Dissertation Summary of Three Recitals, with Works Derived from Folk Influences, Living American Composers and Works Containing a Theme and Variations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STAR V41,11 November-12-1948.Pdf (6.573Mb)

Violinist Roman Totenberg To Present Third Artist Series Concert Violinist Roman Totenberg, Polish- · the Moscow Opera concert master - stem. L r.-, and now an American citizen , and was soon making tours of Russia, Returning to the United States in wil! perform for the next Artists' , as a child prodigy. When only fifteen, 1938, Mr. Totenberg came to stay. Series concert in the college chapel Mr. Totenberg made his debut in He received his American citizenship ar 8:00 p. m., Friday, November 19. Poland as soloist with the Warsaw five years later. 'Ih: s internationally-known artist was Philharmonic Symphony orchestra. He has appeared as soloist with the acclaimed by the New York PM as I Further studies were made unded New York Philliarinonic, the Cleve- follows: "One of the finest of the Carl Flesch in Berlin and Gorges land Symphony, the National Sym- younger group of violinists, he is a Enesco in Paris. Following this, he phony, and tile New York City Cen- profoundly sincere and sound musician toured all the major capitals of ter orchestras. His recitals have been ond in his performances never allows Europe, including London, Berlin. heard in the White House and at mere virtuosity to overshadow the i The Hague, and Rome. Carnegie Hall. .. us: c itself." After his first American tour in ' In his coming performance, Mr. Coming from an artistic family, 1935, he returned to Europe where Totenberg will play compositions Mr. Totenberg first showed interest , he played with Szymanowski, famous from French, Bruch, Bartok, Nin, in the violin at the age of six. -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6

Concert Program V: Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6 Friday, August 5 F RANZ JOSEph HAYDN (1732–1809) 8:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School Rondo all’ongarese (Gypsy Rondo) from Piano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 (1795) S Jon Kimura Parker, piano; Elmar Oliveira, violin; David Finckel, cello Saturday, August 6 8:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton HErmaNN SchULENBURG (1886–1959) AM Puszta-Märchen (Gypsy Romance and Czardas) (1936) PROgram OVERVIEW CharlES ROBERT VALDEZ A lifelong fascination with popular music of all kinds—espe- Serenade du Tzigane (Gypsy Serenade) cially the Gypsy folk music that Hungarian refugees brought to Germany in the 1840s—resulted in some of Brahms’s most ANONYMOUS cap tivating works. The music Brahms composed alla zinga- The Canary rese—in the Gypsy style—constitutes a vital dimension of his Wu Han, piano; Paul Neubauer, viola creative identity. Concert Program V surrounds Brahms’s lusty Hungarian Dances with other examples of compos- JOHANNES BrahmS (1833–1897) PROGR ERT ers drawing from Eastern European folk idioms, including Selected Hungarian Dances, WoO 1, Book 1 (1868–1869) C Hungarian Dance no. 1 in g minor; Hungarian Dance no. 6 in D-flat Major; the famous rondo “in the Gypsy style” from Joseph Haydn’s Hungarian Dance no. 5 in f-sharp minor G Major Piano Trio; the Slavonic Dances of Brahms’s pro- Wu Han, Jon Kimura Parker, piano ON tégé Antonín Dvorˇák; and Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane, a paean C to the Hun garian violin virtuoso Jelly d’Arányi. -

Download Booklet

572291bk Women EU 30/7/10 12:57 Page 4 Clare Howick Clare Howick has established herself as one of the leading violinists of her BRITISH WOMEN generation. She has a special interest in twentieth-century British violin repertoire which has resulted in a number of premières and recordings. Her début disc, Sonata Lirica and Other Works by Cyril Scott was Editor’s Choice in COMPOSERS Gramophone magazine. A second disc of Cyril Scott’s violin sonatas was subsequently recorded for Naxos (8.572290). She has performed most of the violin concerto repertoire with various orchestras including the Philharmonia Smyth • Maconchy • Poldowski Orchestra, has appeared at major festivals in Britain, including the Cheltenham International Festival, and has broadcast on BBC Radio 3. She combines solo and chamber performances with appearing as guest leader of many orchestras, Tate • Barns including the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra, BBC National Orchestra of Wales, Ulster Orchestra and the Orchestra of English National Opera. She Clare Howick, Violin • Sophia Rahman, Piano gratefully acknowledges the loan of a Stradivarius violin (1721) for this recording. Photograph: Guy Mayer Sophia Rahman Sophia Rahman has recorded over twenty chamber discs for companies including Naxos, ASV, Dutton/Epoch, Meridian, Linn Records, and Guild, among others. Her career encompasses solo, chamber and coaching activities. She acts as an official accompanist for the Lionel Tertis International Viola Competition, the Barbirolli International Oboe Competition and IMS/Prussia Cove. She has given master-classes in China at the Conservatory of Music in Xi An and the Xing Hai Conservatory of Music in Guangzhou, in Russia at the Modest Mussorgsky College in St Petersburg, in Sweden at Lilla Akadamien, Stockholm, and at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama. -

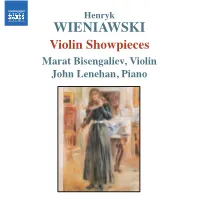

Wieniawski EU 2/26/08 2:01 PM Page 5

550744 bk Wieniawski EU 2/26/08 2:01 PM Page 5 Henryk Wienlawski (1835-1880) seinem Lehrer Massart gewidmet und eine glänzende nieder. Er schickte ein Telegramm an Isobels Mutter, in Kompositionen für Violine und Klavier Studie über den berühmten italienischen Tanz. dem er sie für das nächste Konzert einlud, das am Henryk Die Polonaisen, die Mazurka und der Kujawiak nächsten Tag stattfinden sollte. Auch Vater Hampton Henryk Wieniawski wurde am 10. Juni 1835 als Sohn befremdenden Streichquartette von Ludwig van zeigen Wieniawski als Meister im Umgang mit den kam, und nachdem er die Legende gehört und die des Militärarztes Tadeusz Wieniawski in Lublin Beethoven. polnischen Nationaltänzen, wohingegen die “Legende“ Reaktion seiner Tochter darauf beobachtet hatte, gab er WIENIAWSKI geboren. Seine Mutter Regina war die Tochter des Der Komponist Wieniawski hat naheliegenderweise in eine ganz andere Richtung weist. Sie ist das Zeugnis dem Paar seinen Segen. Henryk und Isobel heirateten angesehenen polnischen Pianisten Edward Wolff. wie viele seiner Kollegen sein eigenes Instrument in den seiner Liebe zu Isobel Hampton, die er zunächst nach und hatten fünf Kinder. Offenbar erkannten die Eltern früh die musikalische Mittelpunkt seiner Arbeit gestellt. Die beiden dem Willen ihres Vaters nicht heiraten sollte. Nachdem Begabung ihres Sohnes, und sie konnten es sich leisten, Violinkonzerte bilden einen Höhepunkt seines der Familienvorstand ihn in London hatte “abblitzen“ Keith Anderson Violin Showpieces ihn in die besten pädagogischen Hände zu geben: Sein Werkkatalogs; dazu kommen kammermusikalische lassen, zog sich Wieniawski zurück, um einige Stunden erster Lehrer war ein Schüler von Louis Spohr gewesen, Stücke für Violine und Klavier sowie Unterrichts- und Geige zu spielen - danach schrieb er die “Legende“ Deutsche Fassung: Cris Posslac der zweite unterrichtete unter anderem auch Joseph Anschauungsmaterial. -

The Darius Milhaud Society Centennial Celebration Performance Calendar, 1993 - 1994

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Darius Milhaud Society Newsletters Michael Schwartz Library 1993 The Darius Milhaud Society Centennial Celebration Performance Calendar, 1993 - 1994 Darius Milhaud Society Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/milhaud_newsletters Part of the History Commons, and the Music Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Darius Milhaud Society, "The Darius Milhaud Society Centennial Celebration Performance Calendar, 1993 - 1994" (1993). Darius Milhaud Society Newsletters. 9. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/milhaud_newsletters/9 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Michael Schwartz Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Darius Milhaud Society Newsletters by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DARIUS MILHAUD CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION PERFORMANCE CALENDAR, Second Issue and DARIUS MILHAUD PERFORMANCE CALENDAR fo r the 1993 -1994 SEASON and SUMMER 1994 The information in this Darius Milhaud Centen11i al Ce /ebratio11 Perfo rm a 11 ce Ca l enda r is new and therefore different from the performances listed in the first Centennial 1ssue. Included here are performances for wllich information was received after press time for that first issue (May 1992). If this new infonnation was included in the 1992 or 1993 Newsletters, page refere11ces are given rather than repeating the information. A few listings here include information that was incomplete or previously unavailable in previous listings or where changes later occurred. DMCCP C refers to the first issue of the D a riu s Milhaud Centennial Cel e bration P erfo rmance Calendar. -

Classic Choices April 6 - 12

CLASSIC CHOICES APRIL 6 - 12 PLAY DATE : Sun, 04/12/2020 6:07 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto No. 3 6:15 AM Georg Christoph Wagenseil Concerto for Harp, Two Violins and Cello 6:31 AM Guillaume de Machaut De toutes flours (Of all flowers) 6:39 AM Jean-Philippe Rameau Gavotte and 6 Doubles 6:47 AM Ludwig Van Beethoven Consecration of the House Overture 7:07 AM Louis-Nicolas Clerambault Trio Sonata 7:18 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento for Winds 7:31 AM John Hebden Concerto No. 2 7:40 AM Jan Vaclav Vorisek Sonata quasi una fantasia 8:07 AM Alessandro Marcello Oboe Concerto 8:19 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 70 8:38 AM Darius Milhaud Carnaval D'Aix Op 83b 9:11 AM Richard Strauss Der Rosenkavalier: Concert Suite 9:34 AM Max Reger Flute Serenade 9:55 AM Harold Arlen Last Night When We Were Young 10:08 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Exsultate, Jubilate (Motet) 10:25 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 3 10:35 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 10 (for two pianos) 11:02 AM Johannes Brahms Symphony No. 4 11:47 AM William Lawes Fantasia Suite No. 2 12:08 PM John Ireland Rhapsody 12:17 PM Heitor Villa-Lobos Amazonas (Symphonic Poem) 12:30 PM Allen Vizzutti Celebration 12:41 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Traumbild I, symphonic poem 12:55 PM Nino Rota Romeo & Juliet and La Strada Love 12:59 PM Max Bruch Symphony No. 1 1:29 PM Pr. Louis Ferdinand of Prussia Octet 2:08 PM Muzio Clementi Symphony No. -

Roman Totenberg Dies At

FACULTY OBITUARIES CFA Professor Roman Totenberg Emeritus Roman Totenberg (left) Dies at 101 and violin stu- dent Daniel Han Violinist, beloved CFA (CFA’98,’00,’02). professor, classical music legend By Susan Seligson !"#$ %&'# ()*+,) his death on May 8, 101-year-old Roman Totenberg lay in bed at his Newton, Mass., home, listening to a student play the Brahms violin concerto. “Slow down,” he told her, according to a blog entry by S. I. FRED SWAY Rosenbaum on the Boston Phoenix website. Suffering kidney failure, his “You learn a lot more than the stu- birthday with a concert by the Boston voice just a whisper, the famed violinist dents do.” University Symphony Orchestra. spent his final hours doing what he He received BU’s Metcalf Cup and Totenberg attended the concert loved most: teaching. Prize, the University’s top teaching with family, friends, and former Born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1911, honor, in 1996, and was named Artist students, many of whom are among Totenberg, a College of Fine Arts Teacher of the Year in 1981 by the today’s leading concert artists, School of Music professor emeritus, American String Teachers Association. including Wang, Na Sun, a violinist had been a constant and inspiring “A survivor of two world wars, with the New York Philharmonic, presence in classical music over the Roman Totenberg offered the world and Ikuko Mizuno (CFA’69), a Bos- past century, having worked closely hope and love through his extraordi- ton Symphony Orchestra violinist. with many well-known composers, nary music-making,” says Benjamín Proceeds from the concert benefited including Samuel Barber, Igor Juárez, dean of the College of Fine the Roman and Melanie Totenberg Stravinsky, Aaron Copland, Paul Arts. -

Corey Cerovsek, Violin & Katja Cerovsek, Piano

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 2-20-1999 Concert: Corey Cerovsek, violin & Katja Cerovsek, piano Corey Cerovsek Katja Cerovsek Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons ITHACA COLLEGE CONCERTS 1998-99 COREY CEROVSEK, violin KA TJA CEROVSEK, piano Polonaise No. 1 in D Major, op. 4 Henryk Wieniawski (1835-1880) Sonata in C minor, op. 30, no. 2 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Allegro con brio Adagio cantabile Scherzo: Allegro Finale: Allegro-Presto Sonata No. 3 in G minor Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Allegro vivo Intermede-fantasque et Zeger Finale-tres anime INTERMISSION Sonata No. 1 in G Major, op. 78 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Vivace ma non troppo Adagio Allegro molto moderato Tzigane Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Saturday, February 20, 1999 Ford Hall Auditorium 8:15 p.m. DELOS RECORDS "/, Exclusive Management: ARTS MANAGEMENT GROUP, INC., 150 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10011 Public Relations/Publicity: M. L. FALCONE, Public Relations West 68th Street, Suite 1114 New York, NY 10023 PROGRAM NOTES Henryk Wieniawski ( 1835-1880). Polonaise No. 1 in D for Violin and Piano, op. 4 The son of the talented pianist Regina Wolff-Wieniawska, Henryk Wieniawski began his violin studies with Jan Hornziel and Stanislaw Serwaczynski (1791-1859), Joachim's first teacher. At the urging of her brother, the concert pianist Edouard Wolff, Henryk's mother took him to Paris where he was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire in 1843 and studied violin with Lambert-Joseph Massart (1811-92), Fritz Kreisler's teacher. -

Program Notes | Joshua Bell and Cristi

23 Season 2017-2018 Saturday, February 17, The Philadelphia Orchestra at 8:00 Cristian Măcelaru Conductor Joshua Bell Violin Beethoven Leonore Overture No. 3, Op. 72b Wieniawski Violin Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 22 I. Allegro moderato II. Romance: Andante non troppo III. Allegro con fuoco—Allegro moderato (à la Zingara) Intermission Dvořák Symphony No. 8 in G major, Op. 88 I. Allegro con brio II. Adagio—Poco più animato—Tempo I. Meno mosso III. Allegretto grazioso—Coda: Molto vivace IV. Allegro ma non troppo This program runs approximately 1 hour, 45 minutes. The February 17 concert is sponsored by Judith Broudy. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 25 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and impact through Research. is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues The Orchestra’s award- orchestras in the world, to discover new and winning Collaborative renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture Learning programs engage sound, desired for its its relationship with its over 50,000 students, keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home families, and community hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, members through programs audiences, and admired for and also with those who such as PlayINs, side-by- a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area sides, PopUP concerts, innovation on and off the performances at the Mann free Neighborhood concert stage. -

557981 Bk Szymanowski EU

570723 bk Szymanowski EU:570723 bk Szymanowski EU 12/15/08 5:13 PM Page 16 Karol Also available: SZYMANOWSKI Harnasie (Ballet-Pantomime) Mandragora • Prince Potemkin, Incidental Music to Act V Ochman • Pinderak • Marciniec Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir • Antoni Wit 8.557981 8.570721 8.570723 16 570723 bk Szymanowski EU:570723 bk Szymanowski EU 12/15/08 5:13 PM Page 2 Karol SZYMANOWSKI Also available: (1882-1937) Harnasie, Op. 55 35:47 Text: Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937) and Jerzy Mieczysław Rytard (1899-1970) Obraz I: Na hali (Tableau I: In the mountain pasture) 1 No. 1: Redyk (Driving the sheep) 5:09 2 No. 2: Scena mimiczna (zaloty) (Mimed Scene (Courtship)) 2:15 3 No. 3: Marsz zbójnicki (The Tatra Robbers’ March)* 1:43 4 No. 4: Scena mimiczna (Harna i Dziewczyna) (Mimed Scene (The Harna and the Girl))† 3:43 5 No. 5: Taniec zbójnicki – Finał (The Tatra Robbers’ Dance – Finale)† 4:42 Obraz II: W karczmie (Tableau II: In the inn) 6 No. 6a: Wesele (The Wedding) 2:36 7 No. 6b: Cepiny (Entry of the Bride) 1:56 8 No. 6c: Pie siuhajów (Drinking Song) 1:19 9 No. 7: Taniec góralski (The Tatra Highlanders’ Dance)* 4:20 0 No. 8: Napad harnasiów – Taniec (Raid of the Harnasie – Dance) 5:25 ! No. 9: Epilog (Epilogue)*† 2:39 Mandragora, Op. 43 27:04 8.557748 Text: Ryszard Bolesławski (1889-1937) and Leon Schiller (1887-1954) @ Scene 1**†† 10:38 # Scene 2†† 6:16 $ Scene 3** 10:10 % Knia Patiomkin (Prince Potemkin), Incidental Music to Act V, Op. -

Applied Music Faculty Bios Bozena Jedrzejczak Brown - Piano

Applied Music Faculty Bios Bozena Jedrzejczak Brown - Piano Ms. Brown holds a Masters degree in Harpsichord Performance (2000) from The Peabody Institute, in the studio of Webb Wiggins. She also studied harpsichord at Northern Illinois University, earning an Individualized Masters degree (1998), and received a BM in Music Theory (1991) from The Frederic Chopin University of Music in Warsaw, Poland. She is a piano instructor at Garrison Forest School’s Music and Arts Department, and teaches harpsichord and figured bass at The Baltimore School for the Arts. Ms. Jedrzejczak Brown free-lances as a basso continuo player on harpsichord and chamber organ, and has performed with many groups in the Mid-Atlantic region, including Washington Cornett and Sackbut Ensemble, Orchestra of the 17th Century, Richmond Symphony Orchestra, Mid-Atlantic Symphony, Bach Concert Series Orchestra, and others. Hanchien Lee - Piano Since her debut with the Philadelphia Orchestra at age sixteen, pianist Hanchien Lee has performed throughout the US, in Europe, and across her native Taiwan. She has delighted audiences at Steinway Hall in New York, Phillips Collection in Washington DC, the Basilica San Pietro in Italy, and the National Concert Hall in Taipei, Taiwan. As a concerto soloist, she has appeared with diverse ensembles such as the Taiwan National Orchestra, Capella Cracoviensis in Poland, the Plainfield Symphony in New Jersey, and the Chamber Orchestra of Perugia, Italy. Among her many awards are top prizes in the Heida Hermanns and Wonderlic Piano Competitions as well as the prestigious ChiMei Scholarship in Taiwan. Ms. Lee earned the Doctor of Musical Arts degree from the Peabody Conservatory, the Master of Music degree and Artist Diploma from Yale University, and the Bachelor of Music degree from the Curtis Institute of Music, where she was admitted at age 11.