Robin Stowell Henryk Wieniawski: »The True Successor« of Nicolò Paganini? a Comparative Assessment of the Two Virtuosos with Particular Reference to Their Caprices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

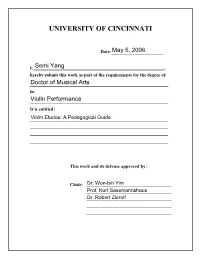

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ VIOLIN ETUDES: A PEDAGOGICAL GUIDE A document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2006 by Semi Yang [email protected] B.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1995 M.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1999 Advisor: Dr. Won-bin Yim Reader: Prof. Kurt Sassmannshaus Reader: Dr. Robert Zierolf ABSTRACT Studying etudes is one of the most essential parts of learning a specific instrument. A violinist without a strong technical background meets many obstacles performing standard violin literature. This document provides detailed guidelines on how to practice selected etudes effectively from a pedagogical perspective, rather than a historical or analytical view. The criteria for selecting the individual etudes are for the goal of accomplishing certain technical aspects and how widely they are used in teaching; this is based partly on my experience and background. The body of the document is in three parts. The first consists of definitions, historical background, and introduces different of kinds of etudes. The second part describes etudes for strengthening technical aspects of violin playing with etudes by Rodolphe Kreutzer, Pierre Rode, and Jakob Dont. The third part explores concert etudes by Wieniawski and Paganini. -

From the Violin Studio of Sergiu Schwartz

CoNSERVATORY oF Music presents The Violin Studio of Sergiu Schwartz SPOTLIGHT ON YOUNG VIOLIN VIRTUOSI with Tao Lin, piano Saturday, April 3, 2004 7:30p.m. Amamick-Goldstein Concert Hall de Hoernle International Center Program Polonaise No. 1 in D Major ..................................................... Henryk Wieniawski Gabrielle Fink, junior (United States) (1835 - 1880) Tambourin Chino is ...................................................................... Fritz Kreisler Anne Chicheportiche, professional studies (France) (1875- 1962) La Campanella ............................................................................ Niccolo Paganini Andrei Bacu, senior (Romania) (1782-1840) (edited Fritz Kreisler) Romanza Andaluza ....... .. ............... .. ......................................... Pablo de Sarasate Marcoantonio Real-d' Arbelles, sophomore (United States) (1844-1908) 1 Dance of the Goblins .................................................................... Antonio Bazzini Marta Murvai, senior (Romania) (1818- 1897) Caprice Viennois ... .... ........................................................................ Fritz Kreisler Danut Muresan, senior (Romania) (1875- 1962) Finale from Violin Concerto No. 1 in g minor, Op. 26 ......................... Max Bruch Gareth Johnson, sophomore (United States) (1838- 1920) INTERMISSION 1Ko<F11m'1-za from Violin Concerto No. 2 in d minor .................... Henryk Wieniawski ten a Ilieva, freshman (Bulgaria) (1835- 1880) llegro a Ia Zingara from Violin Concerto No. 2 in d minor -

Rachel Barton Violin Patrick Sinozich, Piano DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 041 INSTRUMENT of the DEVIL 1 Saint-Saëns: Danse Macabre, Op

Cedille Records CDR 90000 041 Rachel Barton violin Patrick Sinozich, piano DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 041 INSTRUMENT OF THE DEVIL 1 Saint-Saëns: Danse Macabre, Op. 40 (7:07) Tartini: Sonata in G minor, “The Devil’s Trill”* (15:57) 2 I. Larghetto Affectuoso (5:16) 3 II. Tempo guisto della Scuola Tartinista (5:12) 4 III. Sogni dellautore: Andante (5:25) 5 Liszt/Milstein: Mephisto Waltz (7:21) 6 Bazzini: Round of the Goblins, Op. 25 (5:05) 7 Berlioz/Barton-Sinozich: Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath from Symphonie Fantastique, Op. 14 (10:51) 8 De Falla/Kochanski: Dance of Terror from El Amor Brujo (2:11) 9 Ernst: Grand Caprice on Schubert’s Der Erlkönig, Op. 26 (4:11) 10 Paganini: The Witches, Op. 8 (10:02) 1 1 Stravinsky: The Devil’s Dance from L’Histoire du Soldat (trio version)** (1:21) 12 Sarasate: Faust Fantasy (13:30) Rachel Barton, violin Patrick Sinozich, piano *David Schrader, harpsichord; John Mark Rozendaal, cello **with John Bruce Yeh, clarinet TT: (78:30) Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation, a not-for-profit foun- dation devoted to promoting the finest musicians and ensembles in the Chicago area. The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation’s activities are supported in part by grants from the WPWR-TV Chan- nel 50 Foundation and the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. Zig and zig and zig, Death in cadence Knocking on a tomb with his heel, Death at midnight plays a dance tune Zig and zig and zig, on his violin. -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6

Concert Program V: Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6 Friday, August 5 F RANZ JOSEph HAYDN (1732–1809) 8:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School Rondo all’ongarese (Gypsy Rondo) from Piano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 (1795) S Jon Kimura Parker, piano; Elmar Oliveira, violin; David Finckel, cello Saturday, August 6 8:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton HErmaNN SchULENBURG (1886–1959) AM Puszta-Märchen (Gypsy Romance and Czardas) (1936) PROgram OVERVIEW CharlES ROBERT VALDEZ A lifelong fascination with popular music of all kinds—espe- Serenade du Tzigane (Gypsy Serenade) cially the Gypsy folk music that Hungarian refugees brought to Germany in the 1840s—resulted in some of Brahms’s most ANONYMOUS cap tivating works. The music Brahms composed alla zinga- The Canary rese—in the Gypsy style—constitutes a vital dimension of his Wu Han, piano; Paul Neubauer, viola creative identity. Concert Program V surrounds Brahms’s lusty Hungarian Dances with other examples of compos- JOHANNES BrahmS (1833–1897) PROGR ERT ers drawing from Eastern European folk idioms, including Selected Hungarian Dances, WoO 1, Book 1 (1868–1869) C Hungarian Dance no. 1 in g minor; Hungarian Dance no. 6 in D-flat Major; the famous rondo “in the Gypsy style” from Joseph Haydn’s Hungarian Dance no. 5 in f-sharp minor G Major Piano Trio; the Slavonic Dances of Brahms’s pro- Wu Han, Jon Kimura Parker, piano ON tégé Antonín Dvorˇák; and Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane, a paean C to the Hun garian violin virtuoso Jelly d’Arányi. -

Violin Repertoire List

Violin Repertoire List In reverse order of difficulty (beginner books at top). Please send suggestions / additions to [email protected]. Version 1.1, updated 27 Aug 2015 List A: (Pieces in 1st position & basic notation) Fiddle Time Starters Fiddle Time Joggers Fiddle Time Runners Fiddle Time Sprinters The ABCs of Violin Musicland Violin Books Musicland Lollipop Man (Violin Duets) Abracadabra - Book 1 Suzuki Book 1 ABRSM Grade Book 1 VIolinSchool Editions: Popular Tunes in First Position ● Twinkle Twinkle Little Star ● London Bridge is Falling Down ● Frère Jacques ● When the Saints Go Marching In ● Happy Birthday to You ● What Shall We Do With the Drunken Sailor ● Ode to Joy ● Largo from The New World ● Long Long Ago ● Old MacDonald Had a Farm ● Pop! Goes the Weasel ● Row Row Row Your Boat ● Greensleeves ● The Irish Washerwoman ● Yankee Doodle Stanley Fletcher, New Tunes for Strings, Book 1 2 Step by Step Violin Play Violin Today String Builder Violin Book One (Samuel Applebaum) A Tune a Day I Can Read Music Easy Classical Violin Solos Violin for Dummies The Essential String Method (Sheila Nelson) Robert Pracht, Album of Easy Pieces, Op. 12 Doflein, Violin Method, Book 1 Waggon Wheels Superstudies (Mary Cohen) The Classical Experience Suzuki Book 2 Stanley Fletcher, New Tunes for Strings, Book 2 Doflein, Violin Method, Book 2 Alfred Moffat, Old Masters for Young Players D. Kabalevsky, Album Pieces for 1 and 2 Violins and Piano *************************************** List B: (Pieces in multiple positions and varieties of bow strokes) Level 1: Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor Johann Sebastian Bach: Air on the G string Bach Gavotte in D (Suzuki Book 3) Bach Gavotte in G minor (Suzuki Book 3) Béla Bartók: 44 Duos for two violins Karl Bohm www.ViolinSchool.org | [email protected] | +44 (0) 20 3051 0080 3 Perpetual Motion Frédéric Chopin Nocturne in C sharp minor (arranged) Charles Dancla 12 Easy Fantasies, Op.86 Antonín Dvořák Humoresque King Henry VIII Pastime with Good Company (ABRSM, Grade 3) Fritz Kreisler: Berceuse Romantique, Op. -

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED the CRITICAL RECEPTION of INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY in EUROPE, C. 1815 A

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Zarko Cvejic August 2011 © 2011 Zarko Cvejic THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 Zarko Cvejic, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 The purpose of this dissertation is to offer a novel reading of the steady decline that instrumental virtuosity underwent in its critical reception between c. 1815 and c. 1850, represented here by a selection of the most influential music periodicals edited in Europe at that time. In contemporary philosophy, the same period saw, on the one hand, the reconceptualization of music (especially of instrumental music) from ―pleasant nonsense‖ (Sulzer) and a merely ―agreeable art‖ (Kant) into the ―most romantic of the arts‖ (E. T. A. Hoffmann), a radically disembodied, aesthetically autonomous, and transcendent art and on the other, the growing suspicion about the tenability of the free subject of the Enlightenment. This dissertation‘s main claim is that those three developments did not merely coincide but, rather, that the changes in the aesthetics of music and the philosophy of subjectivity around 1800 made a deep impact on the contemporary critical reception of instrumental virtuosity. More precisely, it seems that instrumental virtuosity was increasingly regarded with suspicion because it was deemed incompatible with, and even threatening to, the new philosophic conception of music and via it, to the increasingly beleaguered notion of subjective freedom that music thus reconceived was meant to symbolize. -

Dissertation Summary of Three Recitals, with Works Derived from Folk Influences, Living American Composers and Works Containing a Theme and Variations

Dissertation Summary of Three Recitals, with Works Derived from Folk Influences, Living American Composers and Works Containing a Theme and Variations. by Heewon Uhm A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Professor David Halen, Chair Professor Anthony D. Elliott Professor Freda A. Herseth Professor Andrew W. Jennings Assisant Professor Youngju Ryu Heewon Uhm [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-8334-7912 © Heewon Uhm 2019 DEDICATION To God For His endless love To my dearest teacher, David Halen For inviting me to the beautiful music world with full of inspiration To my parents and sister, Chang-Sub Uhm, Sunghee Chun, and Jungwon Uhm For trusting my musical journey ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii LIST OF EXAMPLES iv ABSTRACT v RECITAL 1 1 Recital 1 Program 1 Recital 1 Program Notes 2 RECITAL 2 9 Recital 2 Program 9 Recital 2 Program Notes 10 RECITAL 3 18 Recital 3 Program 18 Recital 3 Program Notes 19 BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 iii LIST OF EXAMPLES EXAMPLE Ex-1 Semachi Rhythm 15 Ex-2 Gutgeori Rhythm 15 Ex-3 Honzanori-1, the transformed version of Semachi and Gutgeori rhythm 15 iv ABSTRACT In lieu of a written dissertation, three violin recitals were presented. Recital 1: Theme and Variations Monday, November 5, 2018, 8:00 PM, Stamps Auditorium, Walgreen Drama Center, University of Michigan. Assisted by Joonghun Cho, piano; Hsiu-Jung Hou, piano; Narae Joo, piano. Program: Olivier Messiaen, Thème et Variations; Johann Sebastian Bach, Ciaconna from Partita No. -

Dissertation FINAL 5 22

ABSTRACT Title: BEETHOVEN’S VIOLINISTS: THE INFLUENCE OF CLEMENT, VIOTTI, AND THE FRENCH SCHOOL ON BEETHOVEN’S VIOLIN COMPOSITIONS Jamie M Chimchirian, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2016 Dissertation directed by: Dr. James Stern Department of Music Over the course of his career, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) admired and befriended many violin virtuosos. In addition to being renowned performers, many of these virtuosos were prolific composers in their own right. Through their own compositions, interpretive style and new technical contributions, they inspired some of Beethoven’s most beloved violin works. This dissertation places a selection of Beethoven’s violin compositions in historical and stylistic context through an examination of related compositions by Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755–1824), Pierre Rode (1774–1830) and Franz Clement (1780–1842). The works of these violin virtuosos have been presented along with those of Beethoven in a three-part recital series designed to reveal the compositional, technical and artistic influences of each virtuoso. Viotti’s Violin Concerto No. 2 in E major and Rode’s Violin Concerto No. 10 in B minor serve as examples from the French violin concerto genre, and demonstrate compositional and stylistic idioms that affected Beethoven’s own compositions. Through their official dedications, Beethoven’s last two violin sonatas, the Op. 47, or Kreutzer, in A major, dedicated to Rodolphe Kreutzer, and Op. 96 in G major, dedicated to Pierre Rode, show the composer’s reverence for these great artistic personalities. Beethoven originally dedicated his Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61, to Franz Clement. This work displays striking similarities to Clement’s own Violin Concerto in D major, which suggests that the two men had a close working relationship and great respect for one another. -

BAZZINI Complete Opera Transcriptions

95674 BAZZINI Complete Opera Transcriptions Anca Vasile Caraman violin · Alessandro Trebeschi piano Antonio Bazzini 1818-1897 CD1 65’09 CD4 61’30 CD5 53’40 Bellini 4. Fantaisie de Concert Mazzucato and Verdi Weber and Pacini Transcriptions et Paraphrases Op.17 (Il pirata) Op.27 15’08 1. Fantaisie sur plusieurs thêmes Transcriptions et Paraphrases Op.17 1. No.1 – Casta Diva (Norma) 7’59 de l’opéra de Mazzucato 1. No.5 – Act 2 Finale of 2. No.6 – Quartet CD3 58’41 (Esmeralda) Op.8 15’01 Oberon by Weber 7’20 from I Puritani 10’23 Donizetti 2. Fantasia (La traviata) Op.50 15’55 1. Fantaisie dramatique sur 3. Souvenir d’Attila 16’15 Tre fantasie sopra motivi della Saffo 3. Adagio, Variazione e Finale l’air final de 4. Fantasia su temi tratti da di Pacini sopra un tema di Bellini Lucia di Lammeroor Op.10 13’46 I Masnadieri 14’16 2. No.1 11’34 (I Capuleti e Montecchi) 16’30 3. No.2 14’59 4. Souvenir de Transcriptions et Paraphrases Op.17 4. No.3 19’43 Beatrice di Tenda Op.11 16’11 2. No.2 – Variations brillantes 5. Fantaisia Op.40 (La straniera) 14’02 sur plusieurs motifs (La figlia del reggimento) 9’44 CD2 65’16 3. No.3 – Scène et romance Bellini (Lucrezia Borgia) 11’05 Anca Vasile Caraman violin · Alessandro Trebeschi piano 1. Variations brillantes et Finale 4. No.4 – Fantaisie sur la romance (La sonnambula) Op.3 15’37 et un choeur (La favorita) 9’02 2. -

An Ashgate Book

An Ashgate Book ZZZURXWOHGJHFRP Ernst by Frederick Tatham, England, 1844 (from a picture once owned by W.E. Hill and Sons) HEINRICH WILHELM ERNST: VIRTUOSO VIOLINIST To Marie Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst: Virtuoso Violinist M.W. ROWE Birkbeck College, University of London, UK ROUTLEDGE Routledge Taylor & Francis Group LONDON AND NEW YORK First published 2008 by Ashgate Publishing Published 2016 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © M.W. Rowe 2008 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. M.W. Rowe has asserted his moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Rowe, Mark W. Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst : virtuoso violinist 1. Ernst, Heinrich Wilhelm, 1812–1865 2. Violinists – Biography I. Title 787.2'092 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rowe, Mark W. Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst : virtuoso violinist / by Mark W. Rowe. p. cm. Includes discography (p. 291), bibliographical references (p. 297), and index. ISBN 978-0-7546-6340-9 (alk. paper) 1. -

Download Booklet

572291bk Women EU 30/7/10 12:57 Page 4 Clare Howick Clare Howick has established herself as one of the leading violinists of her BRITISH WOMEN generation. She has a special interest in twentieth-century British violin repertoire which has resulted in a number of premières and recordings. Her début disc, Sonata Lirica and Other Works by Cyril Scott was Editor’s Choice in COMPOSERS Gramophone magazine. A second disc of Cyril Scott’s violin sonatas was subsequently recorded for Naxos (8.572290). She has performed most of the violin concerto repertoire with various orchestras including the Philharmonia Smyth • Maconchy • Poldowski Orchestra, has appeared at major festivals in Britain, including the Cheltenham International Festival, and has broadcast on BBC Radio 3. She combines solo and chamber performances with appearing as guest leader of many orchestras, Tate • Barns including the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra, BBC National Orchestra of Wales, Ulster Orchestra and the Orchestra of English National Opera. She Clare Howick, Violin • Sophia Rahman, Piano gratefully acknowledges the loan of a Stradivarius violin (1721) for this recording. Photograph: Guy Mayer Sophia Rahman Sophia Rahman has recorded over twenty chamber discs for companies including Naxos, ASV, Dutton/Epoch, Meridian, Linn Records, and Guild, among others. Her career encompasses solo, chamber and coaching activities. She acts as an official accompanist for the Lionel Tertis International Viola Competition, the Barbirolli International Oboe Competition and IMS/Prussia Cove. She has given master-classes in China at the Conservatory of Music in Xi An and the Xing Hai Conservatory of Music in Guangzhou, in Russia at the Modest Mussorgsky College in St Petersburg, in Sweden at Lilla Akadamien, Stockholm, and at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama.