Lutra Lutra) and Potential Applications for Population Monitoring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VOLATILE COMPOUNDS from ANAL GLANDS of the WOLVERINE, Gulo Gulo

Journal of Chemical Ecology, Vol. 12, No. 9, September 2005 ( #2005) DOI: 10.1007/s10886-005-6080-9 VOLATILE COMPOUNDS FROM ANAL GLANDS OF THE WOLVERINE, Gulo gulo WILLIAM F. WOOD,1,* MIRANDA N. TERWILLIGER,2 and JEFFREY P. COPELAND3 1Department of Chemistry, Humboldt State University, Arcata, CA 95521, USA 2Alaska Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Unit, Department of Biology & Wildlife, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA 3USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Missoula, MT 59801, USA (Received February 12, 2005; revised March 24, 2005; accepted April 20, 2005) Abstract—Dichloromethane extracts of wolverine (Gulo gulo, Mustelinae, Mustelidae) anal gland secretion were examined by gas chromatographyYmass spectrometry. The secretion composition was complex and variable for the six samples examined: 123 compounds were detected in total, with the number per animal ranging from 45 to 71 compounds. Only six compounds were common to all extracts: 3-methylbutanoic acid, 2-methylbutanoic acid, phenylacetic acid, a-tocopherol, cholesterol, and a compound tentatively identified as 2-methyldecanoic acid. The highly odoriferous thietanes and dithiolanes found in anal gland secretions of some members of the Mustelinae [ferrets, mink, stoats, and weasels (Mustela spp.) and zorillas (Ictonyx spp.)] were not observed. The composition of the wolverine’s anal gland secretion is similar to that of two other members of the Mustelinae, the pine and beech marten (Martes spp.). Key WordsVWolverine, Gulo gulo, Mustelinae, Mustelidae, scent marking, fear-defense mechanism, short-chain carboxylic acids. INTRODUCTION The wolverine (Gulo gulo) is the largest terrestrial member of the Mustelidae and is part of the subfamily, Mustelinae, which includes ferrets, fishers, martens, mink, stoats, weasels, and zorillas. -

Otter News No. 124, July 2021

www.otter.org IOSF Otter News No. 124, July 2021 www.loveotters.org Otter News No. 124, July 2021 Join our IOSF mailing list and receive our newsletters - Click on this link: http://tinyurl.com/p3lrsmx Please share our news Good News for Otters in Argentina Giant otters are classified as “extinct” in Argentina but there have been some positive signs of their return in recent months. The Ibera wetlands lie in the Corrientes region and are one of the world’s largest freshwater ecosystems. Rewilding Argentina is attempting to return the country’s rich biodiversity to the area with species such as jaguars, macaws and marsh deer. They have also been working to bring back giant otters and there have been some small successes and three cubs have recently been born as offspring of two otters that were reintroduced there. And there is more good news for the largest otter species. In May there was the first sighting of “wild” giant otters in Argentina for 40 years! Furthermore, there have been other success stories for otters across the south American nation. Tierra del Fuego, Argentina’s southern-most province, has banned all open-net salmon farming. This ban will help protect the areas fragile marine ecosystems, which is home to half of Argentina’s kelp forests which support species such as the southern river otter. This also makes Argentina the first nation in the world to ban such farming practices. With so many problems for otter species it is encouraging to see some steps forward in their protection in Argentina. -

Monitoring Wolverines in Northeast Oregon

Monitoring Wolverines in Northeast Oregon January 2011 – December 2012 Final Report Authors: Audrey J. Magoun Patrick Valkenburg Clinton D. Long Judy K. Long Submitted to: The Wolverine Foundation, Inc. February 2013 Cite as: A. J. Magoun, P. Valkenburg, C. D. Long, and J. K. Long. 2013. Monitoring wolverines in northeast Oregon. January 2011 – December 2012. Final Report. The Wolverine Foundation, Inc., Kuna, Idaho. [http://wolverinefoundation.org/] Copies of this report are available from: The Wolverine Foundation, Inc. [http://wolverinefoundation.org/] Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife [http://www.dfw.state.or.us/conservationstrategy/publications.asp] Oregon Wildlife Heritage Foundation [http://www.owhf.org/] U. S. Forest Service [http://www.fs.usda.gov/land/wallowa-whitman/landmanagement] Major Funding and Logistical Support The Wolverine Foundation, Inc. Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Oregon Wildlife Heritage Foundation U. S. Forest Service U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Wolverine Discovery Center Norcross Wildlife Foundation Seattle Foundation Wildlife Conservation Society National Park Service 2 Special thanks to everyone who provided contributions, assistance, and observations of wolverines in the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest and other areas in Oregon. We appreciate all the help and interest of the staffs of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Oregon Wildlife Heritage Foundation, U. S. Forest Service, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Wildlife Conservation Society, and the National Park Service. We also thank the following individuals for their assistance with the field work: Jim Akenson, Holly Akenson, Malin Aronsson, Norma Biggar, Ken Bronec, Steve Bronson, Roblyn Brown, Vic Coggins, Alex Coutant, Cliff Crego, Leonard Erickson, Bjorn Hansen, Mike Hansen, Hans Hayden, Tim Hiller, Janet Hohmann, Pat Matthews, David McCullough, Glenn McDonald, Jamie McFadden, Kendrick Moholt, Mark Penninger, Jens Persson, Lynne Price, Brian Ratliff, Jamie Ratliff, John Stephenson, John Wyanens, Rebecca Watters, Russ Westlake, and Jeff Yanke. -

Post Mortem and Genetic Study of an Eurasian Otter (Lutra Lutra) Carcass Collected in Hong Kong SAR

Post mortem and genetic study of an Eurasian Otter (Lutra lutra) carcass collected in Hong Kong SAR China Published: October 2018 Kadoorie Farm & Botanic Garden Publication Series No.16 Post mortem and genetic study of an Eurasian Otter (Lutra Lutra) carcass collected in Hong Kong SAR Post mortem and genetic study of an Eurasian Otter (Lutra lutra) carcass collected in Hong Kong SAR, China October 2018 Authors and Editorial Miss. Wing Lam Fok Dr. Gary W.J. Ades Mr. Paul Crow Dr. Huarong Zhang Dr. Alessandro Grioni Mr. Yu Ki Wong Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 Section 1: Post Mortem Examination ........................................................................................ 4 Section 2: Genetic analysis confirmed taxonomic identity of the otter .................................... 8 Conclusions ................................................................................................................................ 9 Implication of the dog attack and recommendations for L. lutra conservation ....................... 9 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. 10 References ............................................................................................................................... 10 Further Readings ..................................................................................................................... -

Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Anorectal Abscess, Fistula-In-Ano, and Rectovaginal Fistula Jon D

PRACTICE GUIDELINES Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Anorectal Abscess, Fistula-in-Ano, and Rectovaginal Fistula Jon D. Vogel, M.D. • Eric K. Johnson, M.D. • Arden M. Morris, M.D. • Ian M. Paquette, M.D. Theodore J. Saclarides, M.D. • Daniel L. Feingold, M.D. • Scott R. Steele, M.D. Prepared on behalf of The Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons he American Society of Colon and Rectal Sur- and submucosal locations.7–11 Anorectal abscess occurs geons is dedicated to ensuring high-quality pa- more often in males than females, and may occur at any Ttient care by advancing the science, prevention, age, with peak incidence among 20 to 40 year olds.4,8–12 and management of disorders and diseases of the co- In general, the abscess is treated with prompt incision lon, rectum, and anus. The Clinical Practice Guide- and drainage.4,6,10,13 lines Committee is charged with leading international Fistula-in-ano is a tract that connects the perine- efforts in defining quality care for conditions related al skin to the anal canal. In patients with an anorec- to the colon, rectum, and anus by developing clinical tal abscess, 30% to 70% present with a concomitant practice guidelines based on the best available evidence. fistula-in-ano, and, in those who do not, one-third will These guidelines are inclusive, not prescriptive, and are be diagnosed with a fistula in the months to years after intended for the use of all practitioners, health care abscess drainage.2,5,8–10,13–16 Although a perianal abscess workers, and patients who desire information about the is defined by the anatomic space in which it forms, a management of the conditions addressed by the topics fistula-in-ano is classified in terms of its relationship to covered in these guidelines. -

Coyote Canis Latrans in 2007 IUCN Red List (Canis Latrans)

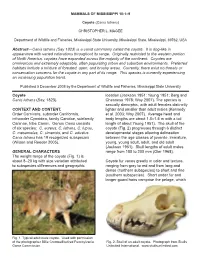

MAMMALS OF MISSISSIPPI 10:1–9 Coyote (Canis latrans) CHRISTOPHER L. MAGEE Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, Mississippi, 39762, USA Abstract—Canis latrans (Say 1823) is a canid commonly called the coyote. It is dog-like in appearance with varied colorations throughout its range. Originally restricted to the western portion of North America, coyotes have expanded across the majority of the continent. Coyotes are omnivorous and extremely adaptable, often populating urban and suburban environments. Preferred habitats include a mixture of forested, open, and brushy areas. Currently, there exist no threats or conservation concerns for the coyote in any part of its range. This species is currently experiencing an increasing population trend. Published 5 December 2008 by the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Mississippi State University Coyote location (Jackson 1951; Young 1951; Berg and Canis latrans (Say, 1823) Chesness 1978; Way 2007). The species is sexually dimorphic, with adult females distinctly CONTEXT AND CONTENT. lighter and smaller than adult males (Kennedy Order Carnivora, suborder Caniformia, et al. 2003; Way 2007). Average head and infraorder Cynoidea, family Canidae, subfamily body lengths are about 1.0–1.5 m with a tail Caninae, tribe Canini. Genus Canis consists length of about Young 1951). The skull of the of six species: C. aureus, C. latrans, C. lupus, coyote (Fig. 2) progresses through 6 distinct C. mesomelas, C. simensis, and C. adustus. developmental stages allowing delineation Canis latrans has 19 recognized subspecies between the age classes of juvenile, immature, (Wilson and Reeder 2005). young, young adult, adult, and old adult (Jackson 1951). -

Abstract Book

EAZA NUTRITION GROUP & ZOOLOGICKÁ ZAHRADA LIBEREC ABSTRACT BOOK Editors Liberec Zoological Garden Marcus Clauss Lidové sady 425/1 Anouk Fens 460 01 Liberec 1 Joeke Nijboer Czech Republic Foreword Dear friends and colleagues, Time flies! After the first European Zoo Nutrition Conference in Rotterdam, in 1999, we are happy to present you the 9th European Zoo Nutrition Conference in Liberec, the Czech Republic. The European Nutrition Group (ENG) has proven to be an active group within EAZA. Certainly, it means that the animals in the European zoos will benefit from the improved diets as a result of presentations, posters, workshops and discussions held at the conferences and by the other activities organised by the ENG. One of the promoters of the ENG, Andrea Fidgett, resigned after chairing the group for more than 10 years, as she accepted a position in the USA. Ollie Szyszka, nutritionist in Marwell Zoo, will be the new chair and intends to stimulate and promote zoo animal nutrition within the ENG and European zoo community. The organising committee is pleased to present you a wide range of talks and posters, varying from sustainable palm oil, rhinoceros feeding, contraception by feeding, dietary drift, fertility in birds, milk composition, insects as feed for zoo animals to pest control in zoos. Prior to the conference, the EAZA Academy in cooperation with ENG, organises a workshop on January 26th titled: pellet formulation. After the success of the practical workstations during the last conference in Arnhem Zoo, we will have several workstation again during the zoo visit on Saturday, where information will be presented on specific zoo animal nutrition items during. -

The 2008 IUCN Red Listings of the World's Small Carnivores

The 2008 IUCN red listings of the world’s small carnivores Jan SCHIPPER¹*, Michael HOFFMANN¹, J. W. DUCKWORTH² and James CONROY³ Abstract The global conservation status of all the world’s mammals was assessed for the 2008 IUCN Red List. Of the 165 species of small carni- vores recognised during the process, two are Extinct (EX), one is Critically Endangered (CR), ten are Endangered (EN), 22 Vulnerable (VU), ten Near Threatened (NT), 15 Data Deficient (DD) and 105 Least Concern. Thus, 22% of the species for which a category was assigned other than DD were assessed as threatened (i.e. CR, EN or VU), as against 25% for mammals as a whole. Among otters, seven (58%) of the 12 species for which a category was assigned were identified as threatened. This reflects their attachment to rivers and other waterbodies, and heavy trade-driven hunting. The IUCN Red List species accounts are living documents to be updated annually, and further information to refine listings is welcome. Keywords: conservation status, Critically Endangered, Data Deficient, Endangered, Extinct, global threat listing, Least Concern, Near Threatened, Vulnerable Introduction dae (skunks and stink-badgers; 12), Mustelidae (weasels, martens, otters, badgers and allies; 59), Nandiniidae (African Palm-civet The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is the most authorita- Nandinia binotata; one), Prionodontidae ([Asian] linsangs; two), tive resource currently available on the conservation status of the Procyonidae (raccoons, coatis and allies; 14), and Viverridae (civ- world’s biodiversity. In recent years, the overall number of spe- ets, including oyans [= ‘African linsangs’]; 33). The data reported cies included on the IUCN Red List has grown rapidly, largely as on herein are freely and publicly available via the 2008 IUCN Red a result of ongoing global assessment initiatives that have helped List website (www.iucnredlist.org/mammals). -

Exploiting Interspecific Olfactory Communication to Monitor Predators

Ecological Applications, 27(2), 2017, pp. 389–402 © 2016 by the Ecological Society of America Exploiting interspecific olfactory communication to monitor predators PATRICK M. GARVEY,1,2 ALISTAIR S. GLEN,2 MICK N. CLOUT,1 SARAH V. WYSE,1,3 MARGARET NICHOLS,4 AND ROGER P. PECH5 1Centre for Biodiversity and Biosecurity, School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand 2Landcare Research, Private Bag 92170, Auckland, 1142 New Zealand 3Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, Wakehurst Place, RH17 6TN United Kingdom 4Centre for Wildlife Management and Conservation, Lincoln University, Canterbury, New Zealand 5Landcare Research, PO Box 69040, Lincoln, 7640 New Zealand Abstract. Olfaction is the primary sense of many mammals and subordinate predators use this sense to detect dominant species, thereby reducing the risk of an encounter and facilitating coexistence. Chemical signals can act as repellents or attractants and may therefore have applications for wildlife management. We devised a field experiment to investigate whether dominant predator (ferret Mustela furo) body odor would alter the behavior of three common mesopredators: stoats (Mustela erminea), hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus), and ship rats (Rattus rattus). We predicted that apex predator odor would lead to increased detections, and our results support this hypothesis as predator kairomones (interspecific olfactory messages that benefit the receiver) provoked “eavesdropping” behavior by mesopredators. Stoats exhib- ited the most pronounced responses, with kairomones significantly increasing the number of observations and the time spent at a site, so that their occupancy estimates changed from rare to widespread. Behavioral responses to predator odors can therefore be exploited for conserva- tion and this avenue of research has not yet been extensively explored. -

Ecology of Free-Living Cats Exploiting Waste Disposal Sites

0 ECOLOGY OF FREE-LIVING CATS EXPLOITING WASTE DISPOSAL SITES DIET, MORPHOMETRICS, POPULATION DYNAMICS AND POPULATION GENETICS ELIZABETH ANN DENNY B.A. M.Litt. A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School ofBiological Sciences U ni versity of Sydney 2005 CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINALITY I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no material previously published or written by another person, nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at the University of Sydney or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at the University of Sydney or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. ~:- Elizabeth Ann Denny November, 2005 ABSTRACT The free-living domestic cat (Felis catus), a feral predator in Australia, occupies the entire continent and many offshore islands. Throughout the Australian landscape are rubbish tips, which provide biological attraction points around which free-living cats congregate in high densities. This study examined populations of cats exploiting tip sites in two contrasting bioregions in New South Wales. The study determined the most useful methods for the detection and assessment of abundance of free-living cats, and compared the efficacy of the detection methods between contrasting environments. -

Small Carnivores of Karnataka: Distribution and Sight Records1

Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 104 (2), May-Aug 2007 155-162 SMALL CARNIVORES OF KARNATAKA SMALL CARNIVORES OF KARNATAKA: DISTRIBUTION AND SIGHT RECORDS1 H.N. KUMARA2,3 AND MEWA SINGH2,4 1Accepted November 2006 2 Biopsychology Laboratory, University of Mysore, Mysore 570 006, Karnataka, India. 3Email: [email protected] 4Email: [email protected] During a study from November 2001 to July 2004 on ecology and status of wild mammals in Karnataka, we sighted 143 animals belonging to 11 species of small carnivores of about 17 species that are expected to occur in the state of Karnataka. The sighted species included Leopard Cat, Rustyspotted Cat, Jungle Cat, Small Indian Civet, Asian Palm Civet, Brown Palm Civet, Common Mongoose, Ruddy Mongoose, Stripe-necked Mongoose and unidentified species of Otters. Malabar Civet, Fishing Cat, Brown Mongoose, Nilgiri Marten, and Ratel were not sighted during this study. The Western Ghats alone account for thirteen species of small carnivores of which six are endemic. The sighting of Rustyspotted Cat is the first report from Karnataka. Habitat loss and hunting are the major threats for the small carnivore survival in nature. The Small Indian Civet is exploited for commercial purpose. Hunting technique varies from guns to specially devised traps, and hunting of all the small carnivore species is common in the State. Key words: Felidae, Viverridae, Herpestidae, Mustelidae, Karnataka, threats INTRODUCTION (Mukherjee 1989; Mudappa 2001; Rajamani et al. 2003; Mukherjee et al. 2004). Other than these studies, most of the Mammals of the families Felidae, Viverridae, information on these animals comes from anecdotes or sight Herpestidae, Mustelidae and Procyonidae are generally records, which no doubt, have significantly contributed in called small carnivores. -

In the Mood Deer Have a Way of Advertising Their Wares and the Whereabouts– Scent, Sounds, and Body Language

A buck simulates reproductive response with flehman or lip curling to expose his vomeronasal organ to scent of a female’s urination. (frame from Quality Deer Management Assoc. video) In the Mood Deer have a way of advertising their wares and the whereabouts– scent, sounds, and body language J. Morton Galetto, CU Maurice River Last October I wrote an article about deer that included some aspects of their mating habits. It described mate guarding and the male deer or buck’s propensity to focus on following a female in estrus so as to insure he is the lucky suitor. During rut or the breeding season, when males spar competitively for reproductive rights over females, deer are on the move. The season begins in October and its height in our region is November 10- 20. Females that are not successfully fertilized will come into estrus a second time 28 days later, offering a second chance for them to produce young. All this moving around makes deer and drivers especially prone to road collisions. Bucks are particularly active during sunset and early morning. So slow down and stay alert. In last year’s story we offered lots of advice in this regard. White-tail deer are the local species here in Southern NJ. I thought it might be fun to talk about their indicators of lust – well, fun for me anyway. Deer employ three major methods of communications: scents, vocalizations, and body language. Deer are ungulates, meaning they are a mammal with a cloven hoof on each leg, split in two parts; you could describe them as toes or digits.