Exploiting Interspecific Olfactory Communication to Monitor Predators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carnivores of Syria 229 Doi: 10.3897/Zookeys.31.170 RESEARCH ARTICLE Launched to Accelerate Biodiversity Research

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 31: 229–252 (2009) Carnivores of Syria 229 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.31.170 RESEARCH ARTICLE www.pensoftonline.net/zookeys Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Carnivores of Syria Marco Masseti Department of Evolutionistic Biology “Leo Pardi” of the University of Florence, Italy Corresponding author: Marco Masseti (marco.masseti@unifi .it) Academic editors: E. Neubert, Z. Amr | Received 14 April 2009 | Accepted 29 July 2009 | Published 28 December 2009 Citation: Masseti, M (2009) Carnivores of Syria. In: Neubert E, Amr Z, Taiti S, Gümüs B (Eds) Animal Biodiversity in the Middle East. Proceedings of the First Middle Eastern Biodiversity Congress, Aqaba, Jordan, 20–23 October 2008. ZooKeys 31: 229–252. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.31.170 Abstract Th e aim of this research is to outline the local occurrence and recent distribution of carnivores in Syria (Syrian Arab Republic) in order to off er a starting point for future studies. The species of large dimensions, such as the Asiatic lion, the Caspian tiger, the Asiatic cheetah, and the Syrian brown bear, became extinct in historical times, the last leopard being reputed to have been killed in 1963 on the Alauwit Mountains (Al Nusyriain Mountains). Th e checklist of the extant Syrian carnivores amounts to 15 species, which are essentially referable to 4 canids, 5 mustelids, 4 felids – the sand cat having been reported only recently for the fi rst time – one hyaenid, and one herpestid. Th e occurrence of the Blandford fox has yet to be con- fi rmed. Th is paper is almost entirely the result of a series of fi eld surveys carried out by the author mainly between 1989 and 1995, integrated by data from several subsequent reports and sightings by other authors. -

Mammals of Jordan

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mammals of Jordan Z. AMR, M. ABU BAKER & L. RIFAI Abstract: A total of 78 species of mammals belonging to seven orders (Insectivora, Chiroptera, Carni- vora, Hyracoidea, Artiodactyla, Lagomorpha and Rodentia) have been recorded from Jordan. Bats and rodents represent the highest diversity of recorded species. Notes on systematics and ecology for the re- corded species were given. Key words: Mammals, Jordan, ecology, systematics, zoogeography, arid environment. Introduction In this account we list the surviving mammals of Jordan, including some reintro- The mammalian diversity of Jordan is duced species. remarkable considering its location at the meeting point of three different faunal ele- Table 1: Summary to the mammalian taxa occurring ments; the African, Oriental and Palaearc- in Jordan tic. This diversity is a combination of these Order No. of Families No. of Species elements in addition to the occurrence of Insectivora 2 5 few endemic forms. Jordan's location result- Chiroptera 8 24 ed in a huge faunal diversity compared to Carnivora 5 16 the surrounding countries. It shelters a huge Hyracoidea >1 1 assembly of mammals of different zoogeo- Artiodactyla 2 5 graphical affinities. Most remarkably, Jordan Lagomorpha 1 1 represents biogeographic boundaries for the Rodentia 7 26 extreme distribution limit of several African Total 26 78 (e.g. Procavia capensis and Rousettus aegypti- acus) and Palaearctic mammals (e. g. Eri- Order Insectivora naceus concolor, Sciurus anomalus, Apodemus Order Insectivora contains the most mystacinus, Lutra lutra and Meles meles). primitive placental mammals. A pointed snout and a small brain case characterises Our knowledge on the diversity and members of this order. -

The Status and Distribution of Mediterranean Mammals

THE STATUS AND DISTRIBUTION OF MEDITERRANEAN MAMMALS Compiled by Helen J. Temple and Annabelle Cuttelod AN E AN R R E IT MED The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ – Regional Assessment THE STATUS AND DISTRIBUTION OF MEDITERRANEAN MAMMALS Compiled by Helen J. Temple and Annabelle Cuttelod The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ – Regional Assessment The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or other participating organizations, concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or other participating organizations. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK Copyright: © 2009 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Red List logo: © 2008 Citation: Temple, H.J. and Cuttelod, A. (Compilers). 2009. The Status and Distribution of Mediterranean Mammals. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK : IUCN. vii+32pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1163-8 Cover design: Cambridge Publishers Cover photo: Iberian lynx Lynx pardinus © Antonio Rivas/P. Ex-situ Lince Ibérico All photographs used in this publication remain the property of the original copyright holder (see individual captions for details). -

Kairomones – Important Substances in Interspecific Communication in Vertebrates: a Review

Veterinarni Medicina, 58, 2013 (11): 561–566 Review Article Kairomones – important substances in interspecific communication in vertebrates: a review J. Rajchard Faculty of Agriculture, University of South Bohemia, Ceske Budejovice, Czech Republic ABSTRACT: Interspecies chemical communication is widespread among many groups of organisms, including vertebrates. Kairomones belong to a group of intensively researched substances, represent means for interspecific chemical communication in animals and bring benefit to the acceptor of the chemical signal. Important and often studied is the chemical communication between hosts and their ectoparasites such as ticks and other parasitic mite species. Uric acid is a host stimulus of the kairomone type, which is a product of bird metabolism, or secretions of blood-fed (ingested) ticks. Secretion of volatile substances with kairomone effect may depend on the health of the host organism. Another examined group is the haematophagous ectoparasite insects of the order Diptera, where in addition to the attractiveness of CO2 a number of other attractants have been described. Specificity of substances in chemical communication can also be determined by their enantiomers. Detailed study of the biology of these ectoparasites is very important from a practical point of view: these parasites play an important role as vectors in a number of infectious diseases. Another area of interspecific chemical communication is the predator-prey relationship, or rather the ability to detect the proximity of predator and induce anti-predator behaviour in the prey. This relationship has been demonstrated in aquatic vertebrates (otter Lutra lutra – salmon Salmo salar) as well as in rodents and their predators. The substances produced by carnivores that induce behavioural response in mice have already been identified. -

Controlled Animals

Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Policy Division Controlled Animals Wildlife Regulation, Schedule 5, Part 1-4: Controlled Animals Subject to the Wildlife Act, a person must not be in possession of a wildlife or controlled animal unless authorized by a permit to do so, the animal was lawfully acquired, was lawfully exported from a jurisdiction outside of Alberta and was lawfully imported into Alberta. NOTES: 1 Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column. 2 Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule. 3 This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal. Part 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 1. AMERICAN OPOSSUMS (Family Didelphidae) Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana 2. SHREWS (Family Soricidae) Long-tailed Shrews Genus Sorex Arboreal Brown-toothed Shrew Episoriculus macrurus North American Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Old World Water Shrews Genus Neomys Ussuri White-toothed Shrew Crocidura lasiura Greater White-toothed Shrew Crocidura russula Siberian Shrew Crocidura sibirica Piebald Shrew Diplomesodon pulchellum 3. -

Ecology of Red Deer a Research Review Relevant to Their Management in Scotland

Ecologyof RedDeer A researchreview relevant to theirmanagement in Scotland Instituteof TerrestrialEcology Natural EnvironmentResearch Council á á á á á Natural Environment Research Council Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Ecology of Red Deer A research review relevant to their management in Scotland Brian Mitchell, Brian W. Staines and David Welch Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Banchory iv Printed in England by Graphic Art (Cambridge) Ltd. ©Copyright 1977 Published in 1977 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology 68 Hills Road Cambridge CB2 11LA ISBN 0 904282 090 Authors' address: Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Hill of Brathens Glassel, Banchory Kincardineshire AB3 4BY Telephone 033 02 3434. The Institute of Terrestrial Ecology (ITE) was established in 1973, from the former Nature Conservancy's research stations and staff, joined later by the Institute of Tree Biology and the Culture Centre of Algae and Protozoa. ITE contributes to and draws upon the collective knowledge of the fourteen sister institutes which make up the Natural Environment Research Council, spanning all the environmental sciences. The Institute studies the factors determining the structure, composition and processes of land and freshwater systems, and of individual plant and animal species. It is developing a Sounder scientific basis for predicting and modelling environmental trends arising from natural or man-made change. The results of this research are available to those responsible for the protection, management and wise use of our natural resources. Nearly half of ITE'Swork is research commissioned by customers, such as the Nature Conservancy Council who require information for wildlife conservation, the Forestry Commission and the Department of the Environment. The remainder is fundamental research supported by NERC. -

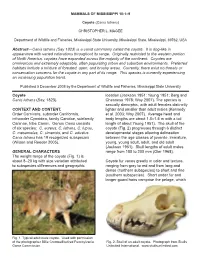

Coyote Canis Latrans in 2007 IUCN Red List (Canis Latrans)

MAMMALS OF MISSISSIPPI 10:1–9 Coyote (Canis latrans) CHRISTOPHER L. MAGEE Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, Mississippi, 39762, USA Abstract—Canis latrans (Say 1823) is a canid commonly called the coyote. It is dog-like in appearance with varied colorations throughout its range. Originally restricted to the western portion of North America, coyotes have expanded across the majority of the continent. Coyotes are omnivorous and extremely adaptable, often populating urban and suburban environments. Preferred habitats include a mixture of forested, open, and brushy areas. Currently, there exist no threats or conservation concerns for the coyote in any part of its range. This species is currently experiencing an increasing population trend. Published 5 December 2008 by the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Mississippi State University Coyote location (Jackson 1951; Young 1951; Berg and Canis latrans (Say, 1823) Chesness 1978; Way 2007). The species is sexually dimorphic, with adult females distinctly CONTEXT AND CONTENT. lighter and smaller than adult males (Kennedy Order Carnivora, suborder Caniformia, et al. 2003; Way 2007). Average head and infraorder Cynoidea, family Canidae, subfamily body lengths are about 1.0–1.5 m with a tail Caninae, tribe Canini. Genus Canis consists length of about Young 1951). The skull of the of six species: C. aureus, C. latrans, C. lupus, coyote (Fig. 2) progresses through 6 distinct C. mesomelas, C. simensis, and C. adustus. developmental stages allowing delineation Canis latrans has 19 recognized subspecies between the age classes of juvenile, immature, (Wilson and Reeder 2005). young, young adult, adult, and old adult (Jackson 1951). -

The 2008 IUCN Red Listings of the World's Small Carnivores

The 2008 IUCN red listings of the world’s small carnivores Jan SCHIPPER¹*, Michael HOFFMANN¹, J. W. DUCKWORTH² and James CONROY³ Abstract The global conservation status of all the world’s mammals was assessed for the 2008 IUCN Red List. Of the 165 species of small carni- vores recognised during the process, two are Extinct (EX), one is Critically Endangered (CR), ten are Endangered (EN), 22 Vulnerable (VU), ten Near Threatened (NT), 15 Data Deficient (DD) and 105 Least Concern. Thus, 22% of the species for which a category was assigned other than DD were assessed as threatened (i.e. CR, EN or VU), as against 25% for mammals as a whole. Among otters, seven (58%) of the 12 species for which a category was assigned were identified as threatened. This reflects their attachment to rivers and other waterbodies, and heavy trade-driven hunting. The IUCN Red List species accounts are living documents to be updated annually, and further information to refine listings is welcome. Keywords: conservation status, Critically Endangered, Data Deficient, Endangered, Extinct, global threat listing, Least Concern, Near Threatened, Vulnerable Introduction dae (skunks and stink-badgers; 12), Mustelidae (weasels, martens, otters, badgers and allies; 59), Nandiniidae (African Palm-civet The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is the most authorita- Nandinia binotata; one), Prionodontidae ([Asian] linsangs; two), tive resource currently available on the conservation status of the Procyonidae (raccoons, coatis and allies; 14), and Viverridae (civ- world’s biodiversity. In recent years, the overall number of spe- ets, including oyans [= ‘African linsangs’]; 33). The data reported cies included on the IUCN Red List has grown rapidly, largely as on herein are freely and publicly available via the 2008 IUCN Red a result of ongoing global assessment initiatives that have helped List website (www.iucnredlist.org/mammals). -

Lack of Spatial Segregation in the Representation of Pheromones and Kairomones in the Mouse Medial Amygdala

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 11 August 2015 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00283 Lack of spatial segregation in the representation of pheromones and kairomones in the mouse medial amygdala Vinicius M. A. Carvalho 1, 2‡, Thiago S. Nakahara 1, 2‡, Leonardo M. Cardozo 1, 2 †, Edited by: Mateus A. A. Souza 1, 2, Antonio P. Camargo 1, 3, Guilherme Z. Trintinalia 1, 2, Eliana Ferraz 4 Markus Fendt, and Fabio Papes 1* Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg, Germany 1 Department of Genetics and Evolution, Institute of Biology, University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil, 2 Graduate Program in Reviewed by: Genetics and Molecular Biology, Institute of Biology, University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil, 3 Undergraduate Program in Qi Yuan, the Biological Sciences, Institute of Biology, University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil, 4 Campinas Municipal Zoo, Campinas, Memorial University, Canada Brazil Mario Engelmann, Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg, Germany The nervous system is organized to detect, internally represent and process sensory *Correspondence: information to generate appropriate behaviors. Despite the crucial importance of odors Fabio Papes, that elicit instinctive behaviors, such as pheromones and kairomones, their neural Department of Genetics and representation remains little characterized in the mammalian brain. Here we used Evolution, Institute of Biology, University of Campinas, expression of the immediate early gene product c-Fos as a marker of neuronal activity Rua Monteiro Lobato, 255, Campinas, to find that a wide range of pheromones and kairomones produces activation in the 13083-862 Sao Paulo, Brazil [email protected] medial nucleus of the amygdala, a brain area anatomically connected with the olfactory †Present Address: sensory organs. -

In the Mood Deer Have a Way of Advertising Their Wares and the Whereabouts– Scent, Sounds, and Body Language

A buck simulates reproductive response with flehman or lip curling to expose his vomeronasal organ to scent of a female’s urination. (frame from Quality Deer Management Assoc. video) In the Mood Deer have a way of advertising their wares and the whereabouts– scent, sounds, and body language J. Morton Galetto, CU Maurice River Last October I wrote an article about deer that included some aspects of their mating habits. It described mate guarding and the male deer or buck’s propensity to focus on following a female in estrus so as to insure he is the lucky suitor. During rut or the breeding season, when males spar competitively for reproductive rights over females, deer are on the move. The season begins in October and its height in our region is November 10- 20. Females that are not successfully fertilized will come into estrus a second time 28 days later, offering a second chance for them to produce young. All this moving around makes deer and drivers especially prone to road collisions. Bucks are particularly active during sunset and early morning. So slow down and stay alert. In last year’s story we offered lots of advice in this regard. White-tail deer are the local species here in Southern NJ. I thought it might be fun to talk about their indicators of lust – well, fun for me anyway. Deer employ three major methods of communications: scents, vocalizations, and body language. Deer are ungulates, meaning they are a mammal with a cloven hoof on each leg, split in two parts; you could describe them as toes or digits. -

Mammalian Pheromones – New Opportunities for Improved Predator Control in New Zealand

SCIENCE FOR CONSERVATION 330 Mammalian pheromones – new opportunities for improved predator control in New Zealand B. Kay Clapperton, Elaine C. Murphy and Hussam A. A. Razzaq Cover: Stoat in boulders in the Tasman River bed, Mackenzie Basin. Photo: John Dowding. Science for Conservation is a scientific monograph series presenting research funded by New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC). Manuscripts are internally and externally peer-reviewed; resulting publications are considered part of the formal international scientific literature. This report is available from the departmental website in pdf form. Titles are listed in our catalogue on the website, refer www.doc.govt.nz under Publications, then Series. © Copyright August 2017, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISSN 1177–9241 (web PDF) ISBN 978–1–98–851436–9 (web PDF) This report was prepared for publication by the Publishing Team; editing by Amanda Todd and layout by Lynette Clelland. Publication was approved by the Director, Threats Unit, Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. Published by Publishing Team, Department of Conservation, PO Box 10420, The Terrace, Wellington 6143, New Zealand. In the interest of forest conservation, we support paperless electronic publishing. CONTENTS Abstract 1 1. Introduction 2 1.1 The potential roles of pheromones in New Zealand predator control 2 1.2 Aim of this review 4 2. Pheromone identification and function in mammalian predator species 5 2.1 Mice 5 2.2 Rats 7 2.3 Rodent Major Urinary Proteins (MUPs) 9 2.4 Cats 10 2.5 Mustelids 11 2.6 Possums (with reference to other marsupials) 13 3. Odour perception and expression 14 3.1 How do animals perceive odours? 14 3.2 Influence of the MHC 16 4. -

Olfactory Communication in the Ferret (Mustela Furo L.) and Its Application in Wildlife Management

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. OLFACTORY COMMUNICATION IN THE FERRET (MUSTELA FURO L.) AND ITS APPLICATION IN WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT A Thesis Prepared in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Zoology at Massey University Barbara Kay Clapperton 1985 �;·.;L��:"·;�� �is Copyrigj;lt Fonn Title:·J.;:E,:£j;esis: O\fgc:..�O("j CoW\I"'h.JA"lC,citQC\ � �� '�'Jd" � (�tJ.o.kgL.) � -\� C\�ic..Q;"er.. \h wA�·�. (1) ta.W-:> I give permission for my thesis to be rrede a���;�d�� .. -; ':: readers in the Massey University Library under conditi¥?� . C • determined by the Librarian. ; �dO n�t�sh my..,):hesi�o be�de�ai�e � _ _ re er/l.thout""my wmtten c6nse� for _ -<-L_ nths. ' ... ' � (2 ) �l.--.::�;. I � t � thej>'is, ov& c0er. rrej0Se s� ¥ I :.. an �r n�t ' ut ¥1h undef'condrtion srdeterdU.n6§. � t e rarl. I do not wish my thesis, or a copy, to be sent to another institution without my written consent for 12 nonths. (3 ) I agree that my thesis rrey be copied for Library use.: . �� ... Signed �,t. .... : B K Clappe n ;" Date (� �v � ; .. \, The cct1m�t of this thesis belongs to the author. Readers must sign t��::�arre in the space below to show that they recognise this. lmy· · are asked to add their perm:ment address.