JANET SCOTT HOYT, PIANO and NORMAN NELSON, VIOLIN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

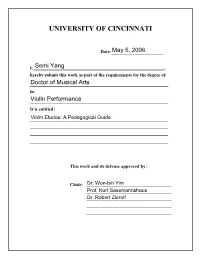

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ VIOLIN ETUDES: A PEDAGOGICAL GUIDE A document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2006 by Semi Yang [email protected] B.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1995 M.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1999 Advisor: Dr. Won-bin Yim Reader: Prof. Kurt Sassmannshaus Reader: Dr. Robert Zierolf ABSTRACT Studying etudes is one of the most essential parts of learning a specific instrument. A violinist without a strong technical background meets many obstacles performing standard violin literature. This document provides detailed guidelines on how to practice selected etudes effectively from a pedagogical perspective, rather than a historical or analytical view. The criteria for selecting the individual etudes are for the goal of accomplishing certain technical aspects and how widely they are used in teaching; this is based partly on my experience and background. The body of the document is in three parts. The first consists of definitions, historical background, and introduces different of kinds of etudes. The second part describes etudes for strengthening technical aspects of violin playing with etudes by Rodolphe Kreutzer, Pierre Rode, and Jakob Dont. The third part explores concert etudes by Wieniawski and Paganini. -

Dissertation FINAL 5 22

ABSTRACT Title: BEETHOVEN’S VIOLINISTS: THE INFLUENCE OF CLEMENT, VIOTTI, AND THE FRENCH SCHOOL ON BEETHOVEN’S VIOLIN COMPOSITIONS Jamie M Chimchirian, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2016 Dissertation directed by: Dr. James Stern Department of Music Over the course of his career, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) admired and befriended many violin virtuosos. In addition to being renowned performers, many of these virtuosos were prolific composers in their own right. Through their own compositions, interpretive style and new technical contributions, they inspired some of Beethoven’s most beloved violin works. This dissertation places a selection of Beethoven’s violin compositions in historical and stylistic context through an examination of related compositions by Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755–1824), Pierre Rode (1774–1830) and Franz Clement (1780–1842). The works of these violin virtuosos have been presented along with those of Beethoven in a three-part recital series designed to reveal the compositional, technical and artistic influences of each virtuoso. Viotti’s Violin Concerto No. 2 in E major and Rode’s Violin Concerto No. 10 in B minor serve as examples from the French violin concerto genre, and demonstrate compositional and stylistic idioms that affected Beethoven’s own compositions. Through their official dedications, Beethoven’s last two violin sonatas, the Op. 47, or Kreutzer, in A major, dedicated to Rodolphe Kreutzer, and Op. 96 in G major, dedicated to Pierre Rode, show the composer’s reverence for these great artistic personalities. Beethoven originally dedicated his Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61, to Franz Clement. This work displays striking similarities to Clement’s own Violin Concerto in D major, which suggests that the two men had a close working relationship and great respect for one another. -

New 6-Page Template a 27/4/16 9:32 PM Page 1

573000bk Kummer:New 6-page template A 27/4/16 9:32 PM Page 1 Frédéric Kummer (1797–1879) und François Schubert (1808–1878) zu den bekanntesten Bühnenwerken des Opern- und führt im pianissimo wieder nach G-dur und zum Dreivier- Duos Concertants pour Violon et Violoncelle Ballettkomponisten Louis Joseph Ferdinand Hérold teltakt zurück – zunächst als ruhiges Moderato molto mit (1791–1833) und zu den beliebtesten Singspielen des 19. der Melodie im Violoncello, dann als abschließendes Friedrich August (alias Frédéric) Kummer wurde am 5. Unterricht bei seinem Vater und bei Antonio Rolla (1798- Jahrhunderts gehörte. Das Duo in der Tonart D-dur beginnt Allegro molto. August 1797 in Meiningen geboren. Sein Vater Friedrich 1837) wurde er in Paris von Charles Philippe Lafont (1781- mit einem Allegro, das neben einigen lieblichen Momenten Die Deux Duos de Concert pour Violon et Violoncelle August sen. (1770-1849) war zunächst Oboist in der 1839) ausgebildet, der seinerseits bei Rodolphe Kreutzer viel virtuoses Passagenwerk enthält. Von hier aus führt der op. 52 schließlich beginnen mit einem Souvenir de Fra Hofkapelle des Herzogs von Sachsen-Meiningen, und Pierre Rode studiert hatte. Da man ihn bisweilen mit Weg zu einem Andantino mit zwei Variationen, denen sich Diavolo, der wohl besten opéra-comique des Autorenteams übersiedelte aber mit seiner Familie bald nach der Geburt dem weitaus berühmteren Franz Schubert aus Wien ein Melancolico in Moll und im Dreivierteltakt anschließt. Daniel-François-Esprit Auber (1782–1871) und Eugène seines Sohnes nach Dresden und gab seinem Sprössling verwechselte, nahm er in Paris, wo er unter anderem mit Danach werden die ursprüngliche Tonart und der Scribe (1791–1861), dessen Namen wir üblicherweise im Frédéric den ersten Musikunterricht, bevor dieser von Justus Chopin Freundschaft schloss, den Namen »François« an. -

Henry Thoreau, from Which He Would Obtain Plutarch Materials Plus Quotes from Crates of Thebes and Simonides’S “Epigram on Anacreon” That He Would Recycle in a WEEK.)

HDT WHAT? INDEX 1814 1814 EVENTS OF 1813 General Events of 1814 SPRING JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH SUMMER APRIL MAY JUNE FALL JULY AUGUST SEPTEMBER WINTER OCTOBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER Following the death of Jesus Christ there was a period of readjustment that lasted for approximately one million years. –Kurt Vonnegut, THE SIRENS OF TITAN THE NEW-ENGLAND ALMANACK FOR 1814. By Isaac Bickerstaff. Providence, Rhode Island: John Carter. THE NEW-ENGLAND ALMANACK FOR 1814. By Isaac Bickerstaff. Providence: John Carter. Sold also by George Wanton, Newport. 21-year-old Edward Hitchcock calculated and published a COUNTRY ALMANAC (recalculated and reissued each year to 1818). John Farmer’s “A Sketch of Amherst, New Hampshire” (2 COLL. MASS. HIST. SOC. II. BOSTON). Noah Webster, Esq. became a member of the Massachusetts General Court (he would serve also in 1815 and 1817). Carl Phillip Gottfried von Clausewitz was reinstated in the Prussian army. EVENTS OF 1815 HDT WHAT? INDEX 1814 1814 The 2d of 3 volumes of a revised critical edition of an old warhorse, ANTHOLOGIA GRAECA AD FIDEM CODICIS OLIM PALATINI NUNC PARISINI EX APOGRAPHO GOTHANO EDITA ..., prepared by Christian Friedrich Wilhelm Jacobs, appeared in Leipzig (the initial volume had appeared in 1813 and the final volume would appear in 1817). ANTHOLOGIA GRAECA (My working assumption, for which I have no evidence, is that this is likely to have been the unknown edition consulted by Henry Thoreau, from which he would obtain Plutarch materials plus quotes from Crates of Thebes and Simonides’s “Epigram -

The Fifteenth-Anniversary Season: the Glorious Violin July 14–August 5, 2017 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the Soothing Melody STAY with US

The Fifteenth-Anniversary Season: The Glorious Violin July 14–August 5, 2017 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the soothing melody STAY WITH US Spacious modern comfortable rooms, complimentary Wi-Fi, 24-hour room service, itness room and a large pool. Just two miles from Stanford. BOOK EVENT MEETING SPACE FOR 10 TO 700 GUESTS. CALL TO BOOK YOUR STAY TODAY: 650-857-0787 CABANAPALOALTO.COM DINE IN STYLE 4290 Bistro features creative dishes from our Executive Chef and Culinary Team. Our food is a fusion of Asian Flavors using French techniques while sourcing local ingredients. TRY OUR CHAMPAGNE SUNDAY BRUNCH RESERVATIONS: 650-628-0145 4290 EL CAMINO REAL PALO ALTO CALIFORNIA 94306 Music@Menlo The Glorious Violin the fifteenth-anniversary season July 14–August 5, 2017 DAVID FINCKEL AND WU HAN, ARTISTIC DIRECTORS Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 The Glorious Violin Program Overview 6 Essay: “Violinists: Old Time vs. Modern” by Henry Roth 10 Encounters I–V 13 Concert Programs I–VII Léon-Ernest Drivier (1878–1951). La joie de vivre, 1937. Trocadero, Paris, France. Photo credit: Archive 41 Carte Blanche Concerts I–V Timothy McCarthy/Art Resource, NY 60 Chamber Music Institute 62 Prelude Performances 69 Koret Young Performers Concerts 72 Master Classes 73 Café Conversations 74 The Visual Arts at Music@Menlo 75 Music@Menlo LIVE 76 2017–2018 Winter Series 78 Artist and Faculty Biographies 90 Internship Program 92 Glossary 96 Join Music@Menlo 98 Acknowledgments 103 Ticket and Performance Information 105 Map and Directions 106 Calendar www.musicatmenlo.org 1 2017 Season Dedication Music@Menlo’s ifteenth season is dedicated to the following individuals and organizations that share the festival’s vision and whose tremendous support continues to make the realization of Music@Menlo’s mission possible. -

The French School of Violin Playing Between Revolution and Reaction: a Comparison of the Treatises of 1803 and 1834 by Pierre Baillot

Nineteenth-Century Music Review, page 1 of 30 © Cambridge University Press 2020 doi:10.1017/S147940981900034X The French School of Violin Playing between Revolution and Reaction: A Comparison of the Treatises of 1803 and 1834 by Pierre Baillot Douglas Macnicol The Australian National University [email protected] Pierre Baillot (1771–1842) was a central figure in the development of the early nineteenth-century French School of violin playing. This school was itself the source of the twentieth-century Russian and American schools, and all the great players of the modern era can trace their lineage back to Baillot and his colleagues. The French School was the first to systematize violin teaching within an institutional framework with normative aspirations. Its history is bound up with that of the Paris Conservatoire, established in 1795. Work by French scholars of the Conservatoire and its teaching has tended to assert a continuity of ideals and aesthetics across time, even an essential Frenchness, and work by English-language scholars has been more concerned with the influence of the School on developments in playing styles and composition than on the evolution of attitudes to music teaching. This analysis of the language of the two founding pedagogical texts reveals a contested cultural landscape, and explores how a revolutionary institution with lofty principles could be overtaken by cultural change in a few short decades. It finishes by questioning the tradi- tional elision of the French and Franco-Belgian schools, and suggests that Brussels, rather than constituting a mere branch of the Paris school, rescued it from premature irrelevance. -

Training Creative Violinists: Taking a Page from Baillot's L'art Du Violon

Training Creative Violinists: Taking a Page from Baillot’s L’Art Du Violon Anna McMichael A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia 2018 1 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work.’ Signed …………………………………………….............. Date ……… 3 May, 2018 2 Abstract This thesis analyses Pierre Marie Franҫois de Sales Baillot’s L’Art du Violon (1834). My argument is that the ideas in his treatise, although written in the mid-nineteenth century, are again relevant in training tertiary violin students to become cultured, creative and adaptable musicians. Classical musicians today face considerable challenges in attracting and inspiring their audiences. While maintaining classical music traditions, musicians and arts organisations therefore are experimenting with new forms of delivery: broader themes and genres, multi-media performances, and new technologies. Performers today must draw upon considerable knowledge and skills in order to appeal to audiences, whether in concert halls or in listening to recorded music. -

The Franco-Belgian Violin School: Pedagogy, Principles, and Comparison with the German and Russian Violin Schools, from the Eighteenth Through Twentieth Centuries

The Franco-Belgian Violin School: Pedagogy, Principles, and Comparison with the German and Russian Violin Schools, from the Eighteenth through Twentieth Centuries A document submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music Violin 2019 by Gyu Hyun Han B.A., Korean National University of Arts, Korea, 2005 M.M., Korean National University of Arts, Korea, 2007 Committee Chair: Kurt Sassmannshaus, MM Abstract The Franco-Belgian violin school, famed for its elegance, detailed tone, polished sound, and variety of bow strokes, dominated violin performance at the turn of the twentieth century. Yet despite this popularity, and the continuing influence of the school as reflected in the standard violin repertoire, many violinists today do not know what constitutes the Franco-Belgian violin style. Partly, this is due to a lack of contextual information; while many scholars have written about the history of the violin and violin playing techniques, there is currently very little literature comparing the principles and performance characters of specific violin schools. This study therefore introduces the principles and techniques of the Franco-Belgian violin school, presented in comparison with those of the German and Russian violin schools; these features are catalogued and demonstrated both through examinations of each school’s treatises and analyses of video recordings by well-known violinists from each school. ii iii Table of Contents Abstract ii List of Tables vi List if Figures vi List of Musical Examples vii I. -

Listening in Paris: a Cultural History, by James H

Listening in Paris STUDIES ON THE HISTbRY OF SOCIETY AND CULTURE Victoria E. Bonnell and Lynn Hunt, Editors 1. Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution, by Lynn Hunt 2. The People ofParis: An Essay in Popular Culture in the Eighteenth Century, by Daniel Roche 3. Pont-St-Pierre, 1398-1789: Lordship, Community, and Capitalism in Early Modern France, by Jonathan Dewald 4. The Wedding of the Dead: Ritual, Poetics, and Popular Culture in Transylvania, by Gail Kligman 5. Students, Professors, and the State in Tsarist Russia, by Samuel D. Kass ow 6. The New Cultural History, edited by Lynn Hunt 7. Art Nouveau in Fin-de-Siecle France: Politics, Psychology, and Style, by Debora L. Silverman 8. Histories ofa Plague Year: The Social and the Imaginary in Baroque Florence, by Giulia Calvi 9. Culture ofthe Future: The Proletkult Movement in Revolutionary Russia, by Lynn Mally 10. Bread and Authority in Russia, 1914-1921, by Lars T. Lih 11. Territories ofGrace: Cultural Change in the Seventeenth-Century Diocese of Grenoble, by Keith P. Luria 12. Publishing and Cultural Politics in Revolutionary Paris, 1789-1810, by Carla Hesse 13. Limited Livelihoods: Gender and Class in Nineteenth-Century England, by Sonya 0. Rose 14. Moral Communities: The Culture of Class Relations in the Russian Printing Industry, 1867-1907, by Mark Steinberg 15. Bolshevik Festivals, 1917-1920, by James von Geldern 16. 'l&nice's Hidden Enemies: Italian Heretics in a Renaissance City, by John Martin 17. Wondrous in His Saints: Counter-Reformation Propaganda in Bavaria, by Philip M. Soergel 18. Private Lives and Public Affairs: The Causes Celebres ofPre Revolutionary France, by Sarah Maza 19. -

Rodolphe Kreutzer

Rodolphe Kreutzer Violin Concertos 1, 6 & 7 Laurent Albrecht Breuninger Südwestdeutsches Kammerorchester Pforzheim Timo Handschuh Rodolphe Kreutzer Rodolphe Kreutzer (1766–1831) Violin Concerto No. 6 in E minor [KWV 28] 29'17 1 Allegro maestoso 20'22 2 Sicilienne 4'18 3 Rondeau 4'37 Mit freundlicher Unterstützung von Violin Concerto No. 7 in A major [KWV 34] 19'08 4 Maestoso 11'36 5 Adagio 2'41 6 Rondo. Allegretto 4'50 Violin Concerto No. 1 in G major [KWV 13] 23'42 7 Allegro moderato 14'39 All rights of the producer and of the owner of the work reserved. Unauthorized copying, hiring, renting, public performance and broadcasting 8 Pastorale 3'31 of this record prohibited. 9 Rondeau 5'31 cpo 555 206–2 Co-Production: cpo/SWR T.T.: 63'25 Recording: July 10–12, 2014, Ev. Matthäuskirche Pforzheim Recording Producer & Digital Editing: Gabriele Starke Recording Engineer: Angela Öztanil Laurent Albrecht Breuninger, Violin Mastering: Caroline Rebstock Südwestdeutsches Kammerorchester Pforzheim Publisher: Ries & Erler, Berlin Executive Producers: Burkhard Schmilgun/Dr. Kerstin Unseld Timo Handschuh Cover Painting: Georges Stein, »Auf der Place de la Concorde bei Regen« Christie’s Images Ltd © Photo: Artothek, 2019; Design: Lothar Bruweleit cpo, Lübecker Str. 9, D–49124 Georgsmarienhütte ℗ 2019 – Made in Germany Rodolphe Kreutzer, ist erst aus französischen Quellen verbürgt) sein Glück des einstigen Mannheimer Hofkapellmeisters Johann Violinkonzerte Nr. 6, 7 & 1 in der Fremde suchte und als Klarinettist bei den in Ver- Stamitz, der sich 1770 in Paris bzw. Versailles nieder- sailles zum Schutz des Königs stationierten Schweizer- gelassen hatte und in den Concerts spirituels als Solist Zu Beginn der 1760er Jahre entschloss sich ein aus gut- garden anheuerte. -

Annales Historiques De La Révolution Française

Annales historiques de la Révolution française 379 | janvier-mars 2015 Nouvelles perspectives pour l'histoire de la musique (1770-1830) Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ahrf/13406 DOI : 10.4000/ahrf.13406 ISSN : 1952-403X Éditeur : Armand Colin, Société des études robespierristes Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 février 2015 ISBN : 978-2-200-92958-9 ISSN : 0003-4436 Référence électronique Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 379 | janvier-mars 2015, « Nouvelles perspectives pour l'histoire de la musique (1770-1830) » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 15 février 2018, consulté le 01 juillet 2021. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ahrf/13406 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ahrf.13406 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 1 juillet 2021. Tous droits réservés 1 SOMMAIRE Revisiter l’histoire sociale et politique de la musique années 1770 – années 1830 Mélanie Traversier Articles La musique des spectacles en Suède, 1770 – 1810 : opéra-comique français et politique de l’appropriation Charlotta Wolff Le rendez-vous manqué entre Mozart et l’aristocratie parisienne (1778) David Hennebelle Dynamiques de professionnalisation et jeux de protection : pratiques et enjeux de l’examen des maîtres de chapelle à Rome (1784) Élodie Oriol Trois batailles pour la République dans les concerts parisiens (1789-1794) : Ivry, Jemappes et Fleurus Joann Élart Les fantômes de l’Opéra ou les abandons du Directoire Philippe Bourdin Des fêtes anniversaires royales aux fêtes nationales ? Pratique musicale et politique -

MIECZYSŁAW KARŁOWICZ's VIOLIN CONCERTO in a MAJOR, OP. 8: HISTORY, STYLE and PERFORMANCE ASPECTS by MAŁGORZATA MARIA STASZE

MIECZYSŁAW KARŁOWICZ’S VIOLIN CONCERTO IN A MAJOR, OP. 8: HISTORY, STYLE AND PERFORMANCE ASPECTS by MAŁGORZATA MARIA STASZEWSKA (Under the Direction of Stephen Valdez and Levon Ambartsumian) ABSTRACT The Polish violin concerto literature includes a fine concerto that is rarely performed outside of Poland: Mieczysław Karłowicz’s (1876-1909) Violin Concerto in A major, Op. 8, written in 1902. Today the concerto is widely played in Poland, but it still has not earned a strong reputation abroad. The possible reasons for its lack of popularity are the short life of the composer, which gave him little time to promote the piece, and his conflict with the Polish musical establishment, which banned performances of his music. The literature regarding the piece is limited, especially in English. Occasional reviews/articles or CD liner notes mention its excellent idiomatic violin writing, but this issue is not discussed in detail. The lack of worldwide publications of the part, the rare recordings by international performers, and the absence of scholarly analyses on the performance aspects of the piece contribute to its obscurity. The goal of this study is to promote the piece by presenting its values: a skillfully outlined form, idiomatic violin writing, expressive musical content, and the combination of both virtuosic technique and musical interest. Chapter one provides a sketch of the historical background of the Polish violin concerto’s evolution, followed by Karłowicz’s biographical information and work style description focusing on his Violin Concerto. Chapter two is a formal analysis of the piece illustrated by analytical charts and musical examples. Chapter three discusses the technical and editorial violin issues, phrasing, and sound production problems related to its performance.