AC31 Doc. 41.4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universidad Nacional Autónoma De México

Instituto de Biotecnología Informe de Actividades 2014 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Cuernavaca, Morelos, México 1 Índice Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México 004 El Instituto de Biotecnología 007 Presentación 007 Antecedentes 008 Localización e Instalaciones 010 Misión y Objetivos 010 Organigrama aprobado por el CTIC 011 Organigrama a ser propuesto al CTIC 012 Acciones Estratégicas de Renovación Institucional 012 Revisión Integral de la Normatividad Interna 012 Establecimiento de la Secretaría de Vinculación (a ser ratificada al CTIC) 014 Establecimiento de la Coordinación de Infraestructura (a ser ratificada al CTIC) 016 Laboratorios de Investigación en Programas Institucionales (LInPIS´s) 018 Laboratorio de Análisis de Moleculas y Medicamentos Biotecnológicos (LAMMB) 019 Organización Académica 021 Dirección 022 Secretaría Académica 022 Secretaría de Vinculación (a ser propuesta al CTIC) 023 Coordinación de Infraestructura (a ser propuesta al CTIC) 023 Grupos de Investigación 024 Departamento de Biología Molecular de Plantas 025 Departamento de Genética del Desarrollo y Fisiología Molecular 048 Departamento de Ingeniería Celular y Biocatálisis 078 Departamento de Medicina Molecular y Bioprocesos 104 Departamento de Microbiología Molecular 129 Secretarías y Coordinaciones 151 Secretaría de Vinculación 151 Coordinación de Infraestructura 157 Unidades de Apoyo Académico 161 Unidad de Biblioteca 161 Unidad de Cómputo 163 Unidades de Apoyo Técnico 165 Unidad de Bioterio 165 Unidad de Transformación Genética y Cultivo de Tejidos -

Sustentable De Especies De Tarántula

Plan de acción de América del Norte para un comercio sustentable de especies de tarántula Comisión para la Cooperación Ambiental Citar como: CCA (2017), Plan de acción de América del Norte para un comercio sustentable de especies de tarántula, Comisión para la Cooperación Ambiental, Montreal, 48 pp. La presente publicación fue elaborada por Rick C. West y Ernest W. T. Cooper, de E. Cooper Environmental Consulting, para el Secretariado de la Comisión para la Cooperación Ambiental. La información que contiene es responsabilidad de los autores y no necesariamente refleja los puntos de vista de los gobiernos de Canadá, Estados Unidos o México. Se permite la reproducción de este material sin previa autorización, siempre y cuando se haga con absoluta precisión, su uso no tenga fines comerciales y se cite debidamente la fuente, con el correspondiente crédito a la Comisión para la Cooperación Ambiental. La CCA apreciará que se le envíe una copia de toda publicación o material que utilice este trabajo como fuente. A menos que se indique lo contrario, el presente documento está protegido mediante licencia de tipo “Reconocimiento – No comercial – Sin obra derivada”, de Creative Commons. Detalles de la publicación Categoría del documento: publicación de proyecto Fecha de publicación: mayo de 2017 Idioma original: inglés Procedimientos de revisión y aseguramiento de la calidad: Revisión final de las Partes: abril de 2017 QA311 Proyecto: Fortalecimiento de la conservación y el aprovechamiento sustentable de especies listadas en el Apéndice II de la -

Zootaxa, Megaphobema Teceae N. Sp. (Araneae, Theraphosidae)

Zootaxa 1115: 61–68 (2006) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 1115 Copyright © 2006 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Megaphobema teceae n. sp. (Araneae, Theraphosidae), a new theraphosine spider from Brazilian Amazonia FERNANDO PÉREZ-MILES1, LAURA T. MIGLIO2 & ALEXANDRE B. BONALDO2 1Seccíon Entomología, Facultad de Ciencias, Iguá 4225, 11400 Montevideo, Uruguay. E-mail: [email protected] 2Coordenação de Zoologia, Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Av. Magalhães Barata, 376, Caixa Postal 399, 66040-170, Belém, PA, Brazil. E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract A new species from Juruti River Plateau, Juruti, Pará, Brazil that fits the generic characters of Megaphobema is described. Megaphobema teceae n. sp. differs from the other four species known in this genus mainly by the presence of a conspicuous post-ocular process. This is the first record of the genus to both oriental Amazon and Brazil. Keywords: Araneae, Theraphosidae, Megaphobema, Brazilian Amazon, Neotropical, Taxonomy Introduction The genus Megaphobema Pocock 1901 comprises very large spiders from Central América (Costa Rica) and North-western South America (Colombia and Ecuador). Males are characterized by a palpal organ with a very wide concave-convex embolus with prolateral superior and inferior keels, and apical and prolateral accessory keels. The prolateral accessory keels are also present in males Sericopelma Ausserer 1875 but they can be distinguished from Megaphobema by the absence of a tibial apophysis. Females have one spermathecal receptacle transversely striated the synapomorphy of Megaphobema + Sericopelma + Theraphosa Thorell 1870. The genus has both Type I and III urticating hairs. Using these characters among others, this genus was placed in the apical portion of the cladogram of the Theraphosinae (Pérez-Miles et al. -

Artikel-Preisliste Käfer

[email protected] Artikel-Preisliste Tel.: +49 5043 98 99 747 Fax: +49 5043 98 99 749 Weitere Informationen zu unseren Produkten sowie aktuelle Angebote finden Sie in unserem Shop: www.thepetfactory.de Art.-Nr. Artikelbezeichnung Ihr Preis MwSt.-Satz * Käfer - Imagines METUFM Mecynorrhina torquata ugandensis FARBMORPHE - 79,50 € 1 PAAEMI Pachnoda aemula - Stückpreis 9,95 € 1 EUMOI Eudicella morgani - Stückpreis 14,50 € 1 PAMPI Pachnoda marginata peregrina - Stückpreis 3,95 € 1 METIM Mecynorrhina torquata immaculicollis - Stückpreis 34,50 € 1 CETSPK1 Pseudinca camerunensis - Stückpreis 14,95 € 1 PSEMAR Pseudinca marmorata 12,95 € 1 DIMIIM Dicronorhina micans - Pärchen 39,95 € 1 PASFI Pachnoda flaviventris - Stückpreis 6,95 € 1 PRFORMOI Protaetia formosana 11,95 € 1 JURUI Jumnos ruckeri 24,95 € 1 EUSPWI Eudicella schultzeorum pseudowoermanni - Stückpreis 16,95 € 1 COLORI Coelorrhina loricata Imago - Stückpreis 19,95 € 1 ANTSXMA Anthia sexmaculata - Stückpreis 19,50 € 1 PAPRASI Pachnoda prasina 29,95 € 1 PAISKUU Pachnoda iskuulka NEUE ART!!! 29,95 € 1 ZOMOIM Zophobas morio Käfer 3,95 € 1 PRPRPad Protaetia pryeri pryeri 14,95 € 1 CESPECYAAD Cetonischema speciosa cyanochlora 49,95 € 1 - 1 GRAPTRILBRSA 24,95 € 1 ORYSPECRSA Oryctes spec. RSA Paar 49,95 € 1 PASFIRSA Pachnoda flaviventris RSA WC 11,95 € 1 DISRUFRSA Dischista rufa RSA WC 14,95 € 1 PORHEBRSA Porphyronota hebreae RSA 29,95 € 1 PLAPLARSA Plaesiorrhinella plana RSA 12,50 € 1 ANTBIGUVRSA Anthia biguttata var. RSA 29,50 € 1 ANTBIGURSA Anthia biguttata RSA 29,50 € 1 CYALRSA Cypholoba alveolata RSA 44,95 € 1 ANSCULRSA Anomalipus sculpturatus RSA 24,50 € 1 ANTMAXRSA Anthia maxillosa RSA 44,95 € 1 CYPGRAPRSA Cypholoba graphipteroides RSA 22,50 € 1 TEFMEYRSA Tefflus meyerlei RSA 27,95 € 1 PLATRIVRSA Plaesiorrhinella trivittata RSA 12,50 € 1 ANELERSA Anomalipus elephas RSA 24,50 € 1 GONOTIBRSA Gonopus tibialis RSA 24,50 € 1 PSAMVIRRSA Psammodes virago TOKTOK RSA 29,95 € 1 ANSPEC1RSA Anomalipus spec. -

BMB-WRC Animal Inventory

Department of Environment and Natural Resources BIODIVERSITY MANAGEMENT BUREAU Quezon Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City INVENTORY OF LIVE ANIMALS AT THE BMB-WILDLIFE RESCUE CENTER AS OF JULY 31, 2020 SPECIES STOCK ON HAND (AS OF COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME JULY 31, 2020) MAMMALS ENDEMIC / INDIGENOUS 1. Northern luzon cloud Ploeomys pallidus 1 rat 2. Palawan bearcat Arctictis binturong 2 3. Philippine deer Rusa marianna 2 4. Philippine monkey or Macaca fascicularis 92 Long-tailed macaque 5. Philippine palm civet Paradoxurus hermaphroditus 6 EXOTIC 6. Hedgehog Atelerix frontalis 1 7. Serval cat Leptailurus serval 2 8. Sugar glider Petaurus breviceps 58 9. Tiger Panthera tigris 2 10. Vervet monkey Chlorocebus pygerythrus 1 11. White handed gibbon Hylobates lar 1 Sub-total A 168 (Mammals) AVIANS ENDEMIC / INDIGENOUS 12. Black kite Milvus migrans 1 13. Black-crowned night Nycticorax nycticorax 1 heron 14. Blue-naped parrot Tanygnathus lucionensis 4 15. Brahminy kite Haliastur indus 41 16. Changeable hawk Spizaetus cirrhatus 6 eagle 17. Crested goshawk Accipiter trivirgatus 1 18. Crested serpent eagle Spilornis cheela 24 19. Green imperial pigeon Ducula aenea 2 20. Grey-headed fish eagle Haliaeetus ichthyaetus 1 21. Nicobar pigeon Caloenas nicobarica 1 22. Palawan hornbill Anthracoceros marchei 2 23. Palawan talking myna Gracula religiosa 3 24. Philippine eagle Pithecophaga jefferyi 1 25. Philippine hanging Loriculus philippensis 11 parrot 26. Philippine hawk eagle Spizaetus philippensis 12 27. Philippine horned Bubo philippensis 9 (eagle) owl 28. Philippine Scops owl Otus megalotis 5 29. Pink-necked pigeon Treron vernans 1 30. Pinsker's hawk eagle Spizaetus pinskerii 1 31. Red turtle dove Streptopelia tranquebarica 1 32. -

A New Species of North American Tarantula , Aphonopelma Paloma (Araneae, Mygalomorphae, Theraphosidae )

1992. The Journal of Arachnology 20 :189—199 A NEW SPECIES OF NORTH AMERICAN TARANTULA , APHONOPELMA PALOMA (ARANEAE, MYGALOMORPHAE, THERAPHOSIDAE ) Thomas R. Prentice: Department of Entomology, University of California, Riverside , California 92521, US A ABSTRACT. Aphonopelma paloma new species, is distinguished from all other North American tarantula s by its unusually small size and presence of setae partially or completely dividing the scopula of tarsus IV i n both sexes. Both sexes also are characterized by a general reduction of the scopula on metatarsus IV . Males are characterized by a swollen third femur . In 1939 and 1940 R. V. Chamberlin and W. with anterior and posterior edges in the same Ivie described almost all of the currently recog- plane. All ink drawings except femora were aide d nized North American theraphosid spiders . De- by a camera lucida. Palpal bulb and seminal re- spite the acknowledged significance of their work , ceptacles were cleared in 10% NaOH (for 12 hr. it is difficult to apply Chamberlin's keys wit h at 50 °C.) prior to illustration . Scanning electron much success even in dealing with specimen s micrographs were taken with a JEOL JSM C35 . from type localities, primarily because their small Abbreviations for eyes are standard for Araneae. sample sizes did not allow variational assess- For leg spination, abbreviations are as follows : ment. Eleven of these species descriptions were a = apical, b = basal, d = dorsal, e = preapical, based on single males, five on single females, an d L = left, m = medial, p = prolateral direction, r three on two males each (Chamberlin & Ivie 1939; = retrolateral direction, R = right, usu . -

Redescription of the Holotypes of Mygalarachnae Ausserer 1871 And

ARTÍCULO: Redescription of the holotypes of Mygalarachnae Ausserer 1871 and Harpaxictis Simon (1892) (Araneae: Theraphosidae) with rebuttal of their synonymy with Sericopelma Ausserer 1875. Ray Gabriel and Stuart.J. Longhorn ARTÍCULO: Abstract: Redescription of the holotypes of The examination of specimens from various Neotropical tarantula genera (The- Mygalarachnae Ausserer 1871 and raphosidae) indicated the unique nature of monotypic genera Mygalarachnae Harpaxictis Simon (1892) (Araneae: Ausserer 1871 and Harpaxictis Simon 1892. Review of the both holotypes leads Theraphosidae) with rebuttal of their us to argue that Mygalarachnae and Harpaxictis should be removed from their synonymy with Sericopelma current synonymy with Sericopelma Ausserer 1875. The presence of type I and Ausserer 1875. III urticating hairs on the holotype specimen of Mygalarachnae firmly place it in the subfamily Theraphosinae and we argue should be restored as a valid genus, Ray Gabriel so that current placement of “incertae sedis” is inappropriate. The identity of Hope Entomological Collections, Harpaxictis striatus is less certain, but here removed from synonymy with Seri- Oxford University Museum of Natural copelma, and due to a lack of other diagnostic features is suggested as nomen History, Parks Road, Oxford, dubium. Possible affinities of Mygalarachne with other valid genera of Thera- Oxon, England, OX1 3PW, UK. phosinae are briefly discussed. Key words: Sericopelma, Tarantula. Mygalarachne brevipes, Harpaxictis striatus, Stuart.J. Longhorn Taxonomy: Mygalarachne brevipes comb. rev., Harpaxictis striatus comb. rev. Dept. of Entomology. The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London, SW7 5BD, Redescripción de los holotipos de Mygalarachnae Ausserer 1871 UK. y Harpaxictis Simon (1892) rechazando su sinonímia con Dept. of Biology. -

Spider and Scorpion Case

Spider and Scorpion case Black widow spider (Lactrodectus hesperus) Black widows are notorious spiders identified by the colored, hourglass-shaped mark on their abdomens. Several species answer to the name, and they are found in temperate regions around the world. This spider's bite is much feared because its venom is reported to be 15 times stronger than a rattlesnake's. In humans, bites produce muscle aches, nausea, and a paralysis of the diaphragm that can make breathing difficult; however, contrary to popular belief, most people who are bitten suffer no serious damage—let alone death. But bites can be fatal—usually to small children, the elderly, or the infirm. Fortunately, fatalities are fairly rare; the spiders are nonaggressive and bite only in self-defense, such as when someone accidentally sits on them. These spiders spin large webs in which females suspend a cocoon with hundreds of eggs. Spiderlings disperse soon after they leave their eggs, but the web remains. Black widow spiders also use their webs to ensnare their prey, which consists of flies, mosquitoes, grasshoppers, beetles, and caterpillars. Black widows are comb- footed spiders, which means they have bristles on their hind legs that they use to cover their prey with silk once it has been trapped. To feed, black widows puncture their insect prey with their fangs and administer digestive enzymes to the corpses. By using these enzymes, and their gnashing fangs, the spiders liquefy their prey's bodies and suck up the resulting fluid. Giant desert hairy scorpion (Hadrurus arizonensis) Hadrurus arizonensis is distributed throughout the Sonora and Mojave deserts. -

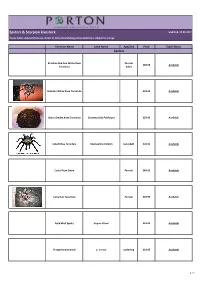

Spiders & Scorpion Livestock

Spiders & Scorpion Livestock Updated: 22.09.2017 Please Note: Livestock lists are correct at time of publishing and availability is subject to change Common Name Latin Name Age/Size Price Stock Status Spiders Brazilian Red And White Knee Female £49.95 Available Tarantula Adult Brazilian White Knee Tarantula £34.95 Available Chaco Golden Knee Tarantula Grammostola Pulchripes £29.95 Available Cobalt Blue Tarantula Haplopelma Lividum Sub Adult £49.95 Available Costa Rican Zebra Female £49.95 Available Curly Hair Tarantula Female £29.95 Available Field Wolf Spider Hogna Miami £19.95 Available Fringed Ornamental p. ornata spiderling £24.95 Available 1 / 4 Common Name Latin Name Age/Size Price Stock Status Spiders Golden Baboon Tarantula Augacephalus ezendami £39.95 Available Gooty Ornamental p. metallica spiderling £49.95 Available Green Bottle Blue Tarantula Female £49.95 Available Green Femur Birdeater Phormictopus"Green Femur" £39.95 Available Indian Ornamental Tarantula Poecilotheria regalis 2cm £24.95 Available King Baboon Tarantula Pelinobius Muticus £24.95 Available Martinique Pink Toe Tarantula 2cm £16.95 Available Mexican Fire Leg Tarantula Brachypelma Bohemi £39.95 Available Mexican Red Knee Tarantula Brachypelma Smithi £34.95 Available 2 / 4 Common Name Latin Name Age/Size Price Stock Status Spiders Mexican Red Leg Tarantula Brachypelma Emilia £39.95 Available £24.95 Available Mexican Red Rump Brachypelma Vagans Female Sub Adult Available £49.95 spiderling £19.95 Available OBT Tarantula Female Sub Adult Available £39.95 Purple Earth -

Genetic Analysis of Tarantulas in the Genus Brachypelma Using Inter Simple Sequence Repeats (ISSR)

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses & Projects Honors College 2020 Genetic analysis of tarantulas in the genus Brachypelma using Inter Simple Sequence Repeats (ISSR) Sarah Holtzen Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.emich.edu/honors Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Holtzen, Sarah, "Genetic analysis of tarantulas in the genus Brachypelma using Inter Simple Sequence Repeats (ISSR)" (2020). Senior Honors Theses & Projects. 688. https://commons.emich.edu/honors/688 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses & Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Genetic analysis of tarantulas in the genus Brachypelma using Inter Simple Sequence Repeats (ISSR) Abstract There is a great deal of morphological and genetic species diversity on Earth that requires careful conservation. One such genetically diverse genus of tarantulas is that of Brachypelma. In this study, we employ a newer DNA fingerprinting technique known as Inter Simple Sequence Repeat (ISSR), ot study the genetic variation among Brachypelma species and to determine if the invasive Brachypelma tarantula found in Florida B. vagans. Although B. vagans is a species protected under CITES Appendix II, this species has a wide distribution in Mexico and traits allowing for invasion to new habitats. It was hypothesized that the invasive tarantula in Florida is that of B. vagans and that it would be more closely related to samples from the Mexican populations as opposed to samples from the United States pet trade. -

Colorado Tarantulas

Colorado Arachnids of Interest Colorado Tarantulas Scientific Name: Aphonopelma spp. (3-5 species) Class: Arachnida (Arachnids) Order: Araneae (Spiders) Family: Theraphosidae (Tarantulas) Figure 1. Male Oklahoma brown tarantula (Aphonopelma hentzi) crossing road. Identification and Descriptive Features: Tarantulas (Figures 1, 2, 3 and 6) are large, hairy spiders and all species found in Colorado are generally dark brown to black. Longer hairs are usually present on the abdomen and these may be a lighter brown color. Some banding of colors may be present on the legs. The carapace (back of the section with legs and head/cephalothorax) of eastern Colorado species ranges from light gray-brown to dark reddish brown with some coppery tones. Almost all tarantulas that are observed are mature males migrating in late summer and early fall. Females (Figure 2), which are much less commonly collected and observed than the adult males, will be found within the very near vicinity of their burrows. They usually have similar markings to the males but do not develop the very long legs of mature males. Adult females are also considerably larger than the Figure 2. Tarantula female emerging from males. For example, the carapace length of A. hentzi burrow. Otero County. may be about 20 mm in the female and only about 15 mm in the male. Two “mini-tarantulas” are known from western Colorado. Most common is Aphonopelma vogelae Smith (Figure 3). County records for this species include Montezuma, Montrose, and San Miguel. Males have a carapace length of about 10 mm. The western Colorado species tend to be more uniformly dark brown to black than those in southeastern Colorado. -

A Guide to Arthropods Bandelier National Monument

A Guide to Arthropods Bandelier National Monument Top left: Melanoplus akinus Top right: Vanessa cardui Bottom left: Elodes sp. Bottom right: Wolf Spider (Family Lycosidae) by David Lightfoot Compiled by Theresa Murphy Nov 2012 In collaboration with Collin Haffey, Craig Allen, David Lightfoot, Sandra Brantley and Kay Beeley WHAT ARE ARTHROPODS? And why are they important? What’s the difference between Arthropods and Insects? Most of this guide is comprised of insects. These are animals that have three body segments- head, thorax, and abdomen, three pairs of legs, and usually have wings, although there are several wingless forms of insects. Insects are of the Class Insecta and they make up the largest class of the phylum called Arthropoda (arthropods). However, the phylum Arthopoda includes other groups as well including Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, shrimps, barnacles, etc.), Myriapoda (millipedes, centipedes, etc.) and Arachnida (scorpions, king crabs, spiders, mites, ticks, etc.). Arthropods including insects and all other animals in this phylum are characterized as animals with a tough outer exoskeleton or body-shell and flexible jointed limbs that allow the animal to move. Although this guide is comprised mostly of insects, some members of the Myriapoda and Arachnida can also be found here. Remember they are all arthropods but only some of them are true ‘insects’. Entomologist - A scientist who focuses on the study of insects! What’s bugging entomologists? Although we tend to call all insects ‘bugs’ according to entomology a ‘true bug’ must be of the Order Hemiptera. So what exactly makes an insect a bug? Insects in the order Hemiptera have sucking, beak-like mouthparts, which are tucked under their “chin” when Metallic Green Bee (Agapostemon sp.) not in use.