Uinta National Forest State of the Forest Report for Fiscal Year 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Formation of Fluvial Islands

AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF Joshua R. Wyrick for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Civil Engineering presented on March 31, 2005. Title: On the Formation of Fluvial Islands Abstract approved: Signature redacted for privacy. Peter C. Klingeman This research analyzes the effects of islands on river process and the effects river processes have on island formation. A fluvial island is defined herein as a land mass within a river channel that is separated from the floodplain by water on all sides, exhibits some stability, and remains exposed during bankfull flow. Fluvial islands are present in nearly all major rivers. They must therefore have some impact on the fluid mechanics of the system, and yet there has never been a detailed study on fluvial islands.Islands represent a more natural state of a river system and have been shown to provide hydrologic variability and biotic diversity for the river. This research describes the formation of fluvial islands, investigates the formation of fluvial islands experimentally, determines the main relations between fluvial islands and river processes, compares and describes relationships between fluvial islands and residual islands found in megaflood outwash plains, and reaches conclusions regarding island shape evolution and flow energy loss optimization. Fluvial islands are known to form by at least nine separate processes: avulsion, gradual degradation of channel branches, lateral shifts in channel position, stabilization of a bar or riffle, isolation of structural features, rapid incision of flood deposits, sediment deposition in the lee of an obstacle, isolation of material deposited by mass movement, and isolation of riparian topography after the installation of a dam. -

443 Subpart D—Federally Promulgated Water Quality Standards

Environmental Protection Agency § 131.33 Subpart D—Federally Promulgated of streams located in Indian country, Water Quality Standards or as may be modified by the Regional Administrator, EPA Region X, pursu- § 131.31 Arizona. ant to paragraph (a)(3) of this section, ° (a) [Reserved] a temperature criterion of 10 C, ex- (b) The following waters have, in ad- pressed as an average of daily max- dition to the uses designated by the imum temperatures over a seven-day State, the designated use of fish con- period, applies to the waterbodies iden- sumption as defined in R18–11–101 tified in paragraph (a)(2) of this section (which is available from the Arizona during the months of June, July, Au- Department of Environmental Quality, gust and September. Water Quality Division, 3033 North (2) The following waters are pro- Central Ave., Phoenix, AZ 85012): tected for bull trout spawning and rearing: COLORADO MAIN STEM RIVER (i) BOISE-MORE BASIN: Devils BASIN: Creek, East Fork Sheep Creek, Sheep Hualapai Wash MIDDLE GILA RIVER BASIN: Creek. Agua Fria River (Camelback Road to (ii) BROWNLEE RESERVOIR BASIN: Avondale WWTP) Crooked River, Indian Creek. Galena Gulch (iii) CLEARWATER BASIN: Big Can- Gila River (Felix Road to the Salt yon Creek, Cougar Creek, Feather River) Creek, Laguna Creek, Lolo Creek, Queen Creek (Headwaters to the Su- Orofino Creek, Talapus Creek, West perior WWTP) Fork Potlatch River. Queen Creek (Below Potts Canyon) (iv) COEUR D’ALENE LAKE BASIN: SAN PEDRO RIVER BASIN: Cougar Creek, Fernan Creek, Kid Copper Creek Creek, Mica Creek, South Fork Mica SANTA CRUZ RIVER BASIN: Creek, Squaw Creek, Turner Creek. -

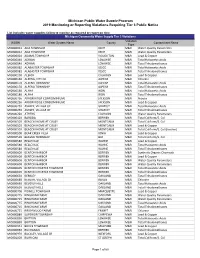

2019 Monitoring Or Reporting Violations Requiring Tier 3 Public Notice

Michigan Public Water Supply Program 2019 Monitoring or Reporting Violations Requiring Tier 3 Public Notice List includes water supplies failing to monitor as required or report on time. Michigan Community Water Supply Tier 3 Violations Violation WSSN Water System Name County Contaminant Name Type MI0000012 ADA TOWNSHIP KENT M&R Water Quality Parameters MI0000012 ADA TOWNSHIP KENT M&R Water Quality Parameters MI0000020 ADAMS TOWNSHIP HOUGHTON M&R Lead & Copper MI0000040 ADRIAN LENAWEE M&R Total Haloacetic Acids MI0000040 ADRIAN LENAWEE M&R Total Trihalomethanes MI0000082 ALABASTER TOWNSHIP IOSCO M&R Total Haloacetic Acids MI0000082 ALABASTER TOWNSHIP IOSCO M&R Total Trihalomethanes MI0000100 ALBION CALHOUN M&R Lead & Copper MI0000160 ALPENA, CITY OF ALPENA M&R Chlorine MI0000170 ALPENA TOWNSHIP ALPENA M&R Total Haloacetic Acids MI0000170 ALPENA TOWNSHIP ALPENA M&R Total Trihalomethanes MI0000180 ALPHA IRON M&R Total Haloacetic Acids MI0000180 ALPHA IRON M&R Total Trihalomethanes MI0000236 ARBOR RIDGE CONDOMINIUMS JACKSON M&R Nitrate MI0000236 ARBOR RIDGE CONDOMINIUMS JACKSON M&R Lead & Copper MI0000250 ASHLEY, VILLAGE OF GRATIOT M&R Total Haloacetic Acids MI0000250 ASHLEY, VILLAGE OF GRATIOT M&R Total Trihalomethanes MI0000260 ATHENS CALHOUN M&R Water Quality Parameters MI0000420 BARODA BERRIEN M&R Total Coliform/E. Coli MI0000503 BEACON HOME AT COLBY MONTCALM M&R Total Coliform/E. Coli MI0000503 BEACON HOME AT COLBY MONTCALM M&R Lead & Copper MI0000503 BEACON HOME AT COLBY MONTCALM M&R Total Coliform/E. Coli (source) MI0000508 BEAR CREEK -

Fish Order 210.21 Trout Streams

STATE OF MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES LANSING GRETCHEN WHITMER DANIEL EICHINGER GOVERNOR DIRECTOR A P P R O V E D ______________________,20____ SUBMITTED: July 20, 2020 MICHIGAN NATURAL RESOURCES COMMISSION RESUBMITTED: August 17, 2020 _____________________________ (ASSISTANT TO THE COMMISSION) MEMORANDUM TO THE NATURAL RESOURCES COMMISSION Subject: Fisheries Order 210.21 Designated Trout Streams for Michigan Authority: The Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act, 1994 PA 451, authorizes the Director and the Commission to issue Orders to regulate the taking of fish in the waters of this state. Discussion and Background: Fisheries Order 210 governs designated trout streams in Michigan. Fisheries Division recommends adding one stream to the Order and removing one stream from the Order. Carter Creek in Roscommon County has recently been surveyed where a thriving brook trout population has been documented. Adding Carter Creek to the Order will result in greater protection of brook trout by placing it into Type 1 trout fishing regulations. This will place a fishing and possession season from the last Saturday in April through September 30. The closed season will protect brook trout when they are most vulnerable during spawning season. Wright Creek in Oscoda County has been recommended for removal since the habitat is not suitable for trout. Several fisheries surveys have failed to document any trout and temperature data indicates that this is a warmwater stream which will not support trout. Removing Wright Creek will result in defaulting to general statewide fishing regulations open all year to fishing. Issue Pros and Cons Adding a stream to this Order will result in placing more protective fishing regulations on a valued trout population. -

STATE of MARYLAND BOARD of NATURAL RESOURCES DEPARTMENT of GEOLOGY, MINES and WATER RESOURCES Joseph T

STATE OF MARYLAND BOARD OF NATURAL RESOURCES DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY, MINES AND WATER RESOURCES Joseph T. Singewald, Jr., Director BULLETIN 6 SHORE EROSION IN TIDEWATER MARYLAND CaliforniaState Division of Mines RECEIVED JAN 2 41950 library San Francisco, California BALTIMORE, MARYLAND 1949 Composed and Printed at Waverly Press, Inc. Baltimore, Md., U.S.A. COMMISSION ON GEOLOGY, MINES AND WATER RESOURCES Arthue B. Stewart, Chairman Baltimore Holmes D. Baker Frederick Harry R. Hall Hyattsville Joseph C. Lore, Jr Solomons Island Mervin A. Pentz Denton CONTENTS The Shore Erosion Problem. By Joseph T. Singewald, Jr 1 The Maryland Situation 1 Federal Legislation 2 Policy in Other Slates 2 Uniqueness of the Maryland Problem 3 Shore Erosion Damage in Maryland 4 Methods of Shore Front Protection 4 Examples of Shore Erosion Problems 6 Miami Beach 6 New Bay Shore Park 8 Mountain Point, Gibson Island 10 Tall Timbers, Potomac River 12 Tydings on the Bay and Log Inn, Anne Arundel County 14 Sandy Point State Park 15 What Should be done about Shore Erosion 16 The Shore Erosion Measurements. By Turhit H. Slaughter 19 Definition of Terms 19 Anne Arundel County 21 Baltimore County 28 Calvert County 31 Caroline County 35 Cecil County 37 Charles County 40 Dorchester County. 45 Harford County 54 Kent County 61 Prince Georges County 66 Queen Annes County 69 St. Marys County 75 Somerset County 84 Talbot County 91 Wicomico County 107 Worcester County 109 Summary of Shore Erosion in Tidewater Maryland 115 Navigation Restoration Expenditures. By Turbit If. Slaughter 119 References 121 Description of Plates 29 to 35 123 LIST OF TABLES 1. -

NY State Highway Bridge Data: August 31, 2021

NY State Highway Bridge Data: August 31, 2021 Otsego County Year Date BIN Built or of Last Poor Region County Municipality Location Feature Carried Feature Crossed Owner Replaced Inspectio Status n 09 Otsego Brookfield (Town) 3354020 HAMLET OF W EDMESTON WELCH ROAD UNADILLA RIVER 30 - County 1932 07/28/2020 N 09 Otsego Burlington (Town) 1026440 3 MI N WEST BURLINGTON 51 51 94021280 WHARTON CREEK NYSDOT 1994 07/13/2020 N 09 Otsego Burlington (Town) 1026450 2.3 MI SW OF WEST EXETER 51 51 94021302 BINGHAM RD CREEK NYSDOT 1934 05/29/2019 N 09 Otsego Burlington (Town) 1030850 0.5 MI W WEST BURLINGTON 80 80 94041102 WHARTON CREEK NYSDOT 1994 04/21/2020 N 09 Otsego Burlington (Town) 1030860 AT BURLINGTON 80 80 94041145 BUTTERNUT CREEK NYSDOT 2016 11/18/2020 N 09 Otsego Burlington (Town) 3369520 2 MI N BURLINGTON FLATS COUNTY ROAD 19 TRIB. TO WHARTON CREEK 30 - County 1998 08/05/2020 N 09 Otsego Burlington (Town) 3369530 3 MI N BURLINGTON FLATS COUNTY ROAD 19 TRIB WHARTON CREEK 30 - County 1998 08/05/2020 N 09 Otsego Burlington (Town) 3354100 1.2 MI N BURLINGTON FLATS COUNTY ROAD 19 WHARTON CREEK 30 - County 2004 09/09/2020 N 09 Otsego Burlington (Town) 2227350 2.75 NE OF GARRATSVILLE MILLER ROAD BUTTERNUT CREEK 40 - Town 1900 04/26/2021 N 09 Otsego Burlington (Town) 2227370 2.9 MI SE OF WEST EXETER MUNSON ROAD DUNDEE BROOK 40 - Town 1945 03/26/2021 Y 09 Otsego Butternuts (Town) 1026400 2.5 MI NE JCT SH 51 & SH 51 51 94021024 COPES BROOK NYSDOT 1968 07/15/2020 N 09 Otsego Butternuts (Town) 1026420 2 MI NE OF GILBERTSVILLE 51 51 94021069 THORP -

Surface Water Quality in Otsego County, NY, Prior to Potential Natural Gas Exploration

Surface water quality in Otsego County, NY, prior to potential natural gas exploration 1 Sarah Crosier Abstract –Baseline water quality data was established for Otsego County, NY prior to potential natural gas exploration. Hydraulic fracturing may contaminate surface water with chemicals, salts and sediments. Averages for pH, total dissolved solids, and conductivity were calculated for 50 Otsego County streams from data collected using a YSI® multi-parameter probe from August 2010 – April 2012. Limestone bedrock sub-watersheds had significantly higher conductivity, TDS and pH than shale bedrock sub-watersheds. Winter and summer peaks and fall and spring lows occurred in conductivity and TDS. Road salt use, precipitation and evaporation likely caused seasonal variation. Sub-watershed size had no significant effect on parameters. These data will serve as a control for future water quality testing if hydraulic fracturing occurs in Otsego County, NY. INTRODUCTION This study was conducted to identify baseline water quality conditions at base flow for streams in Otsego County. Water quality varies between streams due to different physical, chemical, and microbiological characteristics (Rajeshwari and Saraswathi 2009). These factors are dependent upon topography, geology, vegetative cover (Dosskey et al. 2010), land use in a watershed (Ou and Wang 2011) and watershed size (Landers et al. 2007). Stream chemistry varies naturally throughout the seasons due to changes in precipitation, evaporation, nutrient input, and biotic activity within the streams. Anthropogenic pollutants such as road salt (Jackson and Jobbágy 2005, Kaushal et al. 2005), urban storm water runoff and agricultural pesticides, nutrients, and sediments (Madden et al. 2007) also affect stream quality variably. -

Fisheries Order 210.21 Designated Trout Streams for Michigan

FISHERIES ORDER Designated Trout Streams for Michigan Order 210.21 By authority conferred on the Natural Resources Commission and the Department of Natural Resources by Part 487 of 1994 PA 451, MCL 324.48701 to 324.48740, ordered on September 10, 2020, the following section(s) of the Fisheries Order shall read effective April 1, 2021, as follows: The streams and portions of streams in the list which follows are hereby designated as trout streams: Key to Designation List: Unless otherwise described, the location description listed after the stream name indicates the downstream limit of the trout designation. All of the stream and its tributaries, unless excepted, from that point upstream are designated trout waters. Exceptions are italicized. INDEX BY GREAT LAKES BASIN Stream location Page Upper Peninsula Streams Flowing Into Lake Superior ............................................................... 1 Upper Peninsula Streams Flowing Into St. Marys River And Connecting Waters ....................... 7 Upper Peninsula Streams Flowing Into Lake Huron ................................................................... 7 Upper Peninsula Streams Flowing Into Lake Michigan ............................................................... 8 Lower Peninsula Streams Flowing Into Lake Michigan ..............................................................16 Lower Peninsula Streams Flowing Into Lake Huron ..................................................................31 Lower Peninsula Streams Flowing Into Lake St. Clair ...............................................................40 -

Baseline Surface Water Monitoring in Otsego County

Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following people and departments for their assistance in making this project possible. This research was partially funded by the Otsego County Conservation Association through Scott Fickbohm at the Otsego County Soil and Water Conservation District. Other funding came from the Departments of Chemistry, and Geology and Environmental Sciences at Hartwick College. I thank Dr. John Dudek, who assisted me with instrumentation throughout my analytical work and Dr. Zsuzsanna Balogh-Brunstad, who served as a mentor and thesis advisor for this project. ii Baseline Water Quality Monitoring in the Watersheds of Otsego County, NY by Nicole M. Daniels, B.A. Hartwick College May 2013 Advisor: Dr. Zsuzsanna Balogh-Brunstad Abstract The Marcellus Shale has become of particular interest to those interested in natural gas production using the now economically feasible hydraulic fracturing (fracking) technique. The Otsego County Soil and Water Conservation District has begun monitoring local watersheds so that a baseline for various parameters (pH, turbidity, total dissolved solid, temperature, and electrical conductivity) can be set. This way, if the Marcellus Shale in New York State is selected for natural gas extraction using hydraulic fracturing methods, the water quality can be compared to pre-gas extraction levels to insure the integrity of the water quality and ecosystem. The goal of this study was to determine the current concentrations of strontium in surface water in Otsego County, NY as it is an indicator of brine water input to freshwater ecosystems. Brines are associated with flowback and production waters of natural gas extraction after fracking operations, and thus, can indicate a mishandling of such fluids on the surface. -

Town of Hartwick

FINAL Town of Hartwick All Hazards Mitigation Plan January 2005 Amended December 2006 Prepared by: Town of Hartwick Hazard Mitigation Committee And The Otsego County Planning Department 197 Main Street Cooperstown, New York 13326 This hazards mitigation plan encompasses the Town of Hartwick, New York. This plan was developed through coordination with the Otsego County Planning Department and was funded, in part, by a Pre-Disaster Mitigation program grant from the New York State Emergency Management Office and Federal Emergency Management Agency. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Section 1 – Executive Summary 1-1 Background 1-1 Planning Process 1-1 Risk Assessment 1-1 Mitigation Strategy 1-2 Action Plan 1-3 Plan Maintenance 1-5 Section 2 - Background 2-1 Section 3 - Planning Process 3-1 Section 4 - Risk Assessment introduction 4-1 Town Historic data 4-2 HAZNY results 4-3 Hazard Definitions 4-5 Moderately High Hazards 4-7 Moderately Low Hazards 4-14 Low Hazards 4-26 Critical Building Value, Replacement and Content Cost 4-28 Critical Facilities Inventory 4-28 Damages assessment 4-30 Page Section 5 - Mitigation Goals and Actions introduction 5-1 Actions Specific to New and Existing Buildings 5-2 Prioritized method of goals and actions 5-6 Goals and Action Plan 5-7 Section 6 - Plan Maintenance 6-1 Appendix A - List of Acronyms A Appendix B - Hartwick All-Hazard Mitigation Plan Adoption B-1 – Appointment of Members to Planning Committee B-1 B-2 – Plan Adoption B-2 B-3 – Resolution of amended plan 2006 B-3 Appendix C – Notices C C-1 – Public Notice C-1 -

Exhibit C 190284

190284 Exhibit C 190284 Exhibit C- U.S.G.S. HUC 12 Watersheds that contain and/or are immediately adjoining a U.S. EPA 303(d) water body impaired by PCBs States HUC12 Name AL,GA,TN 060200011204 Lower Nickajack Lake-Tennessee River AL 031501051003 Weiss Lake-Coosa River AL 031501060203 Big Cove Creek AL 031501060204 Turkey Town Creek AL 031501060309 H. -

Gazetteer of Maryland

Bulletin No. 231 Series F, Geography, 39 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIRECTOK GAZETTEER OF MARYLAND BY HENRY. QA.NISTETT WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1904 0 tf y LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, Washington, D. C., March 9, 1904. SIR: I have the honor to transmit herewith, for publication as a bulletin, a gazetteer of Maryland. Very respectfully, HENRY GANNETT,. Geographer. Hon. CHARLES D. WALCOTT, Director United States Geological Survey. 3 A GAZETTEER OF MARYLAND. By HENRY GANNETT. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE STATE. Maryland is one of the Eastern States, bordering on the Atlantic Ocean, about midway between the northern and southern boundaries of the country. It lies between latitudes 37° 53' and 39° 44', and between longitudes 75° 04 and 79° 33'. Its neighbors are Pennsyl vania on the north, West Virginia and Virginia on the west and south, and Delaware on the east. Its north boundary is Mason and Dixon's line, and its east boundary is, in part, a nearly north-south line separating it from Delaware and Pennsylvania, and, in part, the Atlantic Ocean. On the south the boundary is an irregular line across the peninsula separating Chesapeake Bay from the Atlantic Ocean; then across Chesapeake Bay to the southern point of the entrance to Potomac River; thence following the low-water line on the south bank of the Potoniac to the head of the north branch of that river, at a point known as Fairfax Stone, excepting the area of the District of Columbia.