1984, 28: 227-249 THE POLITICS OF MEDICINE IN MANCHESTER, 1788-1792: HOSPITAL REFORM AND PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICES IN THE EARLY INDUSTRIAL CITY by J. V. PICKSTONE and S. V. F. BUTLER* The affairs of the Infirmary and Lunatic Hospital continued till Michaelmas 1790 when a particular scrutiny was made into the Rules and Government of the Charities; and so many additions and altera- tions made in them that almost an entire New System was introduced. Six Physicians and Six Surgeons were then appointed to manage the whole business of their profession. Compleat Assistance was provided for the Poor in every Malady to which they are Subject and for which the Art of Man has yet found a remedy.' BY 1790, the Manchester Infirmary had existed for almost forty years. It had been founded in 1752, one of a series of voluntary hospitals which had spread across the provinces in the 1750s and 1760s.2 They were the central charities in increasingly prosperous towns, means by which leading citizens could demonstrate a collective responsibility for the poor, and arenas in which physicians and the better-qualified surgeons could establish a public presence and demonstrate their skills. In 1780, there was little to distinguish Manchester's Infirmary from those in many county towns, which were to continue little changed for a century or so. The Infirmary revolution of 1790 came about because Manchester had begun to change rapidly. The 1780s saw a large inflow of capitalists and labourers, and with them came professional men, including Scottish-trained physicians anxious to use their scientific training to create successful careers among the rising bourgeoisie. -

Philosophical Transactions, »

INDEX TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS, » S e r ie s A, FOR THE YEAR 1898 (VOL. 191). A. Absorption, Change of, produced by Fluorescence (B urke), 87. Aneroid Barometers, Experiments on.—Elastic After-effect; Secular Change; Influence of Temperature (Chree), 441. B. Bolometer, Surface, Construction of (Petavel), 501. Brilliancy, Intrinsic, Law of Variation of, with Temperature (Petavel), 501. Burke (John). On the Change of Absorption produced by Fluorescence, 87. C. Chree (C.). Experiments on Aneroid Barometers at Kew Observatory, and their Discussion, 441. Correlation and Variation, Influence of Random Selection on (Pearson and Filon), 229. Crystals, Thermal Expansion Coefficients, by an Interference Method (Tutton), 313. D. Differential Equations of the Second Order, &c., Memoir on the Integration of; Characteristic Invariant of (Forsyth), 1. 526 INDEX. E. Electric Filters, Testing Efficiency of; Dielectrifying Power of (Kelvin, Maclean, and Galt), 187. Electricity, Diffusion of, from Carbonic Acid Gas to Air; Communication of, from Electrified Steam to Air (Kelvin, Maclean, and Galt), 187. Electrification of Air by Water Jet, Electrified Needle Points, Electrified Flame, &c., at Different Air-pressures; at Different Electrifying Potentials; Loss of Electrification (Kelvin, Maclean, and Galt), 187. Electrolytic Cells, Construction and Calibration of (Veley and Manley), 365. Emissivity of Platinum in Air and other Gases (Petavel), 501. Equations, Laplace's and other, Some New Solutions of, in Mathematical Physics (Forsyth), 1. Evolution, Mathematical Contributions to Theory o f; Influence of Random Selection on the Differentiation of Local Races (Pearson and Filon), 229. F. Filon (L. N. G.) and Pearson (Karl). Mathematical Contributions to the Theory of Evolution.—IV. On the Probable Errors of Frequency Constants and on the Influence of Random Selection on Variation and Correlation, 229. -

John Dalton By: Period 8 Early Years and Education

John Dalton By: Period 8 Early Years and Education • John Dalton was born in the small British village of Eaglesfield, Cumberland, England to a Quaker family. • As a child, John did not have much formal education because his family was rather poor; however, he did acquire a basic foundation in reading, writing, and arithmetic at a nearby Quaker school. • A teacher by the name of John Fletcher took young John Dalton under his wing and introduced him to a great mentor, Elihu Robinson, who was a rich Quaker. • Elihu then agreed to tutor John in mathematics, science, and meteorology. Shortly after he ended his tutoring sessions with Elihu, Dalton began keeping a daily log of the weather and other matters of meteorology. Education continued • His studies of these weather conditions led him to develop theories and hypotheses about mixed gases and water vapor. • He kept this journal of weather recordings his entire life, which later aided him in his observations and recordings of atoms and elements. Accomplishments • In 1794, Dalton became the first • Dalton joined the Manchester to explain color blindness, Literary and Philosophical which he was afflicted with Society and instantly published himself, at one of his public his first book on Meteorological lectures and it is even Observations and Essays. sometimes called Daltonism referring to John Dalton • In this book, John tells of his himself. ideas on gasses and that “in a • The first paper he wrote on this mixture of gasses, each gas matter was entitled exists independently of each Extraordinary facts relating to other gas and acts accordingly,” the visions of colors “in which which was when he’s famous he postulated that shortage in ideas on the Atomic Theory color perception was caused by started to form. -

Atomic Theories and Models

Atomic Theories and Models Answer these questions on your own. Early Ideas About Atoms: Go to http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0905226.html and read the section on “Greek Origins” in order to answer the following: 1. What were Leucippus and Democritus ideas regarding matter? 2. Describe what these philosophers thought the atom looked like? 3. How were the ideas of these two men received by Aristotle, and what was the result on the progress of atomic theory for the next couple thousand years? Alchemists: Go to http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/alchemy and/or http://www.scienceandyou.org/articles/ess_08.shtml to answer the following: 4. What was the ultimate goal of an alchemist? 5. What is the word used to describe changing something of little value into something of higher value? 6. Did any alchemist achieve this goal? John Dalton’s Atomic Theory: Go to http://www.rsc.org/chemsoc/timeline/pages/1803.html and answer the following: 7. When did Dalton form his atomic theory. 8. List the six ideas of Dalton’s theory: a. b. c. d. e. f. Mendeleev: Go to http://www.chemistry.co.nz/mendeleev.htm and/or http://www.aip.org/history/curie/periodic.htm to answer the following: 9. What was Mendeleev’s famous contribution to chemistry? 10. How did Mendeleev arrange his periodic table? 11. Why did Mendeleev leave blank spaces in his periodic table? J. J. Thomson: Go to http://www.universetoday.com/38326/plum-pudding-model/ and http://www.chemheritage.org/discover/online-resources/chemistry-in-history/themes/atomic-and- nuclear-structure/thomson.aspx and http://www.chem.uiuc.edu/clcwebsite/cathode.html and http://www-outreach.phy.cam.ac.uk/camphy/electron/electron_index.htm and http://www.iun.edu/~cpanhd/C101webnotes/modern-atomic-theory/rutherford-model.html to answer the following: 12. -

1 Classical Theory and Atomistics

1 1 Classical Theory and Atomistics Many research workers have pursued the friction law. Behind the fruitful achievements, we found enormous amounts of efforts by workers in every kind of research field. Friction research has crossed more than 500 years from its beginning to establish the law of friction, and the long story of the scientific historyoffrictionresearchisintroducedhere. 1.1 Law of Friction Coulomb’s friction law1 was established at the end of the eighteenth century [1]. Before that, from the end of the seventeenth century to the middle of the eigh- teenth century, the basis or groundwork for research had already been done by Guillaume Amontons2 [2]. The very first results in the science of friction were found in the notes and experimental sketches of Leonardo da Vinci.3 In his exper- imental notes in 1508 [3], da Vinci evaluated the effects of surface roughness on the friction force for stone and wood, and, for the first time, presented the concept of a coefficient of friction. Coulomb’s friction law is simple and sensible, and we can readily obtain it through modern experimentation. This law is easily verified with current exper- imental techniques, but during the Renaissance era in Italy, it was not easy to carry out experiments with sufficient accuracy to clearly demonstrate the uni- versality of the friction law. For that reason, 300 years of history passed after the beginning of the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century before the friction law was established as Coulomb’s law. The progress of industrialization in England between 1750 and 1850, which was later called the Industrial Revolution, brought about a major change in the production activities of human beings in Western society and later on a global scale. -

LXVIII. Notices Respecting New Books

Philosophical Magazine Series 1 ISSN: 1941-5796 (Print) 1941-580X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tphm12 LXVIII. Notices respecting new books To cite this article: (1812) LXVIII. Notices respecting new books , Philosophical Magazine Series 1, 40:175, 386-387, DOI: 10.1080/14786441208638253 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14786441208638253 Published online: 27 Jul 2009. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 2 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tphm12 Download by: [University of California, San Diego] Date: 29 June 2016, At: 12:41 aseJ Notices respecting New Books. Both fluid epmpounds , when healed, are rendered solicb from the expulsion of part of the ammonia. Exposure to l~he air is attended with the same change, and the same effect is produced by the mtlriatic and carbonic acid gases. Knowing the volumes of the acid, and alkaline gase~ which combine, it is easy to calculate the proportions of each by weight in the respective salts. 100 Paa'ts consist of Ammonia. Acid. The solid compound I1 19"64 ~o'3~ The first fluid ....... I 3~ 17"1 The second fluid ..... [ +~" ~,'~--1 t These combinations are curious in many points of view. They are the first salts that have been observed liquid, at the common temperature of the atmosphere, without con- taining water. And they are additional facts in suport of the doctrine of definite proportions, and of the relation o'f volumes. LXVI I I. Notices respect ing New Books. -

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY Theo James presenting a bouquet to HM The Queen on the occasion of her bicentenary visit, 7 December 1999. by Frank A.J.L. James The Director, Susan Greenfield, looks on Front page: Façade of the Royal Institution added in 1837. Watercolour by T.H. Shepherd or more than two hundred years the Royal Institution of Great The Royal Institution was founded at a meeting on 7 March 1799 at FBritain has been at the centre of scientific research and the the Soho Square house of the President of the Royal Society, Joseph popularisation of science in this country. Within its walls some of the Banks (1743-1820). A list of fifty-eight names was read of gentlemen major scientific discoveries of the last two centuries have been made. who had agreed to contribute fifty guineas each to be a Proprietor of Chemists and physicists - such as Humphry Davy, Michael Faraday, a new John Tyndall, James Dewar, Lord Rayleigh, William Henry Bragg, INSTITUTION FOR DIFFUSING THE KNOWLEDGE, AND FACILITATING Henry Dale, Eric Rideal, William Lawrence Bragg and George Porter THE GENERAL INTRODUCTION, OF USEFUL MECHANICAL - carried out much of their major research here. The technological INVENTIONS AND IMPROVEMENTS; AND FOR TEACHING, BY COURSES applications of some of this research has transformed the way we OF PHILOSOPHICAL LECTURES AND EXPERIMENTS, THE APPLICATION live. Furthermore, most of these scientists were first rate OF SCIENCE TO THE COMMON PURPOSES OF LIFE. communicators who were able to inspire their audiences with an appreciation of science. -

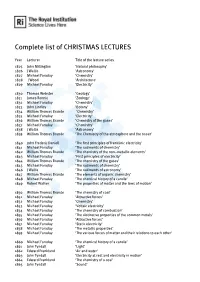

Complete List of CHRISTMAS LECTURES

Complete list of CHRISTMAS LECTURES Year Lecturer Title of the lecture series 1825 John Millington ‘Natural philosophy’ 1826 J Wallis ‘Astronomy’ 1827 Michael Faraday ‘Chemistry’ 1828 J Wood ‘Architecture’ 1829 Michael Faraday ‘Electricity’ 1830 Thomas Webster ‘Geology’ 1831 James Rennie ‘Zoology’ 1832 Michael Faraday ‘Chemistry’ 1833 John Lindley ‘Botany’ 1834 William Thomas Brande ‘Chemistry’ 1835 Michael Faraday ‘Electricity’ 1836 William Thomas Brande ‘Chemistry of the gases’ 1837 Michael Faraday ‘Chemistry’ 1838 J Wallis ‘Astronomy’ 1839 William Thomas Brande ‘The Chemistry of the atmosphere and the ocean’ 1840 John Frederic Daniell ‘The first principles of franklinic electricity’ 1841 Michael Faraday ‘The rudiments of chemistry’ 1842 William Thomas Brande ‘The chemistry of the non–metallic elements’ 1843 Michael Faraday ‘First principles of electricity’ 1844 William Thomas Brande ‘The chemistry of the gases’ 1845 Michael Faraday ‘The rudiments of chemistry’ 1846 J Wallis ‘The rudiments of astronomy’ 1847 William Thomas Brande ‘The elements of organic chemistry’ 1848 Michael Faraday ‘The chemical history of a candle’ 1849 Robert Walker ‘The properties of matter and the laws of motion’ 1850 William Thomas Brande ‘The chemistry of coal’ 1851 Michael Faraday ‘Attractive forces’ 1852 Michael Faraday ‘Chemistry’ 1853 Michael Faraday ‘Voltaic electricity’ 1854 Michael Faraday ‘The chemistry of combustion’ 1855 Michael Faraday ‘The distinctive properties of the common metals’ 1856 Michael Faraday ‘Attractive forces’ 1857 Michael Faraday -

the Papers Philosophical Transactions

ABSTRACTS / OF THE PAPERS PRINTED IN THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF LONDON, From 1800 to1830 inclusive. VOL. I. 1800 to 1814. PRINTED, BY ORDER OF THE PRESIDENT AND COUNCIL, From the Journal Book of the Society. LONDON: PRINTED BY RICHARD TAYLOR, RED LION COURT, FLEET STREET. CONTENTS. VOL. I 1800. The Croonian Lecture. On the Structure and Uses of the Meinbrana Tympani of the Ear. By Everard Home, Esq. F.R.S. ................page 1 On the Method of determining, from the real Probabilities of Life, the Values of Contingent Reversions in which three Lives are involved in the Survivorship. By William Morgan, Esq. F.R.S.................... 4 Abstract of a Register of the Barometer, Thermometer, and Rain, at Lyndon, in Rutland, for the year 1798. By Thomas Barker, Esq.... 5 n the Power of penetrating into Space by Telescopes; with a com parative Determination of the Extent of that Power in natural Vision, and in Telescopes of various Sizes and Constructions ; illustrated by select Observations. By William Herschel, LL.D. F.R.S......... 5 A second Appendix to the improved Solution of a Problem in physical Astronomy, inserted in the Philosophical Transactions for the Year 1798, containing some further Remarks, and improved Formulae for computing the Coefficients A and B ; by which the arithmetical Work is considerably shortened and facilitated. By the Rev. John Hellins, B.D. F.R.S. .......................................... .................................. 7 Account of a Peculiarity in the Distribution of the Arteries sent to the ‘ Limbs of slow-moving Animals; together with some other similar Facts. In a Letter from Mr.